8 minute read

History Corner

Leaving a job with a family legacy can be a big decision. Ridley Wills II talks about how he made one of the biggest choices of his life.

BY RIDLEY WILLS II

The biggest decision of my lifetime was to marry Irene Jackson. This summer we will have been happily married for 59 years.

The next biggest decision in my life came in 1983 when I was a 49-years-old senior vice president of American General Life and Accident Insurance Company with more than 1,000 home office employees reporting to me.

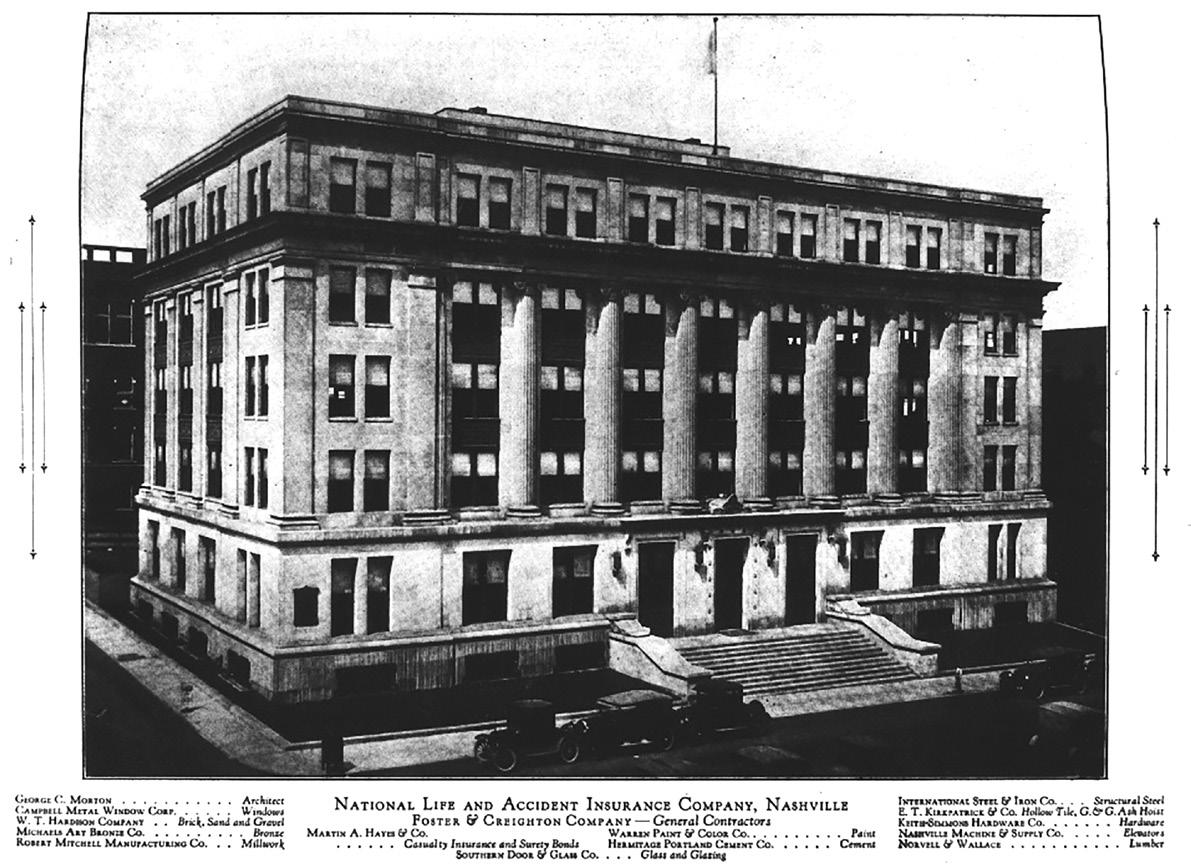

I had spent 25 years in the life insurance business, nearly all of which time I was affiliated with the National Life and Accident Insurance Company that my grandfather, Ridley Wills, co-founded with Neely Craig and Runcie Clements in 1901.

The decision facing me in 1983 was whether to remain with American General, which had acquired control in 1982 over NLT, the parent company of the National Life and Accident Insurance Company.

The safer decision was to remain with American General, where I was a senior officer with a large salary and a possible path to the presidency. The riskier choice was to resign from American General, and choose another career. I thought that if I left AG, I would probably never be on the board of Vanderbilt University, where my father, Jesse Wills, and my grandfather, Ridley Wills, both served as members.

In the late 1970s, before anyone knew that NLT would be acquired in a hostile takeover, Dr. Garth Fort, medical director of National Life, said to me, “Ridley, someday you will be president of National Life.”

In 1982, that possibility disappeared when American General acquired NLT and its subsidiaries.

I want my wife, children, grandchildren, and my brother and sister, Matt Wills and Ellen Wills Martin, to understand the thought processes that led me to resign from American General in 1983.

By the time American General announced its acquisition of NLT on November 4, 1982, I had already decided to stay with American General long enough to determine if I felt comfortable working for that company. As I was then chairing National

CONTINUED ON PAGE 6

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 5

Life’s annual United Way campaign, I did not want to leave in the midst of the campaign, because, without leadership, I thought the campaign would flounder. That year, the combined employee contribution from L&C and National Life employees to the United Way was $288,380. In the 1987-88 United Way campaign, the AG home office employees gave $172,578, a 30 percent decrease over five years. For a number of years before the takeover, National Life had raised more money for the United Way than any company in Nashville. In 1978, I had been chairman of the entire United Way campaign in Nashville.

Very quickly following the merger, two things happened that told me I probably should resign from American General. In 1982, I had been on the board of directors of National Life for several years. With the takeover, the name of the board was changed to the American General Life and Accident Insurance Company Board. One day, when the board was to meet, I got a phone call from the secretary of one of the executive officers telling me that I did not need to attend the meeting. When I asked her why, she said I was no longer on the board. I was taken aback at the insensitive manner in which AG’s executive management handled my dismissal.

One of the innovations that American General brought to the National Life office staff of over 1,000 people, was to introduce a management plan called Modelnetics that every home office employee was expected to learn. Modelnetics consisted of 50 or more models, which collectively gave the philosophy of the company.

Two of the models that I remember were, “If you are on a northbound train and want to go south, you should get off the train.”

The other was, “the appropriate amount of resources to accomplish a job is the minimum resource needed to accomplish the task.”

American General needed someone to teach the first Modelnetics class to National Life employees. To do so, that person would need to go to Sacramento, Calif., where Harold Hook, American General’s CEO, had a brother who taught the class to various American General company employees. I volunteered to be that person, was accepted, and went to Sacramento for a week to learn how to teach the class at National Life. There I also learned that Harold Hook owned Modelnetics and profited by selling it to his companies. I volunteered to teach the first class at National Life because, if I did leave the company’s employment, I thought I would like to teach Nashville history as an ad hoc professor at an educational institution. So I taught the first class at National Life.

In December, 1982, two decisions I made were overturned I suppose by H.J. Bremerman, Jr., the newly appointed CEO of American General Life and Accident Insurance Company of Tennessee. In December of each year, I evaluated the written goals of the department heads reporting to me. Four of those departments paid claims — death claims, policy loans, cash surrenders, and sick and accident claims. I gave each of these department heads a goal to pay claims as quickly as they could. The faster their employees paid claims, the larger the annual bonus I gave them. I did this because I knew that American General policyowners, many of whom were African-Americans, were relatively poor. I knew that they needed the money. I also knew that, when my grandfather, Ridley Wills, and Neely Craig founded National Life in 1901, they decided that if they were good to their policyowners who then were all Black, everyone else would do just fine. Accordingly, Neely and Ridley put a sign in the agent’s room of every district office that read as follows:

Pay all just claims promptly and pleasantly;

Reject all unjust claims firmly but pleasantly;

If there is any doubt, give the policy owner the benefit of the doubt.

Soon after giving bonuses in December 1982, I received word to quit paying claims so promptly. This was a shock and a second sign that I was on a train going north while I wanted to go south. The other blow came when I recommended salary increases for my department heads. At about the same time, the underwriting departments of Life and Casualty and National lIfe were housed side by side in what had recently been the NLT Tower but were still operating separately.

Jack Gwaltney headed the National Life Underwriting Department while Clark Hutton headed the smaller Life and Casualty Underwriting Department. Jack was making $65,000 a year while Clark, who was within a year of retirement, making $35,000 annually. I did not recommend a salary increase that year for Jack, but recommended a modest cost of living increase for Clark. My recommendation for Clark was turned down, assumingly by the CEO.

American General announced at about the beginning of 1983 that it would sell WSM, the Grand Ole Opry and the Opryland Theme Park. Soon thereafter, I was invited by Walter Robinson, the former CEO of NLT, to join a group he headed to buy these companies. I felt honored to have been asked to become a minor member of the group, which made an offer of between $200 million and $300 million for the companies to be sold.

On March 16, 1983, American General announced that it would shop around for a larger offer. On July 1, 1983, Gaylord Broadcasting signed a letter of intent to buy the Opryland properties for $270 million.

Sometime in 1983, I was asked to fly to Houston and spend a weekend with American General’s CEO, Harold Hook, Jr., on his ranch.The only reason I could think of why he would want to spend time with me was because he was trying to decide whom to name as executive vice-presidents for the Nashville company. He already had a CEO, H. J. Bremerman Jr., a vice-chairman, Philip G. Davidson, and would shortly announce that my boss at National Life, Carroll Shanks, would be president and COO. Hook wanted to name three executive vice-presidents and was considering promoting three senior vice-presidents to those positions.

In the running were Neil Anderson, National Life’s Chief Actuary; William Darragh Jr. who had recently moved to Nashville from another subsidiary company; Bob Devlin; possibly Sydney Keeble, Jr. formerly of Life and Casualty, and, I suppose, me. Devlin, whose office was next door to mine, and I were jointly responsible for merging the home office employees of Life and Casualty and National Life. I earlier realized that Devlin, who had come up from Houston, never wrote anything down, and talked daily with Harold Hook. I thought he was a spy.

By this time, sometime in 1983, I decided to quit. A couple of hours after submitting my written resignation, I saw Bremerman, the CEO, downtown at lunch time. He stopped and said something to the effect that he knew I would enjoy being in Texas with Harold Hook. I told him that I was not going to Texas and had just submitted my letter of resignation. He seemed disappointed. Bremerman was later fired by Hook.

Leaving American General was my second best decision ever. After doing so, to my surprise, I was elected to the Vanderbilt University Board of Trust when I didn’t even have a job, and chaired MBA’s Board of Trustees for nine years, hiring two headmasters, Douglas Paschal and Brad Gioia. I have since 1990 written and published 27 books and three booklets, and was given in May 2016 an honorary PhD by the University of the South for being one of Tennessee’s foremost historians. I also taught Nashville history as an ad hoc professor at Belmont University for fifteen or more years, and in the fall of 2021 will be inducted in the Southeast YMCA Hall of Fame in Black Mountain, N.C.

Ann Potter Wilson, David K. Wilson’s first wife, on hearing that I had left American General, told Pat, “I never thought Ridley was suited to be in the life insurance business.”

What I know for certain is that I have received much enjoyment and satisfaction in my life since leaving American General. I made the right decision.