10 minute read

Eyelid lesions: part three

by TheAOP

The third article in this four-part series on eyelid lesions will highlight the key features of malignancies that may present in practice along with their treatment.

structures by progression of the lesion may result in diplopia and proptosis.

Advertisement

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC)

Introduction

As demonstrated in parts one and two in this series of four articles, most eyelid lesions are benign. Articles three and four in the series will explore a range of malignant eyelid lesions, highlighting the key features in these cases.

In the Western world, the most common eyelid malignancy is basal cell carcinoma (BCC), accounting for 80–95% of eyelid malignancies.1 The remaining malignant tumours are much rarer in comparison and include squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) (<5%), sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) (13%) and malignant melanomas (1%). This is in contrast to the literature arising from Asian countries where SGC constitutes approximately 70% of eyelid tumours.2,3 Early recognition of potentially malignant lesions allows prompt assessment and management, thus improving outcomes. Malignant eyelid lesions can be both sightthreatening, leading to orbital invasion and exenteration, and life-threatening through distant metastases, emphasising the need for optometrists, dispensing opticians and contact lens opticians to be alert to these presentations during their interactions with patients.

History and examination

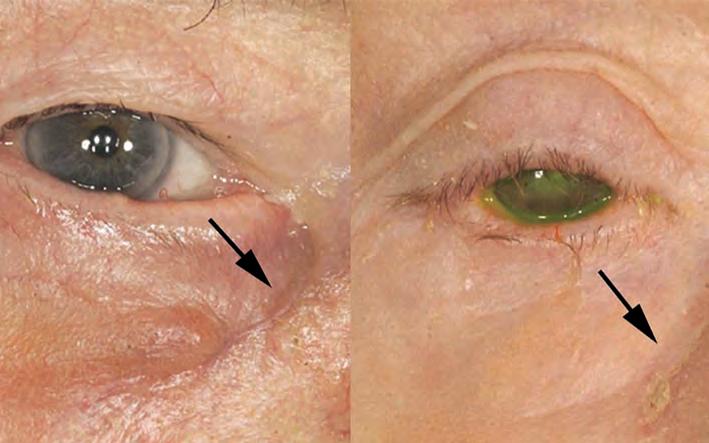

As highlighted earlier in the series, taking a thorough history is an essential starting point when assessing eyelid abnormalities. Practitioners should explore the potential for predisposing risk factors such as a personal or family history of skin cancer, solid organ transplantation, immunosuppression and exposure to carcinogenic environmental elements such as ultraviolet (UV) light and radiation. It is prudent to note the chronicity initially thought to be a chalazion and exhibited no rapid changes. However, it was unresponsive to treatment. On examination, there is central ulceration with lash loss. It required biopsy for diagnosis of symptoms and how the lesion has evolved. Rapid progression in size or colour should prompt further workup. Eliciting a precipitating event such as local eye trauma or infection may support a benign cause. A history of prior failed treatments also helps to identify atypical or malignant lesions. While malignant eyelid lesions may not always abide by specific rules, there are characteristic features that should be assessed and escalated accordingly. For instance, ulceration is the result of the disorganised proliferation of malignant cells causing them to outgrow their arterial supply and become ischaemic.4 It is seldom seen in benign lesions but is a hallmark feature of both non-melanoma and melanoma malignancy. The presence of telangiectasia overlying nodular, or irregular skin lesions should arouse suspicion, as should erosion or destruction of the normal anatomy of the eyelid, which are classic features of BCC or SCC. Delay in diagnosis of aggressive subtypes can lead to significant advancement, radical resection, and poorer cosmetic outcomes, while invasion of orbital

BCC is the most common periocular malignancy, accounting for ~90% of malignant neoplasms in the periocular region and 20% of overall BCCs.5,6 The typical patient is a fair-skinned older individual. A key risk factor for the development of BCC is intermittent intense UV radiation, as well as a history of childhood sunburn. It is understood that shorter-wavelength UVB radiation plays a greater role in the pathogenesis of BCC than longer-wavelength UVA by causing deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA) damage, disabling its repair system, and causing immunomodulation such that there is progressive acquirement of carcinogenic genetic alterations.7 For example, greater than 50% of BCC lesions show a mutation in the TP53 tumour suppressor genes. Specifically, such mutations activate hedgehog intracellular signalling pathway genes such as patched Ptch-1 which promote eyelid BCC. Arising from the abnormal proliferation of basaloid epithelial cells, they are characterised by peripheral palisading cells and random central organisation.

BCCs occur most frequently on the lower eyelid (50%) followed by the medial canthus (30%), upper eyelid (15%) and lateral canthus (5%).4 Medial or lateral canthal BCC are more likely to invade the orbit due to incomplete excision of the deep component. Extra care should be taken with the management of BCC in this area. There are over 26 different subtypes of BCC described in the literature, but the more common, distinctive, clinicopathologic types include: nodular, micronodular, superficial, infiltrative, morpheaform (infiltrative with sclerosis) and basosquamous.8 A BCC often has components of more than one subtype. Ulceration may be present in larger lesions and occurs as a result of the central core outgrowing its blood supply as the tumour grows outwards. The superficial subtype has multiple, small buds of basaloid cells descending from the epidermis with no dermal invasion. These are often difficult to surgically excise completely. The micronodular subtype has histologic features similar to those of the nodular subtype, except that it is composed of multiple small nodules, and therefore, a high risk for local recurrence. The sclerosing (morpheaform) subtype is composed of basaloid cells that invade the dermis, surrounded by dense fibrous stroma; they invade and infiltrate deeply. BCC may also be pigmented due to the presence of melanocytes and melanin, and can, therefore, mimic melanoma. Another variant is the basosquamous BCC which shows features of both BCC and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

Nodular BCC

The nodular subtype is by far the most common and accounts for over 70% of cases. It preferentially affects the lower eyelid, followed by the medial canthus, upper eyelid (see Figure 1) and lateral canthus. It appears as a raised pearly nodule with associated telangiectasia and ulceration. In general, nodulartype BCCs are slow growing and rarely metastasize. In 10% of cases, infiltrative or morpheaform type BCC occur in many forms.4 They are usually raised, firm, indurated, flesh-coloured with indistinct edges, which can often resemble cicatrisation (see Figure 2).9 Morpheaform-type BCCs tend to be more locally aggressive. Factors that may suggest its presence include large size, recurrence and associated inflammation. Other aggressive features include perineural invasion and increased immunohistochemical expression of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation.

Orbital invasion is an extremely rare complication of BCC occurring in fewer than 5% of cases, particularly those that are locally aggressive histological subtypes, recurrent, or involving the medial canthus.10,11 Signs of this include restrictive strabismus, globe displacement or destruction, or the presence of a fixed orbital mass. Computerised tomography (CT) is useful in delineating bone involvement, whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) better visualises soft tissue orbital involvement. Invasion beyond the level of the orbital septum renders local excision difficult.

High-frequency ultrasound (HFUS) is a promising novel imaging technique that permits invivovisualisation of skin lesions, allowing the determination of size, shape and volume. Exvivousage may also be beneficial to surgeons

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW C-105979 LEARNING OUTCOMES

Practitioners will be able to identify the key questions that need to be considered in cases of eyelid abnormalities relative to their scope of practice by allowing them to confidently resect skin tumours with adequate margins. Invivoreflectance confocal microscopy has also shown promise in the investigation of eyelid lesions by reducing unnecessary biopsies with 100% sensitivity and 70% specificity for tumours in the region.12 However, at present, eyelid BCC is best managed by margin-controlled excision, whereby, the repair is only embarked upon following histological confirmation of clearance.

Practitioners will consolidate their knowledge on the key features of eyelid lesions and their management.

Owing to their incredibly visible nature, periocular malignancies require careful surgical planning to ensure good oncological control, cosmesis and minimal functional disruption to neighbouring structures. Generally, enfacehistological margin examination rather than bread-loafing histological assessment allows greater assessment of the outer surface of the excision specimen. Margincontrolled excision and repair remains the most important principle to reduce recurrence. UK National Multidisciplinary Guidelines recommend that non-infiltrative BCCs less than 2cm in size, outside the eyelid region be removed with margins of 4 to 5mm.13 Smaller margins are considered in cases where reconstruction may prove difficult. A large multicentre review found that at margins of 2mm, the complete excision rate of periocular BCCs was just 83.7%.14 Furthermore, there is a significantly high rate of recurrence with wide local excision (WLE) and immediate repair for BCC; this is likely due to incomplete excision and sampling errors introduced by the bread-loafing technique commonly used to assess margins in WLE.7

Mohs excision is a labour-intensive process that results in the highest cure rate with maximum preservation of tissue. Using the same principles as enfacemargin analysis, either frozen-section controlled excision or excision with rush-paraffin sections and delayed repair achieve the same outcomes. Given that reconstruction of eyelid defects is often complex and further excision thus compromises reconstructive options and outcomes, margin-controlled excision is far more preferable to the traditional methods of WLE and immediate repair for BCC of the eyelid region.

When there is orbital infiltration, it may be difficult to obtain orientation of specimens from soft tissue, making Mohs or other types of frozen-section excision inappropriate. Often, these patients require focal orbitectomy surgery (localised removal of the involved orbital tumour). If extensive tumour involvement exists, orbital exenteration surgery (removal of the entire globe and orbital contents) may be necessary, with or without adjuvant radiotherapy.

Many other adjuvant therapies exist which are typically used in the context of inoperable tumours. For instance, Vismodegib is a hedgehog pathway inhibitor that can halt the growth of extensive, large periocular BCC where surgical excision may not be possible. It is generally well tolerated and administered orally.15 It is expensive and side effects may include alopecia, muscle spasms, diarrhoea and constitutional symptoms. For less advanced superficial BCC, 5% imiquimod, a modulator of the immune system which induces apoptosis of tumour cells, is often used for BCC away from the eyelid margin. A clinical trial demonstrated 90% efficacy in managing BCC where surgery is inappropriate.16

Linear BCC

Linear BCC describes a particular appearance of BCC that presents as a straight lesion with a 3:1 lengthwidth ratio.17 It affects the lower eyelid most commonly and runs along the tear trough groove with significant subclinical extension (see Figure 3). Sometimes these may have a nodular component but usually they are indurated. Although they appear innocuous, they display aggressive tumour behaviour and similarly require margin-controlled excision.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

SCC is the second most common eyelid malignancy, after BCC. Although occurring far less frequently than BCC, recent decades have seen an increasing incidence rate of approximately 2% per annum;18 this is thought to be due to an ageing population, who experience the consequences of cumulative exposure to environmental agents such as UV light, and less so, arsenic and hydrocarbons. Additionally, human papillomavirus (HPV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) appear to be independent risk factors for SCC.19 There is also a well-established relationship between solid organ transplantation and SCC development, particularly among those receiving lung and heart transplants in which the SCC incidence is reportedly 30% and 26% respectively.20 This finding is most likely due to the immunosuppressive medications used in the post-transplant period which impair the ability of the immune system to halt carcinogenesis. In fact, any form of long-term immunosuppression medication increases the risk of developing SCC. There also appears to be a sex predilection, with males twice as likely to develop eyelid lesions than females.18 Other intrinsic risk factors for SCC include albinism due to the lack of melanin that otherwise provides a barrier to UV light, and xeroderma pigmentosa, most likely due to the build-up of unrepaired DNA damage.

In comparison to BCC, SCC is a cancer of the cutaneous squamous cells which form the superficial epidermis.20 It is often described as the endpoint of a spectrum of disorders including actinic keratosis (AK), Bowen’s disease and keratoacanthomas. AK is a precancerous lesion arising in areas of sun exposure. Bowen’s disease, otherwise known as carcinoma insitu, describes fullthickness epithelial dysplasia that can significantly spread laterally but also deep into pilosebaceous units despite not technically invading the dermis.21 Therefore, their deep extension may be within the depth of dermis while not having invaded the dermis itself. Such lesions have atypical architecture but do not show evidence of local or regional spread. Macroscopically, it appears as a pigmented or erythematous macule and can be mistaken for inflammatory lesions like psoriasis or eczema. Its development is strongly associated with the presence of HPV subtype 16. Keratoacanthoma has most recently been described as a welldifferentiated SCC. It is a hyperkeratotic lesion which may have neutrophil infiltration. Often, the base of the lesion is well-demarcated from the adjacent dermis by inflammation on histology. It classically appears dome-shaped with central keratosis and ulceration. Ulceration is a key feature that should cause one to question its benign nature. A biopsy is required for the differentiation of keratoacanthoma and SCC. Many ophthalmologists will choose to monitor small keratoacanthomas in a bid to circumvent the need for surgery and the resultant negative sequelae.

Finally, SCC, a malignant lesion extending into the dermis with differentiation ranging from mild, moderate to poor, lacks any typical macroscopic pathognomonic features to differentiate it from precursor lesions (see Figure 4). SCC may also appear similarly to BCC, predominantly affecting the lower eyelid in 60% of cases.19 Commonly, it presents as a painless scaly, nodular lesion with irregular borders. Its irregularity and painlessness should lead one to query malignancy. More insidious lesions may present as madarosis (loss of lashes) or distortion of eyelid architecture. Histologically, the malignant cells are large and show prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm with a high nuclear-tocytoplasmic ratio. Keratin pearls are concentric rings of squamous epithelial cells that show progressive keratinisation; these are commonly found in well-differentiated squamous neoplasms and sometimes observed also in SCC, and BCC. Assessment should include a full ophthalmic examination and palpation of regional lymph nodes due to its tendency for lymphatic spread.

The primary treatment modality for confirmed SCC remains surgical excision with margin-controlled excision. Patient education on avoiding UV exposure is the key to prevention. Where surgical complete excision is not possible, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as cetuximab, erlotinib, and gefitinib have shown promise.22,23 SCC involving the head and neck appears to have a more aggressive phenotype than other anatomical regions. Periocular SCC can lead to severe morbidity through orbital invasion as well as cerebral and sinus invasion. As with BCC, surgery can also lead to significant problems with cosmesis and function, including eyelid closure and dry eye.

Conclusion

This article highlights the hallmarks of a range of malignant eyelid lesions that may present in clinic.

Practitioners should pay particular attention to lesions that bleed, have an ulcerated or telangiectatic appearance along with those that appear to be benign but are unresponsive to treatment. In addition, disruption to normal lid architecture, loss of lashes and lesions with irregular borders should also heighten the suspicion of malignancy.

To read this article online, access the references and take the exam, visit: www.optometry.co.uk/cpd