20 minute read

Editorial

THE CRIMSON EDITORIAL BOARD

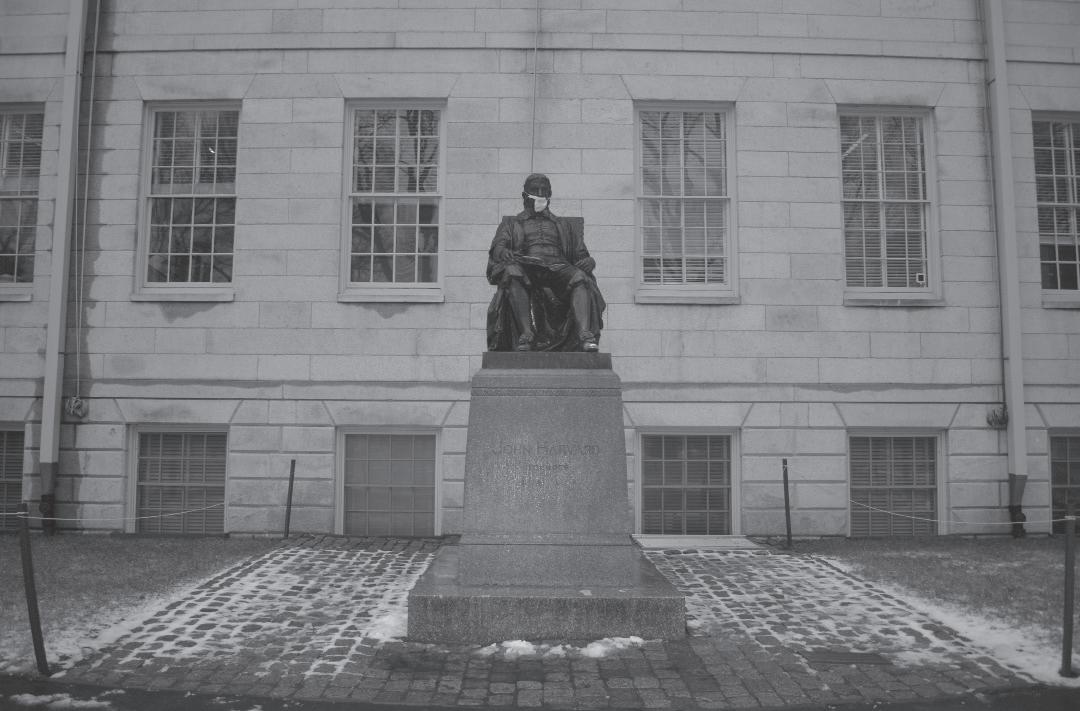

Putting Harvard’s Rent Increase in Context

Last week, Harvard University Housing announced rent increases for University-owned apartments in the 2020-21 academic year averaging one percent but up to two percent in some cases, on a unit-by-unit basis. The University reached this conclusion after a private consultant revised “market rents” for a number of apartments in Cambridge and surrounding areas.

We are conflicted about this increase. The move has drawn criticism from some graduate students who feel that the increased price tag will put University-owned housing out of reach. We empathize deeply with the students who feel that the institution they give so much of their time and effort to, at very low wages, is exploiting them for a free-market price.

All of their voices matter to us. And we continue to believe that graduate student stipends should be indexed to the

cost of living.

We must, however, simultaneously recognize that Harvard can only provide 50 percent of graduate students with housing. Not sticking to a market price would force the University to decide which half of the students should receive housing that is below market price and which half should not. Such a conundrum would be an equally, if not more troubling, ethical strain.

Still, further context is necessary. Harvard’s student housing does not operate in a vacuum. And though Harvard may seek to peg its rent rates to market prices, it is critical to note that Harvard’s expansive housing system has an outsized impact on the market itself. We should not forget that Harvard continues to have a direct impact on the ability of Cambridge residents to access affordable housing themselves, a problem that has preoccupied the city of Cambridge in the past year.

In an enlightening 2018 report, the Harvard College Open Data Project shows the extent to which the expansion of Harvard in recent years has gone hand in hand with the marginalization and reduction of local communities and in particular communities of color. Harvard, which owned nearly 10 percent of the land in Cambridge and nearly six percent of the land in Allston as of 2018, has seen its landholdings grow by over two and a half times since 2000. At the same time, in the ten years prior to 2018, Cambridge had one of the highest rates of home appreciation in the country, growing at an annual rate of 4.98 percent.

Still more startling, however, is that, controlling for relevant externalities, as Harvard’s endowment and landholdings have grown, the population of black and low-income residents of Cambridge has declined.

While Harvard last year pledged $20 million to support affordable housing

in the Greater Boston area, its gentrifying influence on Cambridge continues to concern us and, no doubt, the community bearing the brunt of the effects.

None of our concerns about Harvard’s adverse effects on its neighbors is meant to downplay the challenges that graduate students face or the extent to which the University’s financial prerogatives seem to be pitted against its oft-overlapping student and labor bodies.

Still, we hope that our internal debates at Harvard — especially those that deal with issues of equity, land use, community impact, diversity and inclusion, and livelihood — are thoroughly contextualized within the broader issues that affect Cambridge and all its inhabitants.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Submit an Op-Ed Today!

The Crimson @thecrimson

Update Available: Rethink Tech in Class OP-ED

The email from former U.N. Ambassador Samantha Power came into my inbox at 8:09 p.m. “Hi Kaivan - please don’t be on your phone in class - it is super distracting to your classmates, your profs, and — above all — to you! really important. Thanks!” I was in DPI 535: “Making Change When Change is Hard,” a Harvard Kennedy School course the Ambassador was teaching with her husband, famed legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein ’75. I was embarrassed, as the class had a no technology policy. I responded immediately, apologizing, assuring Ambassador Power that it wouldn’t happen again, and noting that just five minutes before class, then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions had resigned — a significant moment for anyone focused on change-making and the fight for justice.

Last week I was reminded of that email, in the first session of my Constitutional Law course, when our professor noted that she bans the use of electronics in class, citing “the pedagogy.” The professor told us how exciting the course would be this semester given the relevance of the ongoing impeachment hearings — and encouraged us to keep up with the news. Ironically, impeachment proceedings were literally ongoing this week, including during our 1-3 p.m. class timeslot.

As an online influencer in the progressive political space, I volunteer my time to help the Democratic National Convention, leading presidential candiBy KAIVAN K. SHROFF

dates, and others amplify key messages surrounding the Trump administration in real-time. Harvard Law professors, politicians, journalists, and celebrities engage with my content directly.

As a student at the Kennedy School and the Law School, experiencing the first impeachment of my adult life in this participatory way is a rare and educational opportunity. While it’s important to pay attention in class, spending five minutes of a two-hour-long session reviewing and responding to highlights of the hearings not only allows me to make important connections that will serve me in my legal career (something the Law School should support), but it also allows me to consider the ideas we are learning in a course such as Constitutional Law against an urgent real-world backdrop.

These anti-technology classroom policies are not unique cases. At my MBA program at the Yale School of Management, at the Harvard Kennedy School, and now at Harvard Law School, I’ve been banned from using any technology in many classes, even to take notes. It’s not just a huge disadvantage for someone with illegible handwriting. It’s infantilizing and counterproductive.

It’s true — I made a choice to be a student, and some could argue if I wanted to keep pace with the real world, I should have chosen to work instead. However, this logic is flawed because it undervalues the powerful potential of digital access in the classroom. The first, which I described above, is the discretion that technology affords ambitious, busy multi-taskers to attend to occasional external urgent matters — personal or professional — while still being present and learning in class.

There are also ways technology amplifies even the internal procedures and substance of classes. Allowing students to use technology in the classroom as they would in reality not only creates more time for critical discussion, but greatly expands the level of information and accuracy that can be brought into those discussions.

Students and professors won’t spend five minutes searching page by page for that specific Justice Elena Kagan reference in a 100-page Supreme Court opinion — someone will ⌘F the key phrase and the class will move on with the conversation.

A loosely remembered relevant source no longer stays on the tip of the tongue, but is confirmed with quick research and shared to enrich the class discussion. Foolish questions neither go unanswered, nor do they waste valuable class time — a win-win for everyone paying thousands of dollars for a single course.

Perhaps a more widely accepted argument is that banning technology forces students to learn in an antediluvian way. This outdated learning mode will never mirror the practice mode of the digital age. We won’t memorize the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure — we’ll Google them. We won’t write out Bayes’ Theorem from memory and “plug and chug”

— the process will be automated.

I’ve already experienced this generational shift. When I was in elementary school, cursive was being phased out. In undergrad, I took notes exclusively on my laptop.

I’m used to a multi-sensory learning environment of PowerPoint slides and online in-class polls that enhance discussions. That’s the future of education. In a world where all information is at our fingertips, application beats memorization every time.

I’m not necessarily surprised that graduate schools are slow to adjust to this tech-friendly future, but I was shocked that many of my peers are too. In my MBA program, many of my classmates, roughly 28 years old on average, were supportive of laptops being banned. They cited the same reasons as Ambassador Power — they were “distracted.” Having come of age in an era of immersive tech, I couldn’t imagine people with the lofty goals of my business school peers succeeding if they were so readily thrown off by a dimly lit screen and some low-decibel typing in the row in front of them.

We are adults, in our twenties, at an elite graduate school program, paying for education — it’s our time. To be regulated on our access to technology, including to the outside world, is reductive and juvenile. At the risk of sounding crass, I was responsible and focused enough to get into Harvard — trust me to make the right choices for my own education.

COLUMN

Education or Indigenous Erasure? Gabrielle T. Langkilde PASEFIKA PRESENCE

Icome from a lineage of geniuses.

My Samoan ancestors were so intelligent that they figured out how to sail across the Pacific using only the stars as their guide. Can you imagine that? People nowadays can barely get from point A to point B without Google Maps dictating each and every step that they’re supposed to take.

The genius of my Samoan ancestors is still evident in the elders and the youth of my Samoan community.

My cousins and I sit on the floor of the faleo’o and absorb the wisdom passed onto us by our grandfather, as he practices the sacred tradition of oral history and storytelling — tracing our family tree generations back and recounting memories that are not even his own.

When it comes time to practice and perform the traditional dances of the siva, sasa, and

fa’ataupati, the village youth perfect each careful movement with ease, naturally remaining in sync with each other to every beat of the pate. Though I come from a lineage and community of geniuses, this secret was kept from me.

In school, they did not teach me about the ingenuity of my Polynesian ancestors and their ancient art of navigation. Instead, they taught about great explorers like Christopher Columbus who sailed to what is now the Americas but initially thought he was in the East Indies.

Oral history and storytelling was merely a fun hobby because my school taught me that in order to be considered valid and sophisticated storytelling had to follow a rigid five-paragraph structure with advanced English vocabulary.

And with all of the stereotypes about our people as nothing more than “dumb jocks” because of our statistically low SAT/ACT scores but statistically high probability of making it into the NFL, I never considered the physically instinctive synchronization with my peers in our traditional dances as a form of intelligence.

The American school system, curriculum, and methodologies for measuring intelligence do not capture the genius of my community. Instead, they completely erase it and brainwash us into thinking that there exists only one way of knowing. American primary, secondary, and higher education systems are some of the strongest instruments of colonial domination to suppress indigenous ways of knowing.

American-style schools distort or more often than not completely refuse to teach our histories. This is evident in that history textbooks mention indigenous people as being “discovered” or that elite universities such as Harvard refuse to institute ethnic studies departments.

Additionally, the American education system’s measurements for intelligence rely on so-called “objective” tests that disadvantage students whose first language is not English and whose imaginations cannot be contained by rigid pro

cesses taught in the classroom. I realize the privilege and hypocrisy from which I speak, being a student at Harvard — the ivory tower of prestige and white-washed education.

Every time I go home, it saddens me to see my own community put me on a pedestal because of my acceptance into this institution. The romanticization of Western education only further devalues our own ways of knowing and reifies whitewashed education systems.

As my senior year approaches and I start thinking about my senior thesis, I continue to struggle with the idea that I must follow specific, concentration-approved methodologies and processes in order to produce valid knowledge about my own community.

Is this not the ultimate betrayal of my community and my ingenious ancestors that came before me? Some say that my presence at an institution such as this is a positive sign of progress and increase of Pacific Islander representation on campus. But if that is the case, why do I feel like my presence here only reaffirms the erasure of my people?

I understand that sometimes an education is the best route, both for personal upward mobility and for greater representation and visibility of a community. But the best option for my community, as well as other indigenous communities, should not be something that simultaneously erases it.

Datamatch Growing, Now Matchmakes at 26 Schools

By FIONA K. BRENNAN CRIMSON STAFF WRITER

Datamatch — a free matchmaking service run by Harvard students — doubled in size this year, and is scheduled to open at 12:01 a.m. on Friday morning at colleges across the United States and Canada.

Datamatch participants answer an online survey, and a “top secret” algorithm provides them with matches on the morning of Valentine’s Day. Unique to Harvard’s Datamatch is an option for paired students to get free food from a local restaurant. This year, several restaurants in Harvard Square — including BerryLine, Black Sheep Bagel, Amorino, and the recently opened Kung Fu Tea — have partnered with Datamatch to offer free food to paired students.

The matchmaking service was started by Harvard students in 1994 and — except for a pause in 1997 — has served Harvard students every year since then.

In 2018, Datamatch expanded to three additional schools, and in 2019, Datamatch became available at 13 schools. This year, the service will be offered at 26 schools — and make its international debut at McGill University. According to Theodore T. Liu ’20, one of the presidents — or “Supreme Cupids” — of Datamatch, other schools assemble their own small Datamatch teams so they can tailor the survey toward their colleges.

“We usually have around two to five people at each school that’s helping out both with writing questions that are kind of specific to the school and the inside jokes — they know the culture of the school — as well as kind of being that publicity person over there,” Liu, a former Crimson Technology chair, said.

Madison I. Richmond, a sophomore at New York University, said in an interview that she saw Datamatch on a friend’s social media, and discovered — a mere four days before this year’s launch — that NYU was not one of the schools that offered the matching survey. “I went on the website, and I found the emails, and I just kind of typed in all caps: WE WANT DATAMATCH AT NYU,” Richmond said.

In just three days, she and one other student put together NYU-specific survey questions just in time for this year’s launch.

“For me it was really about the fun of it, kind of the jokes, the buzz, bringing something

MADISON A. SHIRAZI—CRIMSON DESIGNER

new,” Richmond said. “I think it’s really awesome the way that technology can connect people on our campus, especially because NYU is so big and it doesn’t really have a campus.”

Though NYU only joined Datamatch a few days ago, Liu and the other “Supreme Cupid,” Ryan Y. Lee ’20, said that the Harvard team has been meeting since October.

“It’s always a full school year process. Even in September we’re already trying to form teams and get the word out about Datamatch,” Lee said.

The five Datamatch teams — web, algorithm, design, stats, and business — each focus on a different component of the project. On Valentine’s Day, when Datamatch participants are given their results, this year’s Cupids conclude months of work on the project — which saw its biggest expansion to date. “Across other schools, we do want to provide that same excitement and joy that we’ve been able to capture here for the past 25 plus years,” Lee said. “Just kind of get them in on the fun.”

fiona.brennan@thecrimson.com

BOARD FROM PAGE 1 A Look Back at Previous Board of Overseers Campaigns

their own Board of Overseers tickets in the 1980s and 2016, respectively.

Organizers for these groups, however, faced difficulties getting their candidates on the ballot — a challenge that members of Harvard Forward said they are facing today.

STRATEGIC CAMPAIGN

Beginning in 1986, the Harvard-Radcliffe Alumni Against Apartheid group, or the HRAAA, nominated candidates for the Board of Overseers with the goal of electing overseers who would encourage the University to end South African-related investments. Their campaign endorsed candidates for more than five different election cycles. The group succeeded in electing four of its candidates to the Board of Overseers: former Crimson president and current professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin Gay W. Seidman ’78, current Duke University professor emiritus Peter H. Wood ’64, former legal counsel to the House Energy and Commerce Committee Consuela M. Washington, and then-South African Archbishop Desmond M. Tutu. Donald M. Solomon, the former executive director of HRAAA, said that the nominating policy changed after the first election the group participated in.

“After the first election — which we ran petition candidates — I do remember Harvard changed the requirements and made it more difficult to get candidates on the ballot,” Solomon said.

He said that though he could not recall the exact changes, HRAAA had to work harder to get people on the ballot.

“At that time, we didn’t have online organizing opportunities,” Solomon said. “Whatever we did was mostly through direct mail and that made it expensive to run any sort of petitioning campaign.”

In 1989, Tutu won a seat on the Board of Overseers after petitioning for his nomination. Tutu was a longtime critic of the University’s investment policies in South Africa, and in 1984, he urged Harvard to divest from South Africa-related investments.

In 1991, to make its slate of candidates more competitive and condense its pool of endorsements, the HRAAA only nominated three candidates for the election. Among the candidates HRAA nominated in 1991 was former U.S. President Barack Obama, a fourth-year Harvard Law School student at the time.

“Desmond Tutu was — I think — the most successful [election],” Solomon said. “I think our feeling was that we probably couldn’t duplicate that in terms of having a recognizable big name. Obviously, we knew Barack Obama was a talented person but we didn’t anticipate that he’d become President.”

GOING DIGITAL 2016 brought a controversial campaign and further changes to the eligibility requirements of candidates running for the Board of Overseers.

That spring, a contentious ticket called “Free Harvard, Fair Harvard” – which included former U.S. presidential candidate Ralph Nader – ran for the Board on two central platforms: terminate undergraduate tuition, and scrutinize Harvard’s admissions policy, which the group contended was discriminatory to Asian Americans and antithetical to diversity.

The group also called on Harvard to make more data public about the processes by which the College admits students.

A group of nearly 500 alumni formed to oppose “Free Harvard, Fair Harvard.” The group, called “Coalition for a Diverse Harvard,” denounced the proposals by the campaign.

Former University President Drew G. Faust criticized “Free Harvard, Fair Harvard’s” platform in a 2016 interview with The Crimson, during which she denounced the idea that eliminating the University’s tuition would make Harvard more accessible to students.

After the controversial ticket in 2016, the University increased the number of signatures required to qualify a petition candidate by more than tenfold. The policies increased the number of requisite signatures from 201 to nearly 3,000 — approximately one percent of the eligible voting population. The increase was adopted because the necessary number of signatures required to nominate candidates had not changed significantly in over a century, according to a 2016 statement from the University.

“This increase was adopted in view of such factors as the magnitude of alumni support considered appropriate to qualify for the ballot; the fact that in recent years the number of required signatures—just over 200–has been barely more than what was required a century ago, when there were around 20,000 alumni eligible to vote,” the announcement reads.

With the increase in the required number of signatures, the University changed the voting process itself by transitioning to a secure online system to vote for candidates instead of having alumni submit official watermarked forms.

Kenji Yoshino ’91, who served as the president of the Board of Overseers for 2016-2017, said in an announcement at the time that the Board was pleased to move its voting process online. “We’re pleased to move to online voting, which alumni around the world have asked us to adopt,” Yoshino said in the announcement. “We will make this change as soon as we can put a secure and reliable system in place.”

University spokesperson Christopher M. Hennessy wrote in an email Thursday that the school started online voting “to provide greater and easier access for more alumni around the world to participate in the process.”

LOOKING FORWARD After past insurgent Board of Overseers campaigns drove up nominating thresholds, Harvard Forward faced its own challenges to get its candidates on the ballot.

Each of Harvard Forward’s candidates received more one thousand signatures above the requisite number, according to a press release from the group last week.

“The final signature count, pending verification from the Office of the Governing Boards, consists of nearly 1,400 online signers and more than 3,400 unique in-person signers,” the press release stated. “As each candidate must be nominated individually, the campaign ultimately collected over 20,000 separate signatures.”

Harvard Forward’s Campaign Manager Danielle O. Strasburger ’18 wrote in a press release that the milestone was reached despite alumni difficulty with the online nomination process.

“We reached this milestone despite hundreds of alumni encountering real difficulties with Harvard’s complex online nomination process,” Strasburger wrote in the press release. “By our estimates, almost 1,000 additional alumni were unable to submit their nominations because of the poor design of the system.”

The University is dedicated to assisting the school’s alumni network, Hennessy wrote in an email Thursday.

Eligible voters could submit their signatures either through the online form or a paper document. Strasburger wrote in a press release that Harvard Forward organizers directed their efforts to acquire more paper petitions from alumni.

“Of course, switching our focus toward using paper petitions required that we build and mobilize a large network of volunteers and supporters around the world,” Strasburger wrote. “They will continue to be the driving force of this campaign as we prepare for the coming election.”

Harvard has received the nomination forms, Hennessy confirmed Saturday. The University will now verify and validate petition submissions over the next two weeks. While waiting for the official confirmation for the group’s petition, Harvard Forward scheduled strategy calls to discuss election and publicity strategies, according to a Thursday email sent to supporters.

michelle.kurilla@thecrimson.com ruoqi.zhang@thecrimson.com