17 minute read

Health-Care Equity

EQUITY IN HEALTH CARE

EQUITY IN HEALTH CARE

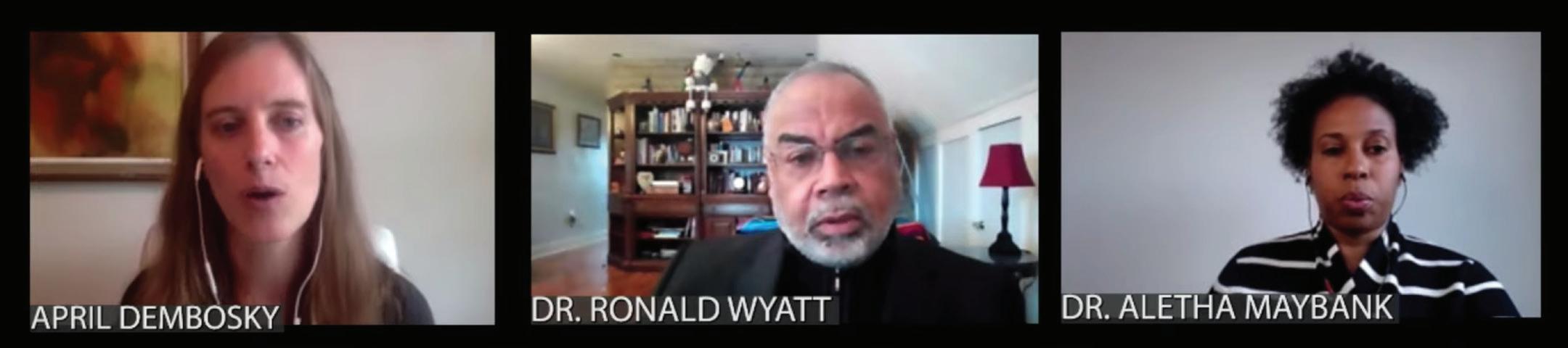

system address the physical, psychological, economic and social impacts of inequity and systematic racism to foster more equitable and healthier communities? From the December 15, 2020, online program “Destination Health: Driving Equity in Health Care.” Part of The Commonwealth Club’s Thought Leadership series, Destination Health, underwritten by Kaiser Permanente. JOSEPH BETANCOURT, M.D., MPH, Vice President, Chief Equity and Inclusion Officer, Massachusetts General Hospital; Founder, Senior Advisor and Faculty, The Disparities Solutions Center; Associate Professor, Harvard Medical School ALETHA MAYBANK, M.D., MPH, Chief Health Equity Officer and Group Vice President, American Medical Association LEANA WEN, M.D., Emergency Physician and Visiting Professor of Health Policy and Management, George Washington University School of Public Health; Former Health Commissioner, City of Baltimore; CNN Medical Analyst RONALD WYATT, M.D., Vice-President and Patient Safety Officer, MCIC Vermont; Former Chief Quality and Patient Safety Officer, Cook County Health; Patient Safety Expert; Health Equity Champion APRIL DEMBOSKY, Health Correspondent, KQED Radio—Moderator

APRIL DEMBOSKY: Dr. Betancourt, I’d like to start this conversation with you. Looking at the situation we are in right now with the pandemic, and you have been charged with the COVID-19 response at Mass. General, and from the very beginning before we really even understood how the coronavirus was transmitted, you anticipated that communities of color would be impacted disproportionately. How did you know this and how did you prepare your hospital? JOSEPH BETANCOURT: I think history has been our best guide on how disasters, both manmade and natural, disproportionately impact vulnerable populations. Clearly I think we could just look no further [than] Hurricane Katrina and how that natural disaster disproportionately impacted communities of color, in low-lying areas, levies that weren’t kept up well. The impact of race, structural racism, what we call the social determinants of health, which really are vestiges not of choice of where people want to live, in the circumstances that put their health and wellness at risk, but really I think an evolution of a whole series of oftentimes very deliberate policies and practices that

lead to “the other side of the tracks.” And as history has told us time and time again, these populations suffer at much greater rates from these types of disasters.

We had our [COVID-19] surge quite early in March of this year, and we anticipated that this would impact communities of color disproportionately. We quickly tried to do things that I would argue brought together a doorstep-to-bedside approach to addressing the pandemic for communities of color, not just focusing on ventilators and bed capacity but really mitigating spread in the same communities that I think have these factors that create a perfect storm that had been talked about for months now, which include multi-generational housing, densely populated areas, essential workers, the need for public transportation before we were telling people to [wear] mask barriers, concerns around immigration, mistrust. These factors in many ways became instrumental. The proof is in the pudding.

We tried to address those in a variety of ways—through community health efforts, mitigating spread by delivering care kits and creating isolation sites for people to safely isolate, to increasing testing and broadening testing criteria when testing was a scarce resource. In our hospital, when we saw that 40 percent of our patients were Spanish speaking and outstripping our resources of interpreter services, [we set] up a group of 15 native Spanish speakers, including myself, who worked with our search teams to make sure that there was always a Spanish-speaking doctor with every interaction, with every patient; to providing information in multiple languages; to setting up a text messaging platform for patients and employees who have trouble getting information through some of the standard channels that we who are more privileged get them.

So those are just some of the things that we did. We tried to throw a lot of things on the wall and see what would stick, see where we could have impact. We use strong public health principles, and principles around the elimination of disparities to drive our work. And we did the best we could. DEMBOSKY: Dr. Wen, we heard from Dr. Betancourt that his hospital was doing some of this community surveillance, some of the work that we typically think is for public health departments to do. We saw a lot of missteps in the early months of the pandemic around testing and contact tracing that in some ways perpetuated inequities rather than help to reduce them. I was hoping you could talk a little bit about what some of these missteps were, and what were some of the lessons that we learned from them? LEANA WEN: I think in time we are going to look back and do a proper analysis of all the many things that went wrong during our response. And I should say [of] all the things that went right, because there are so many institutions, including the one that Dr. Betancourt helps to lead, that did do so many things that set us on the other, right track.

But there were also many mistakes. I think one of the big mistakes is not having a national coordinated plan around many of these issues, including testing, contact tracing. I know that we can see now the importance of testing, that we had missed the early cases of coronavirus coming into the country. We were so narrowly focused, for example, on people coming in from Wuhan in China, that we missed all the cases that were coming from Europe, from other parts of China, because we didn’t have the testing, and, I should say, many months into the epidemic still don’t have sufficient testing. One case was often the canary in the coal mine, and it often meant that there were many others that we just were not picking up on.

In fact, lack of testing and contact tracing was why we had to resort to the shutdowns in the first place. And because we were not able to ramp up testing and contact tracing enough, that’s also why we got to where we are. Every time you had mitigation measures that were able to suppress the level of community spread to a certain level, you’re supposed to get testing [and] contact tracing caught up to that point. But since we didn’t, every time we ended up having a surge upon a surge, and that’s why we’re seeing the catastrophic numbers that we are now in terms of specifically the impact on communities of color.

As all my colleagues here know very well, this pandemic has hit certain communities harder than others. And we also know that whenever there are policies that are unfair, that hurts some in the community, those who are affected the most are always those who have the fewest resources, for whom social distancing is a privilege, who don’t always have the ability to quarantine and isolate because of fear of lost wages, because they live in crowded multi-generational housing, etc.

So I think the lessons that we take out of this, I’d say one key lesson—other than the obvious, which is having this national coordinated response and clear messaging, etc—is the importance of tracking and data, specifically making sure that we are reporting demographic data as well. If we had demographic data around testing early on, we might’ve seen them.

Let’s say a community overall appears to have an acceptable test positivity rate. Let’s say it’s 5 percent in the community, but if Latino Americans are testing at 30 percent positive and African-Americans are testing a 20 percent, that means that there needs to be much more concerted effort toward those communities. Having that kind of drill-down demographic information will be really important as we think through vaccine distribution as well, because we would not want for vaccines to be distributed only to the most privileged communities, and having that kind of data transparency is one way of holding people accountable. DEMBOSKY: I had a follow-up question for you about testing. In California, in the San Francisco Bay area, we had an effort that was intended to increase the access to testing for low-income communities of color. It was a project backed by a Google program. Even though it was intended for low-income communities of color, they required people to register for an appointment online. And as a

result, all of those resources ended up going to white affluent people who came to make use of the testing. So even when we want to do a good job, they’re still these pitfalls, there are still mistakes that can get made.

How should we be on the lookout for those kinds of things? WEN: I think it’s such a good point, and it actually brings up the point about telemedicine more broadly as well. I’m a big proponent of telemedicine and telehealth, having been a practitioner of it for years, but we also know that when things that are new and innovative come up, that despite the best intentions to make it about increasing access, sometimes it could further perpetuate disparities. So I think part of it is being attentive to each of these issues along the way, by speaking to the members of the community who need to be involved in crafting each of these plans that may sound good on paper and maybe with the best intentions in mind, but I think had community leaders been involved in some of these efforts, they probably would have pinpointed the problems.

For example, there have been other efforts across the country where getting a test may require a doctor’s note. But if you don’t have a physician, then you’re also going to be left behind. Or drive-in centers are great if you have a car, but if you don’t, might there be other settings in communities, like testing at churches that might actually get to that more. DEMBOSKY: Dr. Wyatt, I’d like to talk a little bit about how we got here. You went to a segregated doctor’s office as a child, where Black patients could only get walk-in appointments. I’m hoping you can give us the historical perspective of how racism got baked into our health-care system. RONALD WYATT: I think we have for too long been ahistorical, and we need to go back through—I would just describe it as the pain of history to understand where we are now.

When I talk about this then, I’m talking about going back to 1492, and I’m talking about going back to 1619. So when we think about pandemics, I would say the original pandemic in the U.S. started in 1492 and 1619. That was when Black and Indigenous people and other people of color became the essential workers. The idea of social distancing from my perspective started when Black people were chained in the bottom of a slave ship that sailed the Middle Passage, while millions of Black people died, and they became essential workers on sugar cane plantations in the Dominican Republic, the tobacco plantations in Virginia, the cotton plantations here where I am in Alabama.

So this pandemic that we’re in is not an anomaly for Black and Indigenous and people of color populations. That goes through the times of slavery, when Dr. [Samuel] Cartwright described a condition of Black people that he called drapetomania, which meant that you had to have a mental disorder as a slave to want to run away. That goes through the retribution peonage, Jim Crow, when W.E.B. Du Bois . . . described what he called a “peculiar indifference” to the Black populations in Philadelphia. And that goes up to . . . where we are up to mass incarceration, which is now called the new Jim Crow. So I would say that this pandemic that we talk about now should not come as any surprise.

All of the signals were there. They were not anomalies. From my perspective, it’s almost fatalistic to say, “Well, we have these Black, Indigenous and people of color populations who are at higher risk.” They were at higher risk before COVID came to the U.S., and we can use the data.

I so much appreciate Joe and Dr. Wen for the data work that they do to demonstrate this. That data was there and I think in many ways under-appreciated. Those were the signals that if we get hit with something like this, then there are populations that were already devalued, that were in many ways dehumanized, that there were resources that were allocated in an unjust and unfair way that then leads to these outcomes that we see. And these outcomes that we see now in this pandemic really are systematic and they’re systemic. They reflect institutional and structural racism that existed before COVID, and many organizations, institutions and dare I say leaders knew this pre-COVID. So it should not come as a surprise.

The canary in the coal mine for COVID was already deeply short of breath before COVID hit and was ignored. We have to understand why these signals were ignored. Why were they treated with such indifference? Why were there eight or so ZIP codes in New York City that stood out as very different when COVID hit New York City—I was there during that first surge of it—and then how it spread across the country? So back to Joe’s point, then when we think about what we like to now call the social determinants of health, they are not new. This is the stuff that’s been killing us for hundreds of years. Those things have made Black and Indigenous and people of color populations disposable, people who live in sacrifice zones, who are impacted by environmental racism, segregated housing, under-appreciated jobs, and the list goes on.

I do believe that a core to this from our profession is a lack of respect, inadequate compassion, and the stripping of dignity from people of color, Black and Indigenous populations. So if anything, this has taught us, don’t ignore these signals and assume that they’re somehow anomalies. I was inside a federal [agency] that had a playbook to respond to a pandemic. We went through scenarios. Where would be the supply chains; these are the federal stockpiles; how to handle transportation distribution. That was a complete playbook that for some reason, I would say it’s systematic, was ignored. And now we’re playing catch up.

But if I began to think about what’s driving this [with] Black, Indigenous people of color populations, it is mistrust, it’s distrust, and it’s a lack of trust. That is historic. For us to move forward, we have to remove this ahistorical thinking. We have to remove what’s been called a myth of meritocracy. How will we, particularly now going forward, begin to allocate resources to the places where they’re most needed, not where they most wanted, but where they are most needed.

The data that Joe has, the data that Dr. Wynn has, the data that Aletha is working on at the AMA [American Medical Association], it’s just a road map to show you where to go to do work that can be sustainable, so that this is more than just a moment.

This has to be more than a moment. ALETHA MAYBANK: [Let’s build] upon the history and the context of race and racism in this country, and getting asked about [how] medical students have been taught that race is a biological construct rather than a social one. If I could explain some ways that this idea permeates our health-care system, is actually even built into the test and the algorithms

that doctors and the health-care system use to determine how to deliver care or what types of care people should have. I would start off by saying that it’s not only medical students who have this notion that race is a biological construct. This is really an American belief and is also very much rooted in our history. It’s the belief and actions that races are biologically distinct groups that are determined by genes. This is known as racial essentialism, but it really has no scientific basis. The Human Genome Project of 2003 told the science community that we are genetically more alike than there is variation. The variation is very small. But this belief has really gone across generations and it has really created harm.

Just a little more context, because I’m not sure how well-informed everyone is around the race conversation, I think one of the barriers that we have in this country is the analysis in terms of structures and systems of power. We have a hard time talking about race and racism, but what’s nice to see now—and hopeful we see now—is that more people are building that analysis.

But race really was documented as a concept developed in the 18th century to divide human beings into groups, typically based on their physical appearance, their skin color, but it also could be social cultural backgrounds. For those who have been in data for a long time, when you look at old data sets, you will see Italian was a race, being Jewish was a race. And so race actually has evolved over time. It really has been used to establish English social hierarchy and at one point ultimately to enslave human beings. Race itself doesn’t describe the complexity of genetics or ancestry. Genetics and ancestry are really very distinct terms. Ancestry more reflects our human variations that are due to kind of geographical origins of our ancestors. That’s different than race. Race is merely a social and political construct that, as I said, has changed through time. Even now our U.S. Census changes the definition of race every 10 years or so.

Race has use in the sense of what has been talked about so far and in describing what is happening to people [in terms of] race and ethnicity, and to communities. It’s not that we shouldn’t collect information on race, but we have to be very careful how we use that data to generate solutions as well as treatment. We really have to look at the impacts of racism as a system. This is Camara Jones’ definition of [racism: It is a] system of power that structures opportunity and assigns value

based on skin color, advantaging whites and disadvantaging people color. It’s [with] that system that we have to have a better sense of what is happening—the impact of that system on race, what is happening to people we have to better understand in the health-care system. So the American Medical Association this past November passed a policy on racism as a public-health threat; the second policy was [to] actually rid health care of racial essentialism; and the third was to eliminate race as a proxy for genetics, ancestry and biology in medical education research and clinical practice. Because what medicine and the health community at large has really done, whether it’s intentional or not, it has made treatment decisions based on race, which again has no biological basis for disease.

What race-based medicine would tell me is that I, as a Black person, if I go into a health center and I need to do a test for my lung function—spirometry, as they call it—or my renal function, my kidney function, and they’re going to look at the rate of filtration. If I were to deliver a baby, I would be evaluated based on being Black and whether or not I had the ability to—if I had a C-section before—deliver that baby vaginally. So my treatment would actually be adjusted differently than that of a white person. What this says is that something that’s different about my lungs and my kidneys and my ability to have a baby, and that for some reason it’s a biological trait, but that’s just wrong. These tools are used on a daily basis to decide who gets medication and different treatment plans, and they’re just unintended consequences that we know cause harm.

And we know as an example, going back to the filtration rates for kidneys, if I’m identified as a Black person, it could suggest a better kidney function. Therefore if I have a higher filtration rate, it may delay the kind of specialty care that I get, or delay me getting kidney transplantation.

These are the ways in which right now there’s much greater interrogation, and a lot really led by med students and residents, on how are we using race, how is it causing harm, what are the intended consequences and what do we need to dismantle this aspect of bias that is built into how we deliver care at the health-care system? And then how do we also better understand the impacts around the experience of racism and other forms of oppression in this country?

Image by Elf-Moondance.