3 minute read

STRIVING FOR A DREAM

BY DAVID ROTHENBERG Fortune Founder

After my first visit to a jail, which was Rikers Island in December 1966, I commented, “This seems to be an exercise in institutional futility.” Nothing there seemed to prepare those inside for a return home.

I didn’t know that would begin more than a half-century of visiting jails and prisons across the country, including being an observer inside the yard at Attica during the 1971 uprising, teaching a class in Rahway State Prison in New Jersey, meeting with survivors in solitary in a New Mexico state prison after a brutal riot, running groups in the Brooklyn House of Detention, and hundreds of talks, visits and tours within the walls in Montana, Texas, Florida, Pennsylvania, Colorado, New York, Delaware, New Jersey and on and on.

My initial reaction to Rikers Island was continually confirmed. There were isolated programs, but the totality of the prison experience indicated that incarcerated men and women, first and always, had to learn how to survive in the humdrum, by-thenumbers environment, which also promised unanticipated violence. In short, prison survival has nothing to do with street survival. How people fare upon release seemed to be, and continues to be, an exercise in futility in our archaic and life-destroying prison system.

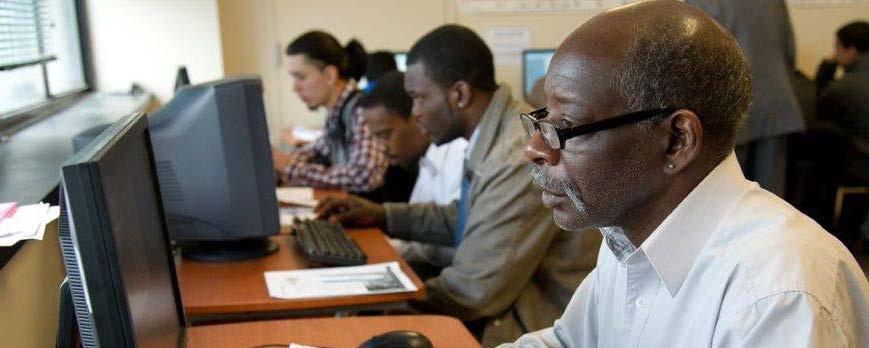

I am of the opinion that our punishment factories could serve the greater society with realistic vocational training programs, utilizing community instructors in various fields. Almost every person currently locked up will be job hunting upon release. Along with safe housing, it is a survival priority and an antidote to crime.

By the dozens, each week at The Fortune Society and similar programs around the city and nation, returning citizens arrive with hope and dreams. Few have immediate employable skills or work experience. They need to be more experienced with job interviews or preparing a resume. There are numerous obstacles, so Fortune offers a few weeks of preparation for reality to join the dreams. All of this could have and should have happened before release when prisons have individuals 24/7.

And yet, miracles do occur.

One of the wonderous aspects of the human spirit is what we witness, almost daily, men and women overcoming roadblocks and political restrictions. They are the strivers who realize their dreams.

Here are some of the stories:

Fran O’Leary, one of the first women to come to Fortune, was invited to speak at a national conference in Hawaii. She impressed sufficiently to be offered a job running a program for young women in trouble. Fran lived and worked in Hawaii for two decades before retirement.

Charlie McGregor, whose dynamic presentation at speaking engagements reflecting on his 28 years in prison, led to a film offer and a career in movies and television. Most memorable are his roles as Fat Freddy in Shaft and in Mel Brooks’s Blazing Saddles. Charlie called me a few years back and said he could never have imagined the second half of his life could have been the total opposite of the first half, and he said, “It all began at Fortune.”

Let’s add them up: Richard Louis is a college professor; Stanley Richards was named Deputy Commissioner of Corrections in New York City (a historic first, but blessedly he’s now back at Fortune); Alex Mitchell is a lobbyist in Albany; George Freeman heads a church in Seattle, Washington; Mel Rivers departed Fortune to be head of security at an NYC hospital; Kenny Jackson was named a prison ombudsman reporting directly to then-Governor Mario Cuomo; Vinnie Defrancesco was the purchaser and manager of a major restaurant; Mikel Green Grande is a community outreach coordinator.

Other jobs held by people coming through Fortune include a health counselor, landscaper, doorman, taxi driver, theatre manager, plumber, chef, nurse, computer analyst, art teacher and more than half the staff at The Fortune Society are formerly incarcerated. The list is endless and added to daily.

One of the most dramatic and historic journeys is that of Walter Strauss, whom I first met when he made his second state bid in Rahway, a New Jersey state medium-security prison. When he was released, he worked part-time at Fortune while attending college. When he graduated, he told me he was considering law school. I was concerned that he might find a negative response from the Bar’s Ethics Committee, and he told me, “I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it.”

Walter graduated from Rutgers Law School and passed the Ethics Committee’s challenge. I couldn’t have been prouder of my friend as he diligently performed his duties as a lawyer.

Ten years after starting his law career, Walter called me one day and invited me to attend a ceremony at a downtown Manhattan courtroom. The following day, Walter Strauss was sworn in as a judge, the first formerly incarcerated man to achieve such a title.

Now retired, Judge Strauss visits Fortune and proudly tells his story to men and women who have come through our doors just as he did.

I look at the new arrivals at Fortune, survivors of our shameful gulags, and I believe everyone has the potential to be:

• An inspired national leader like Malcolm X

• A movie star like Charles Dutton

• A NY State Assemblyman like Eddie Gibbs

• Or a judge like Walter Strauss

All were formerly incarcerated.