7 minute read

Eyelid lesions: part four

by TheAOP

Introduction

The previous articles in this fourpart series highlighted that although benign lesions comprise the majority of eyelid abnormalities, it is important for optometrists, dispensing opticians and contact lens opticians to be alert to the hallmarks of malignancy during their interactions with patients.

Advertisement

Key points to consider in the history include:

• Personal or family history of skin cancer

• Solid organ transplantation

• Immunosuppression

• Chronicity and evolution of the lesion.

Practitioners should be alert to the following signs which raise the suspicion of malignancy:

• Bleeding

• Pearly appearance or irregular borders

• Non-uniform pigmentation

• Presence of overlying telangiectasia

• Disruption of normal eyelid appearance.

Practitioners should also be mindful that malignant lesions may not always abide by specific rules and can present with unique characteristics.

Continuing from part three, this final article in the series will present further cases of eyelid malignancies.

Sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC)

The most common eyelid malignancy in the Western world is basal cell carcinoma (BCC), accounting for 80–95% of eyelid malignancies.1 Other malignant tumours are much rarer typically involve the upper eyelid and are one of the commonest eyelid malignancies in Asia. Always consider this as a differential diagnosis for BCC or SCC of the upper eyelid as it commonly masquerades as either. It may also be misdiagnosed as unilateral blepharitis or chalazion. It characteristically erodes the tarsus and is fatal via metastatic spread and high recurrence. Suspicious lesions must be completely excised and staged in comparison and include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (<5%), sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) (1-3%) and malignant melanomas (1%). The literature shows that in contrast to the West, SGC constitutes approximately 70% of eyelid tumours in Asian countries.2,3

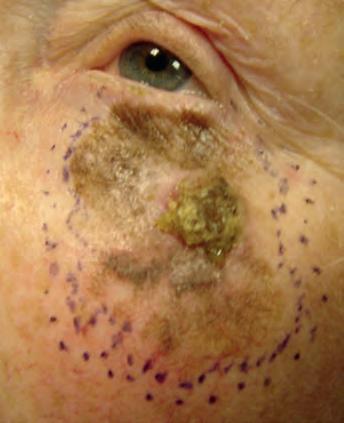

Periocular SGC arises from the sebaceous glands that line the eyelid margins (see Figure 1). Most commonly they occur in older individuals of Asian descent, and it is believed that over half the malignant eyelid tumours investigated in India are SGCs. The presence of SGC in a young patient or a family history of malignancies should raise the possibility of the condition, hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch syndrome. Muir-Torre syndrome is an autosomal dominant phenotypic variant of Lynch syndrome where a greater risk of sebaceous neoplasms and internal malignancy exists.4 MSH2, MLH1 and MSH6 are tumour suppressor genes responsible for DNA mismatch repair that are mutated in the condition. Although the disease is usually inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, sporadic cases have been reported in patients undergoing renal transplants and taking immunosuppressing medications.5 Such patients require increased surveillance for malignancy and familial genetic testing.

Sebaceous carcinomas can be difficult to differentiate from a chalazion, which can delay diagnosis of this potentially lethal malignant lesion. Like a chalazion, SGC commonly arises in the upper eyelid due to the greater number of sebaceous glands in this region. The sebaceous content is lipid-dense and can appear yellow. SGC should be suspected in a young patient of south-east Asian origin, or if a nodule precedes the onset of a chalazion with progressive effacement of the gland orifices, destruction of cilia follicles and lash loss. It should also be considered if there is a

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW C-105981

LEARNING OUTCOMES

Practitioners will be able to identify the key questions that need to be considered in cases of eyelid abnormalities relative to their scope of practice paucity of discharge or where imaging reveals a large solid component to the lesion. A pagetoid tumour is poorly differentiated, has a higher chance of metastasising and can extend into the epidermis from the tarsal plate. Intraepidermal malignant cells can result in marked conjunctival inflammation and injection; this can mimic chronic blepharitis or superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis. Be wary of seemingly benign lesions that do not respond adequately to treatment and importantly, always consider SGC where unilateral blepharitis appears to be present. A biopsy of suspicious lesions is always required, and for SGC, this is usually full-thickness rather than a superficial shave, in order to sample the posterior lamella. Sebaceous carcinoma has multiple histopathological patterns with the lobular type being the commonest. Although basophilic pleomorphic cells with vacuolated cytoplasm, prominent nucleoli and mitotic structures are classically observed in sebaceous carcinoma, these non- specific features may also be observed in BCC and SCC. Considering this, immunohistochemistry has proved helpful in confirming the diagnosis as adipophilin and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) can distinguish it from other eyelid malignancies. Patients often require staging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Management requires surgical excision with margin-controlled, ideally with rushed-paraffin sections, rather than rapid frozen sections. Where intra-epithelial conjunctival spread is suspected, then conjunctival map biopsies are also performed to exclude pagetoid conjunctival involvement. If present, this is usually treated with adjunctive topical mitomycin-C drops. Prognosis is generally good although there is up to a 25% rate of recurrence, which is far greater than most eyelid malignancies.6-8 Some individuals may require orbital exenteration if orbital involvement is present.

Practitioners will consolidate their knowledge on the key features of eyelid lesions and their management.

Malignant melanoma

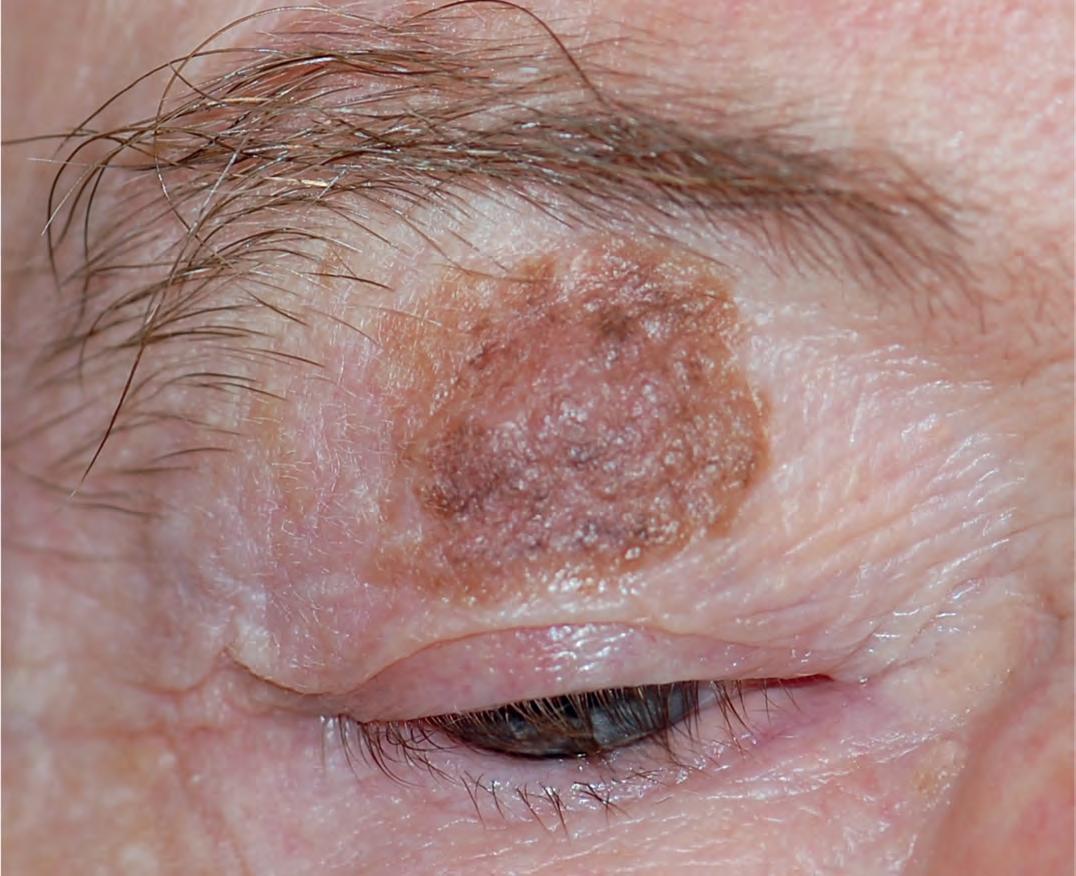

Eyelid melanoma accounts for only 1-2% of malignant neoplasms in the area.9 Like cutaneous melanoma of other bodily sites, these melanocytic tumours can behave aggressively, harbouring the potential to metastasise both locally, to adnexal and orbital structures, and distally, via haematogenous and lymphatic spread to the liver, lung, bone and brain. Rarely, systemic conditions such as familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndromes, familial melanoma and xeroderma pigmentosum predispose individuals to eyelid melanoma.10 Fair skin, a history of childhood sunburns and ultraviolet (UV) radiation are more frequent risk factors. There may also be an increased lifetime risk for males. A dermatological history of non-melanoma skin cancer and dysplastic naevus also increases risk. In more than half of advanced cases, certain mutations are found which activate downstream mechanisms culminating in increased cellular proliferation. There are numerous clinicopathological forms of eyelid melanoma but perhaps the most relevant subtypes are lentigo maligna melanoma, nodular and superficial spreading. Lentigo maligna is a premalignant lesion that exists on the spectrum of melanoma disorders and describes a melanoma in situ, akin to Bowen’s disease of SCC.11 It was traditionally known as Hutchinson’s melanotic freckle.12 Once again, the major risk factors are advancing age and chronic sun damage. Lentigo maligna is characterised by aberrations in its borders and pigmentation.13,14 Often it presents as a slow-growing macule on the lower eyelid.15,16 Histopathologically, there is uncontrolled proliferation of melanocytes within the epidermis causing hyperplasia and dysplasia portrayed by nuclear pleomorphisms and changes in nuclear size and shape.12 There is insufficient guidance on the management of this condition in the periorbital region, but recommendations suggest excision and ongoing monitoring to mitigate the risk of malignant transformation. This precancerous lesion should not be confused with lentigo maligna melanoma, which refers to melanoma that has breached the basement membrane (see Figure 2). It is the most prevalent subtype of melanoma arising in the eyelid (but least common overall) and the terminus of up to 50% of precancerous lentigo maligna.12 Nodularity arising within lentigo maligna is highly suspicious of malignancy; however, its absence does not exclude malignancy and large melanomas in situ are also alarming features of underlying malignancy.9 Furthermore, the pigmentation may extend over the eyelid margin and involve the conjunctiva, known as primary acquired melanosis (PAM) with atypia. Lentigo maligna melanoma mandates surgical excision following histological diagnostic confirmation.

Fewer than 10% of eyelid melanomas are of nodular subtype,12 which makes diagnosis and treatment more challenging as eye care specialists are less familiar with their presentation, particularly as they can be amelanotic. Conversely, the nodule may appear blue or black which should always raise suspicion. Once again, nodularity represents the vertical invasive growth phase, which is a presenting feature of this subtype. Hence, they have likely invaded deep into the dermal layer at the time of diagnosis and confer a dismal prognosis.

Superficial spreading melanoma is the commonest type overall but an incredibly rare diagnosis for an eyelid lesion. Histology shows clusters of epithelioid cells scattered throughout the epidermis and they exhibit vertical growth less frequently than the nodular type. Clinicians should be wary of patients presenting with plaques with irregular borders and varied pigmentation (see Figure 3).

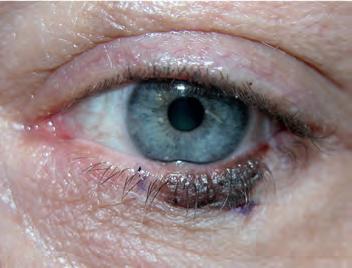

If concerned, clinicians must arrange for histological assessment of a punch-trephine or incisional biopsy sample. A superficial shave biopsy has no role where melanoma is suspected; this is because calculation of the Breslow score, a measure of the depth of the lesion, is one of the most influential prognostic markers of this disease. In addition, reflectance confocal microscopy, impedance spectroscopy and digital microscopy (dermoscopy) have shown promise in increasing diagnostic certainty. Dermoscopy is now well-established as an important tool in assessing melanocytic lesions. Figure 4 (see page 68) shows a sequence of images from presentation through to biopsy, complete excision, reconstruction and skin graft.

Margin-controlled excision with rushed-paraffin sections and not rapid frozen-sections forms excision and confirming clear margins. Middle: reconstruction of posterior lamellae and orbicularis oculi. Bottom: one month following skin graft the cornerstone of management with consideration for sentinel lymph node biopsy if necessary. Freitag et al recently stated that approximately 20% of eyelid melanomas invade local lymph nodes and immunohistochemistry staining against melanoma antigens S100, Melan A and HMB45 in lymph node biopsies can aid in detection.17,18 Alkylating chemotherapeutics have long been used first line for the medical management of melanoma and include drugs such as dacarbazine. More recently, biological checkpoint inhibitors and MEK inhibitors have been used in cases of eyelid melanoma.19,20 Prognostication is determined by subtype, the involvement of the eyelid margin, depth of invasion (Breslow score) and presence of ulceration.11 Local and distant invasions are also likely to be relevant to prognosis. Local recurrence is most likely to occur within five years of surgery and patients should be monitored throughout this period. In 2021, the largest analysis of cutaneous melanoma of the eyelid showed the five-year overall survival rate was 88.6% for melanoma in situ and 77.1% for invasive melanoma. However, older cases were included in this analysis from an era of poor melanoma prognosis. The study also found that age ≥75 years at diagnosis, T4 staging, lymph node involvement, and the nodular melanoma histologic subtype are harbingers of poor survival.21 The authors have recently published their series of 22 eyelid melanoma cases using margincontrolled excision. They observed a 36% recurrence rate within 24 months and a survival rate of 90% with minimum five-year follow-up.22

Conclusion

The final instalment in this four-part series on eyelid lesions reinforces the need for practitioners to be ever watchful for signs and symptoms that differentiate malignancies from seemingly benign cases in order to offer timely intervention and maximise the prognosis for patients.

To read this article online, access the references and take the exam, visit: www.optometry.co.uk/cpd

20 Individually Wrapped Pre-Moistened Towelettes

EDITED BY KIMBERLEY YOUNG

“MY