46 minute read

Cole Cahill

from May 2022 Issue

Searching for the Activist Ivy

Does Columbia’s political scene today live up to our reputation?

Advertisement

BY COLE CAHILL

It’s a sunny afternoon on College Walk in 2003; the birds are chirping, Lerner Hall still has that new building smell, and the post-9/11 student body at Columbia has politics on the brain. Abram Handler, CC ’07, broke down a typical scene in a Spectator op-ed: Near the sundial is the Spartacus Youth Club, “a wacky clan of socialists who proudly assert to be the party of the Russian Revolution.” Members of the International Socialist Organization distribute pamphlets in Lerner. Lining the brick path of College Walk, protesters call for revolutionary Black liberation and “the defense of North Korea against the tyranny of the United States.”

This is certainly not a Columbia that I’ve ever seen. Compared to this depiction, today’s College Walk seems downright conservative. I keep my eyes peeled for campus uproar, protests, and direct actions, but with the major exception of the Student Workers of Columbia strike last fall, in-your-face political work is a rare sight at this University. Student groups promoting any political cause, let alone groups promoting the violent overthrow of the American state, are few and far between.

The deterioration of radical political activity here is indeed a relatively recent phenomenon. In the decades after the 1968 uprisings, Columbia sustained active chapters of radical student groups—organizations like Students for a Democratic Society, the Student Coalition on Expansion and Gentrification, and Lucha, a radical Latinx student organization, all had active membership through the 2000s. The University’s radical reputation gained national traction, too: In 2006, after student protesters rushed the Roone Arledge Auditorium stage during a speech by the Minutemen, a vigilante border patrol group, Bill O’Reilly invited the president of Columbia College Republicans to debate the editor of this magazine on The O’Reilly Factor. O’Reilly called Columbia the “University of Havana North,” and the leading light of the "left-wing jihad.”

This characterization was generous, to say the least, but it aligned with a politically radical public identity for Columbia ubiquitous in the post-9/11 years. The “activist Ivy” image persists today in Columbia’s and Barnard’s branding—a student I spoke to recalled their tour guide telling them to expect a protest, a counter-protest, and a counter-counter-protest on any given afternoon—but the political climate on campus today is decidedly out of step with that claim. Perhaps more strikingly, the supposed Gen-Z vanguard leading the new era of radical leftwing politics is largely invisible. These are the students who were in high school for Trump’s election, who organized March for Our Lives walkouts; students whose earliest years of legal adulthood were marked by a global pandemic, a national uprising for Black liberation, and an attempted right-wing coup-d’etat of the federal government. December’s Harvard Youth Poll found 33% of Americans ages 18 to 29 considered themselves politically engaged, up from just 24% in 2009. Why, then, is College Walk so quiet? Is the politically engaged, radically bent version of Columbia dead in the water? Have Columbia’s radicals been absorbed by the institutions of neoliberalism?

…

Left-leaning political organizations at Columbia fit into two broad genres, each characterized by their proximity to institutional politics. In one camp are direct action–based organizations like Student Worker Solidarity and Housing Equity Project. While the days of radical flyering on Low Steps are largely behind us, these groups fill the void once dominated by the International Socialist Organization and Students for a Democratic Society. A flurry of direct action and mutual aid organizations, including Mobilized African Diaspora and Students Helping Students, surged in membership and support during the 2020 uprisings and the subsequent remote academic year, but are effectively dormant today.

In the other category are the longstanding groups which tend to work within established political structures and institutions: the Columbia University College Democrats, the Roosevelt Institute, and the Columbia Political Union. These groups intend to be big tents; Roosevelt and CPU both identify as “nonpartisan,” and CU Dems describes itself as “a

space for all people with left-leaning ideas.” It’s not impossible for talk of revolution or disavowals of the status quo to surface in these organizations, but they are each essentially committed to working with the powers that be.

There’s no official or unofficial census for campus club membership, but the most prominent explicitly political student organization at Columbia appears to be the Columbia University College Democrats. CU Dems, as it is colloquially known, is not a radical organization. At their weekly general body meetings, 15 to 25 members meet in a cinderblock-clad room in Lerner Hall to watch a peer-led presentation on an issue of national political concern—taxes, student debt, interest groups, to name a few—before opening the floor to discussion. The conversations are relentlessly lively; hands shoot up after the conclusion of every comment, and the moderator often assigns a batting order of speakers once the discourse gets going.

“In good news, the IRS just got a 6% increase in funding in the Omnibus spending bill, so hopefully, gradually, we will be able to keep people more accountable,” the discussion leader declared at a meeting on taxes in late March. The floor opened into a series of takes about how the federal government can raise taxes on the wealthy—some suggested closing loopholes, others emphasized reforming and funding the IRS. Before long, the congressional elephant in the room materialized: The moderator mentioned that the Senate shot down a proposal for a billionaire tax, only applicable to the nation’s 700 wealthiest people, within a day of its introduction.

“Tax the Rich, as much as it’s a nice slogan, is probably not in the foreseeable future,” a member said.

Of course, any discussion predicated upon changing America through institutional levers in 2022 is bound to run into the problem of congressional gridlock. Even with Democrats gaining control of Congress and the presidency in 2020, the progressive agenda remains at a standstill—recall Kyrsten Sinema enthusiastically thumbing down a federal minimum wage increase and the hollowing out of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act last year. After years of insistence for young people to vote, call their representatives, and march against gun violence, the unrelenting paralysis of Congress has, in part, led to the majority of young people to believe American democracy is failing. In this room, though, people remain committed to pursuing change through the levers of Congress. Members often reminisce about the New Deal and other periods when legislation managed to enact material changes; progress might be at a standstill now, but they believe that one day, with enough effort and strategy, governmental institutions can bring about the sweeping changes the nation needs.

Jacob Kimbarow, GS ’24, is in the room every week. An Air Force veteran, Kimbarow came to political engagement through leadership roles in barracks’ councils and booster clubs while in the service. He exudes a military-style cordiality, and it’s clear he has a few years on his peers in CU Dems. But in many ways, he embodies the ethos of the 2022 college Democrat: He’s adamant about the pressing need for things like student debt forgiveness and universal healthcare, and he laments the out-of-touch Democratic Party establishment for standing in the way of real progress.

“The thing that I have hope for is not for my leaders now, it’s for the leaders that we’re going to have in 10 and 15 years,” he told me. I asked him whether the current state of affairs allows for that kind of time—the climate emergency is coming in a matter of years, not decades, after all.

“That’s the Catch-22 of it all,” he said. “I know when our generation, or our group, is in charge, things are gonna be different, but I don’t know if we can get there quickly enough.”

Kimbarow sees himself as part of a rising generation of reformers that will steer the nation in the right direction—once it gains control of the reins of power.

“If I’m having a conversation with Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the House, I have to act as if Nancy Pelosi’s having a conversation with the future Speaker of the House. I have to say that this party belongs to me, too. I don’t like the way that it’s going, I will be invested, and I’m going to annoy you. I’m gonna irritate you until I’m in charge,” he said.

Kimbarow’s approach does not represent every member of CU Dems; others have more tepid relationships to national Democrats and national politics in general, but still place their efforts in institutional approaches. Nikita Leus-Oliva, the president of CU Dems, a former organizer for the Biden 2020 campaign, and former intern for the DNC, doesn’t consider herself a capital-D Democrat these days.

“There are a lot of things that need to happen that

Illustration by Hart Hallos

are destined to be blocked by the political system that we currently have, because it was meant to do that,” Leus-Oliva said. “And at the same time there has never been a time that we need these things more. I think it’s a matter of changing the system; it's hard to try to fix a system when you’re still in the system.”

Talking to Leus-Oliva, I can sense that she recognizes the difficulty of reconciling her clear-eyed awareness of the need for structural change with the futility of the federal government in practice. It’s common for politically engaged young people to recognize the Sisyphean nature of electoral politics; their disillusionment with the system grows with each campaign and organizing endeavor, but they feel obliged to continue pushing through the available means. Leus-Oliva is steadfast in her will to push onward.

“I honestly think nothing short of revolution can bring a new system,” Leus-Oliva said. “So if we’re not organizing a revolution and we are still working within the system, we need those big sorts of changes.”

This attitude is shared by numerous members of CU Dems, who see engagement with “the system” as complementing, not contradicting, their support for radical politics. They see many of the self-professed radicals as effectively inactive—talking a big game about the uselessness of political work without engaging in any real alternative. To Sarah DeSouza, the club’s president during the 2020–2021 school year, that phenomenon pervades white Columbia students who stake out radical political positions.

“These are not people who are reading the Black Panther Party’s texts,” DeSouza said.

“It just very much feels like talking points and no action. Even if you don’t want to be a part of CU Dems, there are tons of ways to be involved in New York City.”

Much like her presidential successor, these days DeSouza finds herself feeling distant from the Democratic Party, and the gulf between her belief in abolitionist politics and the party’s moderate platform has left her feeling further from traditional political engagement than at any point in her life. Nevertheless, she tempers her disillusionment with the belief that policy and legislation remain viable avenues for change—in fact, some of the few tactics on the table for college students. “With the resources that we have, that's kind of what we are allowed to do,” she

said.

The organization’s own means of putting beliefs into action are primarily their two annual excursions out of Morningside Heights: a campaign trip each November, in which members canvass for Democrats in contested elections, and a spring “lobby trip,” when they take a bus to Washington, D.C. to advocate for congressional bills.

The term “lobbying” is inextricable from its real-world reputation as a technically legal form of bribery. But rather than promising campaign donations, Dems members travel to Capitol Hill to earnestly attempt to persuade members of Congress—or, more often, their staffers—to support or co-sponsor legislation. This year, participants prepared talking points for legislation like the HALT Campus Sexual Violence Act of 2021, and a bill to federally replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

While at the Capitol, the students rarely waste their time with Republican representatives who categorically oppose anything within a 10-foot pole of the Democratic policy agenda. But as they lobby Democrats, the members confront the slim odds that their bills become law: Even if they manage to convince every elected Democrat, the Senate filibuster makes even the most minor legislation require Republican approval. Objectively, the odds of their lobbying impacting legislative outcomes are slim.

But Leus-Oliva thinks that’s okay. To her, the purpose of the lobby trip is to build community and educate members about legislative advocacy—moving the needle on legislation is an added bonus.

“Some bills, like Build Back Better, are never going to pass. It doesn’t matter who talks to who about it. It doesn’t matter. It’s not going to pass,” Leus-Oliva said. One group of students, she told me, still chose to lobby for Build Back Better.

Most of the club members, including Leus-Oliva, have no illusions about their influence over the Democrats’ agenda. “We are just a College Dems club, we’re not the Democratic Party. We’re not D Trip”—the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, that is—“we’re not any of these huge organizations. We’re not Joe Biden. We don’t need to put the pressure on ourselves to pass these bills,” she said.

“I think almost everyone that I spoke to after the trip said that they left the trip feeling like they have a real community and that the Dems community has been solidified—that to me is a better metric of success than what happens with the bill itself.”

Henry Magowan, CC ’22, a co-founder of the Gravel Institute, disagrees. Magowan has focused his energies squarely away from Columbia’s campus. As part of the team that ran Mike Gravel’s 2020 far-left presidential campaign, his political efforts garnered national attention during the primaries. He and his collaborators, Henry Williams, CC ’23, and David Oks, transitioned the campaign into the Gravel Institute, which focuses on producing left-wing political educational videos, last year.

To Magowan, the CU Dems lobby trip serves to legitimize a broken political system without materially influencing legislative outcomes. He sees Democratic officials as fundamentally unresponsive to the demands of student political organizations.

“This is just how the DNC operates. They tell you that they're listening and that they care about the young Democrats of America, but they basically fool you with taking the meetings in the first place,” he said.

The lobby trip, in his view, isn’t merely ineffective—it reinforces a counterproductive and inherently regressive approach to student political action.

“I struggle to provide you examples of the insider track being successful,” he said. “And once you get your foot into the Democratic Party and its entire apparatus, it is so easy to slowly see yourself pulled to the center, pulled to the right. That’s just how these things work.”

Lula O’Donnell, BC ’22, a member of Student Worker Solidarity, expressed a similar view. “There’s a constant pull of liberalism defanging radical movements. As a student organization, I definitely think that we have so much work to do locally,” they said. “There is so much power to be built right here that I don’t really feel a need to go to Washington, because all of the power we need to make these grand changes we already have.”

This semester, O’Donnell helped lead the revival of Student Worker Solidarity, a group originally coalesced in 2012 to organize undergraduate student solidarity with labor unions at and around Columbia. The group fell inactive during remote learning and remained defunct during the graduate workers’ strike last semester. The widespread support for the strike motivated O’Donnell to help reestablish a space to organize campus unions and leftist projects, including efforts in the greater community. Recently,

SWS is working to connect Columbia students with the organization United Front Against Displacement to help oppose the privatization of the Harlem River Houses and other New York City Housing Authority complexes.

The fledgling group’s meetings are small, with about a dozen loyal members descending into a Pupin classroom each Monday night. But SWS is not alone in looking to channel more direct forms of political action outside of Columbia’s gates. Housing Equity Project combines outreach to homeless residents of Morningside Heights with advocacy for housing justice in Upper Manhattan, with particular emphasis on mitigating the gentrifying impacts of Columbia’s expansion into Harlem. Rebounding after a pandemic hiatus, the organization counts around 40 active members across its outreach, shelter staffing, and advocacy initiatives.

When Sam Howe, CC ’24, transferred to Columbia from Amherst, he expected the “activist Ivy” reputation to hold water. After seeking involvement in a general leftist political group—he emailed the YDSA chapter but heard back over a month after the fact—he found the student group working on political and community-based work that most compelled him was HEP.

“I think I knew that no matter what I’m coming to a rich institution that has a vested interest in keeping its student body alienated in some sense from the community around it and from serving that community. So I had no aspiration that I was coming to a school full of people who had the energy and time and motivation to constantly work and be activists,” Howe said. “But I was also disappointed to some extent to find how many people, at least who seemed to me, had little to no interest and did not do much reflecting in terms of their position in terms of the community.”

It’s meaningful that Howe found that HEP was the home of the political work he had in mind when he arrived at Columbia—it indicates a larger trend of leftist campus politics focusing more on systems around the University rather than working to change elements of the literal undergraduate experience.

Among students active in groups like HEP and SWS, there exists a sense that the best use of their political energies is supporting the people and communities grappling with the harms of Columbia’s institutional policies, whether that means rallying students to support a picket line for higher wages or organizing against the University’s role in pricing out Harlem residents. For better or for worse, the political culture of protesting campus speakers has fallen out of favor, and large-scale movements against campus sexual violence have faded out of the limelight—Take Back the Night, which was for decades one of the largest protest events at Columbia, was not even held this year. Today, the attention of Columbia’s leftist set is increasingly turned toward the material consequences of the university they attend.

It’s hard to know whether that shift places the era of communist flyering and internal protesting behind us—after all, the YDSA tuition strike garnered thousands of signatures demanding improved undergraduate learning conditions during the 2020–21 school year—but the classic objects of progressive campus politics are decisively not drawing widespread participation. DeSouza recalled a day this semester when anti-abortion protestors demonstrated on Barnard’s campus without drawing largescale opposition. To her, that lack of urgency signals a complacency toward forces of oppression among Columbia and Barnard students.

“I have not seen any articles about that protest. I’ve not seen any talks about that protest. The fact that it was happening outside of our front gates—it’s a typical example of [how] we are complacent in our own oppression,” DeSouza said. …

The two-year anniversary of the national uprising for Black lives, with its widespread radical demands for the abolition of police forces and reimagining public safety, is approaching. The memory of that summer, when the racist violence baked into our institutions demanded uninterrupted attention, had not dissipated when Columbia’s physical community reconvened last fall. As the academic year comes to a close, the momentum of that summer and the urgency to demand a new system hasn’t produced a new 1968. But as established organizations interrogate their approaches and newer groups set out to organize the student body, perhaps this is a moment of transition for political work at Columbia.

“People here are really smart, but I think people also need to be provided with more political education that is actually geared toward action,” O’Donnell said. “We need to collectively figure out how to not let homework get in the way of meaningful political change.”

Butterfly Effect

Control, chaos, and conversion in the Uris Pool.

BY SONA WICK

My first experience in the Uris Pool was one of abject humiliation. It was November 2021, and I had never put on a swim cap before. It’s no intuitive task. With the added pressure of the chuckling grad students not-so-subtly watching me, it took about 10 minutes to accomplish the measly result: ears out, accompanied by a few exhausted strands of hair. Smeagol-like, I waddled out of the locker room.

In the water, I realized that, while able to swim, I knew little of “strokes.” Freestyle: exhausting. Backstroke: disorienting. Butterfly: not even close. I settled on an extremely slow breaststroke, keeping my head above the water. Despite feeling ridiculous, I swam about once a week for much of the fall. I never stayed for longer than 15 minutes, and most of that time was spent catching my breath. I viewed the Uris Pool with detached (likely defensive) irony: a strange hovel where I went to exhaust and embarrass myself. It merited little serious thought.

A day after moving in for the spring semester, a mirror fell on my head. Two hours later, I fainted (likely because of the mirror), leaving me with double head trauma. Every concussion is different— some combination of visual, auditory, or vestibular effects—and mine happened to unravel the link between my eyes and brain. Any visual stimulation, including looking at a screen, reading, or peering out too bright a window, would send me into hourlong bouts of nausea and headaches.

For the first two weeks, I lived in constant terror that my brain would never be the same; most days it felt like a mush sloshing between my ears. I felt fragile. I became incredibly superstitious, obsessed with cracking the sequence of seemingly arbitrary events that led to the fateful one—perhaps if I had

Illustration by Taylor Yingshi

properly recycled that takeout container, the cosmic overlords wouldn’t have tipped over the mirror. I struggled to understand how events I had no control over could uproot my life so quickly. How do I rely on a sense of stability? How do I stave off chaos? Is the world governed by raw entropy, a cavernous maw of randomness set out to slowly devour us? I saw a comrade in Murphy, his namesake law my new credo.

I returned to school slowly, painstakingly, over the month of March. When my brain finally felt solid enough, I became more motivated to exercise than I’d ever been before. I was aware of the complex behind it: Losing control over my body made controlling it feel especially gratifying. My new routine involved one to two hours at Dodge every night, half that time spent in the Uris Pool.

After a while, my disjointed breaststroke of yore evolved into something comfortable. I started to swim in uninterrupted intervals so long that time melted away. I felt like an Alka-Seltzer tablet dropped into water, dissolved and purposeful. In the pool, the concussion and its associated anxieties melted away. I was in control of my body, mind, and environment. What was formerly a mundane pool became a sacred space, a shrine to order’s triumph over chaos.

I started to wonder what was behind the mystical experience I had had, whether there was something uniquely meditative about the Uris Pool. Was I alone in finding it a special place, or did it affect other users similarly?

…

Its formal name is the Percy Uris Natatorium. Aside from some light cosmetic changes, it has stayed the same since 1974. On a given day, the pool is occupied by a wide array of characters, all of varying degrees of talent: The varsity swim team meets as early as 6:30 a.m. onto 9, and sometimes in the afternoon; the Beginner Swim PE class (mandatory for those who fail the swim test) meets sharply at 9 a.m.; recreational swim is afternoons and nights; club teams take over past 9:30 p.m. and practice late into the night.

Recreational swimming is open to anybody with a Dodge Fitness Center membership. Lucy Arico-Muendel, BC ’23, lifeguards at the pool three times a week. She enjoys the crowd’s unpredictable composition, which consists of undergrad and graduate students, professors, and the oldest man you’ve ever seen. The pool fosters a fusion of socialization and athleticism, and a heartening cultural synchronism between faculty and student life.

Then, of course, there are the seniors taking their swim tests. They’re easy to spot: often giggling and in gaggles, anxious to complete Columbia’s most infamous exam. Those who fail must take Beginner Swim with James Bolster, head coach of the men’s swimming and diving team. Bolster spends his days toggling between Olympic-level athletes and students that failed to swim three continuous laps—a combination I found incredibly charming.

Bolster’s pedagogy seems just as much mental as it is physical, focused on building his students’ confidence as much as their swimming ability. “They start, they’re petrified, they don’t even want to get in the water. By the end of class, they’re completely comfortable and they really feel like, ‘Wow, I got a skill.’ It’s wonderful for their self-confidence, and it’s really a class that I enjoy teaching.”

Lifeguards monitor these classes as well, watching students improve over the course of a semester. “I’ve seen a few swimmers from the classes come back during rec swim,” says Arico-Muendel. “This one guy even went above and beyond and learned butterfly, even though that’s not necessary.” …

These stories I found heartwarming, but I needed to dive deeper: What about the pool felt so profound to me?

Most people I spoke to noted the location of the natatorium, buried four floors into the already subterranean Dodge gym. “I don’t want to be four levels underground,” says Arico-Muendel. “It’s a little miserable … if we drilled into any one of the walls, what would we encounter? The subway?”

Her comment evokes either claustrophobia or perhaps some sort of reverence: Trudging down all those stairs feels like a pilgrimage to the core of the earth. The pool becomes a sort of cavernous, echoing pond. Stalactite cones protrude from the wet floor while stalagmite flags hang from the ceiling. I thought this, at least, until Coach Bolster burst my bubble. “It does seem like it is four flights underground, but in actuality when you are down on the pool deck you are on street level.”

Deep (or perhaps not so deep) below the earth, Newton’s fourth law reveals itself: No one looks hot in a swim cap and goggles. It is truly incredible that the most collectively naked spot on campus hap-

pens to be by far the least sexy. However unappealing as it may sound, I’ve found that looking like a prenatal alien around my peers is oddly liberating. It changes the social pretext. Bald, vision-impaired, and suspended in fluid, we return to an embryonic state—the pool a communal womb on whose walls we kick and spin. In utero, we cast our focus inward. “It’s an activity that promotes this introspection,” says Coach Bolster. “The opportunity to sort of immerse yourself and get away from the rat race.”

In my conversations, I found that many people experienced the timeless effect of swimming that so moved me. Coach Bolster seemed to share my reverence for the water: “It’s an incredible form of meditation … You hear the rhythms of your own body, you have this sense of freedom to do whatever you want. You're in charge of everything.” I was surprised by how closely his description recalled my own experience of swimming as a means of control.

While Arico-Muendel doesn’t often swim in the pool, she told me she experiences a similar meditativeness from the stand. “When I’m watching I have to put my phone down and stare straight ahead … I let my mind wander. With the lap swimmers, it’s almost relaxing to watch them do the same thing over and over again. I know it’s relaxing for them, so I’m sort of experiencing that secondhand.” …

A week ago I was swimming a slow backstroke, jellyfish-like, and contemplating this very article. The blue and white tile like … the flag of Denmark? like Chani’s eyes? Enwrapped in meditation, I lost my grip on spacetime and bumped headfirst into the wall. I felt shocked and betrayed by the Percy Uris Natatorium: After all my dedication, this is how you reward me?

I remembered something Coach Bolster told me about his experiences freewater swimming. “There’s this wonderful sense of freedom, freedom of expression. It’s you and nature, and to a certain extent, you’re controlling nature.”

Up until that moment, I agreed with him. I felt that, through extreme bodily discipline, I could somehow warp the world around me to my will. While swimming, I felt impenetrable. Yet as my head smarted through my swim cap—a much more benign version of the pain I had endured months ago—I realized that disorder is unavoidable and that sense of control is illusory. We all age. We all suffer damages.

I sought to understand what made the pool special, but I came to recognize its universality: a microcosm of the human propensity for imposing arbitrary structure to preempt the chaos we most fear. We place lanes for people to swim in, station lifeguards to watch over us. We perform our daily regimens with machine-like repetition. The pool is a tamed reproduction of oceans, lakes, and rivers, those bodies which fall under the unpredictable domain of mother nature. The water is so chlorinated that, according to Arico-Muendel, “Covid can’t survive a foot above the pool.”

But as hard as we try, water simply cannot be forced into our prescriptions of order. Randomness increases as atoms are given more freedom to roam around. Liquids are governed by more chaos than solids are, but less so than gasses; in that sense, their fluidity provides a sort of entropic middle for humans to explore. Above ground, we are crushed by the weight of gravity, academic expectations, and bookbags. In the water, we experience the foreign freedom of the liquid state. We may attempt to mitigate the pool’s water with buoys, safety precautions, and goggles, but we can never truly control it. Water is consistent in its entropy, just as chaos is reliable in its pervasiveness.

In Paradise Lost, chaos is an enemy of creation; yet hasn’t Darwinism shown that the two are one and the same? The world is indeed governed by raw entropy, but that entropy is creative just as much as it is destructive. The invisible hand that tipped over the mirror also, perhaps, placed me in a class with a future close friend. There’s no use fearing chaos; in many cases, it deserves our welcome.

Once more, I looked around the Percy Uris Natatorium: two students moseying by on flotation pads, talking about their day; an undergrad thrashing past an old man; a woman treading water in perfect equilibrium. An ecosystem of its own, a primordial soup of human limbs, naked, in slow-motion.

Staring chaos in the face, we can either cower in fear or continue living. When students of Beginner Swim stand at the pool’s edge gripped with fear, Coach Bolster’s job is to talk them in. “The water will support you if you let it,” he told me. “Important that you respect it, but not that you fear it so that you’re afraid to jump in.”

Oh, The Places You’ll Go!

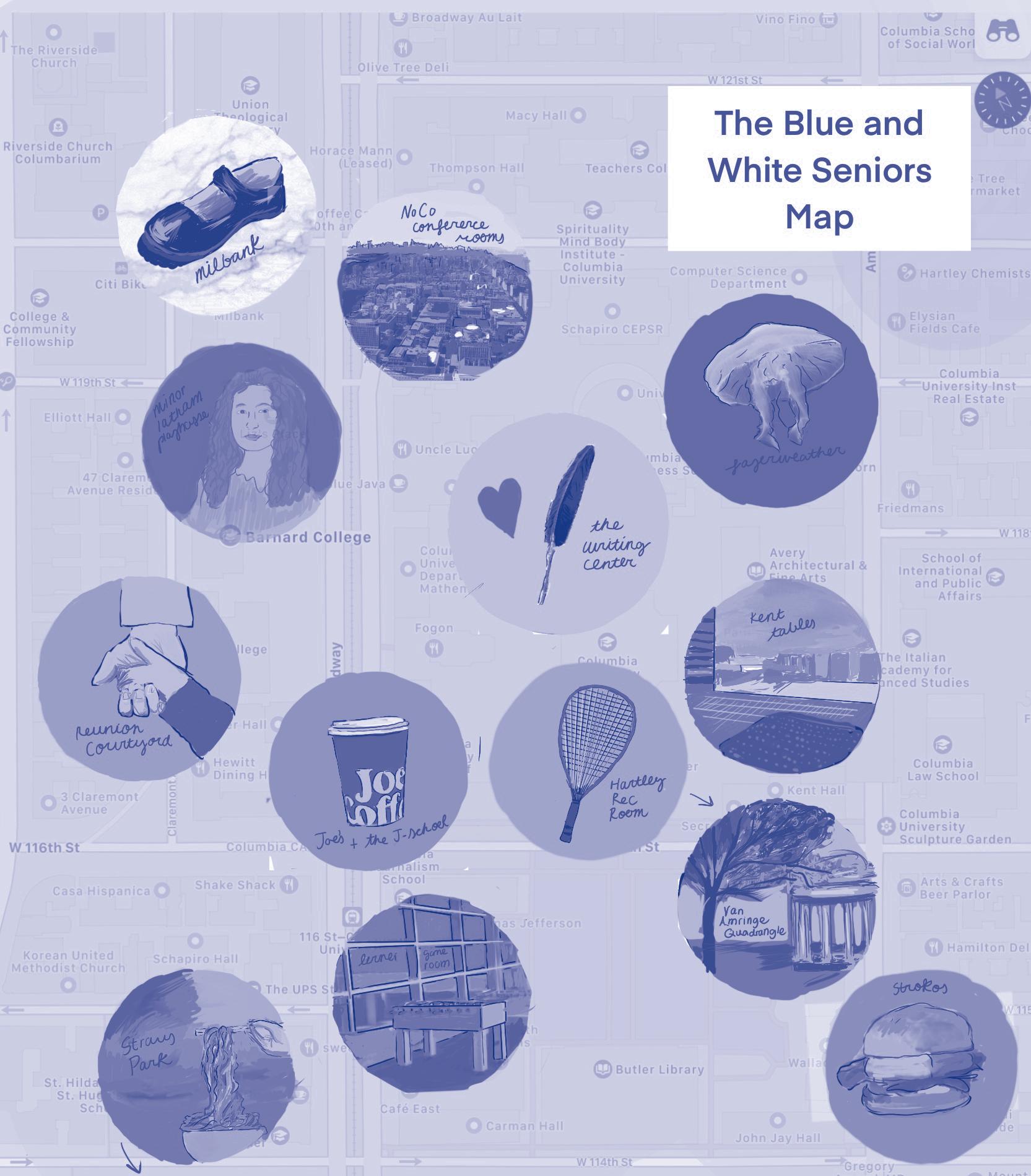

The class of 2022 is the only grade that experienced a full pre-pandemic year on campus. As they prepare to leave, our B&W seniors pay tribute to their choice spots on campus.

The Van Amringe Quadrangle Lodged between Hartley and Wallach.

Here at Columbia—the greatest university in the greatest city in the greatest world in the greatest galaxy—we don’t waste time with silly titles or epithets. Always on New York time, we talk quick; with no syllables to waste, our school has a great penchant for portmanteaus. If I heard someone say “Northwest Corner Building,” I would have to assume they referred to some mythical establishment, certainly located in NYU territory. Instead, we do NoCo. We do ButCaf. We do HamDel, LitHum, FroSci—even UWriting is shortened by four iambs. Nearly everything here has a catchy name. Emphasis on nearly.

It wasn’t until my senior year that I learned even my secret, hidden, indie, favorite spot on campus had a title. The Van Amringe Quadrangle sits between Hartley and Wallach, a sweet rotunda which, according to our school website, “is best used for barbecue or tabling events.” Don’t let the admin fool you—this spot is Cool, capital C. Freshman year, relegated to a life off the grid in a Hartley single, I noticed every manic pixie dream girl and their respective Cocteau Twin–boyfriends stood around the Van Amringe Quadrangle smoking cigarettes, laughing at the loser simpleton Nietzsche. Lonely and isolated, I took the suave insouciance of my fellow Hartley hostages to be a badge of pride. Not all hope was lost: I, too, could evade the sickly and socially inept stereotype of a Hartley resident. Hope resided in that quad, and she resides there still. Check it out one day; I promise you no one has heard of it before, mostly because the Van Amringe Quadrangle is a super long and super stupid name.

—Chloë Gottlieb

The Northwest Corner Conference Room(s) A (conference) room with a view.

Campus was porous in the spring of 2021. As we were forbidden from entering the living quarters of others, my “roommates” were those with whom I snuck into abandoned lab spaces and claimed squatters’ rights over empty classrooms. We learned which doors were kept ajar, which could be coaxed open with a tap of an ID, which would submit to a jerk of the arm. Before we knew that the door between Pupin 11 and NoCo 7 was “yankable,” we needed the elevator. As it rested on ground level, we’d pray for a stranger on a restricted-access upper floor to unwittingly summon us up. With such tricks now sealed off, my only access to the conference room at the top of NoCo is through fragmented memory—details stitched together into a tattered quilt of recollection. There are, for instance, actually two conference rooms, but I remember only a single corner framed by two walls of floor-to-ceiling windows that thrusted the entirety of Manhattan upon anyone who entered. I cannot now produce a mental picture of the view, which stared down at the roofs of every other building on campus, but I can still hear the muted gasps that emerged from the lungs of those staring at it for the first time. I remember that in April, I camped out in the room for one of two consecutive nights I spent awake finishing a term paper—though I cannot remember which of the two it was. I don’t remember when at night my friends came, bringing Sweetgreen and welcome distraction, but I do remember that I saw the sunset and the sunrise alone. I don’t remember what shade of purple set itself atop the dimming horizon, or exactly what it felt like when the first ripple of light crept over northern Queens. But I remember that I was listening to Mort Garson at the beginning of the night, and Ambrose Akinmusire at the end. I remember that at 7:30 I took a last sip of the skyline and left for Hungarian in search of caffeine. I don’t remember if I ever went back.

—Cy Gilman

Strokos A contemporary eatery with perspective.

My biggest regret from my time at Columbia is something I did too late. What can you,

dear reader, do earlier than I to avoid this feeling of remorse, you ask? Go to Strokos sooner than your second semester here. Actually, go on move-in day. Take your family and show them the beauty of Columbia.

To me, Strokos is a mythical place. To others, it is a Greek deli on the corner of 114th and Amsterdam. While it is technically outside of the gates, I consider it part of my campus. In fact, it is the center of my campus, if you measure these things in terms of frequency of visits. Conservatively, I go to Strokos four times a week. I approach the counter and I order my classic: a bacon, egg, and hashbrown on an everything bagel, no cheese, please. The cost of any item at Strokos varies by the day, and that’s just the way it is. As frustrating as that may be, you won’t remember it when your teeth sink into the best bagel north of Absolute. There’s a reason their tagline, proudly displayed on each of their shirts, reads “A Contemporary Eatery with Perspective.” So go to Strokos, and stop eating at prehistoric cafes with simple-minded outlooks.

There will always be haters. To preempt them, I say this: Strokos is better than HamDel. If you disagree, fuck you. HamDel will make you cry, Strokos will give you a feeling of ecstasy like nothing you’ve ever felt before. HamDel is disgusting, Strokos is ethereal. HamDel is chaos, Strokos is grace. —Daniel Seizer

Joe’s and the Journalism School Between fact-finding and home.

There is absolutely no good reason why the coffee shop attached to Pulitzer must be called Joe Coffee and not, simply, Joe’s. I have added the possessive ever since my first day of classes, when I was sitting in the journalism school lounge reading for Romanticism and a barista wandered in, offering free cold brew. I had not ever enjoyed coffee prior to that fateful day, but took a bottle for appearance’s sake. Unaware of my toddler-like tolerance for caffeine at that time, I finished the entire bottle and promptly struggled not to fall down the stairs as I walked to my seminar.

For reasons I can’t explain, I made the journalism school a home freshman year. The one-room, one-table library is slightly pathetic, the lounge has comfortable couches but little convenient table space, and the lighting is quite consistently bad. Nonetheless, Joe’s and the J-school were a bustling somewhere for a freshman unsure she wanted to be anywhere at Columbia at all. It helped that there’s a line in The Newsroom alluding to a “hot-shot EP out of Columbia J-school.” (Wanting to be an Aaron Sorkin character is a significant part of my personality.)

My presence in Joe’s soon became a joke among my friends. In Joe’s I’ve marched through paper after paper, read book after book, and struggled through avalanches of equations. I got coffee there nearly every Monday and Wednesday morning before Andy and I strode to Gulati’s Principles. I interviewed the fiery-haired rockstar that would play a lead in the only play I’ve ever written. I’ve doubled over with sobs, overcome by the sly demons of my future-faced imaginings. I’ve nursed a fleeting, obligatory crush on an anonymous barista; he wore beanies and baggy pants and seemed to care about my days. I’ve half-yelled with laughter as Sophia and I people-watched and tried valiantly to get work done. They used to have doughnuts. I bought one each for three of my friends on my first Valentine’s Day here. They don’t have them anymore.

Joe’s is not romantic. It has none of the secluded, literary charm of Hungarian or Max Caffe. It is stark and gray and no-nonsense. The brightest thing against its slate backdrop are the people and the mixed-up chatter of their mixed-up lives, brought together for a moment in the space between fact-finding and home.

—Elizabeth Jackson

The Lerner Game Room A work-free zone.

Ispent most of my first year of college trying to find someplace to sit. If Columbia students have taken one thing from New York City, it’s an enthusiastic embrace of squatters’ rights: If I see an EcoReps water bottle and a Marx-Engels Reader on a ramp table, I know it’s safe to assume that my Ferris biscuit and I are not welcome.

This is the only way I can think to explain the stunning amount of time that I’ve spent in the Lerner Game Room—in the child-size chair between the air hockey and foosball tables, naturally.

When you enter the Lerner Game Room, a sign by the door announces that this is a place for play—“a work-free zone!” I interpreted this rule loosely. By this, I mean that, once situated at my 21

Illustration by Brooke McCormick

perch, I did my homework playfully. By that, I mean that when those rare brave souls actually began a game of air hockey, I quashed my knee-jerk reaction: Hmm … the clang of those pucks sure does make my ears ring. Who was I to put a damper on their institutionally sanctioned fun?

Perhaps this haunt would never have become a habit had my best friend Elizabeth not also recognized its unexpected charms—its vibrant atmosphere, its ample seating, its multiple outlets. We could sit there for hours, talking over the murmur of a Family Feud marathon. It turned out to be one of those friendships where it didn’t matter where we decided to go.

The other day, I returned to our space of choice for the first time since the pandemic. I immediately texted Elizabeth to declare that I had entered a work-free zone. I didn’t have to say more: “grace grace grace. did you go to the lerner game room without me?”

It wasn’t the same, I told her. It’s hard to play foosball alone.

—Grace Adee

Milbank A decidedly good building.

Last year, somewhere on 108th, from the confines of my light-deprived fifth-floor walk up, my roommates and I sipped espresso, chatting about what we missed about campus and hated about our apartment. As we caffeinated, we rebuilt a year lost, mapping memories to corners and corridors. Time after time, I found myself returning to Milbank.

“A good building should feel alive,” I told my roommates, between sips of Café Bustelo. “A good THE BLUE AND WHITE

building should have cracks and character, bricks and books, and ideally a stained-glass window.”

This year, I find myself returning to Milbank, a decidedly good building. Each morning, I mold my Doc Martens into the marbled stairs, hollowed by the kitten heels and Mary Janes of Barnard students past. Sunsoaked in the corner of the classroom, I daydream to the clangor of church bells and coos of the pigeons, gazing through the dusty windows that frame Riverside like a postcard. I may even stick my hand out the window, tracing my nails across the mossed and scalloped edges of Spanish tile, wrapping my fingers around the curled stems of ivy vines. If I’m running late, I run a minute later to pause and admire the Kehinde Wiley portraits, even if just for a moment. Some rush by, studying for years without a trip to the rooftop greenhouse or a moment on the benches under the trees. But I prefer to pass the time on windowsills and benches, remembering that I am alive and in a decidedly good building. —Hailey Ryan

The Hartley Rec Room (HRR).

The day I discovered the Hartley Rec Room was the day my life at Columbia really began. Some people might tell you that Amsterdam Bridge, or Low Rotunda, or maybe even the Van Amringe Quadrangle are the gems of this campus, but these people are ignorant. These are people so taken by the veneer of campus beauty that they overlook the true nucleus of Columbia life. With two pingpong and two pool—billiards—tables, Hartley Rec Room (HRR) is simplicity, it is convenience, it is coziness, it is joy, it is youth, it is fun. When I say to people nowadays, I’m off to play pingpong, they look puzzled. “Where?” they ask. To that, I say, “If you haven’t broken cue in the Hartley Rec Room, what have you been doing?” Hartley Rec Room is post-Macro-midterm solace, it’s a racket sport cardio workout, it’s friendship and it’s heartbreak. There are people out there who think of pingpong as a “mini version of tennis” or “not a real racket sport,” but these people haven’t experienced the HRR endorphin rush. When I’m smashing a looper or feigning a flick shot, I think back to racket sport legend Billie Jean King’s inspiring advice that “champions keep playing until they get it right,” and I think, No, pingpong is a champion’s sport. Pingpong isn’t “mini tennis”; tennis is mega pingpong. And if that isn’t a metaphor for something, I don’t know what is. —Jaden Jarmel-Schneider

The Minor Latham Playhouse Have you seen Mike or Greg?

If my ghost haunted the halls of this campus (and perhaps it already does), the apparition of a curly-haired girl wearing rubber boots would weave through the wings of the Minor Latham Playhouse. Ghost tours of the future would list sightings of this phantom—pushing a set of double doors open with her feet while balancing two armchairs on her shoulders, running up the basement stairs in search of a key ring, echoing, “Have you seen Mike or Greg?” as reported by witnesses, or trying on an assortment of earth-toned vests and pastel pants. She would sit in the darkened dressing rooms when in need of a breath, a rest. Her knees would be dusty from rummaging through the rabbit warrens of Milbank Hall, hauling furniture and hand props. Turn any corner and there she may be, drilling stubborn screws, swagging crimson curtains, casting shadow birds on the wall, or running lines in haste.

The story they would tell, these ghost tour guides of the future, is of a girl who staked her claim straight out of the gate. Eighteen and eager, she wore pigtail braids and gingham, danced as a troll and traipsed as an orangutan. At 19, she mopped watermelon guts and chocolate blood from the floor. At 20, she sat on the corner of the stage, joining an impromptu chorus of “Mr. Blue Sky” in a play that proved spookily portentous of the quarantine to come, and cinematized a disco in Cork. At 21, she greeted fellow ghosts in empty red seats. At 22, the stage was hers to share once more; she crossed the Mediterranean Sea, grew from lad to lady, sprung from an Elizabethan age to modern ecstasies, “about to understand …”

Every night the ghosts gather around the lone lamp center stage. Mine, I suspect, will join the ensemble of that prestigious crew. Theaters are spaces built for ghosts, for surplus stories, and so a part of me will always linger in the MLP.

—Maya Weed

The Writing Center Its warmth comes from its people.

The Writing Center is the only place on this campus that I would not watch burn. In fact, if the Writing Center was (god forbid) burning down, I would run inside and burn with it.

I, like many anxious first-year students, stumbled upon the Writing Center out of fear—specifically, fear that I wasn’t as intelligent as my peers, a status confirmed or denied by the grade I would receive on my first LitHum essay. My analysis of oak trees in the Iliad earned me a 78%. But I continued to visit religiously—not least because I believe my session with Elizabeth transformed a D paper into a C+ paper. Rather, my visits were spurred by something other than letter grades: It was warm. Not literally—as we all know, Columbia’s electricity is crap. Its warmth comes from its people.

If you skip up the steps to Philosophy and make a sharp right turn upon entering, you’ll find yourself at the wooden doors of 310. You’ll be greeted by John—not verbally, only through subtle eye contact—who sits snugly at a corner desk, broadcasting heavy metal hits on days electrocuted with rays of sunshine and smooth jazz on those overcast by gray skies. Jason will probably arch his eyebrows above his desktop, shifting his gaze from the master scheduler—or the pixelated image of a plump dorayaki that consumes his screen—to check in on you. His soft gaze, combined with Kip’s contagious laughter, tells you it’s okay to tip-toe further in.

So you take a seat at the communal table, snag a fun-sized Snickers bar, and maybe flip through a few old New Yorkers before your session. You listen to the consultations happening around you: “Let’s imagine that you’re putting these writers in conversation with one another”; “I hear you saying this … does that align with the intentions of your project?” among many absurd phrases that make writing sound like building a personalized amusement park. Then, when you’re scanning the walls, pausing on the miscellaneous party bags that have been cast as room decor, you’ll realize what you don’t hear: “right,” “wrong,” “good,” and “bad.”

When it comes time for your session, you think you know what to expect: warmth. But warmth arrives in varying degrees. Bridget will ask you about your life’s story. Helen will make a day-by-day plan with you. Ellie will make you laugh. I will offer you tea. So even if you look outside to find the fiercest storm brewing, you know you’re warm. —Nicole Kohut

The Kent Tables Have a surprisingly good cry.

This city, with its practically infinite experiential offerings, crucially lacks one thing: places where you can be both alone and outdoors. Throughout these four years, I’ve lost count of how many moments necessitated such an environment—times when I needed to be in the open air but loathed the possibility of entanglement in a dreaded stop-and-chat. It often feels like Columbia’s campus is too small to even walk from Lerner to Pulitzer without brushing shoulders or making eye contact with someone you recognize.

The closest to this ideal of solitude I’ve found on campus is the row of tables across the entrance to Kent. If you time it right, you can avoid the mass exodus of students to/from East Campus during the passing periods between classes. If you really time it right, you can find the perfect vantage point to see lower campus baked in the orange glow of the late afternoon sun. Read a book. Write in your journal. Have a surprisingly good cry. Enjoy the sublimity of the moment.

—Rea Rustagi

Fayerweather The product of class struggle.

In college I learned that the disciplines were invented here. They probably shouldn’t have been, but they were, so we might as well have fun being inside of them. Lucky for us that they each have a building—we can really kick around.

So I kicked a little, and in college I learned that Avery is a hearth, a mound, a roof, and walls. The point of the sixth floor of Philosophy is to dramatize, dramatize, dramatize, and the point of the seventh is to develop an analytic of power. Casa Hispánica is the origin of modernity, no matter what Maison Française tries to tell you. Schermerhorn’s highest calling is to give deep, ecstatic pleasure— Dodge’s, too. Both are miracles of consciousness, which is sometimes individual and other times collective.

I am quite confident that Fayerweather is the

product of class struggle. Inside, my freshman year, a professor wowed me. Her speech patterns made me think of a jellyfish pumping itself up from the depths of the cartoon sea: out, in, out, in, out, in. Now, I secretly give people the jellyfish test. It’s not standardized, and it’s very difficult to grade. People who pass it are worth keeping around. I think I’ll continue to give it for a while longer, after college. —Sam Needleman

Straus Park Looking toward home.

Iarrived in Morningside as a sophomore, just a semester before Covid began. Living in an apartment on 110th, I knew little about the dorms and quads and buildings of Columbia and Barnard. I navigated to appointments and new classes with a campus map on Google Images, zooming in on bold blue names. In the afternoons, I walked home from class by St. John’s on Amsterdam, passing the community garden on 111th Street, and along Broadway, the Duane Reade, the shoe repair shop, the flower shop. I had no ties to either campus, and little connection to its students. I felt, rather, a warmth for the neighborhood, which I still knew only for its pedestrians, dogs, buildings, and surrounding sidewalks.

Before its closing in the spring of 2020, I would amble towards Xi’an Famous Foods on 101st Street, taking my plastic container of noodles up to the park between Broadway and West End on 106th to sit by the statue of Ida Straus. She and her husband, Isidor, died on the deck of the Titanic, folded in each others’ arms. Before their deaths, the couple had bought a house on 105th and Broadway, right where the avenue bends uptown. Now, the water pours from beneath Ida’s bronze dress as she leans on one arm and looks toward her would-be home. In the days of Xi’an Famous Foods, a man with a bag of Wonder Bread often came to perch beside her and throw crumbs—sometimes whole slices— to the birds.

The week before I left New York that spring, a man visited Ida to plant tulips in the shape of a heart. I came to the park with a sandwich from the deli and a book I was reading for class. It wasn’t the last, or even tenth to last, time I would head to the park for a meal. But that day, despite lingering homesickness, I was the happiest I had been since before high school. The man with the Wonder Bread scattered his crumbs with a vengeance as I gathered my things and made my way back uptown. Ida watched me when I left, the tulips beneath her still unopened in their little ring. —Willa Neubauer

Reunion Courtyard A gray space.

Reunion Courtyard is the name of the plaza located between the Vagelos Alumnae Center and Barnard Hall. The courtyard used to have a bench overlooking Claremont Avenue where I sat my freshman year, when I lived nearby, in Brooks. Sometimes, I would kneel on the bench, rest my hands on the parapet, lean forward, and look as far left as possible. The wind, rushing in from the Hudson, would cool my cheeks. Then I would swing my head north, toward my future sophomore dorm and Riverside Church. A classmate I met my first semester told me Bob Dylan met his girlfriend, Suze Rotolo, the one clutching his arm on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan,” there.

When I began to write this, I realized I didn’t know the plaza’s official name. The official map on Barnard’s website leaves a gray space between the Alumnae Center and Barnard Hall, as if nothing is there. The other day, I took some time between classes to visit the courtyard. To my surprise, a white tent occupied the space. The bench was no longer. Instead, a small sign hanging from the rafters welcomed me to the Barnard Center for Toddler Research. I padded onto the blue rubber gym flooring, presumably installed for the children’s safety, and continued my search for a name. In the six-inch space between the tent and Barnard Hall, I found a plaque affixed to the building’s 104-yearold façade. To read it, I had to take a photograph, so I hoisted myself over a concrete block, which functioned as a weight for the tent, and stuck my arm out for the best angle. The inscription read: “In grateful recognition of the many ways alumnae giving strengthens the College and advances Barnard’s mission, this plaza was dedicated in 1993 and named Reunion Courtyard.” In the gray space that is Reunion Courtyard, I was at once 22, 18, an alumna, a toddler.

—Sophie Poole