8 minute read

The Brutal Joy

Lecture Excerpts

By Justine A. Chambers

Beauty is not a luxury, rather it is a way of creating possibility in the space of enclosure, a radical act of subsistence, an embrace of our terribleness, a transfiguration of the given. It is a will to adorn, a proclivity for the baroque, and the love of too much.

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments

Beginnings

This story, this Brutal Joy, begins - for me with my grandmother, and her stories about dancing on Saturday nights at The Bronzeville Ballroom on the south side of Chicago in the 40s, 50s and 60s. I see her in my mind’s eye, elbows linked with her best friend Marie as they enter the ball room, turned out, and holding her beaded purse in her gloved hands.

I can see the two of them elegantly surveying the room, heads leaned into each other, neck’s long, clocking who's there and noting what folks are wearing. I see them glide over to a table, put down their purses and remove their gloves, because friends, they are about to shake a tailfeather.

My story continues with my Granny taking me to a jazz club in the 80s on a Saturday afternoon. It was a small room: filled with smoke caught in shards of light and the feeling of bodies listening. Cafe tables and chairs filled the room, and the floor was gritty. The musicians were close - close enough to touch and they held court in a corner of the room.

The intimacy of this space didn’t allow the audience to recede into the darkness. The collective movements of the room were never separate from the experience of the performance: clinking glasses communed with the drum kit, bodies bent and winced in the deliciousness of horn solos, and every head in the joint bobbed in unison. Everyone’s presence was felt. The room held measured stillness and calculated chaos. It was so quiet sometimes that I could feel the invisible, and so cacophonous at others it felt like my internal organs were in spasm. It was sublime.

The Brutal Joy is the final utterance in The Heirloom Suite; a series of performances that wield the materiality of Black Vernacular line dance and Black sartorial gesture as physical cogitation, reverie, and devotion to Black-living. The Brutal Joy is a scored improvisational performance for sound, light, and dance performed by Mauricio Pauly, James Proudfoot and myself with our dramaturg/outside eye Vanessa Kwan. The work is an antiphonal relational collaboration, an activation of The Electric Slide and Black dandyism to invoke the Black imaginary, and an embodied counter-archive — a reservoir for gestures, individual affective memories and under documented histories. A history that begins with the Middle Passage - the stage of the Atlantic slave trade. These social practices that emerge from that violence, persist as epistemologies, contemporary tools for self-determination, and reclamations of Black humanitarian value in a 400-year dialogue with colonialism. Dance and garments were a symbol of the bridge between slavery and emancipation. At inception and persisting in the present, Black dandyism and Black style are indications of social, political, cultural and economic change (Miller 8).

Change

All that you touch

You Change.

All that you Change

Changes you.

The only lasting truth is Change.

God is Change.

- Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower

The embodiment of change is required to imagine ourselves otherwise. The vernacular practices in my research, provide practical tools for actualizing change from within our own bodies in concert with our communities. Activating body sovereignty initiates a shift in perception, directs us towards what could be possible, and provokes it to arrive. Through style and dancing, we can practice change and see/feel ourselves beyond the unrelenting strain of being “perversely tied to the dehumanizing logics of white supremacy” (McKittrick, 3). This is the work of the counter archive through embodiment.

Archives

“What happens to our understanding of black humanity when our analytical frames do not emerge from a broad swathe of numbing racial violence but, instead, from multiple and untracked enunciations of black life?”

- Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science

The embodied archive is an imperative of Black life. Knowledge hierarchies and systemic notions of who and what has value have obstructed Black histories from freely unfurling beyond and below their colonial damage-centered narratives. In response, I feel called to archive and preserve Black life as complex, intimate, valuable, funky, nuanced, faceted, multiple, audacious, and private. Katherine McKittrick speaks to this when she says, “The story asks that we live with the difficult and frustrating ways of knowing differentially. (And some things we can keep to ourselves. They cannot have everything. Stop her autopsy.) They cannot have everything”.

Curator Denise Ryner writes, embodied archives “become counter-sites to institutions, departing from their conventional role of mapping out historical points in linear time and becoming, instead, tools of Black […] futurity around which anticolonial solidarity can be built and sovereignty reclaimed.” And so, I take up Christina Sharpe’s task to “function as a living library” — a present-future living memory to shirk the flattening of metaphors and tropes in order to “discredit(s) ethnic absolutism” (McKittrick, 5).

The embodied archive is implicitly housed within — and is living evidence of — social, historical, intellectual, conceptual, and theoretical frameworks. Black diasporic histories are held in the flesh and shared through flesh. They contain geographies, colonial fictions, individuals, collectives, methodologies, feelings, symbols and codes. Codes of sociality, codes for survival, and codes of belonging, Our archive must not be of a singular construction. Our embodied recordings are counter-archives — subjective, mutable, contingent, provisional, coherent, and most importantly exercises in futuring.

Black vernacular line dance and Black style vitalize the counter-archive by insisting upon and building space for individual presence; the feeling and articulation of self from within their forms and structures.

“Perhaps we can each make space in the places where language cannot travel, those corners where there is feeling only, and the sharp vivacity of memory thrives.”

- Legacy Russell

Black dance is never just dancing, it never sits alone. It is imbued with everyday living. Embedded in my dancing story is motown, disco, jazz, R&B, hip hop, blues, Stepping, the Roger Rabbit, the Cabbage Patch, MGM musicals, milk crates filled with records stacked in the hall closet, Ebony magazine on the coffee table, the smell of nail polish on Friday nights, braids, beads and barrettes, jars of Vaseline for faces, elbows and knees, getting greased up by my mother, watching the Twilight Zone while eavesdropping on kitchen table conversations not yet meant for my ears, warning glances and side eye, the “ain’t nothing but”, Reebok 54.11s, hot pink bridesmaids dresses with matching netted fascinators, lay-away, beaded purses, stockings hanging over shower rods, swagger, wigs in waiting on styrofoam heads on the bathroom window sill, “if you know, you know”, barbecue, overcooked collard greens sitting in a green/brown puddle of juice on a paper plate, German chocolate cake, a pot of frying oil on our stove as a permanent installation in our kitchen, jacks and double dutch. “You feel me? ” All of this coats the inside of the dance.

Feeling and articulation imbues and adheres to these social dances. They ‘counter-act,’ rewrite, and ‘animate over’ as a means to support the preservation, emergence, and continuation of the counter-archive. Individual and collective Black dancing bodies become scaffolds, memorials, and living, moving, breathing monuments from which Black histories can be re-cast through the flesh. From this inheritance of ‘doing,’ our bodies synchronously retain the latent and invite the incipient—our archive has been made and it is arriving right now. The Brutal Joy allows my archive to speak and act when, and as needed. It offers performance as a mode of creative archival access, while also proposing that if the work is a living library then, we must “see the pages formed as forms still forming” (Phanuel Antwi).

Devotion

This work is a devotional act that asks ‘the record’ to expansively include the complex singularity of experiences that constitute this Black life. This performance practice, re-centres Black vernacular practices and their organizing structures as ontology and epistemology in order to echo forward the possibility to incite change, to be irreducible, and to imagine freely. All of this in reverence for Black-living.

Justine A. Chambers is a dance artist and educator living and working on the unceded Coast Salish territories of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh Nations in Vancouver, Canada. Her practice is a collaboration with her Black matrilineal heritage, and extends from this continuum and its entanglements with Western contemporary dance and visual arts practices. At the centre of her practice is a question often posed by her grandmother: “You feel me?” Her research attends to individual and collective embodied archives, social choreographies of the everyday, and choreography and dance as otherwise ways of being in relation.

Chambers’ work has been hosted at galleries, festivals and theatres nationally and internationally. She is an Assistant Professor at the School for Contemporary Arts at SFU, and Associate Artist to The Dance Centre. Chambers is Max Tyler-Hite’s mother.

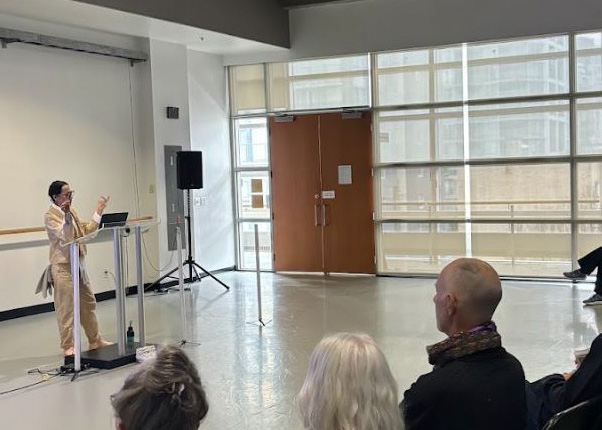

Title image credit: Justine A. Chambers in The Brutal Joy © Rachel Topham Photography