3 minute read

Marie Laurencin Sapphic Paris

Dylan Grossmann

This past Penn Parents weekend –between our gluttonous meals in Center City – I decided to entertain my parents by taking them to the Barnes Foundation, to show them the walls that cure my worst days on campus. Off we went to my refuge; I had practically memorized my route to view my favorite pieces, but my comfortable monotony was broken by Barnes’s sparkling new exhibition. “Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris,” turned my trite family outing, along with my understanding of modern art, upside down.

Advertisement

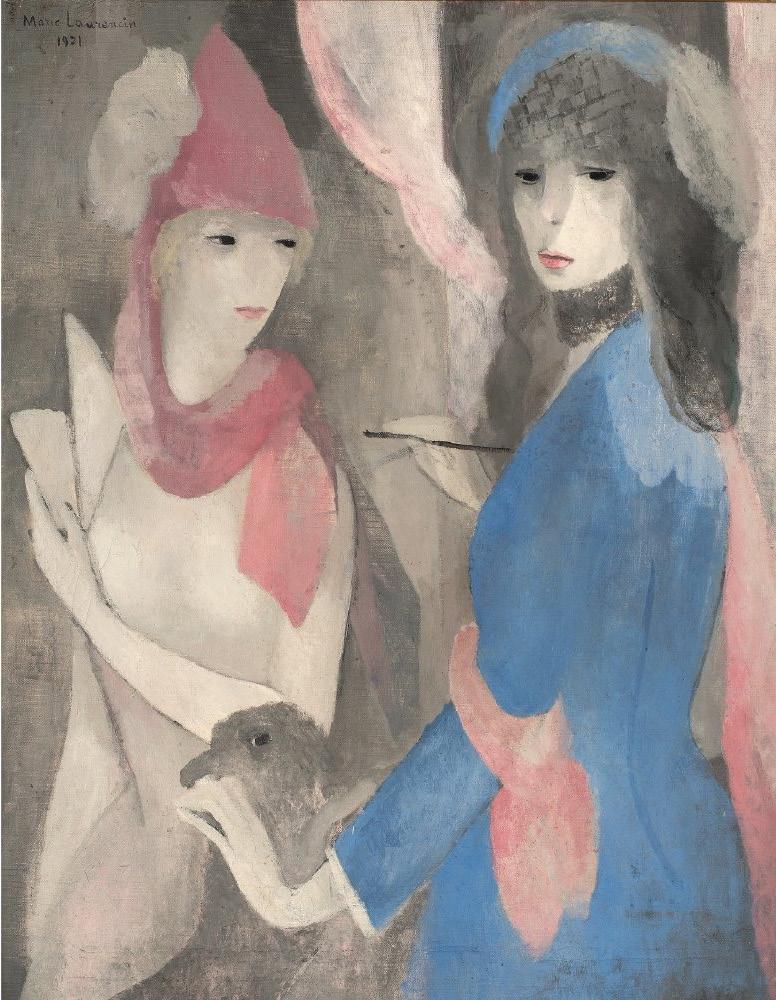

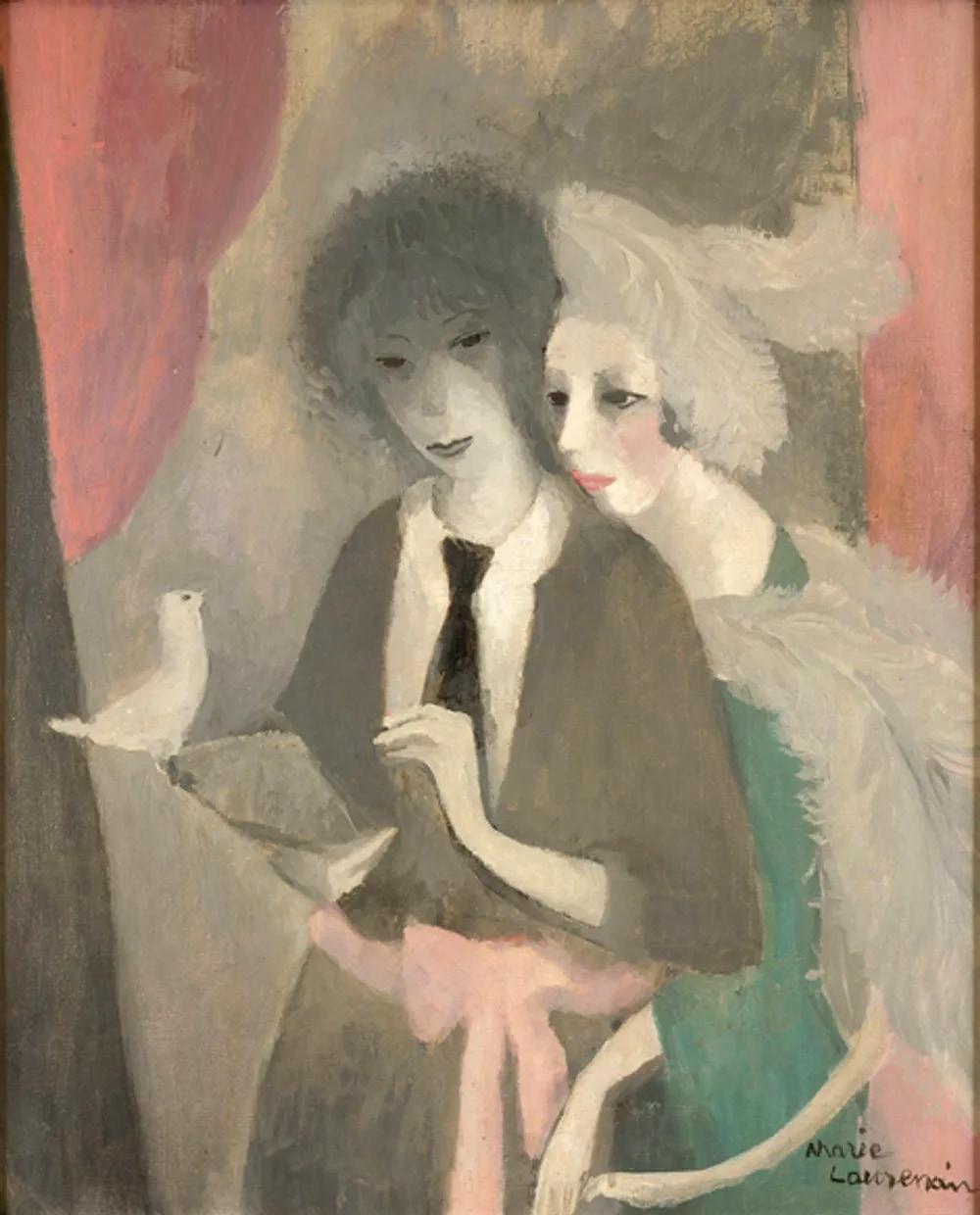

Immediately captivated by the exhibition’s drawing point “Laurencin’s World Without Men”, my mom and I stepped into the sapphic, ultra-feminine life of Laurencin. A jovial ambiance enveloped us as we viewed Laurencin’s self-portraits. I was enthralled by how she captured her changing self view through her chronological portraits, how her depictions not only followed the fluidity of her artistic voice but established her aura as deeply feminine, nearly ethereal. She skillfully highlights the most nuanced facets of her identity in each portrait – her suspected Creole heritage to her lesbianism – grappling with herself through a canvas medium.

Born in Paris as an illegitimate child to politician Alfred-Stanislas Toule, Laurencin had abundant access to a renowned art education. In 1904, she entered the Académie

Humbert where she met fellow students

George Braque and Francis Picabia, who introduced her to Pablo Picasso. In 1907, she became a part of Picasso’s artistic circle and joined the ranks of the top Cubist artists. The Cubist works shown at the Barnes were captivating in their dazzling femininity. Laurencin’s cubism was lush, dainty, and gentle in relation to her male counterparts. The female subjects of her works are shown in obvious relations, only the sharpness of the cubist style to subtle the sapphic undertones. I believe Laurencin’s works Le Bal élégant, La Danse à la campagne, and Two Women at Piano are decisively the pieces that warrant the name on the exhibition’s letterhead “Sapphic Modernity.” teamLab Borderless (rendering). © teamLab.

As we walked further, a small frame hung solo on the wall of the following room (an anomaly for the Barnes Foundation), flanked by Laurencin’s poem “The Sedative” and the description of her exile, The Prisoner II was a sobering contrast to the girlish femininity of her earlier works. While married to the German baron and artist Otto von Wätjen, she became a German national and lost her French citizenship. In reaction to WWI, she was forced to leave France, residing in Spain for five years. As being a Parisian woman was so deeply critical and foundational to her understanding of her identity, she spent her exile uninspired and in agony. The Prisoner II captures her deep despair, her lifeless portrait looking out from behind a chainmail curtain. Again, a testament to the fusing of her identity and her artistry.

Upon her return to her life in high society Paris, women involved in the same upper-crust Parisian circle as Laurencin commissioned her to immortalize themselves. Her portraits hung in a room fittingly titled Women Supporting Women, composed of impressively high society women such as steamship enterprise heiress Lady Cunard and Paris socialite Baroness Gourgaud. Most famously, her portrait of Coco Chanel shows the women’s-wear icon in a toneddown fashion, strikingly dissimilar to her historical other portrayals. Laurencin’s selfassured nature bled into her portraiture. As she depicted herself, she showed her subjects as they were, not who they were largely perceived to be. Finally, her portrait of beauty tycoon Helena Rubinstein, landed Laurencin’s work a spot in the most prestigious collection of modern art at the time — that of the sitter herself.

The prominence of “Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris” long outlasted our family outing to the Barnes Foundation; for the remainder of the weekend, Laurencin’s work filled the conversations and thoughts of my mother and I — reeling in the celebratorily feminine world Laurencin created for us. To a quick onlooker, her exaggerated femininity may have been just that, but open-minded viewers saw the underlying connection to queerness and womanhood. When you step into the exhibition, you step into Laurencin’s life, and you feel like you know her intimately after — the triumph of an artistic career.

Top: Marie Laurencin, Women with Dove, 1919. Centre Pompidou – Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Jacques Faujour / CNAC/ MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Bottom: Marie Laurencin, Portrait of Mademoiselle Chanel, 1923. Centre Pompidou – Musée National d’Art Moderne, Paris. © Fondation Foujita / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Jacques Faujour / CNAC/MNAM, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.