34 minute read

In the News

Pinewood Toronto Studios in October unveiled three new state-of-the-art sound stages, part of a $40-million expansion plan. The expansion project is part of ongoing efforts to establish a cultural hub for film, television and digital media in Toronto’s Port Lands. Pinewood Toronto Studios has developed a Film Studio District Evolution Plan, a blueprint for how the approximately 30 acres of land within the Film Studio District will act as a catalyst for investment and transform the area. The three new sound stages are 10,800 square feet each, and an additional 100,000 square feet of new office space is expected to be complete in 2015. In total, Pinewood Toronto Studios will feature almost 400,000 square feet of modern, purpose-built production facilities for film and television. Pinewood Toronto Studios is located just outside the downtown core in the Port Lands, an area along Toronto’s eastern waterfront that will soon experience major investment and revitalization. The studios will anchor an emerging waterfront neighbourhood, the Film Studio District.

New Sprinter Genny, EXO Camera Cart at PS Toronto

PS Toronto recently announced its custom-built generator unit is now available to service productions in Toronto. The low emissions Perkins Tier III 500 AMP generator is disguised inside a Sprinter Van, which measures less than 8’ in height and 19’ in length. Along with the power plant being green, the generator operates with very little noise at less than 50 dB at 50’. It also comes equipped with magnetic decal covers to place over the PS logos so that crews can place it in a scene to blend in as “just another delivery van.” PS also announced that it has added the EXO Electric Powered Camera Cart to its specialty equipment fleet. The unit is delivered with a full inventory of mounting and rigging hardware so it can be customized on set. The fully electric cart offers multiple configurations, including for Steadicam work, rigging remote heads and mounting multiple cameras and jib arms. It also features four-wheel drive, independent and airbag suspension.

New 800 W ARRI M8 Fixture Rounds Out HMI M-Series

ARRI early this fall unveiled the M8, the latest and smallest lighting fixture in ARRI’s M-Series of HMI lamp heads. Like the rest of the M-Series, the M8 is equipped with MAX Technology, a reflector design that unifies the advantages of a Fresnel and a PAR fixture. With the M8 at one end and the ARRIMAX 18/12 at the other, the M-Series is a comprehensive daylight toolset, comprising five lamp heads that between them offer a range of nine evenly-staggered wattage options from 800 W up to 18,000 W.

New 800 W ARRI M8 Fixture

Rounds Out HMI M-Series Courtesy of ARRI

New Sprinter Genny, EXO Camera Cart at

PS Toronto Courtesy of PS Toronto

yFy channel’s drama series Haven centres on a fictional town where people with supernatural afflictions, known as “troubles,” seek refuge. Each episode sees a new trouble realize itself – a character may be able to change the weather or poison all of the town’s food, for example – a premise that presents a new visual challenge each week, according to director of photography Eric Cayla csc, who has shot three seasons of the series. Cayla describes reading the script for one episode in which one of the characters has the power to cause anything that comes near him to implode, including people. “When you’re reading the script for that you say, ‘How are we going to do this?’” Cayla says. “Everybody is challenged, from the art department to the props. And for us, visually, how are we going to shoot it? They’re all unbelievable stories; the big challenge is to make it work and be believable. Also, we don’t have much time to prep and we don’t know months ahead what we’re going to face.”

Shot in Chester, Nova Scotia, with multiple directors, Haven is one of the few television series shooting in Canada being captured on film, and for Cayla the distinct texture and lighting that film produces is where the visual style of the show lies.

When he signed on to shoot the first season, Cayla found visual inspiration in the work of American painters Winslow Homer and Andre Wyeth. “Homer for his vivid, strong textures and contrasty images – he did a lot of paintings in Maine where the series is set – and Wyeth for his strong, neat composition, the way he places people. It really fits the world of Haven,” Cayla observes.

For a project with a supernatural premise, creating strong visuals seems to go a long way to suspending viewers’ disbelief, Cayla maintains. He and his team use tableau-style compositions, particularly in wide shots, and in closeups endow the characters with a mysticism by creating painterly images with soft light. Naturally, they put the picturesque Nova Scotia landscape at the forefront. “Part of the success of the show is the visuals,” Cayla says. “People really like watching it. We create a very painterly, mythical, beautiful place.”

Haven comprises many day-exterior scenes, playing out on beaches, rural streets, forests and fields, and that was one of the driving forces behind the decision to shoot on film. “Film captures natural light, in my mind, more organically, more naturally,” Cayla remarks. “It has a more earthy texture, whereas digital is very harsh. Film for me is more like oil painting and digital is more like hyperrealism paintings, and that doesn’t fit the story of Haven. I mean, we could make it work, but with film the texture is just there. It’s not as sharp, not as crisp, and the highlights are softer and more subtle. Now, we all know digital is fantastic in the dark, but since we’re outside a lot, we’re dealing with a lot of highlights and skies and water. It has a very nice soft response to that kind of light.” • see page 6

By Fanen Chiahemen

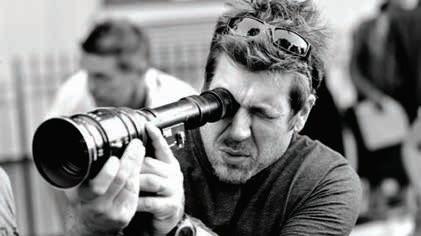

DP Eric Cayla csc

Eric Cayla csc’s Haven

Eddy McInnis: First AC

Winner: CSC Camera Assistant Award of Merit, 2013

What is unique for you about working on Haven?

It has to be that we’re still shooting 35 mm. Because I know how rare it is now to hear film run through the gate. It’s such a tangible thing. All that mechanical, tangible stuff is very much noticeable. It really sets it apart from other shows. A lot of us learned on film and went to the HD world, so it’s

see page 9

Above: Emily Rose and Colin Ferguson in a

scene from Season 4 of Haven.

Next page clockwise from top left: Lucas Bryant

(right) as Nathan, and Adam Copeland as Dwight star in Haven, filmed on Nova Scotia’s south shore. Eric Cayla csc in action on the set of Haven. Eric Balfour as Duke, and Emma Lahana as Jennifer in a scene from Haven Season 4, filmed on Nova Scotia’s south shore.

The show employs the Panavision Panaflex – three 2-perf bodies and one 3-perf – with Panavision primo lenses and zooms. “Panavision gives us a great deal,” Cayla notes. “And Kodak has great stocks, like 5219 500 tungsten and 5213 200 tungsten,” he adds.

Cayla also finds the workflow of film shooting suitable for him and the production. “It’s so fast it’s unbelievable,” he says. “Because you’re not trying to watch the monitors, you’re not dealing with a DI. You observe what’s in front of you, you light, you expose and you shoot. Some directors are surprised how fast it goes. But you’ve got to know film sensitivity because it’s a very instinctive way of shooting. You have to have good instincts when

CSC

Wisdom Lecture Series

By Professionals, For Professionals Guest Lecturer: Cinematographer, Luc Montpellier csc

Luc Montpellier is one of Canada’s most esteemed and prolific cinematographers. Known for his distinctive and creative use of light to give a project its visual language, Montpellier has over 54 credits as DOP, which range from theatrical feature releases, short films, television series and music videos. Montpellier’s long list of collaborations include auteur

Don’t miss this opportunity to learn by listening to Montpellier talk of his experiences as a top DOP while showing selected clips from some of his most notable films; (The Right Kind of Wrong), (Cottage Country), (Take This Waltz), (Away From Her), (Cairo Time), (Inescapable), (Poor Boy’s Game), (Saddest Music in the World), and (Cell 213).

A Q&A session with the audience will follow Montpellier’s presentation.

directors such as Sarah Polley (Away From Her, Take This Waltz), Ruba Nadda (Cairo Time, Inescapable), Clement Virgo (Poor Boy’s Game), and avant garde filmmakers Guy Maddin (Saddest Music in the World) and Michael Snow (Preludes). Montpellier’s DOP talents have garnered him Canadian Society of Cinematography and Genie awards, and the Haskell Wexler Award from the Woodstock Film Festival.

Wednesday, December 4, 2013, 7:00pm

Refreshments courtesy of:

Hosted by:

424 Adelaide Street East, Toronto

Moderator: Sarah Moffat, Associate csc Member

Seating is limited and priority will be given to participants who pre-register. Lecture begins at 7pm sharp. Tickets: CSC Members in good standing: Free (please bring membership card) Non Members: $10 (cash only) Students with ID: Free Registration: Please send your name and guest names to karenlongland@csc.ca Using subject line: Wisdom Lecture Series – Montpellier by November 29, 2013.

Photos: M ichael Tompkins

you’re exposing and making a decision because you’re not seeing what you’re shooting, really.”

When shooting outside, Cayla does not use too many lights, and he employs them primarily for faces. “For the rest, it’s a matter of filtering, time of day, trying to work out the schedule so the sun is at a specific angle to camera,” he says. “I control the light with frames, for instance, a black frame to cut the light on one side and then a white frame on another side to throw a nice soft white light on a face instead of light sources per se. The beauty of film is that it captures more accurately what you’re seeing; it has a nice sensitivity to what we’re seeing when it comes to exterior days.”

Although Cayla says working on a show that shoots on film is “fantastic” for a cinematographer, he admits that the Haven shoot is gruelling. “After the first episode of the season I have no prep time. I’m shooting while they’re preparing the next episode with another director. I don’t get to see the locations or anything.” Cayla therefore quickly devised an approach that involves working with whatever the environment throws at him rather than

trying to fight it. “If there’s a huge highlight in the water I won’t go against it. I’ll go with it. I’ll try to capture it, try to see how far the film can go,” he explains. “Or I use what’s there to compose. So if the sun is kicking on a car, I’ll try to keep it as much as I can, and if it really affects the lenses or the flare I’ll reduce it. But I try to work with all kinds of different highlights and everything that’s presented in the environment of Chester and the ocean.”

But Cayla is quick to point out that he would not be able to pull it off without the efficiency of his camera crew, which includes A camera operator and second unit DP Christopher Ball csc; first AC Eddy McInnis (see sidebar); B camera operator Patrick Doyle; B camera first AC Gareth Roberts; B camera second AC Mike Snider; and A camera second AC Andrew Stretch. “We have an almost automatic way of working,” Cayla says of his team. “Usually when I light a scene I tell them very quickly what I’m looking for, and I’m involved in the composition, as it influences the lighting setup. Then very quickly we choose a lens together, talk about low and high – and as soon as we say low and high we know what we’re talking about: we want to see more ceiling, more floor. If we’re outside I want to be low because I may want to catch something in the background. Then after that they deal with the setup, I can deal with lighting, the light measurement and the filters I’m gonna use. So everything goes out pretty fast and pretty smoothly.”

Ball’s unique combination of doing A camera and second unit came about after the first season because Cayla needed a second unit shooter who had experience shooting film and with a close connection to the main unit. “The second unit, referred by all of us as “action unit,” has become a consistent weekly shoot, and we often take on quite large scenes, effects and stunts, as well as the usual inserts,” Ball says. “There have been occasions when

a way of going back to those roots. We have mags and all this extra equipment. I do enjoy the loading of cameras, even though it’s tougher for seconds, for trainees. But I believe it’s more pure. Some of the newer assistants use the monitors to pull focus. With film you have to pull with measuring tapes and with your eyes. You have to rely on the operator, who has an optical viewfinder. Some of the digital images are so clear and so crisp a lot of people are tempted to look at monitors now. And there’s nothing wrong with looking at them to help, but as a first assistant I do like the old way with measuring tape and your eyes.

What has helped you develop your craft? Who have been your mentors?

It’s all been on the set. Everything I’ve learned has been observation of people who’ve done it in the past. There’s no formal school for focus pullers, so you develop it through time and experience. I’ve been in film since ’96 and became a focus puller around 2004. Eric [Cayla csc] is someone I look up to for sure. He’s definitely one of the most respected people I’ve ever worked with. He has an ability to be so focused at the job but can also slide a little joke in at the appropriate time. And there are other focus pullers that have been doing it way longer than me that I respect. Like Paul Mitcheltree and Forbes MacDonald, not just as focus pullers per se but as Atlantic Canadian guys that were in the industry 20, 25 years ago when there wasn’t really an industry here, they were kind of the trailblazers for the rest of the assistants. Because the rest of the guys would probably have been from Toronto, but those two were local guys. They started it for the rest of us here in Halifax.

How would you characterize the industry in Atlantic Canada?

I enjoy working here and living here. I can’t speak for everyone, but I’ve personally worked a lot. The industry is a close-knit group. It’s a smaller place. There are probably four main local producers, probably three or four real quality crews. But the skill level and the quality of the technicians is comparable to anywhere, in my opinion. I believe Halifax has been fourth in production –after the three major centres of production, Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver – many times. Now we compete with Calgary and Winnipeg. When I won the CSC Award it was more about putting Halifax on the map and the technicians here and the quality of the people. But we’re in dire need of a studio for sure. It would help the industry so bigger pictures could come here. That’s easy to say but

M ichael Tompkins

From left, DP Eric Cayla csc with first AC Eddy McInnis and A camera

operator/second unit DP Christopher Ball csc.

a little harder to find the $40 million, or whatever it costs, to build one. A lot of the shows that come to Halifax come for the water, like The Shipping News or K-19. So a wave tank or studio space could only help us.

How does being far from the main rental houses affect your work?

We do have PS and Whites and Panavision and Sim. But in my prep I can’t go, “I don’t like that matte box,” and then have 80 of them in front of me to pick from. When I prep, everything’s a day away. If I need a filter, let’s say, we can’t just send transport. That’s part of being a camera assistant here. If you’re shooting film you’ve got to plan for film stock. You’ve got be a little more organized.

What advice would you give to camera assistants coming up in the Atlantic?

If I could tell them one thing it would be about respect and etiquette. I find the young camera assistants sometimes have an entitlement like they’ve been doing it forever and don’t have that respect level that we all had coming up with the person in the position above you. That would be my advice, to maybe learn more about the actual position and the etiquette, and to be a professional on the set. Because when people leave here, DPs, producers, anybody, the way we are as people, people take that back wherever they’re going. So it affects the whole industry.

the action unit is bigger than the main unit. Recently, we started to give a day, or a half day, of prep to Eric while I take over the main unit set as DP, which has worked well with Eric as he has little time to prep normally.”

Although the show is demanding for the team, Ball appreciates being able to learn from Cayla. “He has a way of keeping things simple, efficient and structured while still allowing for creativity and freedom,” Ball notes. “He is a strong yet quiet presence on the set and keeps the day moving efficiently. He really strives for high quality work, and expects that from all of us, so this is not a set that you can get lazy or perfunctory on. His lighting and composition is very considered and thoughtful, but he is not afraid to push boundaries and take some risks.”

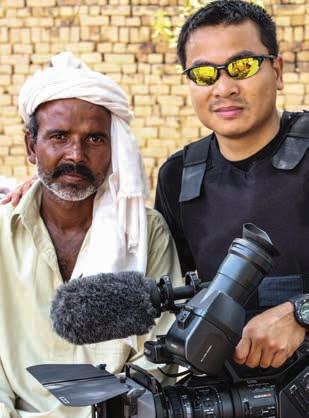

Sarorn Sim csc and the future of

C o rp Cin emat

o rat ograp

e hy

By Fanen Chiahemen Photos by Dan Denardo *

With its saturated colours, shallow depth of field, soft lens and soothing piano soundtrack, the three-minute video “Sonata” is hardly recognizable as a corporate tool. The slick and evocative piece looks more like a classical music video or short film. And shooting the CSC Award-winning video for Dow Chemical Company was “pretty elaborate,” says cinematographer Sarorn Sim csc. “It was shot with an ARRI ALEXA. There were so many lights and big setups.” The idea behind it was “drawing a parallel between music and chemistry to explain that, like the combination of notes in music, the combination of elements in chemistry is infinite, and both result in the creation of beautiful things,” Sim explains.

Because corporate videos have long been internal communications tools for businesses, their production value has typically been low. “They are usually produced using a three-point lighting setup; you cut it, add a lower third with names and titles, and it’s done. Well, it’s gone beyond that,” Sim says.

Sim, who is represented by AVI-SPL, is the producer and director of photography at Dow. In his role, he has travelled to more than 40 countries shooting corporate videos for the Fortune 500 Company, handling anything intended for external circulation, including marketing videos and commercials.

“A lot of companies don’t have the in-house capability to produce the kinds of pieces that I do,” Sim says. “Most companies have departments that produce the head-and-shoulder shots, the training videos, the safety videos, just basic videos.” But he believes there is an ever more substantial role for cinematographers in corporate settings.

“It’s a very rare skill set to have in a big corporation like this,” Sim offers. “But in terms of numbers, it’s a cost savings to the company. Hiring a DP or an agency costs a lot more. So having me here in-house is a huge benefit for them.”

It was a role he initially expected to be merely transitional.

This page: Sim shooting a mini documentary for Dow in Ghana. Next page 1: Standing in the midst of one of the world’s most dangerous slums in Cité Soleil, Port au Prince, Haiti. 2: In the desert of Dubai, United Arab Emirates. 3: Sim on an urban shoot. 4: Sim on a shoot in South Africa.

1

“I was doing a lot of news-type shoots back then; a lot of projects in foreign places like Afghanistan and Pakistan,” Sim says. “I wanted to do something more corporate and agencystyle, so I applied for the job, and I got it. I didn’t think I would be here very long because I didn’t think they would need my skill level here. I was thinking of being here for six months.”

3

However, the role ended up fulfilling a need for both Sim and Dow. “They embraced it, and I’m still here. They were very open to embracing that concept. Their instruction to me was, ‘Ron, we want to raise the bar in terms of what we do in corporate video.’ I said, ‘If you want to raise the bar you should look at corporate videos in a different light than just training videos and instructional videos,’” Sim recalls. “The corporate video has to step up a notch; it can look like a commercial or a movie. It all depends on how you craft the message.” Sim’s latest assignment for Dow took him to Ghana to document Dow employees’ engagement with non-profits in developing countries addressing some of the world’s most pressing problems, including clean water, housing and sanitation.

“The focus isn’t on shooting with the cheapest camera anymore,” he explains. “I have to decide whether to shoot with the ALEXA or

A Day in the Life of a Corporate Cinematographer

By Sarorn Sim csc

There are some people who wake up at 3 a.m. and wonder, “Why am I up?” And then there are people like me, who wake up at 3 a.m. and can’t wait to jump out of bed. I’m sure five-year-olds feel the same way when they’re waking up to go to Disneyland.

Today is shoot day. And after months of prep, we’re finally ready to transfer vision into video. Working on a corporate film is like being in court. You spend days and months cross examining every aspect of your argument as you try to win the hearts

“The focus isn’t on shooting with the cheapest camera anymore. I have to decide whether to shoot with the ALEXA or whether to use the F55 or the Canon. I decide which lenses to use, which lighting package to use. So it’s much more like a commercial production,” Sim says.

whether to use the F55 or the Canon. I decide

4

which lenses to use, which lighting package to use. So it’s much more like a commercial production.”

There seems to be a correlation between the progression of corporate video production and the streamlining of technology, Sim observes. “It’s becoming more affordable for the average cinematographer to achieve that commercial look and feel. You don’t need to spend half a million dollars anymore. You can spend $10,000 or $50,000, and achieve similar results. If you look at an HMI par, it used to cost $10,000. But now you can get something equivalent for $3,000. The technology and resources required for these shoots are more attainable than ever.”

and minds of those who hold the key to your inevitable fate. You not only have to think technically, but just as important, think strategically, legally, and sometimes, even covertly. Meetings in fancy boardrooms equipped with advanced teleconferencing gadgets fill up most of my pretrial/production days. And instead of wearing jeans and a t-shirt like normal cinematographers do, sometimes I’m in a suit!

Finally, when all parties are smiling and charts and graphs and PowerPoint’s are aligned, it’s show time! Sporting my favourite pair of Levi’s and an “I am Canadian” t-shirt that I got for free in a

box of Molson, I’m ready to lock ’n load my cine-camera of choice. There’s nothing more exhilarating than jumping out of bed at 3 a.m. to be on the set of a corporate film. This morning, we’re capturing the sun rising over the Philadelphia skyline. A Sony F55 with a Canon 30-300 cine lens and a 30-foot jib awaits me.

Oh, and the fun part will be launching 300 helium balloons into the city.

0330: After a frantic shower and a brief check of my pulse, I leave my hotel room.

0400: It’s amazing how empty the streets of Philadelphia can be at 4 a.m. Passing by early morning newspaper couriers and half asleep security guards, I arrive at the entrance of our location, Belmont Plateau, a historical park overlooking the City of Brotherly Love. Like a put-put generator, my producer Alan Friedlander has the set already humming with activity. Crews are busy setting up a 30-foot jib, HMI pars, screens and silks. My assistant camera Anthony Sergi is prepping my F55, hooked up to a Flanders Scientific monitor for preview. Scanning my set, I see no one in suits walking around. Perfect!

0500: For this concept, we’re using helium balloons with a message tied to their strings to symbolize the reach and impact that Dow has on the everyday citizen. It’s almost like the “message in a bottle” concept but with balloons. We’re releasing 300 helium balloons in four takes. For this task, we’ve hired a balloon artist and sculptor to help with the setup. After talking to the balloon staff, I take a big sip of helium and run off to check on grip.

0545: The sun is up! The sun is up!

1

2

5

4

Still he feels there is work to be done in changing the mindset of corporations. Doing so would mean better videos for them, as well as more cinematographers in secure jobs (the statistics are foggy on how many corporations hire in-house cinematographers). “My question for corporations is, with the new technology that’s available at reasonable prices, why are they still producing corporate videos using outdated methods and equipment? If cinematographers can step up and prove that the images in these productions can look amazing and that companies don’t need to settle for the status quo when shooting corporate stories, there is nothing that should stop us.”

Sim points out that cinematographers working in corporate settings may need to adjust their communication because creative people talk differently than business people. “You need to understand how to communicate with people in a corporation because it’s not a movie set;

*Alan Friedlander

Clockwise from top left: 1. Working

with AC Scott Morhman on “ A New Day,” a commercial for Dow’s Solar Shingles in Saginaw.

2. On top of a mountain

in Honduras.

3. Making friends in hostile

territory.

4. Camping out on the lava

fields of Samoa.

5. Sim shoots the CSC Award

winning corporate video “Sonata.”

you are working with executives and VPs. They are analytical and are more comfortable when they are working with numbers, spreadsheets and PowerPoint presentations. But I am comfortable with colour palettes, lights and angles,” he says. “So it’s important to grasp communicating on a corporate level. You can’t walk into a corporation and communicate the way you would on set. Initially, the most difficult part was helping executives understand my creative vision. I’ve learned to use a lot of examples for every shoot. I once used a scene from the movie Up to help them relate.”

Sim is hopeful about the direction corporate cinematography is going. “I really do hope that it keeps getting better. I challenge everybody in corporate cinematography to help raise the bar,” he says. “Tell a story instead of purely communicating a message. As a storyteller, take that message and turn it into something more intriguing.”

0549: You know that Sheryl Crow song “The First Cut is The Deepest”? Well, for me, the First Take is The Deepest! You know you’ll roll again, but man, that first take of the day puts butterflies in my stomach and makes my hands tremble like Hiroshima. Thank God for tripods!

0630: After two successful takes, my mind is slowly coming to terms and I start thinking, “Wow, this idea is actually going to work.”

0645: Shit! The balloons we launched in the first two takes didn’t have any red balloons in the mix. How can we not have any red balloons? Red is Dow’s trademark colour. I walk over to the balloon department, take a huge sip of helium and give them my two cents and a lesson on corporate identity branding 101.

0700: Third and fourth balloon launches are a success! Wide establishing shots of the launch are done. Now it’s time to set up for close-ups and cutaways. With the sun climbing fast and daylight changing colour, my key grip Eric Murphy and his team click into full gear.

0900: The scene is wrapped. But working for a multi-national corporation the size of Dow means your day isn’t done – it’s only beginning. With offices in 137 countries spanning every time zone imaginable, I quickly jump on my iPhone to check email, reply to requests from half a world away and prep for upcoming assignments. Today, as we’re filming in Philadelphia, I’ll be working out of our Philly head office. Going directly from set, I walk in wearing jeans a t-shirt.

People in suits and ties look at me strangely. I smile and flash my “I am Canadian” t-shirt like it’s a shield of honour!

Sarorn Sim csc is a four-time winner of the Canadian Society of Cinematographers Award. His clients have included Discovery Channel, National Geographic, BBC and Fox News. He is a graduate of Sheridan’s Media Arts program in Toronto. His mentors include cinematographers Richard Leiterman csc (Stephen King’s IT) and Rodney Charters csc, asc (Charlies Angels, 24). He currently resides in the United States.

�s sss nssns ss ssssssnss sss ss� �� ��� ssss �ss

�sssss� sssssss sss ssss sssssssss� sns����� ssss �sss�sss �snssss�sss �sssssssssssssssnsnssssnnsssssssss� sssssss��ss�nn�ssssssssssssssssss

Grace Carnale-Davis ssssssss sssssss sss ssssss ssssssss ssssssssssss sssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss

Technicolor On-Location nnnnnnnnnn nnnnnnnnnnnnnn nnnnnnnnnnn

technicolor.com/toronto

Thom Best csc Shoots

M use E ntertainment/Back Alley Film Productions Photos: Jan Thijs / ©2013

CTV’s original cop drama Played, which premiered in October, follows a group of agents who are part of an elite, Toronto-based undercover police unit created to infiltrate organized gangs. The agents use surveillance, false identities, character play and skill to gain access to wanted criminals. Director of photography Thom Best csc talks to Canadian Cinematographer about how to shoot an unconventional police procedural that keeps character front and centre.

Canadian Cinematographer:

from other cop shows? What sets Played apart

Thom Best: What makes this series unique is that it shows how the agents must use their own lives as part of their cover and how it takes a toll on their personal lives. The connection to the characters themselves makes it different. It’s more focused on the lives of the cops. This was an opportunity to push the visual language of the ubiquitous cop show and not do the status quo, to try and bring new things to it, new visuals. Every episode, Adrienne Mitchell [series co-producer and co-director] and I wanted to approach as a feature. I know that’s kind of a lofty ambition, but that was the challenge. And it was incumbent upon every director to come at it with that mindset.

CC: How would you describe the visual language of the show? TB: We went after a kind of tobacco-stained look. We went for

Front row, left to right: First assistant director Michael Johnson,

director of photography Thom Best csc, director Jerry Ciccoritti and script supervisor Winnifred Jong behind the monitors on the set of

Played. Opposite page: Lisa Marcos as Maria undercover in Played.

warmth and an amber colour. The show’s creative team – including [executive producer] Greg Nelson and Adrienne – were very clear about what they wanted, something that invited the viewer in, that wasn’t off-putting or cold, something that was welcoming. Adrienne put together a look book that she showed to the department heads, and the images were bold and graphic and they had a warmth and intimacy at the same time. Some of our influences were British TV series, a couple of them in particular, Luther and Wallander, because their style really worked for cops undercover. Wallander especially used a lot of swing and tilt lenses, almost every image in that show was swing and tilt. It was something that hasn’t been done a lot on American or Canadian television. And we really wanted to push the visuals in that way. It was kind of an experiment to see how far you can push a cop show and still get network approval.

CC: Can you talk about the decisions behind some of the equipment you were using?

TB: We used the ARRI ALEXA, and we usually had three cameras [provided by PS]. I also ended up using a lot of DSLR shots too because of the surveillance element of the show. We were able to put a Nikon D800 in areas of cars that you’re not normally able to access, like down in the wheel well, or we were able to get in very small cars and do over-the-shoulder shots. So that was a nice little thing to be able to do. Something that became a real go-to item was the new Kino Flo

Celebs. They revolutionised the way I light, I would say. They’re just an incredible handy tool because they’re both tungsten and daylight. You can dim them without losing colour temperature. They’re small profile; you can put grids on them and double up the grids to really become a focused source, and you can hide them and do away with a lot of the grip tools. It’s an awesome tool. I use them outside for a little bit of fill, and they’re a great way to get a little bit of highlighting. They’re great for small locations, great for night. I’m looking forward to the larger units, the 400 that’s coming out soon.

CC: Being a show about the criminal underworld there are inevitably some interesting night scenes. Can you talk about lighting the scene in the pilot in a nightclub which had these huge ball-shaped installations for lighting?

TB: That’s the wonderful thing about the ALEXA. I rated the camera at ISO 800 and just left it – I never changed it day or night, interior or exterior, and the camera just allows you to shoot with a lot of available light. That was an example of a well-chosen location. That location actually had a place where I could bounce some light, but in a wide shot I could just use those balls of light, and the deep blue LED lights on the right-hand side, it just made everything come together. I didn’t have to augment too much. I did have a few of the Celebs outside because there was so much glass you really had to be selective in the angles.

CC: How did you create the colours and tones you wanted?

TB: For the first episode we had a DMT– Jasper Vrakking – come in, and we set up looks for each of the sets. He emulated, or built, a set of antique filters and we ended up applying that to everything in the show in varying degrees. It really enhances the warmth, and it’s great for skin tones. It also really warms the shadows and the highlights. I also used a set of glimmer glass filters, relatively new filters that just soften highlights.

CC: How did you create distortion?

TB: Swing and tilts were used on close-ups, and they’re great in medium or wide shots. In close-ups it’s tricky because eyes are the important part of the face. There’s a wonderful scene in the Danforth Music Hall – some wonderful close-ups that are very deep but the focus is really specific. And it was great to do that. You don’t always get that opportunity on TV shows.

In the unit headquarters we also built some large louvered glass panels that you could articulate and we shot some stuff through that. Within a 2x5 foot frame there are 10 louvered glass panels that you can rotate. As you rotate them, the images refract through them. If you move laterally through them you get some wonderful images. On longer lenses it’s a great way to refract the images.

CC: Surveillance is a huge element on the show, as you mentioed. How did that affect the way you shot?

TB: We used a lot of reflections. Reflections help hide what’s going on. We’re always shooting into mirrors. They really make a viewer work, as it were. So that was definitely something that ran through the series. Also, not only do you have to cover the scene, but you have to cover it from multiple angles because there are multiple team members on a play and they always have a different viewpoint. So you have to cover their point of view. You’re almost doing reverse masters on a lot of setups, so it keeps us on our toes.

CC: What kind of locations were you shooting in?

TB: Half the time we were in the headquarters, which was a massive two-storey set. Because I was seeing the ceiling, we went for really wide low angles, a little more cinematic for a TV show. So I couldn’t really hang any movie lights, so there are a lot of practical lights in there. I typically work from the floor. Your best

lights are always on the edge of frame, as Vilmos Zsigmond once said, so I was working to the very edge. That was definitely a challenge of that location. Our exteriors were everywhere in the city of Toronto. Basically the downtown core. There’s a life there you can’t fake. And I think we captured that urban life both night and day. In terms of the night light, I really like to embrace the sodium vapour light that’s in the city. I’m able to use a lot of that. I don’t do any big backlights. We worked fairly tight and contained, and that’s the magic of the ALEXA – it allows you to see deep into the background. It’s wonderful to be able to play with the existing light.

CC: You shot 13 episodes, seven days per episode. What was your process in prep?

TB: I don’t get a lot of prep, other than the pilot and second episode. But prep was at a premium because I’m not alternating with anybody. I had to trust my gaffer and key grips to really prep well. And they always did a great job so I could trust them. For the pilot, I was in prep for three weeks. Adrienne has an interesting way of prepping, she’ll take her own little video camera and she’ll go through the entire scene with some stand-ins and block the scene. So that was a real advantage that you don’t get with most television directors. That’s what’s great about working with Adrienne. She’s an amazing creative, infectious energy and she imbued the entire show with that.