46 minute read

Editorial

THE CRIMSON EDITORIAL BOARD Do Good Investments Make Good Neighbors?

As wildfires raged across New South Wales, Australia in late January, Harvard Management Company sold off its holdings in two Australian farms and purchased a minority stake in a produce company that operates on the other side of the world. By the time the fires were contained this past Thursday, 13 million acres of land and 2,500 homes had burned in New South Wales. 25 people had died. Of course, none of that probably mattered to HMC, nor to its profit margin; Harvard’s financial spectre was gone, presumably as quickly as it had arrived — now invested in South American avocados, not Australian almonds, let alone the livelihoods of the people who had grown them.

The fact that HMC invests directly in natural resources is itself unorthodox. If other large endowments do choose to invest in natural resources, they tend to do so through outside fund managers. HMC’s emphasis on natural resources stretches back to the 1990s and early aughts, when it saw strong profits in the sector. And between 2005 and 2013, HMC doubled down on the strategy. Since the financial crash, HMC has spent more than $1 billion to buy up more than 800,000 hectares of farmland around the world.

Some of these landholdings have put Harvard at odds with the surrounding communities. The University has received backlash for allegedly obstructing access to family burial sites in South Africa, causing health problems for locals in Brazil, and depleting already scarce water supplies in California. All of which should serve as a critical reminder that though HMC presumably engages in transactions involving land presumably to generate profit and diversify its portfolio, that land carries far more significance for the individuals in the community, whose homes and livelihoods depend on it. Land is where local communities build their lives; its value extends far beyond a number of hectares in a spreadsheet.

In light of this, we encourage Harvard to adopt an approach to its land and natural resource holdings that is more explicitly cognizant of the sensitivity that surrounds land ownership in any community, especially when such owners are thousands of miles away with no ties to the communities that they are impacting.

To be sure, the current CEO of HMC, N. P. “Narv” Narvekar, has changed tack significantly, overseeing a one billion dollar write-down in his first year and suggesting concerns about the risks some of these investments carry.

Still, even as HMC pulls back from natural resources, we hope it will work not just to maximize its own returns but also to be a good steward and neighbor in its natural resource endeavors. We do not view these two goals as conflicting; rather, we think that ideally, responsible stewardship and profitability should go hand in hand. HMC has already spoken to these goals in its Natural Resources Sustainable Investing Guidelines. But speech and action are not the same. And the morally ambiguous choice to sell its land holdings in New South Wales does not inspire our confidence.

HMC should not make further investments in land if it is not prepared to engage positively with the people who live there.

That said, for Harvard the issue is at once bigger and more local. The land it owns here in the City of Cambridge and in the surrounding areas is a product of the displacement of local residents, and before that, of indigenous peoples. How can the University even consider being a good steward abroad before it has come into that role in its own community? Harvard must be a community member of this land here in Cambridge, the land it holds throughout the United States, and the land it has acquired abroad.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Submit an Op-Ed Today!

The Crimson @thecrimson

When Dining Is Dangerous OP-ED

My mom was driving me home from the airport when I first listened to the 40-second voicemail from my doctor, confirming the results of my biopsy. I had just finished up my sophomore year at Harvard, and the last thing I was expecting was to be diagnosed with celiac disease.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease for which the only effective treatment is a lifelong gluten-free diet. I used to be an adventurous eater, but today, most food items scare me. Something that tastes good in the moment might leave me fully incapacitated for the rest of the day, lying in bed with a head-splitting migraine and stomach pain.

Sure, bread and pasta are off-limits. But, did the kitchen use clean utensils? Was the food prepared on shared surfaces? I have a million questions. When 20 parts per million of gluten threaten your health, every meal you eat represents a risk.

I took the fall semester off for an internship and learned how to manage my newfound restrictions while living on my own. But I was shocked to learn how difficult it would be to manage these same restrictions at Harvard. Last October, I visited campus, excited to see my blockmates and feel like a student again. However, walking into the dining hall, I felt a wave of stress wash over me. Sure, some of the ingredients were listed in minuscule print — but I had no way of knowing how the food had been prepared. I had no way of knowing if it would make me sick. I grabbed some fruit and choked back tears as I thought about how difficult navigating food at Harvard would be. I felt distinctly other, overlooked by the current system in place. All I wanted was to feel like a Harvard student again, but it was clear that with my diagnosis, Harvard no longer felt like home.

Given the lack of information online, I reached out to the Accessible Education Office and Harvard University Dining Services to learn more about how I was meant to navigate the dining halls. I learned that as a student with celiac, if I want to eat a safe meal, I should email By OLIVIA S. GRAHAM

a specific dining hall the day before and let them know what I want to eat. I am meant to follow this “email method” for all meals, every single day that I am on campus.

A big part of my Harvard experience has been spontaneity — I go to office hours and sometimes eat there. I eat with friends in their residential Houses. The current system of dietary accommodations unfairly constrains students with allergies, preventing them from freely participating in activities at Harvard. It should not be this difficult to access safe food.

I conducted an informal survey, and found that students on campus echoed

my concerns. Some students found themselves unable to eat in the dining halls, despite having to pay for an unlimited meal plan. Some had given up trying to obtain reasonable accommodations, defeated by a system that refused to listen to their concerns. Some students found the “email method” to be such an inconvenience that they parsed the ingredient lists instead, and sometimes suffered allergic reactions.

Think about that — the current system is so difficult that some students choose to risk their health rather than follow it. I was devastated. My peers had confirmed what I suspected: Living with a dietary restriction at Harvard is no easy task.

I spent hours speaking to the Dean of Students Office, the AEO, and HUDS, only to be told that the accommodations in place should be sufficient. My only frustration grew when I researched the protocols in place at peer institutions such as Stanford, Yale, Columbia, or Cornell and found that Harvard’s protocols greatly lagged behind them, rendering Harvard far less accessible to students with allergies or dietary restrictions.

At Stanford, for example, a full-time nutritionist works with allergic students to ensure accessible food options. Stanford Dining identifies the top 9 major allergens that are contained in, or may have come in contact with, the foods that they serve. Among the Ivy League, while Columbia, Yale, Cornell, and many others have already gone above and beyond to accommodate students with allergies, why has Harvard been so slow to identify top allergens on the serving line and hire a dietitian on the dining staff?

After my diagnosis, I found myself thinking about whether I would have chosen to attend Harvard had I been diagnosed earlier, given that other schools have far more robust programs in place to accommodate students like me.

When my younger sister was diagnosed with celiac disease a few months after me, I nearly cautioned her not to apply to Harvard. Eating at Harvard is a hassle. The friction inherent to the current accommodations is not only disappointing but embarrassing for the University as a whole.

After months of calling, it seems that the administration is finally beginning to understand: These protocols need to change. I appreciate the time that HUDS, the AEO, and Dean of the College Rakesh Khurana, as well as President Lawrence S. Bacow, have spent discussing this topic with me. I am especially thankful to Philip Zeller, my dining hall manager, who could not have been more helpful and accommodating throughout this process. But, I still cannot recommend this process to my sister: The system in place limits my ability to navigate Harvard freely.

I may be a Harvard student with celiac disease, but I am still a Harvard student. And I know one thing for sure: Harvard must do better.

COLUMN

Spherical Sheep

Woojin Lim and Daniel Shin THE CONVERSATION

You may have come across something like the following phrase in a physics textbook: “Assume the flying sheep is perfectly spherical.”

Though this is an unrealistic stipulation — for sheep don’t fly nor are they spherical — this hypothetical helps us develop a clearer understanding of the physical laws of motion while keeping all other variables constant.Beyond the confines of a physics textbook, ideal theorizing manifests itself in all realms of public discourse. A historical chain of thinkers — from Plato to Rawls — have sided with idealism over realism in thinking hard about philosophical questions.

Their inquiries begin to sound like something along the lines of: “What best principles would fully informed, impartial, and rational agents in an ideal society reach when deliberating about matters of morality or justice?”

Ideal theorizing happens as we sit back in the reclusive perches of the philosophers’ armchair, distancing ourselves from the world as it really is. We depart from realism in its strictest sense. Heads in the clouds, we toy around with high-level thought experiments replete with ‘what-ifs,’ whiting out real-life barriers and feasibility constraints. Everything is easily solved. The real world as we experience it, however, is imperfect. We conduct ethics in a broken world. Both knowingly and unknowingly, we are prone to making irrational, partial, flawed, and deficient moral judgements. Even the most devoted Kantians (and I can tell you, I know plenty of Kantians running around campus) fail to act strictly on maxims through which they can, at the same time, will as a universal law.

Natural inclinations and emotions seep through the veil of pure practical reason. Outliers run rampant: criminals, psychopaths, amoralists, the list goes on and on.

If our understanding of morality can be only realized for perfectly situated agents living under utopic conditions, the term ‘everyday ethics’

seems like an oxymoron.

Morality in all of its flawlessness might just be a Tantalean spring, perpetually out of reach. Stuck in the depths of Hades, Tantalus, son of Zeus, is condemned to an eternity of hunger and thirst; the fruits hanging on the tree above him forever elude his grasp, and the water always recedes before he drinks. His aim to attain an unattainable state of satisfaction is itself an impossible demand.

Following a similar vein, global human rights activism, for many, is disenchanting. No matter how valiant one’s altruistic intentions, it often appears that large-scale institutional and structural change is virtually impossible to realize, provided the unwillingness of the current political climate. ‘What-ifs’ devolve into ‘if-onlys.’ The blame game can be played by many.

A number of possible responses present themselves. Throwing darts of radical skepticism and charges of hypocrisy about activism might be one answer. Another way out of this paralysis is to bend our moral standards so as to conform to our natural inclinations.

We could just lower the bar. Although this strategy avoids the problem of facing existential despair and moral futility, it comes at the expense of inducing an attitude of moral complacency. These proposals cave into premature forfeit.

The project of non-ideal theory emerges as a third alternative. It seeks to bridge the gap between principle and practice, thought and action, philosophy and policy, without having to abandon ideal theory in a world short of the ideal. Non-ideal theory often draws from the empirical social sciences, articulating principles designed to cope with current injustices from the ground up. It asks how we should resolve our felt social and political problems, inching towards making unjust societies more just. For even if we are unlikely to satisfactorily attain the golden mean of virtue, it could still be worth thinking about how we might.

While the spherical sheep flying in an isolated vacuum is certainly not a real sheep to most of us (aside from physicists and whoever did the CGI effects for the Cats movie), this deliberate setting aside of complications helps us to elucidate the most significant moving parts, all else equal, one at a time. Both by virtue of its elucidations and its aspirations, ideal theory provides both a starting point and an endpoint.

Understanding what constitutes ‘imperfections,’ that is, deviations from the ideal, is impossible without having defined the standard of what ‘perfection’ stands for in advance.

The architect’s blueprints lend guidance to the builder’s craft. Even if the perfect building can never be built, we might as well do our best to close the distance between the imperfect and the perfect.

The very process of critically thinking, reflecting, (re)drafting, and sharpening our approach to the ideal through the non-ideal is a measure of growth, a statement of effort. For as long as we’re trying, we’re on the right path.

ARTS

CAMPUS

Elizabeth Banks Raps and Duels at the Hasty Pudding’s Woman of the Year Roast

COURTESY OF RYAN N. GAJARAWALA

JOY C. ASHFORD CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Aided by their traditionally eccentric parade and zany traditions, the Hasty Pudding Theatricals took to the streets on Jan. 31 to honor their 70th Woman of the Year, Elizabeth Banks.

Famous for her acting roles in “The Hunger Games,” “30 Rock,” and “The Lego Movie,” Banks also directed and produced films including “Charlie’s Angels” and “Pitch Perfect 2,” the second of which set a box office record for a first-time director. Banks, who describes herself as a feminist, joined the Hasty Pudding’s second-ever cast to accept female performers, and the first to perform a show co-written by a woman.

After a parade of drummers, musicians, dancers, and Milk Bar brand ambassadors brought her to Farkas Hall, Banks got ready for, she said, “a very unique experience.” To receive her traditional pudding pot, she first had to endure a roast that seared numerous aspects of her career. No stone went unturned — neither the time she was the third woman ever to receive the “coveted” Razzy award for worst director, nor her receipt of an MFA from the American Conservatory Theater.

“It’s fitting, because you are a master of creating art that is fine,” Scott Kall ’20 said. Kall and Eli W. Russell ’20 also quoted Banks’s tweet from several years ago in reference to “Pitch Perfect 2”: “If you’re going to have a flop, make sure your name is on it at least 4x.”

“That must be why all of your films say “‘Elizabeth Banks Elizabeth Banks Elizabeth Banks Elizabeth Banks,’” Russell said.

In addition to jokes at the expense of her acting career, Banks also completed a series of tasks inspired by some of her more memorable or embarrassing onscreen moments. Along with extemporaneously rapping Vanilla Ice’s “Ice Ice Baby,” she ate a burger immediately before kissing a lifesize picture of Paul Rudd’s head and took on “Beezel the Cat” (from Banks’ “Movie 43”) in a foam sword duel.

“I haven’t beat anybody up in a while, and it was really fun!” she said.

Following the duel, Banks delivered a monologue from “Romeo and Juliet” that ended in the line, ‘Pitch Perfect 2’ had pretty much the same plot as ‘Pitch Perfect 1.’” “That’s how franchises work, guys,” she said. In fact, she delivered a few roasts of her own — jabbing not only at the Hasty Pudding, but at her Harvard audience as well.

“The Hasty Pudding is just one of those truly progressive organizations,” she said. “It’s like you were founded and then, a mere 175 years later, let ladies into the party.”

When asked about the University of Pennsylvania, her alma mater, Banks eagerly answered that she would never wear a Harvard sweatshirt.

“Penn is a much better institution,” she said. “If Ivies were Kardashians, we’re Khloe — we’re bigger and more fun, and we’re easier to get into.”

Following the roast, Banks attended a press conference where she answered questions about her first acting role (as a high school senior) and Oscar predictions (Greta Gerwig winning Best Screenplay and “seeing Brad Pitt in nice clothes.”

“Whenever I get to take a stage I try to do my best to somehow roast my husband,” she said. “We’ve been together for a long time — it’s our 28th year — and I looked out while I was being roasted and he was having the best time.”

“We were just working on a television show for FX called ‘Mrs. America,’ with one of the finest casts that I’ve ever been a part of — Cate Blanchett, Sarah Paulson, Uzo Aduba, Margo Martindale. I think every single person [in the cast] is the greatest, and I’ve just been having the best time,” Banks said.

Finally, she answered a question on co-owning her production company, Brownstone Productions, with her husband Max Handelman.

“It’s fun to go to work together everyday, and we get to travel as a family, which is really important,” Banks said. “I think especially for women working in Hollywood, it’s important to build your support system so that you can do as much as you want to, and I have a great support system in my husband and in the employees at my company.”

Staff Writer Joy C. Ashford can be reached at joy. ashford@thecrimson.com.

THE WEEK IN ARTS

14

FRIDAY

‘CASABLANCA’ AT THE BRATTLE Celebrate this Valentine’s Day with a showing of the classic Bogart flick in 35mm. The Brattle. February 14 at 4-6 p.m. $9, $10.

15

16

17

18

19

20

SATURDAY THREADS OF CONNECTION

The ICA unveils a new installation designed in collaboration with local fiber artist Merill Comeau. Institute of Contemporary Art. February 15 at 12-4 p.m. Free with ICA admission.

SUNDAY SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL SHORT FILM TOUR Enjoy a theatrical program of seven short films from around the world selected from the 2019 festival.

Institute of Contemporary Art. February 16 at 1 p.m., 3 p.m. $5, $10.

MONDAY DIRECTOR IN PERSON: ‘RECORDER: THE MARION STOKES PROJECT’ Enjoy a showing of the documentary film about Marion Stokes and the massive television news archive she recorded. Harvard Film Archive. Feb. 17 at 7 p.m. $12.

TUESDAY DAVID MICHAELS IN CONVERSATION WITH LAWRENCE LESSIG David Michaels discusses his book, with author and Harvard Law professor Lawrence Lessig.. Harvard Book Store. Feb. 18 at 7 p.m. Free.

WEDNESDAY VISITING ARTIST LECTURE WITH HAYNE BAYLESS

Join the potter who won top awards at the Smithsonian Craft Show for a master class on ceramics. Harvard Ceramics Program. February 19 at 12-1 p.m. Free.

THURSDAY AFTERGLOW AT OBERON: KAREEM LUCAS

Kareem Lucas’ show, “The Maturation of an Inconvenient Negro (or iNegro)” features poetry, prose, and an original jazz composition. Oberon. February 20 at 8 p.m. $25.

14 FEBRUARY 2019 | Vol CXLVI, ISSUE XVII

Arts Chairs Iris M. Lewis ‘21 Allison J. Scharmann ’21

Editor Associates Hunter T. Baldwin ’22 Joy C. Ashford ’22 Kalos K. Chu ’22 Connor S. Dowd ’22 Annie Harrigan ’22 Cassandra Luca ’22 Samantha J. O’Connell ’22 Amelia F. Roth-Dishy ’22 Jack M. Schroeder ’22 Lanz Aaron G. Tan ’22

Executive Designers Ashley E. Bryant ‘22 Meera S. Nair ‘23

Executive Photogra- pher Jenny M. Lu ’22

Design Associates Maia R. Zonis ‘22 Miranda Eng ‘22

CAMPUS

Ben Platt Talks Theater, Hot Dogs, and Jewish Tradition at Hasty Pudding Man of the Year Ceremony

SOFIA ANDRADE CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

“I would say that it’s hard for me to feel any kind of real connection with the city until I meet the theater people within that city. And so now I’ve met those people and I feel much more connected to them,” said Broadway star and Hasty Pudding honoree Ben Platt at the Hasty Pudding’s annual Man of the Year celebration.

On Feb. 7, Platt was celebrated with a roast led by Hasty Pudding producers Natalie F. Needle ’21 and Samantha J. Meade ’21. The roast was followed by the premiere of the Hasty Pudding’s 2020 musical production, “Mean Ghouls.”

During the roast, Platt was subjected to quips about his age and his affinity for playing “anxious weirdos” in everything from television to film to the great white way. He was also challenged to a sing-off in defense of his honor with a rendition of Nina Simone’s “Feeling Good,” then acted out the ending to the fifth book from the Harry Potter series, after he revealed that he had stolen the book from another Ben at summer camp.

He was also asked to channel his character on Netflix’s “The Politician” while defending the status of hot dogs.

“I think we should be leaning towards connection and togetherness… Therefore, a hot dog is a sandwich,” he said, before ending his speech with a cry of “Anyone but Trump 2020!”

Once he completed the various tasks required of him, Platt received his honorary Pudding Pot. “I’m very honored to be on this list of men and women… and I’m going to put beautiful candies in here, thank you,” he said, donning a sparkly bra offered up by Pudding cast members.

At a subsequent press conference, Platt spoke of the importance of forming deep connections with his cast members and of his love for theater.

“I think I really value the opportunity to keep pushing back and forth [between theater, film, music, and television] because it allows me to appreciate the things about the other mediums that I’m missing or that I’m not really getting involved in. But I think theatre will always be my home and what I’m most passionate about,” Platt said. “That’s always where I feel the most comfortable, the most myself.”

When asked about how his Jewish heritage affected the way he approached his work, Platt cited the ways in which he connects with his coworkers.

“I would just say my inclination to turn every sort of cast into a family comes from my Jewish upbringing. I think because I was encouraged to share my feelings and thoughts and to open myself up to people I love,” he said. “Now I go into every experience looking to make that kind of a bond with everybody, whether that’s a piece of theater or my cast on ‘The Politician’ or a film cast.”

Platt ended the conference with a reflection on his time in the limelight and the importance of a good relationship with his family.

“I think it’s very easy for you to kind of lose yourself,” he said. “I’m really fortunate in that I have a really wonderful family that keeps me very close to the ground. I have a lot of nephews and siblings and parents who are very supportive and want to share these moments with me. I could really care less about any of this. At the end of the day, I just want to be around the table with them.”

Staff Writer Sofia Andrade can be reached at sofia.andrade@thecrimson.com.

COURTESY OF ALLISON G. LEE

The latest on music, film, theater, and culture.

That’s artsy.

The Crimson thecrimson.com/arts

Portrait of an Artist: Echosmith’s Sydney Sierota

IRIS M. LEWIS CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

After a seven year break, the multi-platinum pop group Echosmith is back with their sophomore album, “Lonely Generation.” The band found fame in 2013 with hit single “Cool Kids.” At the time, singer Sydney G. Sierota was a high school sophomore. Now she’s 22 and married. The Crimson sat down with Sierota to talk about what’s changed, what’s stayed the same, and what inspires Echosmith almost a decade later.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity. The Harvard Crimson: It seems like you focus on isolation in both “Cool Kids” and “Lonely Generation.” Is writing about loneliness different now than it was seven years ago? Sydney G. Sierota: I would say, unfortunately, it’s become more relevant now than it ever has been. Social media did exist when “Cool Kids” was written, but it wasn’t as big of a deal as it is now. I literally don’t know a single person who doesn’t have social media. That’s pretty crazy. When “Cool Kids” was written, I knew plenty of people who didn’t have it yet. I was still a sophomore in high school. Life has changed so much in the past seven years, and I think the importance of social media has really hurt our generation. We’re all so caught up in what other people think about us, and in presenting a perfect version of ourselves… But that’s not reality. I think it’s really pulled us away from being authentic and true to who we are — which is what “Cool Kids” is about, at the end of the day. THC: How do you balance needing to use social media for your brand with that skepticism about loneliness?

SGS: It’s hard to find a balance between both. Obviously, with what I do, it’s really important that we’re on social media, that we’re active on there and responding to as many fans as we can. We love getting to talk to our fans and interact no matter where we are…. But I try to limit myself in a personal way from scrolling too much. My screen time is way too high right now. I’m trying to find the balance between seeing what’s going on, in a healthy way, and then stopping myself before I start comparing myself to this perfectly edited version of somebody.

THC: A lot of the buzz around this album has been about social media. Is that the element of the album you’re most excited about?

SGS: There’s a lot of themes and feelings inside of this album. There are a lot that have come from this world of social media, and what does that mean and how do we feel about it. But there’s also so

COURTESY OF JUSTIN HIGUCHI/WIKIMEDIA

many other layers to my life that I got to talk about on this album. I think that’s really special, because with the first album I was only 16. Now I’m 22 and I’ve learned so much more. I’m married. I got to fall in love and experience that firsthand instead of just dreaming about it, watching movies about it, and hoping one day, I could feel that too. So lyrically, we got to really dig in to that part of me. It felt really special to do that. It felt really special to be so vulnerable…. I mean, anybody can really relate to the themes of this album, which are coming of age, finding who you are, and also falling in love and discovering what all that means to you. How does it make you feel — the good, the bad, the in between? The things that are kind of hard to talk about are really important to talk about, too, and that’s something we wanted to address on this album. THC: Those are some heavy topics, and it sounds like they must have taken vulnerability. Was any part of this album especially challenging to make?

SGS: In a personal way, it was very challenging to just be vulnerable, period. In my personal life, even with friends and sometimes even family, I tend to just tell everyone that everything is great, no worries, life is perfect, and I’m good — even when sometimes I’m not. It was really a personal stretch, and a professional stretch, and a creative stretch, to tell myself to be vulnerable and to go there even when it felt scary.… It was definitely hard to push myself to do that, and also to have the guts to actually say, “Okay, let’s put that on the album and let anyone and everyone hear it.” But I’m really grateful that I did that because I’ve already got so many messages of people saying that they relate…. That’s the perfect response to me being vulnerable, especially when I felt scared to be. It inspired me to just keep doing that — keep digging in deeper to all the different parts of myself and sharing it with whoever needs to hear it.

Staff writer Iris M. Lewis can be reached at iris.lewis@thecrimson.com.

THEATER

An Interview with Royal Ballet Director Kevin O’Hare

JOY C. ASHFORD CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Kevin O’Hare has been Director of the Royal Ballet, the UK’s foremost ballet company, since 2012. In advance of the company’s Christmas adaptation of “Coppélia,” opening in select US theaters this January, The Harvard Crimson spoke with O’Hare about his vision for the company, the company’s new cinema program, and the future of ballet on film.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Harvard Crimson: Thanks so much for sitting down with us! You started studying at the Royal Ballet when you were 11. How have you seen it change since then? Kevin O’Hare: I hate to think about it, but I’ve now been connected with the Royal Ballet for 42 years.

I think some things that haven’t changed are our commitment to telling stories, to really bringing the audience along in whatever that story is. We’re not just about two people dancing in the middle of the stage — everybody on stage is telling that story, everybody is important in that storytelling.

What has changed is the collaboration with so many different artists, which is really fantastic. I would say the physicality of the dancers is quite something. When I look at what they do now on stage, I think, gosh, I can’t even imagine myself doing that when I was dancing. They’re constantly pushing their body to its limits and really exploring what you can do within classical ballet. We’ve learned so much about how to use our bodies, and how to look after them. There are great dancers of the past [who] could give as much as the dancers of today, but it’s just a very different way of movement quality. THC: You’ve said “without risk there’s no progress.” What’s the most risky thing you’re doing this season? KO: Every time you put on a new ballet, it’s a risk. You’re putting yourself out there, putting the company out there. As director, when I’m nurturing young dancers, putting them on stage, giving them their first opportunity, that’s a risk. But they’re all calculated risks, and I think I’m really very confident in the results.

Just before the first night of “Woolf Works,” which was Wayne McGregor’s first full-evening ballet for us, I was sitting out there watching the dress rehearsal, just thinking, this is something new, this is something different from anything else we’ve ever done before. And that’s fantastic and that’s when it’s worth taking those risks. And I think that’s what we’ll be doing again with these new creations. THC: Do you see film as a threat to live ballet performance in any capacity, a new opportunity, or something of both? KO: I don’t see it as a threat. What I found really fascinating was that this year, when we toured in Japan, you felt that people really wanted to see the dancers, and they knew the dancers, and that was through the cinema program and what you see online.

And I noticed that in LA as well, the first night they were screaming dancers’ names when they came out. The two are actually helping each other, I think. Because we’re one of the companies that has the most of these cinema relays coming out every year. THC: What is it about the Royal Ballet’s approach that takes it beyond the technique? KO: I think we’re very keen on making things as natural as possible. Of course, the ladies will be in pointe shoes and the guys will be in tights. We try to be as natural as possible, and [have] the emotions as real as possible, and I think that is the key to drawing people in. You have to reach those people that are in the atmosphere of the Royal Opera House, but it’s the same way as you’re reaching that person in the cinema who’s really close to you. And I think you do that not just by some exaggerated way of telling the story — it really has to come from believing in it. That’s what we try to bring to the dancers. So I think it’s really important for us that we treat everything as naturally as possible.

THE HARVARD CRIMSON | FEBRUARY 14, 2020 | PAGE 8

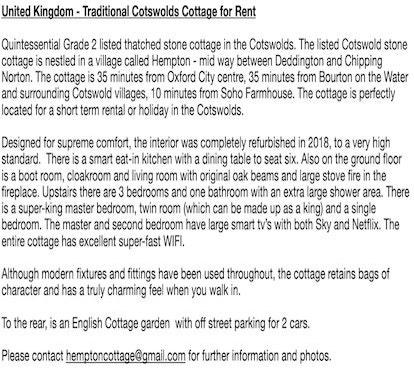

In ‘Oligarchy,’ Satire Is Cruelty

ARTS

CAROLINE E. TEW CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Scarlett Thomas’ latest novel “Oligarchy” is billed as a comedic look at the pressures girls face — mainly being beautiful and thin. It’s a novel that is “trying to give [readers] some moral instruction, some basic feminist grounding,” just as Aunt Sonja does for the main character, Tash. But just as Aunt Sonja rails against eating disorders right before Tash falls asleep to “the familiar sound of Aunt Sonja vomiting in her bathroom,” this novel doesn’t practice what it preaches. While there are occasional lines that are laughout-loud funny, others try too hard to be outlandish. The most problematic parts of the novel are the characters’ complete lack of depth and the biting satire that only ends up painting girls who suffer from eating disorders as vapid.

The book’s title and blurb is misleading insofar as it highlights Tash’s Russian background and connection to the oligarchy. Throughout the novel, it becomes clear that Tash has not always known her father was an oligarch and that he sent her away to a British boarding school. However, instead of an intriguing backstory, the Russian connection serves almost as an excuse to have a look at the school. Packages from an occasionally-mentioned Nico, who Tash “hates ... so much,” hints at something more interesting to come. But the connection to oligarchy and Russia serves no purpose other than as a shoddy backdrop.

The language oscillates between witty and overdone.There are funny moments (“‘Because of capitalism, Lissa. Because of your fathers and what they do.’ ‘Sir, that’s sexist! Some of our mothers might be capitalists too!’”), and other moments that feel overwrought and childish (“Tash searches alone for the little grave, amongst the sharp green erections of the late-spring flowers”). The novel is meant to be satirical, and when done well it packs a punch. But unfortunately “Oligarchy” is chock-full of misses, all of which feel forced.

But the novel’s biggest flaw is its callous treatment of eating disorders. In theory, “Oligarchy” is meant to illuminate the stressors placed on girls in institutions like boarding schools. In an effort at satire, Thomas has created a boarding school with an eating disorder epidemic: Specialists are brought in to give talks, girls are constantly rotating through various extreme diets, and at least one student has died from anorexia. Instead of looking upon these girls with empathy, “Oligarchy” routinely describes these girls as shallow and elitist products of their rich parents. On top of that, the novel routinely presents a troubling binary — be thin, beautiful, and miserable or fat, ugly, and possibly happy — as if there is no way to be pretty if not thin or thin if not miserable.

The characters are reduced to mere caricatures. There is “Becky with the bad hair” who is ostracized mostly due to her appearance, which doesn’t fit the standard set by the other girls. There is Rachel, who learns that she could gain social clout if she were skinnier and who thus starves herself for popularity. And while many of the adults at the school are complicit in perpetuating an atmosphere that encourages eating disorders (such as a science teacher who lets the already malnourished students weigh themselves and check one anothers’ BMIs in class to analyze the data, the satirical nature of the book almost seems to point a finger at the girls themselves for having eating disorders. The girls are portrayed without any particular sympathy and appear to be the catalysts for one anothers’ disorders. While “Oligarchy” attempts to show the toxic nature of such institutions, the book instead depicts an echo chamber in which these girls have knowingly created their own hell and seems to punish them for it.

Though the novel is short, the end comes as a relief. The mys

COURTESY OF COUNTERPOINT PRESS

tery teased in the book’s synopsis concludes in the most lackluster way possible, and finally the 200 pages devoted to poking fun at girls suffering from anorexia are over. The novel is overwhelming and painful to read — which, of course, may be a point Thomas is trying to make about eating disorders — but much of what feels oppressive are the depictions of the girls that paint them as shallow and gullible, with nothing much to contribute besides their thin bodies.

Staff writer Caroline E. Tew can be reached at caroline.tew@ thecrimson.com.

Portrait of An Artist: Levan Akin

GABRIELLA M. LOMBARDO CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

In his third feature film, “And Then We Danced,” director Levan Akin struck gold: After a 15 minute standing ovation at Cannes, the indie darling was decorated at festivals from Odessa to Sarajevo. Although Akin’s native Sweden selected the film as its Oscars submission for Best International Feature and heaped Guldbagge awards atop its well-laureled head, the story has been anything but congratulatory in the film’s country of origin, Georgia. Far right, pro-Russian conservatives flooded November screenings in Tbilisi and Batumi to protest the film’s portrayal of the homosexual romance between its main characters, Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani) and Irakli (Bachi Valishvili). We spoke with Akin about the controversy surrounding the film and how his Georgian heritage motivated a tale of identity conflicting with tradition.

Note: the following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. The Harvard Crimson: You’ve stated that the attacks at the 2013 Tbilisi pride parade inspired this story, and I understand you had a difficult time getting this film made due to its subject matter. Were you afraid at any point during the project? Levan Akin: I wasn’t that afraid, actually. I was more angry. In Georgia, it’s legal to be gay. They’ve been protected under the law since the year 2000. On paper, it’s one of the most progressive countries in the region, but that’s not implemented in real life. The far right people have so much space to exist. While we were filming, we were in contact with the municipality of Tbilisi asking, “We want to film in this location. Is that okay?” They would say “yes,” and inevitably, they would find out what the film was about and with two days’ notice, sometimes one day’s notice, say, “No, we’re suddenly renovating.” That really pissed me off because they were supposed to support us. I mean, we’re allowed to make a film about whatever we want. THC: You’ve described the film as a coming of age story, not a coming out story. Can you speak more to that distinction? LA: To me, the film is about self-realization. In the film, Merab never questions his sexuality or becomes angry about it or sad or afraid. He just embraces that he’s in love, which was very important to me. And through that love, he finds his place in this society that does not accept him, and he decides to break free from it. THC: As a person of Georgian descent born in Sweden, did you draw on your own personal experience while writing the script? LA: Yeah, I did. I grew up in Sweden, but the Georgian culture was always present. I wanted to make a celebration of Georgian tradition and culture. And the family dynamic is so important. That’s also because of the economic situation. People are really struggling. You have to have this sense of community to survive. And I wanted to show the viewer what Merab potentially could lose by following his heart. He wouldn’t only lose the love of his life, which is dance, but also his family. Change and movement is something that defines humanity, and that was something that I was thinking about a lot while making the film. THC: The modernist take that the world is in flux was captured with the cinematography. It has a documentary feel, and there aren’t many wide shots. Can you explain the impetus behind that style of filming? LA: That style of filming was also very much a practical matter. We had a lot of trouble shooting the film because of how flexible we had to be all the time. We had very little money. We had little time. And we would lose locations. So, it’s like art out of necessity in a way. THC: Could you speak more to the challenges of making a film like this in Georgia? LA: I had to be very flexible. I couldn’t really plan out the movie as I usually do, which was fun because it kept my curiosity alive all the time. But I would write the script while we were shooting sometimes because I had to change so many things and I worked a lot with amateurs — with people I met doing research. And a lot of the scenes were filmed in the moment, like the scene with the sex workers.

They were working that night and we just came and filmed. It became this neorealist approach to filming. All the locations are real. We didn’t change things with production design. The actors are wearing their own clothes for most of the film. We had barely any makeup. It was very bare-bones. I think that’s why it feels so real, too. THC: I was so moved by the connection between Merab and Mary, and then I learned that those actors have actually been friends since they were very young. LA: I know, I know. And I mean Levan (Merab) wasn’t even an

COURTESY OF MUSIC BOX FILMS

actor. He’s a dancer. I found him on Instagram. And Mary had acted and they had known each other since they were thirteen years old, which is so sweet. So I just built off what I found. THC: Do you feel a great sense of community with your cast and crew, along with the people who love this film? LA: I do, I do. I feel that a lot. But, on the other hand, sometimes I also feel a little isolated and a little outside everything because, you know, they are all in Georgia, all together. And I’m in Sweden or New York or wherever I am at the moment. I don’t know anymore. I’m traveling all the time. And sometimes I feel sort of like an outsider, but I guess that’s what also enabled me to make the film in the first place. THC: I want to ask you more about this notion of feeling isolated. It seems like films with the most empathy for a character are really about looking at someone who is isolated and opening them up to the audience. Do you feel that’s what you did with your main character, Merab? LA: I think all my movies, in some way, have been about outsiders and isolated people. And I think that comes with — you know, I was born and raised in Sweden, a country which I love. But I’ve been reminded my whole life, from time to time, that I’m not really Swedish, either. You know, there’s a lot of racism in Sweden at the moment. You just feel like you don’t really have a place that’s yours. And I think that’s definitely impacted the types of stories that I’ve chosen to tell. But I think because I’ve sort of been hiding in my previous works, with this film I sort of threw everything out the window and I did something that was just purely coming from a place of excitement and love and curiosity. I’m always going to work like that from now on. If I don’t find an entry point that really, really interests me, I won’t do it. THC: So, what comes next for you? LA: I’m actually going to Istanbul to research my next film. I don’t know if I will actually make a film in Istanbul, but I have some things, some stories that I’ve heard, that are set there. And I love the city, so I want to go there and see if I find something interesting, some interesting person, that could inspire a story that feels relevant.

Political Reporters Analyze 2020 Campaign Trail

By EMA R. SCHUMER CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Four journalists covering the presidential election discussed uncertainty in the 2020 Democratic primaries and experiences with day-to-day reporting on the campaign trail at the Institute of Politics Thursday evening.

Moderated by IOP Senior Fellow and Washington Post Chief Correspondent Daniel “Dan” J. Balz, the conversation featured New York Times reporter Astead W. Herndon, Washington Post reporter Sean Sullivan, NBC News reporter Josh Lederman, and CNN correspondent Arlette Saenz.

Lederman said President Donald J. Trump’s ascent to the White House in 2016 — which confounded much of the media at the time — looms large in the minds of journalists covering the unfolding presidential race. “The biggest challenge is that despite all of the postmortems that we all did after 2016, no one has really put their finger on exactly what it is that we got wrong,” he said. “There’s been different theories around that but no one’s really sort of diagnosed that in a way that’s given people confidence that we can move forward with a better sense of what’s actually happening.”

Herndon said the media’s overall inability to recognize Trump’s appeal to voters during the 2016 election demonstrated that journalists have “real blind spots.” To improve their ability to report on the electorate, Herndon said, media outlets should recruit a more diverse workforce.“We have to do better at getting folks who are coming from different places, who look differently, who think differently,” he said.

Despite uncertainty about who will clinch the nomination, panelists agreed that electibility is the foremost criteria Democratic voters are looking for in the current pool of candidates. Sullivan said he believes a definition of electability remains elusive among the electorate.

“A lot of Democratic voters are still shopping around,” he said. “They’re still uncertain about that central question which keeps coming up, which is who can defeat President Trump.”Given the constant stream of news, Sullivan said, any one moment can shape the outcome of the race.

“Literally anything can happen in this race that can immediately become a massive story — a big front-page story — and a moment that begs explanation and understanding,” he said.

Panelists also exchanged anecdotes describing the vicissitudes of life on the campaign trail. Herndon said he lost his backpack and credit card and ran out of gas on the highway all in one day this week.Despite these challenges, Saenz said she is passionate about her work.

“I love being on the road, mostly because we have a front row seat to history and we’re able to relay that to so many people and help people as they build their decision about who they’re going to elect as their next president,” she said.

Sruthi Palaniappan ’20 said she left the conversation with an augmented appreciation for the media. “They’re on the ground 24/7 trying to figure out every candidate’s next move,” she said. “So the life of a reporter is definitely not easy, but important.”modo ligula eget do

ema.schumer@thecrimson.com

During the second forum of the Institute of Politics’ 2020 Election series, four political correspondents reflected on the state of the presidential race. JENNY M. LU—CRIMSON PHOTOGRAPHER

ALLERGY FROM PAGE 1 Students With Allergies Struggle Navigating HUDS

It is an autoimmune disease.”

Alexa C. Jordan ’22, who is allergic to tree nuts, said ingesting nuts has regularly caused her to go into anaphylactic shock.

Though she has not had a reaction in a Harvard University Dining Services dining hall, she said that incomplete or inadequate labeling — that which fails to bold or highlight common allergens — has resulted in several close calls.

HUDS Director for Strategic Initiatives and Communications Crista Martin wrote in an email that menu cards in Harvard dining halls only have partial ingredient lists due to space constraints.

However, students can find complete lists of ingredients and top allergens — in addition to gluten, pork, and alcohol — on the HUDS website, Crista added.

HUDS also began listing top allergens and gluten on dining hall menu cards this semester. Manning said cross-contamination in Harvard dining halls — particularly Annenberg — is a “nightmare” due to its self-service model.

She gave the example of students serving themself green beans with a spoon and accidentally touching a piece of bread on their plate.

“Well, now I can’t have the green beans, but there’s no way for me to watch every single person and see where the stuff goes,” she said.

Martin wrote that preventing cross-contamination entirely is impossible, but that HUDS staff members are trained on food allergies and gluten-free diets on an “ongoing basis.”

Basic practices to avoid cross-contamination include regularly changing gloves and cutting surfaces. HUDS also staffs heavily trafficked areas like salad bars and entrée stations during peak meal times to monitor the cleanliness and safety of dishes and to swap utensils as needed, Martin wrote.

In order to avail themselves of individualized meal plans, students with dietary restrictions can register for accommodations directly with Harvard’s Accessible Education Office.

During preliminary meetings, the AEO and HUDS walk students through platforms for accessing ingredient information and other resources — including a daily email ordering system for meals — College spokesperson Rachael Dane wrote.

The office helps students create individualized plans that allow them to safely and comfortably dine.

However, some students said they feel individualization comes with drawbacks. Olivia S. Graham ’21, who also has celiac disease, said it forces students with restrictions to “reinvent the wheel.”

“You essentially start from square zero,” Graham said. “It makes your world feel a little more narrow because you have no idea what’s been done previously or if maybe they’ve accommodated students like you

You essentially start from square zero.

Olivia S. Graham ’21 Student

in the past.”

Some students said that, despite measures HUDS and the AEO take to provide special accommodations, they have considered trying to go off the meal plan altogether.

Graham said that for students in her situation, eating in Harvard’s dining halls can be a daily struggle.

“I heard from students who were basically so distraught that they were desperately seeking for ways to get off the meal plan, students who had decided that the safest way for them to exist on campus is to eat hardboiled eggs and bananas for every meal, students who were taking time off because they’ve been exposed to their allergen so many times,” she said.

“I feel like the safest option for anyone who has a severe food allergy is to just prepare your own food, but here that’s not really feasible,” Manning said.

Martin wrote that HUDS will only consider a waiver of students’ meal plans after they exhaust all “reasonable efforts” to accommodate dietary restrictions for those undergraduates.

“Dining is a central component of College undergraduate life,” she wrote.

Despite some persistent challenges, several students with allergies said the AEO has improved over their time at the College.

Manning said her experience with the AEO and dining has improved as a sophomore. She now has access to a nutritionist and dietician, as well as a gluten-free toaster, microwave, and fridge in Adams House stocked with speciality items.

She added that her dining staff is transitioning to gluten-free soy sauce so that she can partake in Asian dishes.

Jordan said that her current AEO accommodation allows her to request speciality products and items for personal use. She added that she thinks proper accommodations are important because of the role dining plays in students’ lives.

“I think dining is so essential,” Jordan said. “If you do it three times a day and if you can’t feel safe and comfortable, it really is going to be detrimental to your student life here and your level of happiness on campus.”

juliet.isselbacher@thecrimson.com amanda.su@thecrimson.com

DIVEST FROM PAGE 1

HMS Faculty Vote to Divest

is the latest among multiple recent victories for advocates of their ictories for advocates of their cause.

“Their overwhelming passage of a resolution calling for divestment and declaration of a climate emergency, which is yet another accomplishment of one

Caren G. Solomon ’81 HMS Assistant Professor

of the largest faculty activism movements in university history, sends a clear message to university administration that it’s time for real climate action,” the press release reads.

In comments before the vote, Medical School assistant professor Caren G. Solomon ’84 — who co-chairs the Council’s newly minted subcommittee on climate change — said it was particularly important for faculty from the school to weigh in on divestment because of its potential health harms.

“As physicians and scientists at the Medical School, we feel we have a responsibility to protect health,” Solomon said.

The T closes. We don’t. Breaking news, 24/7.