23 minute read

SHINE ON

SHINE ON A LESSON IN HUMILITY

When I was 19, I traveled to the poorest country on this side of the world. As a middle-class, Midwestern white-kid traveling to Haiti on a mission trip, I had strong faith and missionary zeal, but nothing could have prepared me for the kind of abject poverty I had only ever seen depicted on TV.

Advertisement

I traveled with five friends to a Catholic boarding school that served 300 of Haiti’s poorest and brightest students. Upon arrival, I noted the blue-helmeted UN soldiers who stood guard around the airport, rifles in hand, as we made our way to the trucks that drove us to the school. The driver swerved around other cars, demonstrating a driving skill that one can only learn in an area where there are no rules of the road, traffic lights, road markings or other tools of order.

We pulled up to the solid-metal front gate of Louverture Cleary School in Port-au-Prince, and waited for security guards to allow us beyond the 12-foot-high cinder block walls with broken glass embedded in the tops to prevent anyone from climbing over them. But as the gate closed behind us, the world blossomed. Exotic trees and vibrant flowers cast comforting shadows in the clean, bright compound. We arrived during opening prayer – 300 students assembled in rows. Boys wore crisp yellow shirts with khaki pants, and girls donned plaid skirts. “Their uniform is their most prized possession,” the school’s president later told me. “It means they get to go to school.”

We were there to install solar panels on the roof of the school, ensuring a renewable source of electricity, since the country’s infrastructure didn’t provide reliable power. We would also work with St. Mother Teresa’s local Missionaries of Charity in their orphanage.

But I didn’t get to spend any time on the solar panels and just one morning at the orphanage. The experience was heartbreaking. We spent half the morning in the infant nursery, holding and feeding the babies. The image of one child with a head deformity from surviving a botched abortion will never leave me. The second half of the morning we spent in the toddler room, where we weren’t allowed to hold or touch the children. The Sisters explained to us that they would likely never be adopted, and it was best for them to unlearn their need for physical affection at a young age. None of the children had names.

I spent the bulk of my time in a large area of sand and dirt and small rocks adjacent to the soccer field. The school president explained to me that Haiti had very little infrastructure. Because there were no sanitary services, the school had to reuse, burn or bury their trash – and the hole for their garbage was full. And so I spent my days in the blazing heat, work gloves on, digging a garbage hole.

At first I was angry, and I funneled my frustration into the manual labor. I had prepared for almost nine months, raised thousands of dollars for the trip, learned about the country and its culture. My friends were installing solar panels and I was digging a garbage hole, usually by myself.

But after some time and prayer, God spoke to me. The mission trip, in my mind, was all about me: The incredible work I would do and the hope I would bring to the Haitian students. I had traveled to the poorest country on our side of the planet, and, somehow made that trip all about me.

But the students at Louverture Cleary didn’t need me. They needed a hole in the ground to place their garbage. God had me literally dig myself into my own hole to understand my own selfishness.

The week after I returned home, I was riding in the passenger seat of my mom’s car. It was garbage day, and I was looking at the overflowing bins at the end of the suburban driveways. And then a thought occurred to me. I said to my mom, “I am so grateful that someone takes away our garbage.”

DOMINICK ALBANO is the director of digital engagement for The Catholic Telegraph, as well as an author and national speaker. He and his wife have been married for 13 years and have four sons.

CATHOLIC AT HOME PREPARE FOR A MORE SOULFUL THANKSGIVING

We go around the table every year: “I’m grateful for my family and friends,” somebody says. “I’m grateful for pie,” one child pipes up. Thinking ahead to my turn, I want to voice something that’s heartfelt and unique, but, most years, I realize that I’ve done little reflection on the details of my life that would yield the solid answer I’m looking for. Similar to waking joyfully on Christmas morning, I want to experience Thanksgiving with a deep, peaceful gratitude grounded in recognizing God’s presence and blessings. To aim for the same, take small steps toward living simply and generosity while taking actual record of what gives you joy.

LIVE SIMPLY St. Therese prayed, “Jesus, help me to simplify my life by learning what you want me to be, and becoming that person.” Living simply is much more focused on the soul than it is material possessions. God has blessed every one of us with gifts, passions and charisms. Recognizing what they are, then maintaining a lifestyle to nurture them is living simply.

For example, you might be a person who thrills in hosting and get-togethers, so having an abundance of plates, table cloths and space in your home would be “simple” for you. God put desires for adventurous homeschooling in my heart, so we have a good vehicle for our travels and we budget toward experiences. Our possessions and schedules should lean into who God created us to be as individuals and as families. What lights a spark in you? In your kids? Ask the Lord to reveal it to you, and live accordingly.

BE GENEROUS I began pursuing a simpler life more than 10 years ago, the fruits of which our family saw immediately. An expecting mama bent on nesting, I wanted to rid our house of excess to make way for our third child. I could have sold our extra stuff, but with a due date looming, I rushed to give it away and stumbled upon generosity completely by accident. Our family had been on the receiving end of others’ generosity countless times, but having the chance to do the same was a gift equal in proportion. My husband and I parted with small stuff at first – clothes the kids outgrew, home decor and books – and we saw how much people appreciated receiving them. To put it simply, we saw more clearly how very important people are and that detaching from things we didn’t need could make us channels of God’s generosity. Eventually, Andrew and I had opportunities to give in bigger ways, and because we had been practicing, we could do so with joy.

NUMBER YOUR BLESSINGS G.K. Chesterton said, “Gratitude is the mother of all virtues,” so cultivating thankfulness within ourselves is a surefire way to holiness. In 2004, I spotted a book called 14,000 Things to be Happy About at a bookstore. Flipping through, I realized that it didn’t apply to me specifically, so I bought a notebook instead and decided to write my own. Try this yourself!

Use a notebook, or make a spreadsheet. Have your kids start their own, as well, to encourage gratitude in their hearts. In noting the things that bring us joy – from the aroma of coffee to learning a baby is on the way – we open our eyes to the ways the Lord upholds us. In times of faith, my “happy list” has only made my smile wider; in darkness, I see how God buoys my heart.

Gratitude is a lifestyle, not a one-time event. It takes slow, small, steady steps to redirect our hearts, lives and families to see how present the Lord is – steps that lead to authentic thanksgiving and deep, soulful peace.

KATIE SCIBA is a national speaker and Catholic Press Awardwinning columnist. Katie and her husband Andrew have been married for 11 years and are blessed with six children.

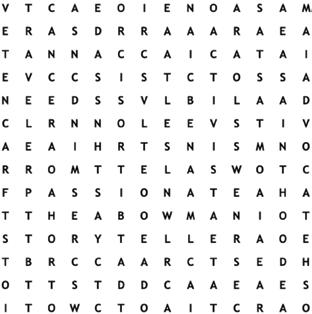

s Thea Bowman

Born and raised in Mississippi, Thea Bowman grew up in a Protestant home. Though her grandfather was born a slave, her parents were strong-willed and resilient. They both followed their dreams! Her father became a doctor and her mother, a teacher.

Thea’s teachers, who were Sisters, inspired her interest in the Catholic faith. She converted to Catholicism at 9-years-old! Not too long after, she joined the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration in Wisconsin at the age of 15. Thea was appalled by the racism she saw in the Church and worked vigorously as an advocate for racial harmony. She traveled all around the country sharing her gifts of storytelling and music to help break down racial barriers. Her vibrant and passionate personality inspired and opened the eyes of many people.

In 1984, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Despite her illness, she continued her inspiring work, even as she grew weaker. She died in 1989 at the age of 52, but is currently on the path to sainthood!

In the spirit of Sister Thea, pray that we might stand against prejudice and racial injustice wherever we see it, and pray that Sister Thea may one day be canonized a saint!

I can change things. I can make things happen.

ACTIVIST ADVOCATE CANCER FRANCISCAN PASSIONATE

RACISM SAINTHOOD STORYTELLER THEA BOWMAN TRAVELER

St. Benedict the Moor Church in Dayton is the most recent church in the United States named for the 16th Century Italian friar whose parents were African slaves.

1703: Congregation of the Holy Spirit (the Spiritans) founded to minister to the poor.

1794: First Spiritans came to the U.S. They originally ministered to European settlers, and later branched out to African Americans, especially with the support of St. Katherine Drexel.

1873: The first Spiritan fathers moved to Russia, OH.

1999: St. John, Resurrection and St. James Churches merged to form St. James-Resurrection Parish.

2003: Groundbreaking held for new St. Benedict the Moor Parish.

2005: St. Benedict the Moor Church was dedicated.

2014-2015: St. Benedict the Moor parish began operating consolidated St. Benedict the Moor School in the building of the former Resurrection School.

"Some of the design staff (myself included) had concerns about how satisfactorily tapestry images would translate into stained glass windows. As it turned out... these windows were brilliant and spectacular." — Ron Bovard in Windows for the Soul

Born to African slaves, Benedict was an Italian peasant who was invited to become a hermit because of his dignity and charity when insulted over his heritage. The term “moor” comes from the Italian word for “black.” He joined a Franciscan friary as its cook, and eventually became its Guardian (leader) because of his wisdom as a confessor and skill as a healer, although he couldn’t read and was never ordained. After his term ended, he insisted on returning to cook again. He is especially popular in Spanish-speaking countries, where he has more than one local feast day, and one is one of the “incorruptibles” – saints whose bodies have never decomposed. Designed by Bovard Studio of Fairfield, IA, the stained glass Stations of the Cross were inspired by an African tapestry given to Father Francis Tandoh, and depict the Passion of Christ in a traditional African setting. The bright colors and bold patterns of the glass throughout the church contribute to its contemporary and African design notes.

“We wanted to make it so people enter the church and see faces like theirs, the way you might enter a church and see it is a German-style church. The Jesus on the cross is a black Jesus, to show that Christ is for all, and the window over the altar is the people in the pews. It says to them: We all rely on the help of God, we all reach up together to the place of God.” — Father Francis Tandoh

Dionne Partee-Johnson

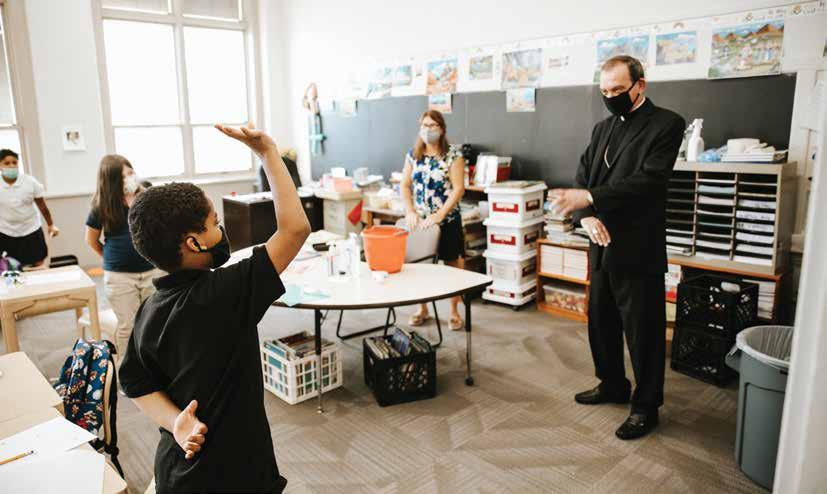

Catholic community is family for Cincinnati educator

BY REGAN MEYER

Catholic education and Cincinnati have always been a central part of Dionne Partee-Johnson’s life. Since attending elementary school at St. Joseph on Cincinnati’s West Side, she’s either been learning from Catholic educators, or teaching the next generation of students in Catholic schools.

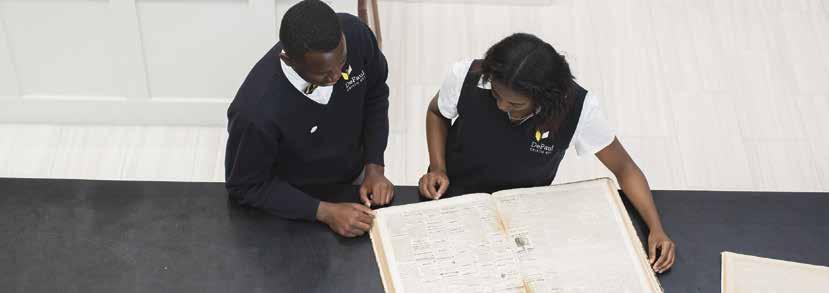

After graduating from Xavier University, Partee-Johnson worked at St. Joseph as the secretary. For 28 years, she worked in Catholic elementary education, eventually rising to the principal’s job at St. Joseph. After a brief break in 2018, she returned to Catholic education as assistant principal at De Paul Cristo Rey High School.

“I have always been in Catholic education, and I will definitely make sure that I continue in Catholic education. I would have it no other way,” said Partee-Johnson.

When Partee-Johnson entered Catholic education in 1992, she wanted to give back to the students of the communities who made her Catholic education possible.

“It’s an awesome feeling to be able to talk about and share my life journey with students, to bring some reality to them and life. But, I’m still able to be Christ-centered. I wanted to give back to the roots of where I came from,” she said.

Partee-Johnson’s favorite part of Catholic education is the ability to be Christ-centered at her place of employment.

“The spirituality. The ability to pray in schools. ... The ability to share my life and to share the spiritual part of my life, to be able to talk about Christ has been rewarding to me,” she said.

She also enjoys exposing her students to the beauty of the Catholic faith. During her time at St. Joseph School, about 40 students became Catholic – some were even baptized at the school Masses!

“We have flexibility and are able to show the Mass. School is where you do a lot of evangelization, and we definitely try to use that to our advantage,” she said.

Partee-Johnson has seen the benefits of Catholic education from different sides. Not only has she been a student and an educator, she’s also been a parent to Catholic students.

“As a parent, I couldn’t keep my eyes on my kids at all times. It was a safe feeling to know that I had other people who were saying the same things. There were other people that were speaking the same language and speaking about love and all of the same things that we valued,” she said.

For Partee-Johnson, the Church community is an extension of her family. Growing up poor in Cincinnati’s West Side, Partee-Johnson said her church family emboldened her through love and prayer.

“We knew we were going to be okay, because we had our family and we had our church family and somehow those weren’t separate. They were one and the same,” she said.

When her teenage son was murdered in March 2018, ParteeJohnson’s church family was there every step of the way.

“My church family, including the archdiocese, was definitely there for me and my family,” she said. “I never felt closer. Not that it took a tragedy to happen in order for me to recognize that, but, there is a huge sense of family in that. ... I have always been centered around Christ. Even with the tragedy of losing my son, I’m still able to turn to that.”

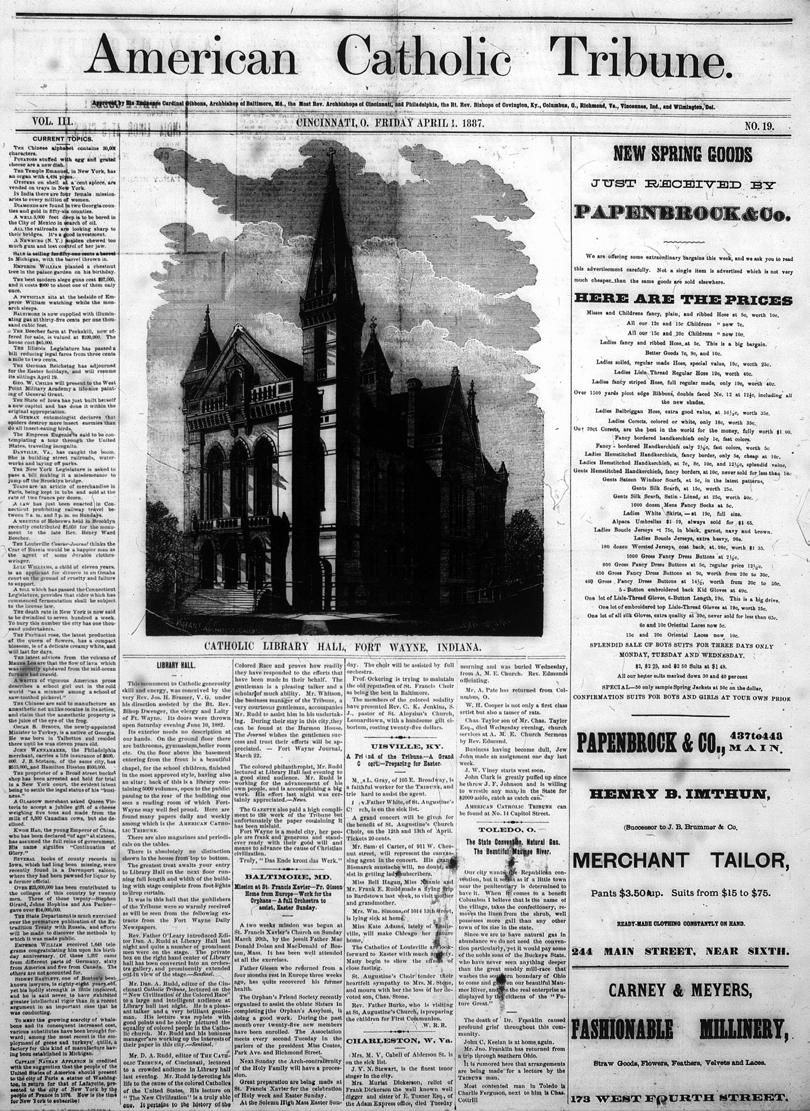

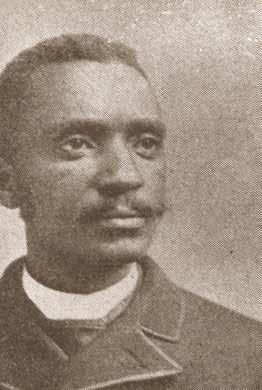

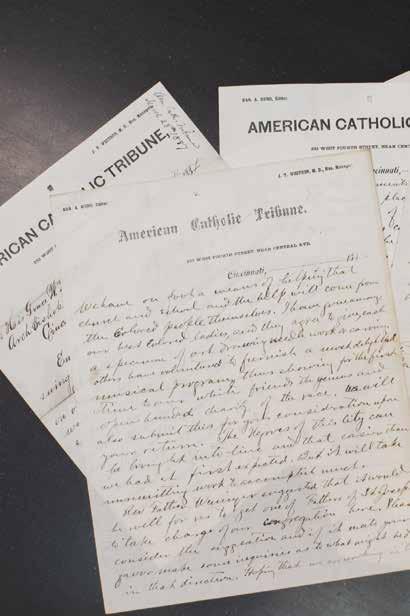

DANIEL RUDD “The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man”

BY SARAH ATER

Daniel Rudd can be counted as one of the most high school and attended St. Raphael Church. influential Catholics during his time in the While there, he began his work in newspapers and Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Indeed, his influence established the forerunner of the ACT, the Ohio State reached throughout the U.S. A man Tribune. During this time, he was of deep faith, zeal for justice and active in promoting racial equality, untiring activity, Rudd founded advocating for racial integration in the American Catholic Tribune the Springfield schools. (ACT), the first Black Catholic He wrote the Catholic newspaper, and the National Black Church was “the only Rudd began publishing ACT in Catholic Congress. His Catholic place on the continent, Cincinnati in 1886. His main faith influenced his world view – he saw the Church as the vessel where rich and poor, audience for the newspaper was Black Americans, but Rudd knew of truth, justice and equality of all white and black, must that a large number of subscribers people before God. drop prejudice at the were white. He used the newspaper threshold and go hand to share the Catholic faith, asking He wrote, the Catholic Church was “the only place on the continent, in hand to the altar. his readers to give the teachings of the Church a fair hearing. By where rich and poor, white and observing history, they could see black, must drop prejudice at the threshold and go the teachings of the Catholic Church supported and hand in hand to the altar” (ACT, Aug. 9, 1890, 2). uplifted the lowly, the poor and those cast down by Born into slavery in Bardstown, KY, in 1854 to society. Robert and Elizabeth Rudd, Daniel and his family In ACT, Rudd also advocated for the recognition were devout Catholics and served as sextons at St. of the equality and the dignity of Black Americans; Joseph Proto-Cathedral. He would later reminisce that no race is better than another, and that all about receiving instruction from the parish priest. are brothers and sisters before Jesus. Rudd was a As a young man, Rudd moved to Springfield, OH, hopeful and optimistic man, but he acknowledged to live with his brother, Charles. There he completed how the stain of racism seeped into the Church,

and he considered those Catholics who would separate people based on skin color as “less than Catholic.” In the pages of ACT, Rudd promoted the rights of African Americans on a practical level. He advocated for desegregation and he wrote passionately for higher education opportunities and vocational schools. ACT published through 1897.

When Rudd founded the Black Catholic Congress, his goal was to mobilize the laity into action. He was convinced there were more Black Catholics than what was known, if only an organization would rise up to give them a voice. The organization met five times between 1889-1894,

the second held at the Cathedral in Cincinnati. However, because of the resistance met from some in the Church when talking about racism explicitly, the Congresses had to proceed gently, as amalgamation was still opposed in the Church. The Congresses focused on labor and trade unions to admit African Americans; the ongoing African slave trade and the support of “colored [religious] sisters.”

We remember Daniel Rudd for his deep faith and commitment to truth. He encountered many obstacles in his work, the persistent racism of people from within the Church, and saw the growing reality of Jim Crow laws. But he also saw the good in his fellow man and the potential for what humanity could be. His hope remained because he did not leave it with man, but placed it all in Jesus Christ.

Further reading: Gary Agee, A Cry for Justice: Daniel Rudd and his Life in Black Catholicism, Journalism and Activism, 1854-1933, 2011.

Letters written by Daniel Rudd are housed in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati archives.

RACISM IS AN ISSUE OF DIGNITY

Why is racism the subject of a podcast devoted to pro-life issues? In their 2018 Pastoral Letter, Open Wide Our Hearts, the U.S. Bishops wrote, “As bishops, we unequivocally state that racism is a life issue.” More recently, Archbishop Schnurr stated, “Opposing racism must… be an integral part of our pro-life witness as Catholics.” Racism is an issue related to the dignity of human life, and that makes it a pro-life issue.

Thus, this month’s interviews feature several people whose stories show that racism still exists. If you don’t believe it, you need to hear their stories. Then, look into your own heart, and ask the Holy Spirit to guide you in what you should do to address this problem.

Here is a list of the month’s podcasts:

• Stories of racism today • Bishops say “Racism is a life issue” • “But all lives matter!” • First steps in ending racism

BOB WURZELBACHER is the director of the Office for Respect Life Ministries. He and his wife, Cindy, live in Sharonville with their two young daughters.

A CLOSER LOOK THE PURCELL BROTHERS, ABOLITION AND THE CATHOLIC TELEGRAPH

“History” is not the accumulation of facts in the past, but rather what we say about, and the use we put to, those facts. This is not to say the facts are unimportant, nor should they be manipulated by the historian. A conscientious historian wants to be as thorough and careful as possible so the story she tells about the past is not distorted. But she will necessarily have to use critical discernment about how to present those facts, including such factors as the political, economic, social and demographic contingencies in which they are discovered. While it is neither her role to excuse nor judge the people whose story she tells, the careful historian does contextualize her subjects in order to try to understand their motivations and intentions. Perhaps most importantly, the historian’s work allows us to learn how we have become who we are in order to try to become who we should be.

THE PURCELL BROTHERS The story of Archbishop John Baptist Purcell and his brother, Father Edward Purcell, as it pertains to the 19th Century abolitionist movement, is an excellent example of this understanding of history. While they were far from perfect and their story leaves us wishing they had done more for the cause of emancipation, the moral integrity of these two fine priests leaves a positive legacy. And it puts the Archdiocese of Cincinnati and The Catholic Telegraph squarely in the story of African American history during and after the Civil War. of Cincinnati from 1833 until Cincinnati was made an archdiocese in 1850, after which he was archbishop until his death in 1883. Father Edward Purcell was a priest of the archdiocese and editor of The Catholic Telegraph from 1840 to 1879. With their respective platforms, the Purcell brothers became the first and leading Catholic voices in the United States for the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of slaves. As Father David Endres wrote in his Ohio Valley History article, “Rectifying the Fatal Contrast: Archbishop John Purcell and the Slavery Controversy among Catholics in Civil War Cincinnati,” after “mild protestations against slavery, [Archbishop] Purcell became an outspoken proponent of . . . emancipation.”

As early as 1838, for example, Archbishop Purcell delivered a speech in which he condemned the “virus” of slavery. But, noted Father Endres, when The Catholic Telegraph reported the speech (presumably under the guidance of Purcell) it hedged on the question of emancipation, noting that, “however desirable,” prudence counseled against it at that time. And Archbishop Purcell “refrained from taking a vocal stand in the decades before the war,” explained Father Endres. Like many of his brother bishops, Purcell feared the political, economic and social upheaval that sudden emancipation would cause. Of course, from our perspective, this reticence is indefensible. Fundamental human liberty should not be subject to such considerations.

THE TELEGRAPH CONDEMNS SLAVERY But while it regrettably did not occur earlier, these attitudes changed dramatically over the years until about 1860, when Archbishop Purcell became the leading Catholic prelate for the cause for emancipation in the U.S. Church. The Sept. 3, 1862 edition of The Catholic Telegraph, for example, published a lecture by the archbishop, condemning the “sin of . . . holding millions of human beings in physical and spiritual bondage.” And in an April 22, 1863 editorial, probably jointly written by the Purcell brothers, The Telegraph became the first diocesan Catholic newspaper expressly to condemn slavery and support immediate emancipation.

In “The Church and the Oppressed,” the paper opined that “the doctrine of the unity of the human race [is] a fundamental doctrine of Christianity,” and that, therefore, no historical contingencies or contexts can justify the continuation of slavery. The following Sept. 9, another editorial declared, “The mark of nobility, the image and likeness of God is stamped on every soul. ... It implies equality in all that is essential to manhood, equality in origin, equality in destiny, and in the right to means of fulfilling the destiny.”

While it may seem like an unexceptional declaration in 2020, in 1863 the archbishop’s uncompromising stand drew widespread criticism within the hierarchy of the Church in the U.S., to the shame of other bishops and the credit of Archbishop Purcell. And even though he met resistance in his own archdiocese, Father Endres explained, Archbishop Purcell “was successful in bringing attention to the moral and social ramifications of the slavery question.” And he demonstrated that “some Catholics were willing to stand in support of emancipation and the honor of the nation,” concluded Father Endres.

We can, and should, regret Archbishop Purcell’s inertia before the Civil War. But we can also learn from it, using it as a cautionary tale about our own resistance to eliminating barriers to racial progress, regardless of how subtle they may be. And, while we do not deny that this lethargy clouds his legacy, we also must affirm his moral growth and recognize the positive contributions of Archbishop John Purcell – along with his brother, Father Edward Purcell – to the story of African Americans in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati and beyond.

DR. KENNETH CRAYCRAFT is an attorney and the James J. Gardner Family Chair of Moral Theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary & School of Theology. He holds a Ph.D. in moral theology from Boston College, and a J.D. from Duke University School of Law.

Retirement Fund for Religious

Please give to those who have given a lifetime.

Senior Catholic sisters, brothers, and religious order priests served for years, usually for little pay. Today, many religious communities lack adequate retirement savings and struggle to provide for aging members. You can help.

retiredreligious.org

Please donate at your local parish December 12–13 or by mail at: Office for Consecrated Life Attn: Maria Reinagel 100 E. Eighth Street Cincinnati OH 45202 Make check payable to the Archdiocese of Cincinnati/RFR.