1 minute read

Brown Cookies

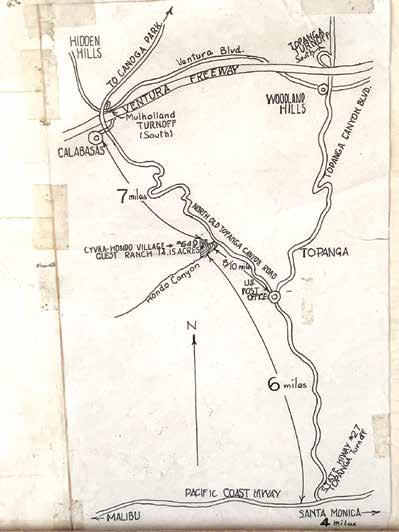

taunted us: “Well, sue us then.” Our choice, and the choice facing the other landowners, was to sell it to the State or lose it to eminent domain.

Finally, in the 1990s, while I was busy earning my doctorate, Father told me he and Mom had decided to sell. They were growing older, and I had established my home just up the road from them.

Advertisement

The forty acres had a market value of $600,000. But how do you sell a landlocked parcel? The State paid $100,000, which my parents split with my aunt and uncle.

We’d been defeated. Yet, for the first time in my parents’ life, they had a savings account. Now they could live out their years in their beloved Hondo Canyon cottage.

For me, it wasn’t so simple. Like the plate of fallen cookies, I took the loss of that forty acres hard. The land was, in many ways, a sacred part of my heart and soul. It represented not only my happy childhood in Topanga Canyon, but my whole family’s history in this beautiful and unique place. Land was, and always had been, our wealth, our safety, and our security from a busy and fast-growing City of Angels. My dream of living at the top of the mountain, like my father’s, had died.

I now also understand the great ironies at play. In the effort to preserve land for public use, the State had disrespected private stewardship. Most people don’t realize that Musch Trail in Topanga State Park just off Entrada, is named for the Musch family, who did not want to sell their ranch but had it taken from them by the State. The same land America had swiftly taken from Mexican families and their Spanish land grants. The same land from which “Californios” had displaced Chumash and Tongva families, who’d been living on it and caring for it for thousands of years.

For further information about this series of events, see The Topanga Story, published by the Topanga Historical Society. (Topangahistoricalsociety.org)