10 minute read

History

from Bribie Magazine 2022

by Tarn Radford

WHEN WORLD WAR II CAME TO TOORBUL POINT

From 1942-45, Toorbul Point (known nowadays as Sandstone Point) was the site of a large Allied amphibious training base. Historian Ron Donald recalls this vital era of Australia’s war history. The waters of Pumicestone Passage at Toorbul Point ripple past the bows of motor launches towing lines of boats filled with fully-armed Australian soldiers. It is August, 1942, and the training of soldiers for amphibious warfare in Papua New Guinea has just begun - for the first time ever on the coastline of Australia.

Advertisement

Within the next eight months, more than 25,000 Australian and United States soldiers will be prepared at the Toorbul Point base for amphibious attacks on Japanese-held territory on South-west Pacific islands to the north.

Sailors of the RAN and United States Navy will also take part in the amphibious training, as well as Australian commandos and “soldier sailors” destined to man supply ships in the Pacific theatre of the war.

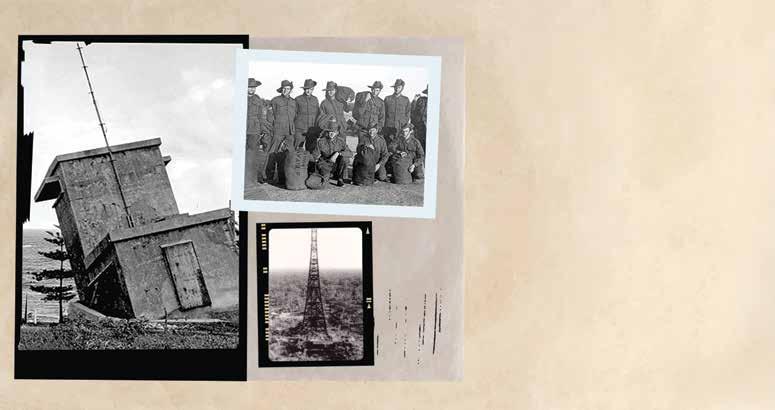

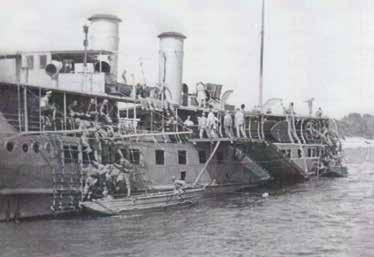

American Officers observe a beach landing from the stern of HMAS Koopa in the early days of the Toorbul Point Combined Training School. Folding boats were being used at the time to carry the soliders, with four on each side paddling the craft and an oarsman at the stern. Landings were made both day and night with tide times and currents being critical to the cast-off times in the exercises. The Combined Training School (to give it its official title) was an initiative of the Australian Army and established initially to train troops of the AIF 7th Division who had returned in early 1942 after service in the Middle East. Headquarters of the division were at Woodford and its battalions were distributed throughout the South Queensland area. The CTS was under the command of Lieut. Col. Lionel Rose, who had also served - and been wounded - in World War I at the age of only nineteen.

The CTS naval wing - known officially as RAN No. 5 Station - was the province of swashbuckling Englishman, Commander Jack Band, a RAN reservist who was destined to pay the supreme sacrifice during an Allied amphibious landing in New Guinea.

Navy directive to boat owners

The Australian Army did not have any small boats of its own for amphibious training and the British Army had its hands full in campaigns in Europe. Australia, therefore, had to find its own resources. An article in leading Queensland newspapers on Monday, June 8, 1942, carried an official directive under this general heading: All types of boats to be handed over.

The story read: “All boat owners in Queensland must hand their boats over to the military authorities. This is the result of an order by Captain E P Thomas, District Naval Officer, Queensland, who said yesterday that it would take effect at once”.

“It is estimated that there are over 2000 boats on the Brisbane River and as many more on the waterways of Queensland coastal areas.” “The order applies to skiffs, rowing boats, motor launches, trawlers, drifters, ferries, yachts, dredges, barges, canoes; in fact, craft of any description, including dumb lighters. “The owner must clearly and legibly print his name and address on the vessel and leave with it anchors, cables and mooring ropes. He must remove the engine if it does not exceed 5hp and remove from the boat all portable fittings, batteries, equipment and personal belongings”. “Boats must be placed in the water in a position accessible to officers taking over craft or must move them to another place directed”. “There are some exemptions for people using boats to earn a living such as fishing boats and vessels authorised to be used as part of the

Naval Auxiliary Patrol”. “Any owner who fails to comply with the order may have his boat removed or destroyed. Boats taken over by the Military will remain in the charge of the forces for the duration of the war. They will be taken to a ‘boat farm’ where they will be cared for.” Thus the Combined Training School at Toorbul Point had to wait for towing craft such as launches to become available. Meantime, the Army had arranged for the school to be supplied with “folding boats” - collapsible boats made of timber and canvas and used mainly as pontoons for military bridges across expanses of water. But, in the case of the CTS, the boats would be used to transport troops on amphibious day and night training raids on beaches on Bribie Island.

In the lead-up to the amphibious training, work had proceeded around the clock - electricity generators on site worked full-time - on the establishment of the CTS and its range of associated facilities and buildings. Among these was the personnel pier from which the soldiers would access the moored folding boats. The first pile for the pier was driven on July 19; it extended 330 feet out to 8ft. 6ins. at low water in the passage and was ready for use 14 days later. A mock-up ship’s side was erected on the beach to enable the soldiers to learn how to use cargo nets for descending into, and climbing up from, amphibious craft at sea. Nearby was a full-scale model of a landing craft for training in entering and leaving procedures. A water supply for up to 1500 men was developed from local bores, supplemented by tanks. In a report, Lt. Col. Rose noted: “Until such time as proper landing craft became available, good training was carried out by landing the army from folding boats, which were towed to a position off the beach to be assaulted by launches manned by the RAN. Ten launches were asked for initially and the first five arrived in August (1942). Towing six folding boats each, there were just enough launches to provide for the first battalion to be trained. “The folding boat equipment proved to be admirably suited to the task, towed well and were safe in quite heavy seas, even with 24 fully-armed and equipped men on board. Thirty boats were required initially and arrived in time. This number gradually increased to about 100…” The soldiers kneeled in the folding boats. Initially, voluntary members of the Naval Auxiliary Patrol helped to co-ordinate the launch-folding boat exercises and were gradually replaced by RAN ratings, the majority of whom had trained at HMAS Assault at Port Stephens on the NSW coast.

HMAS Koopa at anchor during an exercise in Moreton Bay with troops in folding boats. The folding boats were launched down a specially designed, oiled, timber chute on the ship’s port side and held in place by a warp (at an angle) for the boarding procedures. Army chief Lt. Gen. Sir John Lavarack inspected the CTS at Toorbul Point eight days after it opened for training and witnessed a battalion landing off South Point on Bribie Island. Each of the folding boats had two oarsmen whose job was to utilise their skills and the prevailing tide to ensure that, after being cast off from the launches, the boats came ashore at the area designated for the “attack”.

The exercises were carried out at night, as well as in daylight, and RAAF aircraft simulated battle conditions with strafing and bombing attacks nearby. RAN Admiral Sir Guy Royle was among high-ranking visitors to the school in its early days.

Arrival of US personnel

Between August 5 and September 7, 1942, four AIF battalions trained at the CTS, being followed by four US battalions (September 9 - October 22), two AIF commando companies ((October 12-30), three US battalions (October 27, 1942 - January 1943), one Australian Militia battalion and artillery regiment (January-March), and one Australian tank regiment (March 14-19). Units of one of the US divisions (41st) had to travel 380 miles each way to the school from their area of concentration near Rockhampton. The initial method of training with launches and folding boats began to change at the school with the arrival in November, 1942, of two US landing craft of the first batch to arrive in Australia. The number of craft and USN personnel gradually increased and, by the middle of February, 1943, there were sufficient craft to land an entire battalion, signalling the end of the launch-folding boat era. Shortly after, US vessels at the school included several amphibious landing craft big enough to carry five 25-tons General Grant tanks. In the meantime, the well-known Moreton Bay passenger ferry, s.s. Koopa had also been brought into service, a wharf having been built for her at the school to load soldiers for landing exercises on Bribie and Moreton Islands.

Growth in naval personnel numbers

From a modest beginning with 16 Naval Auxiliary Personnel men, RAN ratings of all descriptions were posted to the CTS and in August, 1942, naval strength increased to 80. It reached its peak in December when all ranks and ratings numbered 300, including about 18 officers. In the meantime, the school had been visited by Navy chief Sir Guy Royle. On December 8, 1942, a detachment of two officers and 40 ratings of the United States Navy arrived at the school with the objective of teaching the RAN staff the peculiarities of US landing craft. Accommodation became very taxed, especially as this detachment increased quickly in numbers and without notice. By the middle of February, 1943, there were sufficient USN craft at the school to land an entire battalion and the launches and folding boats were no longer needed. CTS assumed the new name of Amphibious Training Centre in March, 1943, under the command of US Admiral Daniel Barbey (who made a personal visit) and the fleet increased rapidly, including three 105ft. long LCTs each capable of carrying five 28-tons tanks. US naval personnel at the centre numbered about 400.

High-ranking US Army officers who witnessed training operations at Toorbul Point included Lieut-Gen R Eichelberger, 2-i-c to Supreme Allied Commander General Douglas MacArthur. Commander John Band, officer-in-charge of the naval wing (RAN Station No. 5) at the Toorbul Point combined school also tendered an official final report as his Army contemporary, Lieut.-Col. Rose, had done.

This aerial view of the early stages of construction of the Bribie Island bridge in 1961 - 16 years after the end of WW2 - shows the remains of jetties built by Australian Army personnel of 2/7 Bn. in 1942.

Cdr. Band wrote on March 15, 1943: “Our allies, the American amphibious group here, have now become a permanent detachment. They are proceeding to get plans out to build quite an elaborate show to accommodate between 400 and 500 seamen, side by side with the Australian Naval wing.” Referring to the early stages of the school and construction of the personnel jetty, Cdr. Band wrote: “Permanent mooring lines were rigged on the jetty to which were secured folding boats as used by Army engineers for bridging. They were secured so that they could be warped (at an angle) alongside two pontoons, one on either side of the jetty. “When this system was organised, a full infantry battalion of equipped troops could embark in seventeen minutes.” With Toorbul Point now under its control from March, 1943, the US Navy maintained the base for the training of crews of landing craft and also participated in some assault exercises with US troops on the eastern beach of Bribie Island.

Era of the “seamen soldiers”

With the Japanese retreating in the South-west Pacific area, the Americans moved out of the camp and, from late 1944, it was occupied by “seamen soldiers” of Australian Army Water Transport, REI, the units being the 42nd and 43rd landing craft companies of 54th Port Transport. The latter group had a complement of three officers and 140 personnel, who arrived at Toorbul Point in 20 barges each weighing 40 tons. Daily training in the nearby waters of Moreton Bay took the form of sea trials and testing of the barges in preparation for the landing of essential supplies for Allied troops in the war zones in the Pacific islands. When word reached the camp of the Japanese surrender in August, 1945, celebrations ran high over beers in the mess. The then commanding officer, a major who wore a revolver at all times, reportedly withdrew the firearm from its holster and fired celebratory shots into the floor as he approached the bar. The Toorbul Point area used for military purposes in WW2 was bounded by Pumicestone Passage, the area west towards Ningi, including today’s Spinnaker Sound and its environs, and the sloping land now intersected by Bestmann Road. A high-ranking army officer has estimated that the camp covered an area of approximately four square kilometres.