10 minute read

NOTES FROM THE FIRE ESCAPE

from JUNE 2021

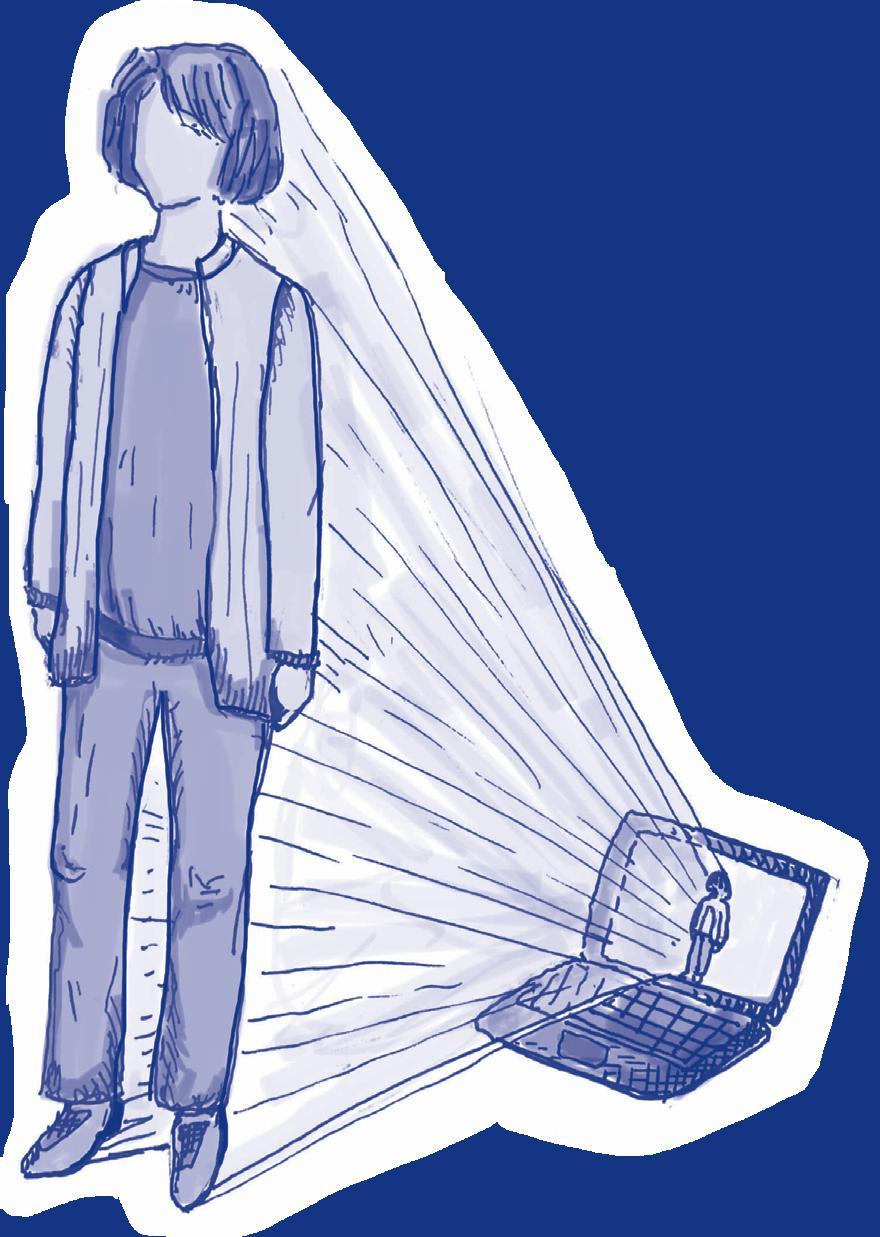

the virtual classroom diminishes whatever social advantage height might normally offer. A level playing field that nullifies one’s stature is one of the things Vijaykumar loves most about Zoom. “You have to sort of announce yourself before you talk,” she said. “Being a small person, in general, you usually don’t take up a lot of physical space and sometimes you might not end up taking a lot of space in the conversation.” Though he also emphasized the many downsides of the virtual meeting space, Reddy still echoed Vijaykumar’s comments, arguing that online, one is “physically equal to everyone on screen.” I asked everyone I spoke with if the idea of acquaintances being unimpressed with their height in a first in-person meeting results in any anxiety. Lopez said that she had not given it much thought and that she is more concerned about her own reaction to other people’s heights. “Out of nervousness or awkwardness, I would probably say something like, ‘Whoa, you’re short,’ and then immediately regret it.” When I made this same inquiry to Ren, she quipped that she’s “grown into it.” I feel that through my conversations, two critical pieces of information were revealed. The first is that people are really bad at guessing height over the internet. The other is that the virtual meeting space has helped to expose the physical world’s many shortcomings (no pun intended) when it comes to creating an environment in which everyone feels comfortable being a part of the conversation. It may be a tall order (pun intended), but as we leave the keyboard for the chalkboard, it will be in everyone's interest for us to render size irrelevant.

Illustration by Rea Rustagi

Advertisement

Front row seats to a New York neighborhood’s quiet cabaret.

BY BECKY MILLER

At 2:30 p.m. on a Tuesday in late April, I leaned against my metal fire escape, hoping to see something interesting unfold below me on Amsterdam Avenue. Maybe it was because I had just watched West Side Story, but I was aching for some action. Ideally, I would, from my perch, witness a pirouetting street gang or a knife fight, or spot a soda-stacking ex-delinquent whose gaze I could hold long and tenderly. I made myself some microwave popcorn and settled in, ready for New York City to explode before my eyes. I first noticed a kid steal his mom’s phone out of her hand and run up and down the block with it. He was like Chris Rock’s excitable, foamsword-wielding son in What to Expect When You’re Expecting, clumsily sprinting around with so much ebullience that people began to stare. He grinned and his mom laughed as he waved his prize like a pirate with newly-found treasure. Then, quickly remembering how to be charming, he caught up with his mom and held her hand. Antsy, I started counting things, searching for excitement or weirdness in the quantity of stuff on the street. There were seven overflowing trash bags on the corner. Nine parked bikes on the block, more zooming by in the bike lane. One person biked past standing up and

I felt a thrill of vicarious excitement. I understand biking standing up to be a near-religious experience, up there with parting the Red Sea and smoking a drunk cigarette.

I saw three bare, hairy chests in one minute. Immediately after, a man in a yarmulke pushed a double stroller with only one child in it, which reminded me of Hemingway’s famous six-word short story—“For sale. Baby shoes. Never worn.”— but more Jewish. I sighed with relief when I noticed challah sitting in the other stroller seat. The restaurant below me only had two outdoor dining bubbles, an undeniably sad number of outdoor dining bubbles to have. An elderly couple stood up and left one of them. The woman had a watch that looked like one my mom had—black leather band, thin, rectangular face. Maybe that’s just what most watches look like. She walked a healthy two steps ahead of her man and he followed like a puppy. They eventually moved next to each other and crossed the street. I soon lost them.

The sight of this sweet couple quelled whatever expectation of drama and commotion I had been holding on to. The streets were not in a frenzy; it was a Tuesday afternoon. I was reminded of Paul Raci’s speech in Sound of Metal where he tells Riz Ahmed’s character, the newly-deaf Rueben, to look for and cherish life’s “moments of stillness,” and Rueben’s contentment when he finally listens. It was right then that I squashed my shpilkes, chilled out, and enjoyed. On the roof of a building a block up on the other side of the street, in between two graffiti-covered chimneys, a woman gave a man a haircut. Her scissors were cutting his blond locks alarmingly short in the front—I prayed that he had meant to ask for bangs. I fantasized that when she finished, he would look in the mirror, hate her work, and blame her for ruining his life. She would respond coolly, like the barber in Fleabag: “If you want to change your life, change your life. It’s not going to happen up here.” Down the block, a girl, probably eight or nine, pushed kids half her age on the swings. She switched back and forth between two swings, trying to strike each with equal force at even intervals. She gently helped the younger kids out of their swings when it was time and they ran away to hang from the monkey bars. With her job finally finished, the older girl plopped down on the biggest swing, kicked off, and let herself go. I remembered last fall, when the tree across the street had been aggressively yellow, and then, a couple of months later, when I couldn’t stand the sight of its naked skeleton. Somehow, it was budding green, now. Flower petals floated past me like confetti, carried uptown by the wind. One block up, across the street, an old man sat cross-legged at a table outside of the pizza shop. I couldn’t make out his face, but he had been sitting out there, facing the street, this whole time. His head tilted up as he soaked in the new sun and reveled in the quiet.

Illustration by Samia Menon 9

Adam Glusker

BY LYLA TRILLING

In high school, Adam Glusker, CC ’21, was not cast in RENT his senior year. This is significant because, in my mind, Glusker was the lead in every play our showbiz-infested Santa Monica private school produced. On a warm Los Angeles afternoon, over a fermented grain bowl and some sparkling limeade, Glusker corrected my fabricated memories—he never sang “La Vie Bohème” in our black box theater, and he certainly never danced among a group of Angeleno teenagers pretending to have AIDS. In fact, Glusker never got leading roles at all—he was always beat out by a kid with famous parents or a kid who was “skinny and blonde.” Perhaps I was confusing Glusker acting in RENT for Glusker blasting Paula Abdul’s “Cold Hearted Snake” during lunch and dedicating it to our high school’s theater director. Either way, he put on a good show.

This RENT Mandela effect undoubtedly stems from the fact that as a human being, Glusker radiates main character energy. At 6-foot-5, with bleached hair and a unique talent for vocal projection, Glusker takes up space. “Imposing” is how he describes himself. Despite our shared high school and college experiences, our friendship is fairly recent—I can distinctly remember a time where Glusker and I ignored each other in the salad line at Milano’s. But I’ve always been particularly impressed by Glusker. In high school, he directed and produced an ambitious staging of Kenneth Lonergan’s This Is Our Youth, he dominated the stage in The Crucible (—“Did you play a judge?” — “No. The judge.”), and he’s gotten almost every internship I’ve ever wanted (HBO, A24, and Anonymous Content, to name a few). He assured me, however, that he’s had a relatively normal upbringing compared to his industrybred Los Angeles peers: “My parents don’t work in showbiz—I guess you could say that my story is a ‘from rags to indie television’ situation.” Glusker is a recognizable campus figure—aside from his towering physical presence, he’s both a Blue and White-published writer and a former cast member of V125, Columbia’s last in-person Varsity Show. This fact still surprises me—as someone who describes Columbia’s culture as “testicles, vomit, and Virginia Woolf, to use three words,” Glusker does not seem the type to celebrate said culture in a musical-comedy setting. “The thing about me being an actor,” Glusker told me, “is that, like, fundamentally, acting is a mental illness.” Needless to say, V125 is merely a shadow in Glusker’s theatrical past—he has no intention of becoming an actor.

Despite his aversion to the craft, acting and theater have undoubtedly played a major role in Glusker’s life. “A big part of my personality in high school was that I was like, ‘I hate this town’—‘this town’ being Los Angeles, California—‘I’m going to the big city!’ My high school bedroom was literally decked out in the New York City skyline—I had the fucking Top of the Rock view on my wall.” But then, Glusker went to one of those “The city is your textbook!” high school semester programs where instead of living in the Big Apple, Glusker was plopped into the middle off Dobbs Ferry. Maybe Los Angeles wasn’t so bad after all. “Sure,” Glusker told me, “When I was a freshman at Columbia my bio did read ‘LA/NY’ on Instagram … But, I guess, the sort of struggle of my life has been whether I am Beverly Hills or I am New York.”

Glusker is, of course, referring to Bravo’s Real Housewives franchise. He likes the “Aaron Sorkin speed” of New York’s dialogue, but the drama of Beverly Hills, to Glusker, is unmatched. Glusker is utterly obsessed with “The Real Housewives,” a fact that became apparent in his playwriting thesis, R.I.P. Andy Cohen, which I had the pleasure of watching (and then reading, and then re-reading) in April.

R.I.P Andy Cohen, which Glusker described as a “play/cry for help,” uses the real-life story of Glusker and his ex-best friend, whose character is aptly titled “[redacted],” betraying each other “in the spirit of being wholly iconic.” As my roommate and I sat on our couch, watching his virtual performance, it felt as though we were intruding on something deeply personal. There was something perverse about listening to actual podcast recordings and reading real, emotionally vulnerable text messages between Glusker and [redacted]

while the boisterous banter of Beverly Hills’ finest housewives hummed along in the background. Originally, Glusker wanted to create from memory what he remembered about his relationship with [redacted], but it didn’t feel real enough. “That felt bad,” he told me. “I was like, ‘Wow, I don’t really remember this,’ which was sort of like lying and fabricating conversations, which I guess is what auto-fiction writers do all the time—I just felt weird.” So Glusker stuck to the facts: “I knew that I had these audio recordings and I had that text message and those were real. So I started with those. And then, from there, I sort of made a play.” His “sort of” play was exceptional, shocking, and grotesque all at once, and it deservedly received the Robert W. Goldsby Award and the Dasha Epstein Amsterdam Award in Playwriting. I asked Glusker if he wanted to be a playwright, and, to my surprise, he shook his head no. He graduated in April and is starting work at the Creative Artists Agency (“CAA—ever heard of it?”) for the theater department in August. “What then?” I asked him, mockingly. “You want to be a development executive?” Glusker shot me a guilty look—I nailed it. “No! You are selling out!” I yelped. But he isn’t, not really. Glusker would never compromise his integrity or authenticity—everything he does is exactly what he wants to do. He makes one dream of working in corporate Hollywood. But I have my suspicions. In my mind, I know he’ll be a famous playwright. Just like I know, without a doubt, that Adam Glusker played Mark Cohen in our high school’s 2017 production of RENT.

Illustration by Lyla Trilling