14 minute read

Dr.Hoskin&Dr.Blair

Can you summarize your work and the mission behind it?

Click for Dr. Rhea Ashley Hoskin's Website

Advertisement

Dr. Hoskin: My work broadly focuses on femininity, especially regarding gender-based violence, as well as sexual and gender diversity. In my undergrad, I recognized an apparent gap in how feminist and sociological theories attended to femininity; specifically, this gap overlooked femme identities and experiences and how femininity was more than exclusively a tool of the patriarchy used to oppress women. The mission behind my work has always been to remedy this gap, bring femme voices, experiences, and insights to the “academic table,” and inspire people to think in more complex and intersectional ways about femininity...from a femme perspective!

Click for Dr. Hoskin's FEMME THEORY Page

Dr. Blair: I am a social psychologist, primarily focusing on close relationships In all of my research, I use LGBTQ-inclusive research methods, meaning that when I design a study about affection in relationships, I’m not only interested in heterosexual relationships, but I am also interested in how affection functions across all types of relationships - such as same-sex and gender diverse relationships One key area I’ve studied extensively involves understanding the role of social support and approval for our relationships - are our relationships happier and healthier when our friends and family support who we pick as partners? (short answer: yes!) Unfortunately, same-sex and gender-diverse relationships still often lack support from friends, family - and even society - so my research also includes the study of stigma, discrimination, prejudice, and hate crimes. Femmephobia is a common prejudice that exists both within and outside of LGBTQ+ communities, and thus this is where my work converges with that of Dr. Hoskin’s - or Rhea Ashley… but I call her Ashley. You can learn more about my research on my Psychology Today Blog or my website, where most of my articles are freely available to download and read.

In your opinion, what does society most often get wrong about femininity?

Dr. Hoskin: There are so many things that society gets wrong about femininity. It’s hard to pick just one. From a femme perspective, we can boil down what society gets wrong about femininity into two things: first, its value (i e , that it’s worthless, unimportant, or somehow “subordinate” to masculinity), and second, its purpose (i e , that it is either a set of traits that cisgender heterosexual women use to attract men or a tool of the patriarchy) These assumptions feed into various types of gender-based violence, harassment, and prejudice. What society “gets wrong ” about femininity not only contributes to pressing issues of violence but is also not an accurate reflection of the world. As a femme and femininity researcher who has spoken to people of all identities about their femininity for nearly two decades, when society talks about femininity in this reductive way, it feels to me like the equivalent of someone trying to convince me the world is in black and white despite existing in a kaleidoscope It’s just not true

Femininity is worthy and valuable, and it carries so much more purpose beyond a sexist gender role enforced upon people assigned female at birth

Dr. Blair: In simplest terms, I think society tends to erroneously believe that femininity stands in for “ women. ” Thus, we expect women to be feminine, and only women should express feminine traits. But not all women are feminine, which doesn’t make an individual any less of a woman. Women can be masculine, androgynous, feminine, or any combination of those three expressions On the flip slide, this also means that anyone can be feminine and that being both a man and feminine doesn’t make someone any less of a man

Much of what we label as “masculine” or “feminine” today comes from assessing the ‘most common interests’ among men and women in the early 1900s - I’m not sure we should be so surprised when people don’t fit so neatly into those same interests today - in fact, even in the early 1900s scholars observed that people varied greatly in how well they ‘conformed’ to the ‘ norms ’ of their sex when it came to interests and traits.

What is your relationship with feminine expression?

Dr. Hoskin: I was raised by a second-generation feminist, who dressed me in my brother’s handme-downs. At a very young age, I made it known that I preferred frilly and feminine dresses over my brother’s (or other masculine) clothes, and my mother nurtured this creative femininity and allowed it to grow and transform as I wished. As I talk about in an article in the Journal of Lesbian Studies, the onset of puberty changed how my femininity was received by my surrounding world: from something creative, expressive, and quirky to something seen as attention-seeking and invested in boys' approval. This assumption couldn’t be further from the truth.

Flash forward to my undergraduate degree, where I majored in Gender Studies and Sociology, and I found myself grappling with some of those assumptions in light of my burgeoning sexuality If being a lesbian meant being masculine (or not being feminine), and I loved being feminine, then maybe I was not a lesbian I was also specifically attracted to masculine women, which complicated things further: some saw this as further evidence that I was really “straight” because masculinity is assumed to be an expression only for men – but, as Karen mentioned, women (whether they are cisgender or transgender) can be masculine, androgynous or feminine In short, my gender expression and sexuality seemed “at odds”; at least, that was the message I received from society I then discovered the narrative works of femme authors who helped me to understand myself and gave me words to describe my relationship to femininity: femme!

To this day, it’s striking that someone in Gender Studies would grapple with these thoughts. To me, it’s a great example of the outcome of excluding femme voices from theory and academia. Even in Gender Studies and feminist theory, we have erased feminine diversity and largely resorted to the same assumptions made by broader society.

Dr. Blair: I had the opposite childhood experience - my mom loved buying me lovely dresses and outfits. But by grade two or so, we had pretty clearly worked out that I wasn’t into dresses, and I had a set of matching sweatsuits that came in different colours, and I would cycle through those each day of the week! I was your typical tomboy and didn’t like frilly things, lace, dresses, or uncomfortable shoes I went to a high school where girls were supposed to wear a kilt as part of their formal uniform each Monday - but I never followed that rule and wore pants all but perhaps three days of the five years I was there One of the three times I wore the kilt was because someone else dared me to, and I made $50 out of the deal! Perhaps that alone says something about society’s expectations for women and femininity - my avoidance of it was worthy of someone spending $50 to dare me to “conform ”

How do you determine your research topics?

Dr. Hoskin & Dr. Blair: We tend to determine research topics mainly by observing the world around us and reading the literature As researchers, we observe the world shaped by who we are and our areas of academic expertise. When we find something perplexing, we turn to the existing scholarly literature to see what other scholars have done, what gaps remain, or what oversights or biases exist in the research. We then develop studies to move the research forward, remedy those gaps, or address biases in previous works.

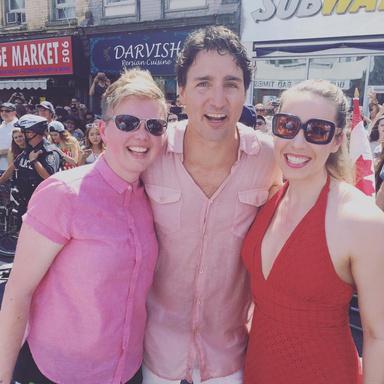

Dr. Blair and Dr. Hoskin with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau

Dr. Hoskin: My research program has always been close to my heart and experiences When I turned to the literature, there was a shortage of research on femme and femininities, and what did exist was very reductive, stereotypical, and perpetuated many femmephobic assumptions. Thus, it has been quite a privilege to be able to spend my career focused on filling those gaps and conducting research with amazing femme participants.

What has been your biggest challenge researching and writing about femmephobia?

Dr. Hoskin: I think the main challenges I face with researching femmephobia are helping people to understand its relationship to misogyny and sexism alongside the general treatment of the field of femininities. It can be hard to communicate the distinctions between misogyny/sexism (prejudice toward women) and femmephobia (prejudice toward femininity, across gender identity) to journalists who only want simple and concise soundbites and audiences that aren’t particularly interested in getting into the nuance. I am always cautious that how I approach femmephobia in my work and interviews does not overshadow misogyny or remove the importance of addressing misogyny. Femmephobia is not a new buzzword we should pay attention to instead of misogyny. Femmephobia is a facet that we must consider alongside other forms of gender-based oppression.

Secondly, the field of femininities is consistently disparaged and seen as unimportant In academia, we call this an ‘epistemic injustice,’ meaning that scholars do not produce or value knowledge on all topics equally: some knowledge is silenced, dismissed, excluded, or seen as unimportant, and this process is not “isolated”; it’s systematic Further to this epistemic injustice, as many other marginalized scholars know, it’s hard to research a specific form of prejudice when you are the target of that very same prejudice In the case of femmephobia, society’s general assumption that it is natural or normal to denigrate and devalue femininity makes defending the study of femmephobia even more challenging. I think Julia Serano said it best when she noted that while discrimination based on being a woman is generally frowned upon or not openly condoned (that’s not to say it doesn't happen!), discrimination based on femininity remains fair game. It’s hard to move a field forward when the epistemic injustices and prejudice it faces are still considered “fair game ” and a heavy burden for scholars whose intellectual, professional, and personal identities are in the crosshairs.

Dr. Blair: I have mostly just been along for the ride, which has enriched my research and teaching experiences I think the biggest challenge for me has been watching the slow pace at which academia seems to be realizing the contribution of femininities scholarship and the continued uphill battle of having this area of research seen as legitimate when it ‘stands on its own. ’ What I mean by that is that it is generally acceptable to sometimes study femininity or to incorporate the concept tangentially into a seemingly ‘ more important’ area of research. However, wholly focusing on femininity is not seen as a needed or valuable contribution. Several journals focus on the study of masculinity in various domains, but not a single journal focused on femininity. What is striking is that the concepts, theories, and research resonate with members of the public - of all different ages, walks of life, genders, and sexualities - but as we say in one of our articles, something has held the field of femininities in this constant state of emergence, never entirely seeming to ‘mature’ into a respected area of inquiry – But is that a surprise when we see femininity as a marker of immaturity and incompetence? The most valuable currency in science and academia is expertise; if society inherently views expertise as a masculine trait, then being an ‘expert on femininity’ will remain an oxymoron

What is something people would be surprised to learn about you?

Dr. Hoskin: Hmmm, that’s a hard one! Maybe that I love weightlifting and used to be a fitness instructor Of course, being a fitness instructor may not be surprising (unless you know what an introvert I am), given the stereotype of the perky feminine instructor, but people are often surprised that someone feminine loves to lift weights, build muscle, “bulk,” or have any visible muscle whatsoever. In part, it’s because we associate masculinity with strength and power and femininity with weakness and powerlessness. For example, many people often assume that Karen is the “strong one ” in our relationship simply because she is more masculine than me. I have also encountered people’s surprise over the assumed contradiction between my femininity and love of weight lifting (and muscles) as a fitness instructor and when I lift weights in the gym. I think my femininity seems to give (unauthorized) permission to men to comment on my form and weight selection. Then again, across domains, men feel entitled to weigh in on what women do with their bodies, whether they’re feminine or not!

Dr. Blair: Well, based on Ashley’s answer, they might be surprised to learn that I’m not very (physically) strong! Ashley does all the heavy lifting around here - and I’m quite happy with that arrangement!

Dr. Blair and Dr. Hoskin on their wedding day in 2015.

How did the two of you meet and what do you do for fun together?

Dr. Blair: We met while we were both graduate students at Queen’s University. Our first date was at a Starbucks near campus I brought my dog Miles, Ashley brought her dog Ellenore, and we sat on the patio talking Our conversation quickly turned to our respective research areas, and Ashley tried to explain her concept of femmephobia and femme theory to me. It mostly went over my head, but as the evening went on, I began to get research ideas. I remember drawing many weird Venn diagrams and trying to explain that we could measure the theories she was articulating. We ended up going to dinner and staying up all night talking. Miles peed all over her apartment - in at least 3 or 4 different places - yet she still invited us back the next day That was 12 years ago These days, we go to bed around 9 or 10 pm, but other than that, much of our life remains as it was on our first date: good food, good conversation, brainstorming new research, and continuing to encourage Miles to pee outside.

If you could plan a FEMME Pride event/march, what would it look like?

Dr. Blair: Ashley (Dr Hoskin) did this when she was an undergrad at Trent University She decorated a float and dressed as Lady Gaga

Dr. Hoskin: That’s right! I organized a “femme float” during my undergraduate degree at Trent University. I dressed up as Lady Gaga - other people dressed up as SuperGirl, HelloKitty, Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz, Cleopatra, Marilyn Monroe, Betty Page… whatever feminine icon inspired them. I created and handed out pamphlets to teach people about femme identities and experiences. The materials and language were a bit clunky by today’s standards, and I would approach the value of softness and vulnerability with a bit more nuance if I were to run a similar event today. I would also do a better job of teasing apart femmephobia and misogyny. Still, I look at the pamphlet and feel proud of the budding femme scholar who wanted to change the world!

I would love a re-do of this event: a femme float at Toronto Pride, where we disseminate educational material and resources on femme identities, experiences, and femmephobia After all, the LGBTQ+ community can also be quite femmephobic, and they only mimic or reflect a broader society that devalues and controls femininity To challenge femmephobia, we have to be able to name it, identify it, and begin to challenge our thinking – even within the LGBTQ+ community.