10 minute read

Eyelid lesions: part one

by TheAOP

The first instalment in this series of four articles on eyelid lesions will focus predominantly on the clinical characteristics of benign presentations.

Raman Malhotra FRCOphth and Ingrid Bekono-Nessah BSc, BMBS

Advertisement

Introduction

The spectrum of eyelid lesions encompasses both benign and malignant tumours. Depending upon the underlying pathology, benign lesions can be classified as infective, inflammatory, traumatic, or neoplastic. Most eyelid lesions are benign. Nevertheless, their array of presentations and distribution patterns can make differentiating them from malignant lesions difficult. An appreciation of the varied appearances of benign lesions may circumvent the need for referral thus minimising patient anxiety and unnecessary investigation. The first two parts in this series of four articles on eyelid abnormalities will consider benign lesions while the latter two articles will direct attention towards malignant presentations.

History

Clinical evaluation of eyelid lesions begins by taking a thorough history (see Table 1). Epidemiologically, older patients are much more likely to develop malignancy and major risk factors should be considered; these include a personal or family history of skin cancer, solid organ transplantation, immunosuppression and exposure to carcinogenic environmental elements such as ultraviolet (UV) light and radiation.1 It is helpful to note the chronicity of symptoms and how the lesion has evolved. Rapid progression in size or colour should prompt further workup. Eliciting a precipitating event such as local eye trauma or infection may support a benign cause. A history of

1 CPD POINT prior failed treatments can also help to identify atypical or malignant lesions.

Benign

Malignant History

Onset May have distinct precipitating event, for example, trauma or infection

Patient demographic Young

Progression Usually non-progressive

Associated symptoms Painful Discharge Cellulitis

Response

Risk

Examination

Eyelashes Preserved

Lid margin Preserved

Specific signs Translucency

Insidious

Older

Progressive worsening of clinical features. In some cases, will be rapid

Painless Bleeding

Immunosuppression

Loss of eyelashes

Distortion of normal architecture such as cilia and gland orifices

Pearliness

Scarring in the absence of trauma

Ulceration

Telangiectasia

Diplopia

Proptosis

Mass Soft, well-circumscribed, mobileHard, irregular, non-tender

Tethering Non-tethered

Can be tethered to underlying structures

Colouration Uniform pigmentation if presentPigmented, multicoloured

TABLE 1 Summary of the clinical characteristics of benign and malignant lesions. Diplopia and proptosis suggest orbital invasion

50 Eyelid lesions: part one

56 Eyelid lesions: part two

60 Eyelid lesions: part three

64 Eyelid lesions: part four

Examination

While the focus of this article is on benign presentations, it is important for optometrists, dispensing opticians and contact lens opticians to be aware of the characteristics of malignant abnormalities so that these can be identified and managed accordingly. For instance, ulceration is seldom seen in benign lesions but is a hallmark feature of both non-melanoma and melanoma malignancy.2 Telangiectasia represents miniature blood vessels within the superficial dermal layer commonly seen in fair-skinned, sun-exposed, elderly individuals. Their presence overlying nodular, or irregular skin lesions is suspicious. Furthermore, erosion or destruction of the normal anatomy of the eyelid is a quintessential feature of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or sebaceous cell carcinoma (SCC). Malignancy that has invaded the orbit may cause diplopia and proptosis. Pearliness caused by the hyperproliferation of cells in the basal epidermis may also be a feature of BCC. A good understanding of the eyelid anatomy is also important as the obliteration of the lash line or gland orifices is a concerning feature. Irregularity of borders arises from the variable proliferation rates of multiple cellular populations within a lesion. Hence, scalloped margins may be indicative of malignancy and should be viewed with concern if smooth borders begin to change in this way. Also consider any irregularity of contours resulting in a firm, non-symmetrical mass. Other significant features include lack of pain and the presence of bleeding. Non-uniform pigmentation is also suggestive of melanoma.

Chalazion

A chalazion is a sterile lipogranuloma caused by a meibomian gland blockage which leads to retention and stagnation of sebaceous fluid.3 It is derived from the Greek word khalaza, which literally means a small knot.4 It may otherwise be known as a meibomian cyst or internal hordeolum. Meibomian glands are named after Heinrich Meibom (1638–1700), a German physician and professor of medicine, as well as history and poetry. Meibomian gland obstruction results in the sebaceous material within the gland expanding, causing swelling. A chalazion is initially painless but as the inflammation spreads to the surrounding tissues, secondary infection with local tenderness may develop. It may grow slowly over weeks to months and become firm but will often eventually resolve. When inflamed, with or without infection, it may burst through to the external (skin) or internal (tarsal conjunctiva) surface; this often allows it to resolve more promptly.

A number of conditions, like acne rosacea and blepharitis can predispose a person to developing chalazia, particularly in childhood and early adulthood.3,4 Other risk factors include seborrhoeic dermatitis, diabetes mellitus and pregnancy. Despite popular beliefs, the use of contact lenses or makeup have not been linked to an increased incidence of chalazia. During the COVID-19 pandemic, a phenomenon known as mask-induced chalazia emerged which researchers suggest may be caused by accelerated evaporation of the tear film promoting blepharitis and meibomian oil hardening.5,6

Given the fact that there are more meibomian glands in the upper eyelid, chalazia most commonly occur in this location and can persist for months, becoming chronic. Additionally, they may cause local skin irritation, and if sufficiently large, result in mechanical ptosis or corneal astigmatism. Because of the pressure generated by the enlarged glands on the cornea, wearing contact

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW C-105977

LEARNING OUTCOMES

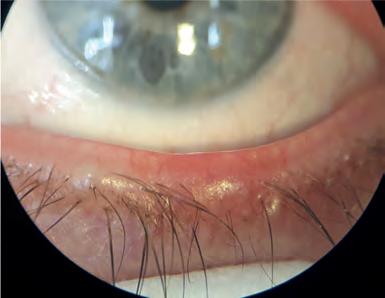

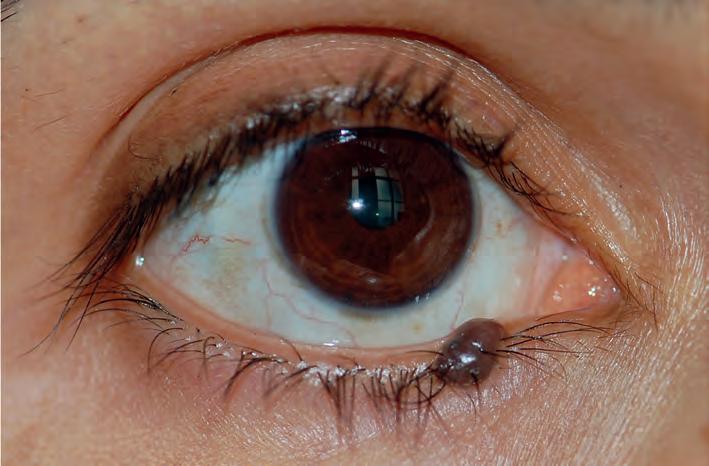

Practitioners will be able to identify the key questions that need to be considered in cases of eyelid abnormalities relative to their scope of practice lenses can also be difficult. In the lower eyelid, mechanical ectropion may occur and can cause epiphora. Chronic chalazia may develop secondary calcification, which is seen in older patients. The development of malignancy with an initial formation of a chalazion is incredibly rare. On the contrary, it is important to recognise that chalazia may mimic sebaceous carcinoma, which typically will cause some destruction or distortion of the tarsus and posterior lamella. Therefore, clinicians should ensure they evert the eyelid to scrutinise the tarsus, even in cases of lower lid chalazion as observed in Figure 1 (see page 52).

Practitioners will consolidate their knowledge on the key features of eyelid lesions and their management.

An internal hordeolum is a term used to describe an infected chalazion. The term ‘external hordeolum’ has traditionally been used to describe infections of the sebaceous oil glands (glands of Zeis), which open into the eyelash follicles. While the term ‘external hordeolum’ has also been used in the past when a chalazion becomes infected and/or inflamed and erodes through the skin, nowadays, this term is best reserved for describing infections of the glands of Zeis. Typical infective bacteria include Staphylococcus aureus or Staphylococcus epidermidis

Overwhelming superimposed infection of a chalazion can also result in preseptal cellulitis, which would necessitate systemic antibiotics.

An uncomplicated chalazion is best managed conservatively with a warm compress to reduce inflammation.7 Recently, researchers have considered the use of intralesional steroid injection.8,9 While generally safe, triamcinolone acetonide commonly depigments darker skin. The application modality also poses a risk of inadvertent globe perforation, although rare if carried out by sufficiently trained medical personnel. Another rare complication is the microembolisation of steroid particles resulting in retinal or choroidal infarction and subsequent vision loss.

For chronic chalazion, a meta-analysis identified a greater rate of cure with surgery over intralesional steroids.8,9 Surgery may also be considered for large chalazia for which the preferred treatment is transconjunctival incision and curettage. Despite resolution rates above 90%, the benefits must be balanced with the risks of infection, bleeding, as well as the likelihood of further surgical revisions, lash loss or the development of subsequent pyogenic granulomas.

Pyogenic granuloma

The pyogenic granuloma is another acquired inflammatory lesion characterised by lobular capillary proliferation.3 It is typically observed on the skin and mucosal surfaces following tissue damage such as surgery. Macroscopically it appears as an erythematous, vascularised lesion that is well-circumscribed and often lobular in shape. Tarsal conjunctival pyogenic granuloma can occur secondary to a chalazion and can also appear rapidly following chalazion surgery.10 By everting the eyelid, it may be better observed, or otherwise noticeable if sufficiently large and protruding past the lid margin (see Figure 2). Notably, it contains friable vessels which are prone to painless bleeding. Patients may occasionally complain of a mild foreign body sensation. Pyogenic granuloma can mimic squamous papilloma which also tends to bleed, or malignant lesions, such as SCC or amelanotic melanoma, in which case a detailed history should be taken to elicit the traumatic precipitant. Once again, treatment is largely conservative, with small lesions often spontaneously resolving. Many pyogenic granulomas can be managed with topical steroids, which are initiated at a high daily frequency and tapered down over weeks. Topical beta-blockers have also proven effective in inducing regression. Patients treated with timolol have shown significant reduction in intraocular pressure during treatment, but this normalises upon drop cessation.11 In the few instances where conservative management fails to induce regression, surgical excision may be considered.

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum (MC) is an infective lesion caused by direct contact with the pox virus mostly seen in children of pre-school age.12 In adults, cases are often seen in patients severely immunocompromised by acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Otherwise, there is no racial, geographic or sex predilection. Patients present with pale, waxy papules with a characteristic central umbilication (see Figure 3). Secondary follicular conjunctivitis can occur as virions are shed into the tear film but soon resolves after the lesions heal. Sometimes in chronic cases, the central umbilication can begin to ulcerate resembling a BCC and this should be actively excluded in more atypical cases arising in immunocompromised adult populations. Again, MC notably appears in multiples, in contrast to BCC which is usually a single lesion. It is also important to remember that BCC does not cause follicular conjunctivitis. Diagnostic uncertainty should prompt a biopsy for histological confirmation; this will reveal a central cavity filled with sloughed-off epithelial cells that contain molluscum inclusion bodies within the cytoplasm. The infection can usually be contained by the local immune response though active management may involve surgical excision, curettage, or cryotherapy. Lastly, previous infection does not confer lifelong immunity and so patients should continue to adhere to careful hygiene principles around those with active disease.

Acquired melanocytic naevus

Melanocytic naevi are benign tumours affecting up to 60% of adults and increasing in incidence with sun exposure.13 A naevus cell is an incompletely differentiated melanocyte. Naevus cells differ from mature melanocytes in the fact they are located around the dermo-epidermoid junction, arranged in clusters and lack dendrites. They are the primary component of cutaneous melanocytic naevi. Usually, acquired naevi become clinically apparent during adolescence as they become pigmented. They then evolve and progressively lose pigmentation thereafter (see Table 2). By age 70, the majority have become amelanotic and migrated into the dermal layer.13 The histological location determines their potential for malignant transformation and clinical appearance although there is significant overlap in macroscopic appearance. In addition, the differential for a benign pigmented lesion is vast.

Albeit rare, melanoma should always be considered in patients presenting after the second decade of life with a new pigmented lesion. Most malignant melanomas arise de novo, although up to 30% develop from pre-existing naevi, and therefore, careful assessment of these lesions is imperative.14,15

The ABCDE approach has long been described to afford early detection of possible malignant melanoma (see Table 3, page 54). Designed for ease of assessment, the parameters included in the mnemonic are asymmetry, borders, colour, diameter and evolution. Like in Figure 4 (see page 54), typical melanocytic naevi tend to be symmetrical and well-circumscribed. Junctional naevi tend to be flat whereas compound naevi may be raised. Their colouration will likely evolve over their lifetime; however, the colour should always be consistent throughout the lesion. It would be atypical to see a naevus greater than 6mm and even more suspicious of malignancy if it had grown to this size in a short period. The history will guide the practitioner on how the lesion has evolved. It is important that practitioners appropriately record their assessment of benign naevi so that comparisons can be made later. Other features outside of the ABCDE mnemonic are also important to elicit. For example, one should be mindful of the ‘ugly duckling sign’ – naevi that appear macroscopically different to surrounding moles. Cysts are reassuring features although their absence does not necessarily suggest malignancy. By contrast, feeder vessels are much less commonly seen with typical naevi and should herald consideration of an alternative diagnosis, as should bleeding tendency, oozing or pruritis.

A dysplastic naevus is a term recommended by the National Institute of Health, describing a naevus that behaves atypically.17 For example, it often grows larger than 5mm and can have ill-defined or irregular borders. Much like malignant melanoma, it may have varying intralesional colouration. Dysplastic naevi are thought to exist on a continuum between melanocytic naevi and multiple melanomas, and up to 18% of adults develop them. These individuals are at higher risk of developing malignant melanoma, though not necessarily through malignant transformation.18 Because they cannot reliably be distinguished

Examination

A Asymmetry: each half of the melanotic lesion is unlike the other

B Borders: the circumference of the lesion is irregular, scalloped, or ill-defined

C Colour: there is variation of colour within the lesion; this may include varying hues of brown, black, white, red or blue

D Diameter: length is greater than 6mm

E Evolution: changes in A–D over time or that isolate one lesion from the rest (‘ugly duckling’ sign)

Other Atypical location; ulceration; keratosis; discharge or bleeding from malignant melanoma, all dysplastic naevi merit histological assessment and consideration for excision.

Conclusion

Reassuringly, most eyelid lesions are benign rather than malignant; however, practitioners should be alert to the presence of suspicious signs and symptoms during eye examinations, contact lens consultations and when dispensing or adjusting spectacles. In summary, lesions that bleed spontaneously are generally abnormal. Prior to this, malignant lesions may ulcerate, or develop visible vessels known as telangiectasia. Lesions that appear to be benign, but which are resistant to treatment or persist despite normally self-resolving are also symptomatic of malignancy. Firmness and non-tenderness are concerning signs. If there is lid margin involvement, loss of normal architecture or lash loss is abnormal, as is pearliness or cicatrisation in the absence of trauma. Furthermore, malignant melanomas should be assessed using the ABCDE method, which evaluates asymmetry, irregular borders, colour variation, diameter over 6mm and evolution. Atypical or rare presentations are likely to lead to misdiagnosis, but through detailed history-taking and diligent ophthalmic examination, one should be able to identify red-flag features that warrant further investigation.

To read this article online, access the references and take the exam, visit: www.optometry.co.uk/cpd

Raman Malhotra is a consultant ophthalmic and oculoplastic surgeon at Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Trust, East Grinstead.

Ingrid Bekono-Nessah is a foundation year one doctor working within South London. She has a keen interest in anterior segment and paediatric ophthalmology.