31 minute read

Education

news is both parents and educators can take basic steps to help boost confidence in learning to help middle-school kids at home and at school.

With confidence such a key component of learning success, how can parents and educators keep levels high so that students not only succeed at learning, but also find joy in it? The key is hands-on learning. A whopping 97 percent of teachers in the U.S. say that handson learning builds confidence among their students, though that doesn’t have to be limited to the classroom. Here are simple ways to help middle-schoolers gain confidence in themselves and their education:

Advertisement

Hands-on learning at home

Adults who incorporate hands-on learning can make a big impact, with 87 percent of students reporting that when they learn via hands-on projects, they tend to remember the topics for longer. At home, invite kids into the kitchen to cook together, talking about measurements and reactions of cooking ingredients before enjoying a meal as a family. Another idea: Have them help out as you use tools to work on your car, discussing the problem, brainstorming the potential solutions and fixing it together.

Hands-on learning at school

When projects come to life, kids can learn through collaboration and exploration, which can help improve processing and retention. The new LEGO Education SPIKE Prime, bringing together familiar LEGO bricks with digital programming, lets students learn essential 21st-century skills through a hands-on approach. The kit includes guides for 32 different creations, though the possibilities are limitless. “We believe deeply in the value of hands-on learning experiences to build curiosity and confidence, spur development, bring more joy to learning and spark imagination - and that’s exactly what SPIKE Prime offers,” said Esben Stark Jurgensen, President of LEGO Education.

Ask questions through open discussion

Having open, engaging and nonjudgmental conversations with middle-school kids is important to breaking down barriers. Let them lead the conversation, but if it stalls out, take the lead by asking questions about how they think and feel. Remember, no answer or thought is a bad one. It’s also important, as an adult, to show vulnerability. If you can show you’re OK being comfortable with success or failure, it helps them gain confidence that it’s OK to feel that way, too.

To learn more about confidence-building, educational opportunities and LEGO Education SPIKE Prime, visit LEGOeducation.com/ SPIKEprime. Esben Stærk JØrgensen, President of LEGO Education.

EDUCATION BAAM

Building AfricAn AmericAn minds

Effective youth programs represent an important need for the social and educational aspect of the young African American in our world. Enhancing and building the minds of African American youth is a high level priority of many individuals in the Talbot County area in Maryland. As the country faces the difficult question of how to reach the youth, these individuals have taken on the task in the mid shore of the Eastern Shore of Maryland and have succeeded in answering the difficult question.

Building African American Minds (BAAM) formed in 2005 is a group designed and developed by a couple who wanted to answer the question of aiding the African American youth in the Talbot County area. The call for the scholarships resulted in no application which motivated the couple to dig further for the quest to answer the difficult question. The couple then refocused their energy to the middle school level and because of this great shift many have gone to college off of the support of the organization.

BAAM helped these youth to develop into aspiring college students and created a sense of pride and thirst for knowledge. For many of the students that matriculated through the program, BAAM served as a support system in and outside of school. Mr. & Mrs. Derick and Dina Daly developed the program to help students prosper in their quest for knowledge as well as their development in social and behavior skills. BAAM’s longevity of over 14 years is recognized as a pillar in the area of support for youth in the community. Many students have reached back from their days in the BAAM program to assist and aid the youth of today to be successful and achieve great success in their lives. The beauty of this program is that It focuses on the positive of one’s life and how a child can use motivation to enhance their possibilities of success.

BAAM uses different strategies to raise funds to assist the youth. One particular event is the Annual BAAM Festival that draws large crowds of well into the hundreds. The Fest celebrated with 23 partners

who BAAM has collaborated with in helping African American males become productive, confident citizens through positive academic, social, emotional, and spiritual experiences as children and young men. BAAM is joined in support for this event by over 20 businesses and organizations to awareness for the vision and mission of the program. Information booths, musical entertainment, giveaways, dance contest and basketball tournaments. This event is 5 years into its progress and has grown each year in size and productivity.

BAAM has been recognized by the State of Maryland and the State House of Delegates for its work in assisting youth in the community. In 2018, BAAM received the Governor’s citation for the efforts to identify African American males who are at risk of failure in school and for recognizing and addressing the socio-economic barriers that may inhibit their ability to learn effectively, providing enrichment in a safe, caring and better structured environment by partnering with local faith-based organizations, parents and concerned citizens with similar agendas and clearly stated goals.

Left: Mr. & Mrs. Derick and Dina Daly pictured with Governor Hogan; Below: face painting and craft activities; Below Right: Working in the garden. Top: BAAM Athletic Center dedication; Left: Athletic Center under construction; Below: members playing foosball.

INTEGRATION

in hindsight

Ruby

Bridges was only six years old when she became the face of what is seen today as a never ending battle of desegregation, years after the passing of Brown vs Education. In 1954, the supreme court ruled that state laws regulating racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. Several years after that decision, states and local districts were resisting. Much like in New Orle-

ans, Louisiana with little Ruby, it wasn’t until the 1960’s eastern shore public schools took a break at resisting and began to integrate their public schools. 15 years after Brown vs Education, Somerset and Dorchester County de-segregated. Activists like Ruby Bridges have paved the way towards equal education. The question remains, did black Americans benefit from integration at all?

In 1988, resistance to Brown vs Education peaked in the south. The percentage of black students in majority white schools went from zero to 43.5%. However, recent reports from UCLA Civil Rights Project, in 2016 showed a decreased. The percentage of black students in majority white schools is just below where it was in 1968, 23.2%. With continuous lack of oversight from courts, parents, educators, and activists like Ruby Bridges, are still fighting for equal education on many levels. In 2016, Maryland was found to be among the most segregated states for black students.

Lower shore public schools were relatively late to desegregate. In Cambridge, Maces Lane, Dorchester County’s only Black High School was closed. It followed the closing of Somerset Jr. Sr. High, in Princess Anne, MD and shortly after Carter G. Woodson High, an all- black school in Crisfield, MD. Schools

were closed and qualified teachers lost jobs. A popular thought is that eastern shore black students suffered greatly from integration and

Life plans for African American students in Sussex County were indefinite until the opening of the William C. Jason Comprehensive High School in 1950.

The late Mr. H. Fletcher Brown, a philanthropist of Wilmington, Delaware, who died in 1944 left $250,000 in his will toward the construction of a downstate African American High School. Legislature provided for the construction of a Comprehensive High School and meet the needs of students of all levels and varying interest to include, vocational, commercial, general, and college prepatory courses.

The name of Charles Jason, a minister and educator approved by the State Board of Education. Dr. Jason was a minister and teacher for several years in the public school system of Delaware. He was the first black president of Delaware State College.

The school opened for classes October 2, 1950, including grades nine through twelve. In 1953, with expansion, junior high students (seventh and eighth grades), were enrolled. The William C. Jason Comprehensive High School ceased to exist after June 30,1967.

continued on pg 23 William C. Jason Comprehensive High School

Northampton High School

Tidewater’s Institute doors closed in 1935. The community became concerned about educational opportunities for African American youth and the concern of transportation was a priority. Mrs. Margaret McCune, a Jeanes Teacher’s supervisor made a vow: “if you open the doors of the Northampton County High, we’ll see that the children get there!”

Consequently, public education began for the African American youth in the fall of 1935 in the Old Tidewater building at Chesapeake, also known as Cobbs Station. Then the School Board moved the school to its building located in Machipongo, VA and in the fall of 1940 moved the high school into the building. In 1952 a high school for African American students was approved. Constructed in 1953, the county’s first purpose-built African American high school was built, Northampton County High School. The students moved in the building in September 1953 and Mr. William H. Smith was the Principal.

Northampton County High School remained a high school until the Spring of 1970 and subsequently was closed in 2008

continued from pg 22 it shows. It was a poorly planned and failed strategy. In 2017, Wicomico County school board settled with the U.S. Justice Department aimed at disciplining practices against minorities and disabled children. The district admitted no fault.

Years after little Ruby walked passed that woman who hung a noose around a black baby doll’s neck, activists and parents are attempting to correct the wrongs made in a failed strategy towards equal education. In the Wicomico County settlement, the board agreed to train staff and revise the code of conduct. The community and school officials, however, aren’t in agreeance if they have fulfilled their agreement to the U.S. Justice Department. The Civil Rights Data Collection gathered detailed information from over 96,000 public schools for the 2015-2016 school year. It proved black and hispanic male students get harsher discipline than their white counterparts.

Lower eastern shore students welcomed integration and many appreciated the opportunity it gave athletes and scholars. However, it was apparent that lack of proper implementation shifted the school climate and their communities as a whole. The unrest was inevitable as the resistance to integration was strong. With “Deliberate Speed” federal officials ordered Wicomico County in 1964, to integrate. Many of those pioneers are alive today to tell their story. Memories hold vividly the image of unfair treatment of teachers and administrators

towards black students. Cultural competence is vital for any school to thrive. In present day, activists are calling for specialized training for educators in valuing diversity and being culturally self-aware.

Racial segregation have been ultimately outlawed for over 65 years, however many reports find that today’s students are in racially concentrated districts but also divided by income. There has been an overwhelming proof of evidence of double segregation by race and class, yet there have been few positive initiatives. Advocates for equal education have found that school segregation concentrates black students in high poverty schools, which tend to have lower achievement, fewer resources, and behavioral issues. Though the link between the two is apparent, there is little research measuring economic segregation among schools. Largely due to the focus of race in Brown vs Education.

The Equal Justice Initiative recently published an article that confirms nine million American children are attending racially and economically segregated schools. Fighting for equal education did not stop at Brown vs Education. In the Milliken vs Bradley case, black parents filed a desegregation suit against Detroit Public School System, alleging the school district was racially segregated and that the school district lines were dividing majority black Detroit from its nearly all white neighborhoods. Ultimately reinforcing residential segregation. In that case it was found that that schools were segregated and but also govern-

In 1931, J. Edgar Thomas, Susie Wharton Thomas, and William H. Bailey sold a lot in the town of Accomack containing 0.842 of an acre to the trustees of the Accomack County Colored High School Association for $750.00. The trustees, Reverend R. C. Hughes, W. J. Laws, R. H. Hall, G.W. Downing, Mary N. Smith, C.H. Ewell, and Alma Parker, purchased the property and in 1932

built the first secondary school for black children. This school was named for Mary Nottingham Smith (1892-1951), a trustee of the school and well known on the Eastern Shore. Born in Northampton County, Smith worked in the Accomack County school system since 1921 as a Jeanes Educational Supervisor.

The Jeanes Foundation (also known as the Negro Rural School Fund) was founded by a Quaker, Anna T. Jeanes, to improve vocational training programs for teachers of black students. In 1953, a larger high school, also named Mary Nottingham Smith, was built. The old High School became T.C. Walker Elementary School, named after an African-American attorney from Gloucester County. This building was demolished in 1987.

continued on pg 25 Mary N. Smith High School T.C. Walker Elementary

Worcester County High School

In December 1948, Superintendent Paul D. Cooper proposed a building campaign that included a new high school for African Americans in Newark. Plans for Worcester County’s new African American high school began in August 1950. The design included a 52,000 square foot school with 28 classrooms, a cafeteria, and a separate auditorium. The site se-

lected for the African American school was a 168-acre farm on the east side of Worcester Highway south of Newark and the campus included a model farm.

African American students were bused from the three areas of the county to begin classes at Worcester County High School in September 1953. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court passed the case Brown v. Board of Education and on June 7, 1955, it was announced that Worcester County would not adhere to the Supreme Court decision. Worcester county would be the first in Maryland to officially defy the Court’s decision.

Students in Worcester County did not experience any desegregation until September 1964, when seventh grade student Larry Waples transferred into Stephen Decatur High School in Berlin. ment officials, private organizations, such as loaning institutions and real estate associations were reactivating residential segregation.

It is not widely known that Brown vs Education was argued again a year later. The NAACP urged desegregation to move forward, however it was clear that in 1954, there was no set plan on how or how quickly desegregation was going to be achieved. On May 31, 1955, the Supreme Court sided with the states that had segregated schools and washed their hands of follow through and returned the responsibility to state courts to figure out the process. Ultimately that decision is why little Ruby was six when she became the face of ongoing battle and why lower eastern shore public schools were relatively late to desegregate. Did integration help or hurt Black America? It’s hard to tell because in hindsight, we haven’t truly achieved full integration in our American schools. America has yet to see the full fruit of its labor and parents, educators, and activists are still fighting for equal education.

Salisbury High School

In 1902 the first industrial school for African-Americans opened the Salisbury Colored Grammar School. By 1907, the space was outgrown and the school moved to a warehouse on Commerce Street. In 1915, the school’s name was changed to Colored Industrial High School, and Charles H. Chipman was hired as the school administrator. The school was expanded to a four year industrial high school and its first graduation exercises were held at the Colored Industrial High School in 1919. The school was later renamed Salisbury High School, under the direction of its African-American principal, Charles Chipman, who served 46 years as principal, until he retired in 1961.

A new school opened in the fall of 1930, but continued overcrowding led to the construction of eight additional classrooms in 1936. In 1950, the African-American community petitioned the Board for a larger school. The request was approved and the Salisbury High School opened in 1954. It continued to operate until the early 1960s when Wicomico County began its desegregation process. Carter G. Woodson School

Prior to 1908, there was only one educational facility in Crisfield: the original Crisfield Academy. In 1908, the very first Crisfield High School was built, succeeding the Academy. This school, only served the white population and was closed in 1926 when a new, larger building was constructed. A school was built for the African Americans, named Crisfield Colored High School, which was only equipped for teaching up to sixth grade. Eventually, this school would be renamed Carter G. Woodson High School. By the 1969-1970 school year Crisfield was desegregated, and Woodson High School became the area middle school.

Somerset Jr. Sr. High School

Opening in late winter of 1954 and closing in 1969, Somerset Jr-Sr High School was the home of the dragons. The students of Somerset Jr. Sr High School met in the building that is known today as Kiah Hall. Kiah Hall at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore houses classes for students in the Business and Technology department. Kiah Hall was remembered for its 15 years as a segregated public school. The school serviced African American students living in the northern part of Somerset county until 1969.

Mace’s Lane High School

The history of Mace’s Lane began in the late 1940s when W. T. Boston was our superintendent. Mr. Boston, Charles Cornish (County Commissioner) and the Board of Education selected the original site for Mace’s Lane which became Dorchester County’s only African American High School. Construction finally began on June 15, 1951. The first graduating class, whose motto was “Prepare today for leadership tomorrow” walked down the aisles of the school in June 1953. The history of Mace’s Lane High School played an integral part in the design of the current middle school which opened in January 2004. Today, Mace’s Lane Middle School continues to carry the proud tradition from 1953 of preparing our students for a variety of leadership opportunities as our original motto stated. Robert Russa Moton Jr. Sr. High School

Conditions of the Port Street School were not equal to the white schools and the State Educational Survey Commission reported that the Port Street School now Easton Colored School was one of the poorest buildings in the state. Following delays, construction began in 1918 and the new building dedicated on February 21, 1919.

On November 21, 1937, the Easton Colored School was renamed and dedicated in honor of Robert Russa Moton. “ Ole Moton ‘ now consisted of five buildings on Port Street and one on Higgins. The gymnasium was located on Higgins Street behind the Asbury M. E. Church.

The Robert Russa Moton Junior/Senior High School on Glenwood Avenue opened in 1953. This school was dedicated on Sunday, November 15, 1953. After the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, Talbot County gave black students “free-choice” to attend formerly allwhite schools. But few did and Moton continued to operate as an all-black school until 1967 when the Talbot County system was fully integrated.

Kennard High School

Lucretia Kennard came to the Eastern Shore from Philadelphia in 1903.

A forward-thinking educator, Kennard distinguished herself within a segregated system that was most definitely not structured in her favor. As a supervisor, Lucretia Kennard was responsible for recruiting teachers and developing curriculum but her highest ambition was to open a high school for black students. Lucretia Kennard Daniels died three years before the school that would carry both her name and academic tradition opened its doors in 1936.

Queen Anne’s County was one of the leading counties in Maryland to achieve integration. Many in the community attributed the successful transition to the efforts of Rhodes, as he personally met with all communities about the implementation of integration. 1966 was the last year smaller segregated high schools in Queen Anne’s County Public Schools existed. Under the leadership of Queen Anne’s County Superintendent of Schools, the late Dr. Harry Rhodes, of Queenstown, segregation ended in 1966. The very next year, Queen Anne’s County High School was opened to all high school students in the county. Lockerman High School

June 10th, 1930, Sir Isaac Thomas gave six acres of land in north Denton as a site for the new black high school. Lockerman High School, named after Joseph Harrison Lockerman graduated from Morgan State University in 1886. At a recent reunion, several people interviewed said that in the school’s early days, parents paid for a privately owned bus, whose owner, Walter Mosley, would drive their children to school.

Beginning in 1956 the Caroline County Board of Education had announced that county schools were open to all students on a freedom of choice. However desegregation was very slow. Beginning with the 1964-65 school year, some white teachers were assigned to all-black schools, and in 1965-66, seven black teachers were on faculties of desegregated schools.

April 1965, designated by the Board of Education as a period for application for transfer. Its desegregation plan was accepted by the U.S. Office of Education on June 18, 1965. In 1966, North Caroline High School opened in Ridgely, the Lockerman High School became a middle school.

Henry Highland Garnet High School

In 1916, the original Garnet Elementary School opened on College Avenue in Chestertown, across from Bethel A.M.E. Church. It became Henry Highland Garnet High School in 1923. In 1950, a new building was constructed across the street, next to Bethel Church, and was Kent County’s only African American high school until 1967, when all schools were integrated. Garnet then became an integrated elementary school while both black and white students attended Chestertown High School.

Legendary Garnet principal Elmer T. Hawkins set the tone for education in the black community. Hawkins, a graduate of Morgan State College, served as Garnet’s principal for 41 of the 44 years that the building served as the high school for Kent County’s African-American students. After integration in 1967, he served as the principal of the integrated Chestertown Middle School until his death in 1973. George Washington Carver High School

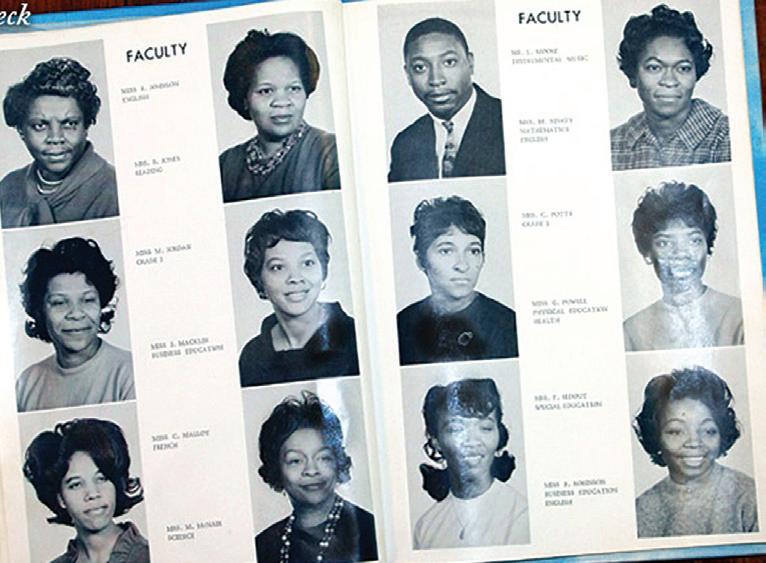

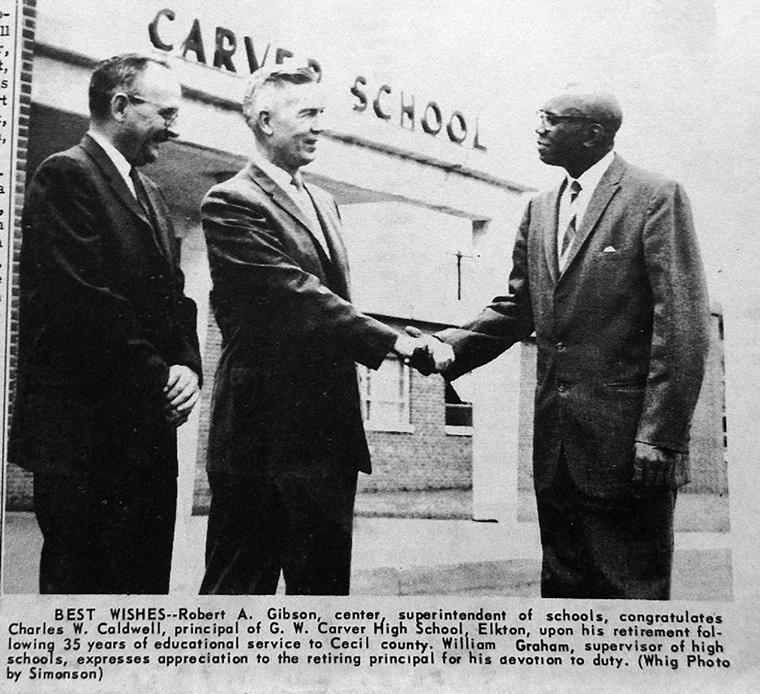

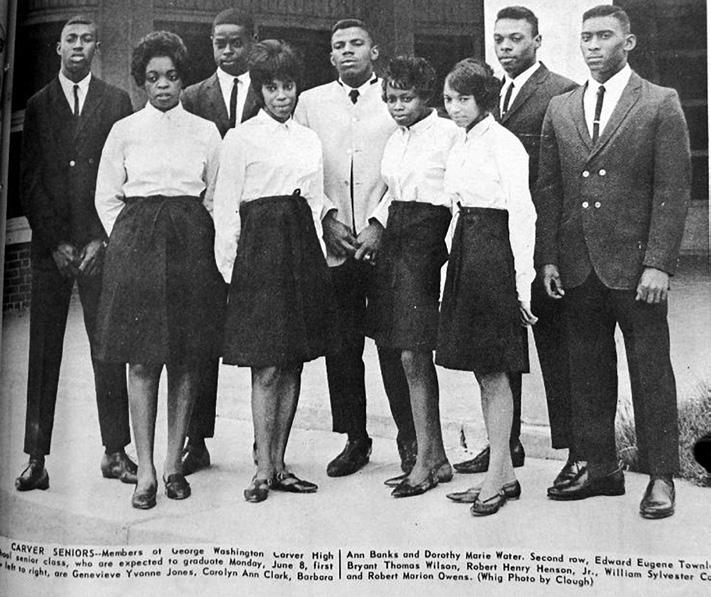

After the eighth grade, students at these schools had the option of taking a school bus ride of up to twenty miles to Elkton to the George Washington Carver High School. George Washington Carver served first grade through twelth grade.

The majority of these changes arrived after 1952, when Morris W. Rannels was appointed Superintendent of Cecil County Public Schools. During his tenure, Rannels was credited with the modernization of the school system in Cecil County. Shortly after Rannels’ arrival, African American students would now attend the George Washington Carver School, a school constructed in the period between 1953 and 1954. The new school building was officially dedicated on January 16, 1955. The former school building, which was constructed under the Rosenwald Fund, was converted into a storage facility for the school system maintenance department.

Cecil County however would not make any attempt to immediately integrate. Instead, a series of events, including a lawsuit filed against the Cecil County Board of Education in 1954, would ultimately start the long-winding journey.

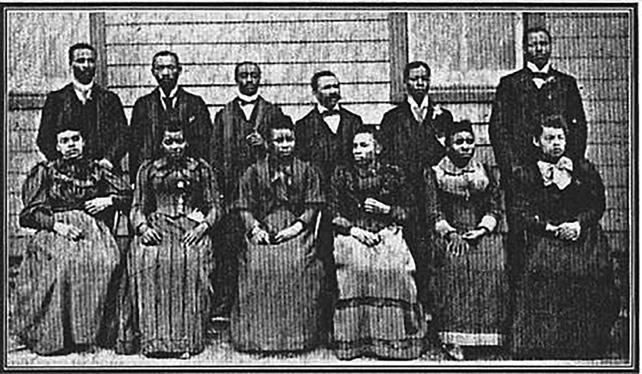

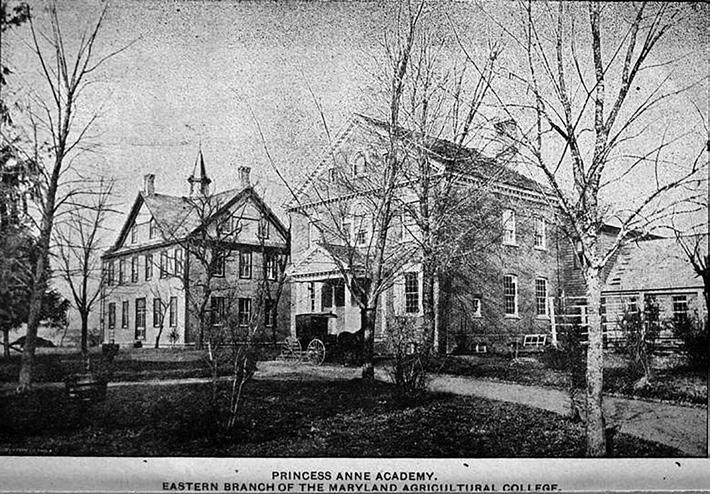

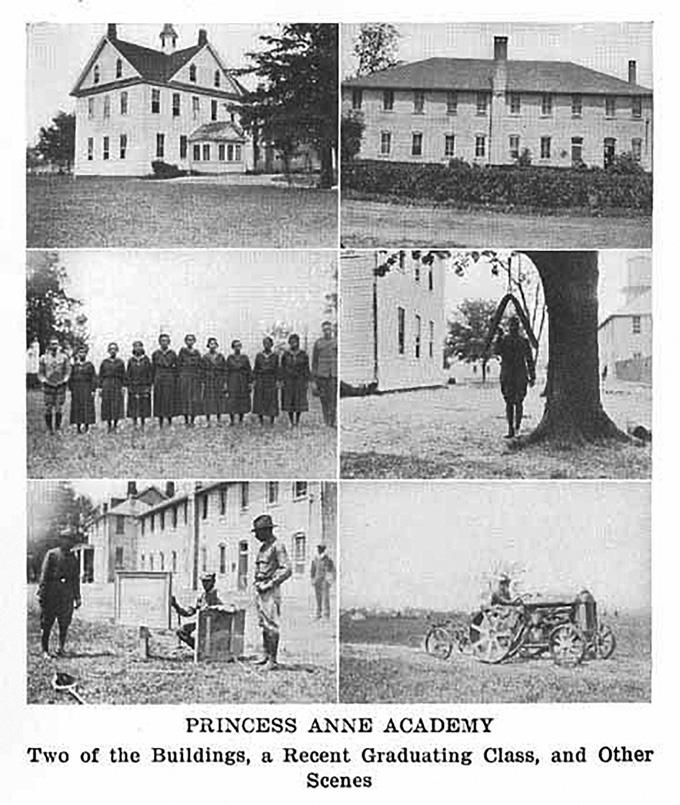

Princess Anne Academy

In May 1886, the Delaware Conference of the United Methodist Church created a school known as the Delaware Conference Academy, leading the movement of educating African-Americans on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Benjamin and Portia O. Bird opened the Princess Anne Academy in September 1886 and offered traditional collegiate courses with an emphasis on agricultural education. In 1896, the federally funded Land-Grant school had grown to include 6 faculty members and 93 students. The school offered Liberal Arts classes in addition to courses in shoemaking, carpentry, cooking, tailoring, and blacksmithing. In its first 11 years, 53 students graduated from the Academy. The State of Maryland took over the academy in 1926 and changed the name to Maryland State College in 1948 and, in 1970, the University of Maryland Eastern Shore.

From 1886 to 1897, Portia served as an instructor of physiology and elocution at the Princess Anne Academy. Following Benjamin’s death in 1897, Portia became principal, a position she held until her own death in 1899. The Bird family legacy continued through their daughter, Crystal, who served as the nation’s first African-American woman state legislator.

The Impact of the Historically Black

College Experience One Families Story of Love, Unity and Achievement

By Gary Fagan

Two sisters left the town of Bessemer, Alabama to begin a journey that would forever change a family’s story. Ovetta Marks invited her sister Helen to ride along with her to take her daughter to college. Helen had stolen away from her household duties to accompany her sister much to the disapproval of her husband Dan. Dan, a truck driver felt that Helen should remain at home to care for their children and strongly felt that her trip was an utter waste of time. The sisters reached their destination and spent all weekend settling Ovetta’s daughter into her college dormitory. Helen, who never traveled far from home was blown away by her experience that weekend. She never witnessed a place with such beautiful grounds and buildings and equally impressed by the hundreds of students busily preparing for their college experience. The place the ladies visit for the weekend was none other than Tuskegee Institute, the year was 1956. It was at this point Helen was INSPIRED !! and she had a thought. I want my children to come here. Helen returned from her weekend visit to Tuskegee with the determination to get her children enrolled in Tuskegee. At home all she talked about how beautiful Tuskegee Institute was and that she wanted her children to go there. Dan often got angry because all Helen would talk about was Tuskegee, how beautiful the buildings were and how smart the young black students looked. Dan and Helen had always stressed to their children the value of an education however they were raising a family of 10. By todays standard Dan and Helens living condition would best be described as poor. The possibility of their children going as far as high school and maybe a job at local plant seemed all too real. However, Helen had faith and Dan agreed to support sending one child to school to support the family. Dan and Helen went many days without to save what little money they could. After much planning, penny pitching and sacrifice. Rosalind, my sis-

ter enrolled into Tuskegee in the fall of 1962. What started as my parents desire to enroll one child into college ended some 30 years later. My parents successfully saw 13 of their children attend and graduate from Tuskegee University. From the fall of 1962 until my graduation in 1992 there was at least one of my brothers or sisters enrolled at Tuskegee. During this time period there were sometimes as many as four siblings enrolled in the same semester. Three of my other siblings earned degrees from other universities.

At an early age my parents stressed to each of us the value of getting an education. I knew as early as the 3rd grade that I was going on to college at Tuskegee. There was no thought given to going anywhere else. Although we grew up poor by todays standard, we never knew it because we received the love and support from our parents. I can recall many days attending middle school with ripped jeans and worn over shoes. Although the other kids in my class often made fun of my clothing, I knew I was bound for far greater things. When my father passed in 1978 my mom continued her mission to see us all get our education. My older brothers and sisters immediately pitched in coming home when they could and sending money home to support my mother as she worked to support us.

Tuskegee University a historically Black college was our second home. Tuskegee University and the legacy of education through our historically black colleges has been a part of our family story since that weekend in 1956. The feeling of family that I experienced on the campus of Tuskegee is that same feeling that you feel at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Howard, Fisk, Johnson C Smith etc. etc. I believe HBCU play a critical role in the preserving the African American cultural, intellectual and professional experience. While at Tuskegee I majored in Animal and Poultry Science where I earned my bachelor’s degree in 1992. I met my wife Cherita of 28 years during my days at Tuskegee. Cherita who is from Birmingham studied nursing while at Tuskegee and earned her Bachelor of

Science in Nursing in 1990. We married while I was a student and we started our family. During our time at Tuskegee we struggled financially however we did not let this deter our goal and dreams to succeed. Our fondest memories of Tuskegee would be the football games and then hanging out on the “yard “afterwards. And of course no HBCU experience would be complete without the bands!!!. My wife and I enjoy reminiscing about the good ole days on the campus. My biggest regret about my Tuskegee experience is not preparing myself enough in high school for the rigors of college academics. As a result, I struggled in math and science however I was determined to graduate. We moved to Maryland in 2001 along with our three children; Gary Jr. Brea and Kayla. We settled into our careers and raised our kids up to high school. We instilled in them that which was instilled in us and that was the value of education and the love we had for Tuskegee, our HBCU. Upon graduation from High School each of our children enrolled into the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. We are proud to say that each of our children successfully completed their degree programs at UMES. My children love and appreciation for there educational experience at UMES has shaped their character in a profoundly positive way. They each love and appreciate their HBCU experience. Gary received his degree in business administration, Brea received her degree in biology and Kayla received her degree in criminal justice. It was during this time I decided to go back and complete a master program in Food Science at UMES. I graduated with my master’s in food and Agricultural science in 2017. My wife continued her education in turn and received two master’s degrees in nursing and Hospital Administration in 2015.

My wife and I continued to encourage our children to achieve and strive higher with their education. There were many times when my wife, myself and our children would all be

continued on pg 35

at the dining room table studying in our respective disciplines. As result Kayla is currently enrolled in her second year of law school at North Carolina Central University and Brea is currently enrolled in Howard University school of medicine where she is studying to be a dentist. Our children believe now in the honor and privilege in receiving their education through our beloved HBCU’s. They believe as we do that, we have an obligation to improve our communities through education and hard work. I believe for the young African Ameri-

can student gaining an education at an HBCU gives the student a higher sense of awareness that may not be mimicked at non HBCU or even Ivy league schools. I fully appreciated my HBCU experience at Tuskegee and UMES and would not trade it for any offerings at Yale or Harvard. The sight of 3,000 to 5,000 people who looked like me, talked like me and had high dreams for their future. This image will remain with me. I really appreciate the teachers and staff who ensured that you EARNED your degree and it was not simply given to you or bought. What is most amazing about some the professors at HBCU’s is the fact they often forgo higher paying assignments at other institutions to remain at our schools to ensure that the best education is delivered .

My parents are gone, they leave behind in their children 16 college graduates, 10 honorably discharged veterans, 7 members of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity and a legacy of education through HBCU’s. Now it is up to us and our offspring to continue to journey toward improving our communities through education. Not for the sake of personal gains but for the sake of our kind. Historically black colleges have served as a repository of knowledge for us to improve our communities through education, hard work, application and above all service. My parent’s legacy of improvement through education and self-improvement and their unwavering love and sacrifice has forever changed our story.