11 minute read

1 History of Buffalo Gap, Texas

1 A History of Buffalo Gap, Texas

In 1876, the centennial year of the United States, a sixteen-year-old girl named Molly Hampton decided to marry. She was a native of Tarrant County, Texas, and had lived her life south of its county seat, Fort Worth. Her new husband was J.B. Clack, a Tennessean about ten years her senior. Together they plotted where they would build their lives together. “A short time after our marriage we decided to immigrate west and ‘grow up with the country,’” she wrote. “I was delighted by the prospect.” Clack already had a notion of where they were going. He had spent the winter of 1873–1874 in Taylor County hunting buffalo and had fallen in love with the country. He thought it would be an ideal place to settle and raise a family. “True, [although] I knew nothing of this part of the state except what had been told me,” Molly wrote, “I was willing to risk his judgment in selecting a location that would suit our requirements.” So, after saving their money for two years and gathering supplies including a pair of roosters—a “silkie” and a red rooster—and two hound pups, the couple loaded a wagon, left Fort Worth, and headed off to establish themselves in a new land. “It was Taylor County,” Molly wrote, “beyond ‘where the West begins’ that we were to build a home.” They would be among the first to put down roots in this new country. The Texas legislature officially established Taylor County in 1858, naming it after Alamo defenders Edward, James, and George Taylor. At the time of this founding, however, there were no permanent settlements in the county. It was still the domain of nomadic Comanche

Advertisement

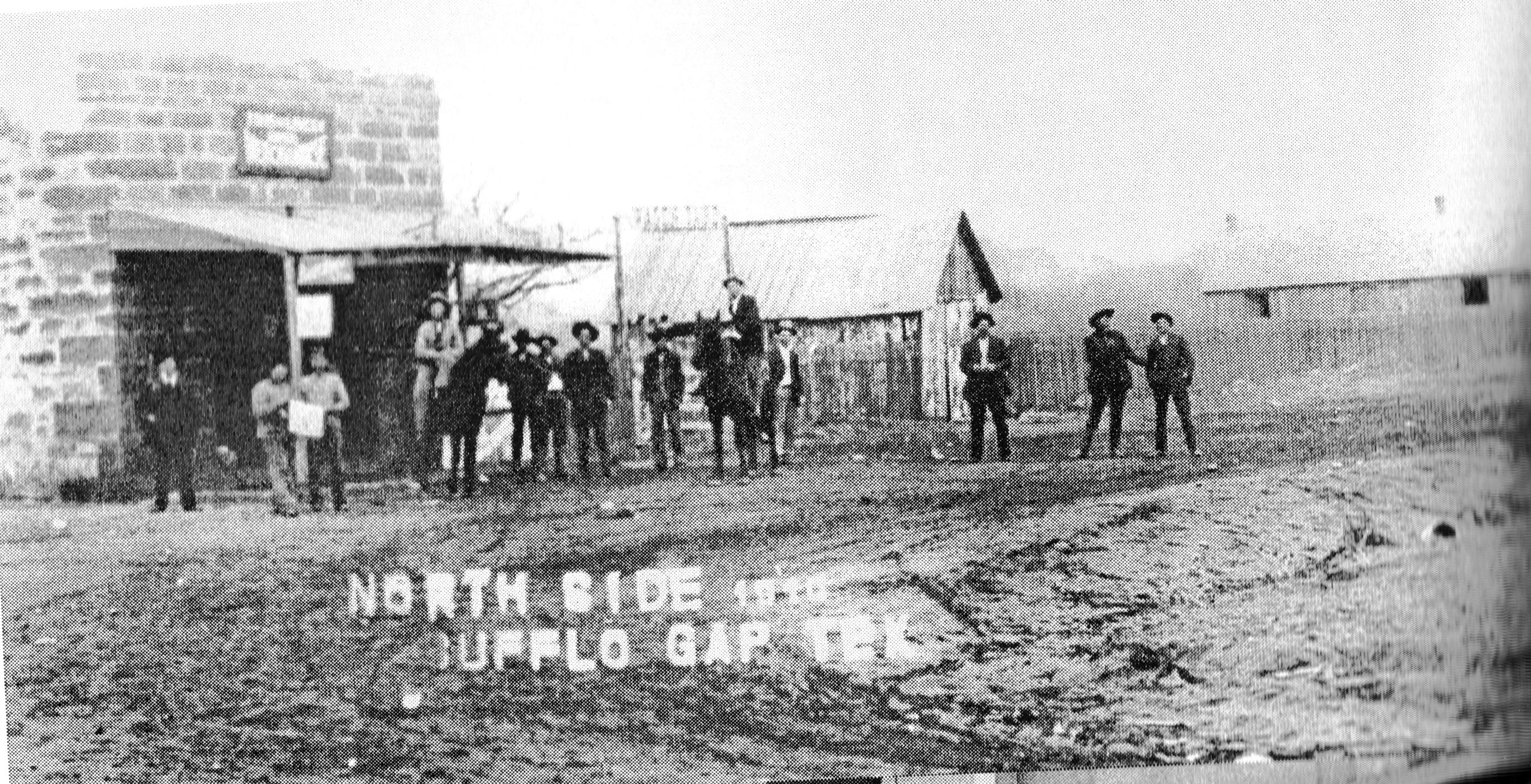

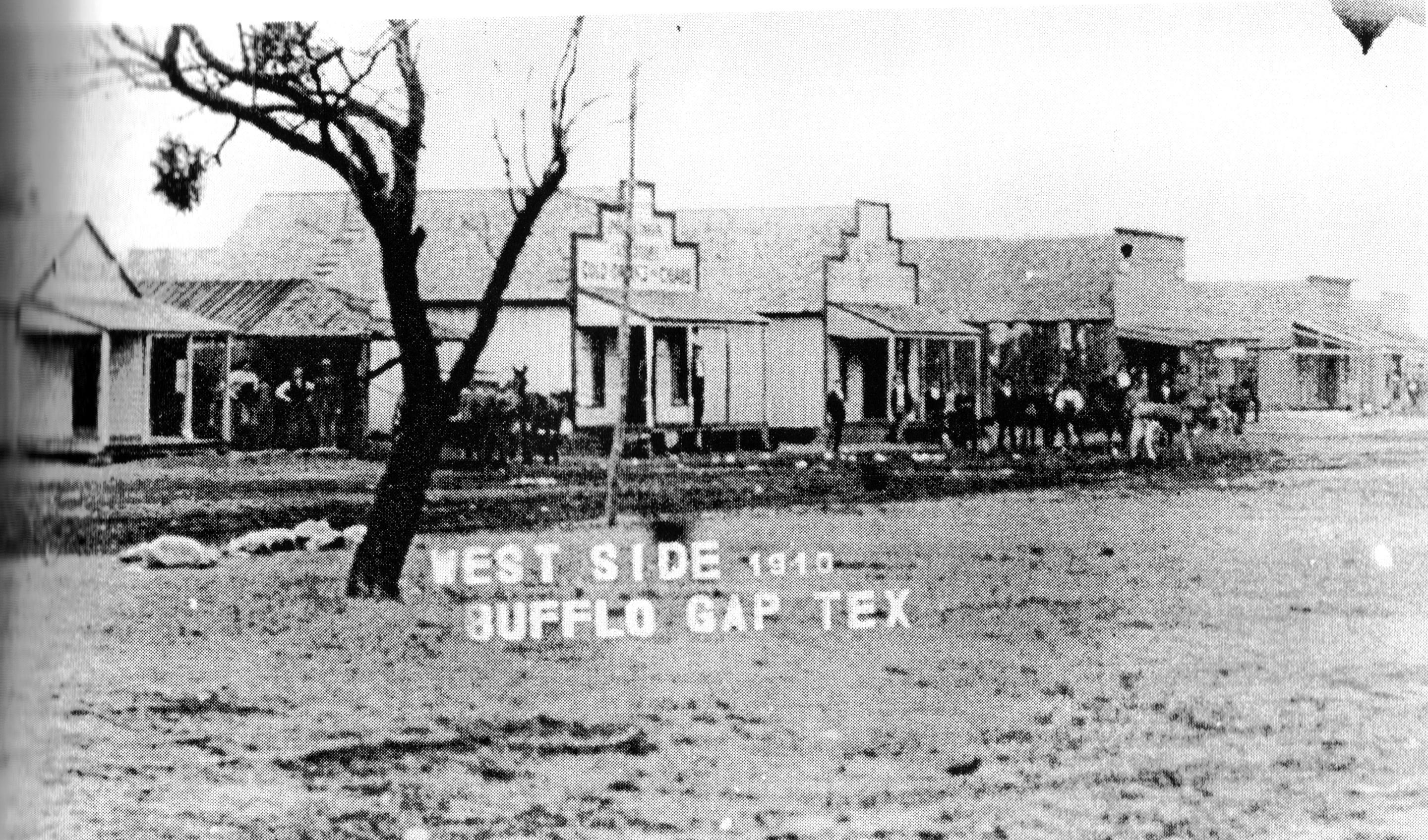

1910 Buffalo Gap, Texas Town Square

tribes and several hundred thousand roaming bison. But change, and a new wave of immigration, would be washing into the region at an accelerating pace, and within a decade the area would bear the hallmarks of a civilization. The dynamic 1870s were rife with changes that would propel settlers like the Clacks and the Eagle Colonists into the area. With the removal of the Indians to reservations in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) in mid-decade, the area opened up for buffalo hunters and adventurers to find their fortunes. The great southern herd of American bison wintered just south of the Callahan Divide, a line of hills that stretched through the center of Taylor County. Amid this sea of grass lay an oasis. The buffalo passed through the region by way of a natural gap in the Callahan Divide filled with large live oak trees and good watering opportunities courtesy of the Elm Fork of the Brazos River which cut the limestone hills at that point. When the first Anglo buffalo hunters began harvesting hides in the region, they named the pass Buffalo Gap, and over time, the name stuck. Before long, the timber-lined stream sported a semi-permanent collection of residents bolstered by scores of transients. Big game hunting gave rise to this shanty village. In 1875, buffalo hunters gathered there as a natural base camp for their hunts. The first homes in the area were little more than a collection of dugouts, skin tents, and sod houses inhabited by migrant buffalo hunters, skinners, and hide traders—not much in the way of a civilized community. By the next year, however, Buffalo Gap became a significant

“hide town,” a place were buffalo hide merchants from the East could set up shop and buy hides in bulk from the hunters. Many of these merchants built log cabins, and the resident population of Buffalo Gap in 1876 was about thirty.

Hunters skinning buffalo (Archives and Information Services Division, Texas State Library and Archives Commission).

The frontier town continued to grow and attract a wide variety of settlers. Surveyors laid out streets and town lots, and by 1877 the number of residents in Buffalo Gap had grown to one hundred, qualifying the town for a post office which residents located in a one-room frame house near the town square. Population meant business, and enterprising merchants catered to the needs of new residents and, before long, their families. Other entrepreneurs did as well:

there were at least two log cabin saloons that drew gamblers and gunmen to the region. Within a year the number of permanent residents in Buffalo Gap had quadrupled to more than four hundred, making the town a much more substantial community. Texas Gov. Richard B. Hubbard formally recognized the county and named Buffalo Gap the county seat on July 3, 1878. With this development, town residents elected a sheriff and built a temporary log cabin courthouse. Before long the town square sported growth—lumber-constructed buildings including a two-story hotel, a general merchandise store, and a blacksmith shop. The Clacks did not move to the new town but built their homestead near the remnants of an earlier settlement effort, the Eagle Colony, a few miles northeast. German immigrants working in the factories and farms of the American Midwest had banded together and moved to the region a few years before. However, graft and corruption on the part of the organizers as well as a harsh turn of weather had doomed the venture, and most had returned to Indiana and Illinois. A few clung to their cabins and fields in what would soon be the Clacks’ new neighborhood. Located along the banks of Lytle Creek, the cabins, shacks, dugouts, and shanties that made up the settlement looked to the southwest, toward Buffalo Gap. When the town gained the status of county seat, it became the center for the Clacks’ access to supplies, news, business, and legal transactions.

The designation of Buffalo Gap as the county seat generated even more growth. Taylor County officials approved the first public road through the area, which replaced the old animal, Indian, and military trails that had previously served as an informal road network. Instead of linking ancient hunting grounds and extinct forts from the past, this new road would be a pathway to the future. In 1879, construction began on the two-story limestone structure that would be Taylor County’s first courthouse, just a block off the town square. Towering over nearby homes and stores, the imposing structure was completed and open for business in 1880. Officials moved county prisoners from Coleman City to Buffalo Gap in April 1880 and housed them in the large holding cell on the second floor. Law and order had arrived on the frontier and, with it, the first signs that the community was growing up. By 1880, Taylor County had a population of 1,736, mostly concentrated around Buffalo Gap. With the courthouse, two banks, a newspaper, a jail, a dozen stores, an undertaker, a livery stable, a hotel, and five saloons, it appeared that Buffalo Gap might become the metropolis of West Texas. Area residents took special pride in their courthouse, as it represented the arrival of law and order to what had formerly been with wilds of the Texas frontier. While the new blockhouse-looking structure would do as a temporary home for county business and its lawless miscreants, citizens laid plans for a more grandiose structure—a true temple of justice—to occupy the very heart of their town

square. The building’s ornate clock tower and imposing stature would enroll Buffalo Gap into the ranks of established communities, they believed, and begin the transformation of this little hamlet into one of the heartland cities of America. Little did these civic boosters know that it would take more than bricks and mortar, plans and visions, to make a community thrive in the rapid-paced industrial age of the 1880s. In the late 1870s railroads—not creeks, timber, and roads—emerged as the determining factor in the establishment of new towns. Residents of Buffalo Gap understood the economic benefits of this technology, and they certainly aspired to be on the route of the Texas and Pacific (T&P) Railroad that slowly snaked its way westward from Fort Worth. As the T&P line neared Taylor County, several enterprising ranchers made a move to cash in on the arrival of rail service. Col. Claiborne M. Merchant of Belle Plain in Callahan County knew that his community would most likely be bypassed because of terrain and topography, and he tried to buy land in the Buffalo Gap area, knowing that the value would appreciate rapidly with the arrival of the first train. His attempts at a clever real estate move failed, however, when he discovered that other businessmen had beaten him to the prime land. Undaunted, Merchant purchased land in the flat and grassy northern part of the county, hoping to entice the railroad to build through his land, bypassing Buffalo Gap altogether and leaving its cloud of speculators in the dust.

Ultimately a coalition including Merchant, other prominent cattlemen in the area, and the railroad made a deal by which area ranchers would donate land to the T&P Railroad for a depot, siding, and cattle-loading pens in exchange for the railroad laying out a town, arranging for publicity, and staging an auction, with the proceeds being divided between the landowners and the T&P. On March 15, 1881, the company held a town lot auction for the new site at mile post 407 for a community they christened “Abilene.” In just two days, they sold more than three hundred lots. As Abilene boomed, Buffalo Gap busted. On January 2, 1883, Abilene incorporated, and with the railroad dividing the community, the new town was well suited to link itself to the growing cosmopolitan interests of the nation as a whole. In contrast, Buffalo Gap, though only a few miles from the railhead, remained comparatively isolated. By the summer of 1883, a call emerged for the movement of the Taylor County seat from Buffalo Gap to Abilene, something that undoubtedly worried Buffalo Gap residents, who saw the county seat as perhaps the only thing that kept the community going. But on October 23, 1883, Abilene won the election and the county seat moved north. Amid accusations of foul play and suspicious voting practices, citizens of the stricken community banded together in posses and mobs to protest the vote. Despite the real possibility of violence, the angry citizens eventually dispersed, but only after inflicting their vengeance on a flock of poultry owned by a county judge. Their bellies full of fried

chicken and their anger assuaged, the residents of Buffalo Gap knew their community faced an uncertain future, but they laid plans to make the best of their bad situation. Even though losing the county seat proved disappointing, many residents of Buffalo Gap remained stalwart in their devotion to the town. By 1884, the town population had fallen to six hundred, but residents still made plans to build a college—an ambitious endeavor for any frontier community. In June 1885 Buffalo Gap College, a Presbyterian school, opened its doors. Proud Buffalo Gap residents began to promote their town as the “Athens of the West.” Another development also helped Buffalo Gap to remain viable—the arrival of another railroad ten years later. In 1895 the Santa Fe Railroad was built through the town, finally connecting the community to the world. Even so, Abilene had too big of a head start and Buffalo Gap would forever be in its shadow. Buffalo Gap continued a slow decline despite it relative successes. With falling enrollments, Buffalo Gap College folded in 1902, when its charter expired. Over the course of the next two decades the town’s population fell to fewer than four hundred, with only a handful of businesses remaining in what had once been a thriving community. The town center remained a gathering place for local farmers and ranchers, but it would never compete with Abilene as a commercial hub. Undaunted by the growth of Abilene to the north, local leaders in Buf falo Gap regrouped to create an identity

for their community as a heritage, cultural, and commercial center. The first step in bringing this new identity to the town was the “Old Settlers Picnic,” a popular annual event that started in the 1920s. Building on this identity in the mid 1950s, local attorney Ernie Wilson purchased the old stone courthouse and turned it into the Ernie Wilson Museum of the Old West. This site eventually evolved into the Buffalo Gap Historic Village. Adding to this attraction, several artist galleries and stores have moved to the town, joining restaurants, gift shops, and other businesses that benefit from and enhance the town’s “old-time” charm and environment. Today, Buffalo Gap remains at the heart of Taylor County. The town has weathered many challenges and hasn’t seen a significant population shift for more than a hundred years. Even so, it remains a reminder of the turbulent days when Texas “grew up with the country.” Its successes and failures, hopes and disappointments are, in microcosm, the growing pains of an entire nation. The transformation of a frontier into the heartland of America was done by fits and starts, and the people who lived through it provided an important legacy to the citizens of today.

Buffalo Gap College

Buffalo Gap circa 1910