14 minute read

Withstanding the Test of Time

75 years of legacy, change and continuity -where

BY SHELLEY SALLEE, P h D, HISTORY DEPARTMENT CHAIR

“The coeducational idea sounds pretty darn good,” wrote a soldier in his response to co-founding Head of School Reverend William Brewster, who had sent him a letter soliciting a donation. This came at a time when the service member was encountering men who were treating women as “chattel.” Brewster “was aware of New England schools that had been single sex from the beginning and would never change,” and he also knew he must get others to believe in his bold vision. He wrote to everyone he thought might support a future school. When a trustee asked what they would do if “we do not get the 56 boarders,” Brewster responded that he was on his way to Lufkin and San Antonio, Texas, to talk to prospective families “the same way that a salesman does who believes in what he is selling.”

Brewster believed “that a Church school have in it both boys and girls of every economic and social group, that color of skin be no barrier, and that through constant common worship and emphasis on common purpose engaged daily by all, that a Christian atmosphere would prevail.” He did everything he could to put this vision into practice in what turned out to be the last few years of his life. His funeral was the first service in the new school Chapel.

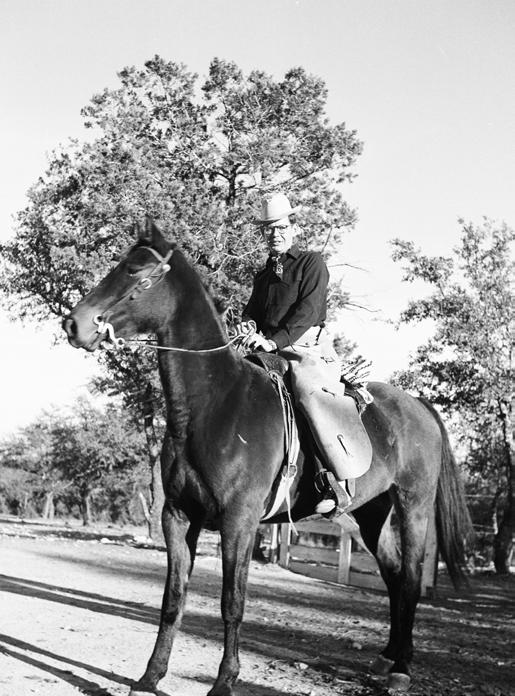

When the school opened in the fall of 1950, the campus had a horse corral before it had a phone. The first class of Spartans recognized “it was a year of trial to see if coeducation would work out.” Fast-forward into the future, and in 2025, horses and rotary phones are considered vintage, and smartphones and artificial intelligence dominate the world’s landscape. The school’s 75th anniversary appears to celebrate change over continuity. The founders were pioneers. And they wrote, “To the future students, we pass on this challenge to live up to the ideals upon which the school was founded.” The decades that followed are a testimony to the school’s continuity of meeting that decade’s trials while also trying to live up to its founding ideals.

1950s: Out of the Ashes of War

“That’s where I want it.” The late Elizabeth Brewster recalled her husband gazing across the Colorado River at “The Hill.” Brewster, influenced by Reinhold Niebuhr, the leading theologian known for his prophetic urging of intervention in Nazi Germany, had a big vision for a scrappy landscape. A new type of school community seemed to be what he felt the world needed when he declared St. Stephen’s would be “dedicated to the recovery of humans.” Brewster’s vision motivated him to join the Rt. Rev. John E. Hines, then bishop coadjutor of the Diocese of Texas. They viewed a school that offered “intellectual honesty and curiosity ... the wrestling with social problems” as hope for the world.

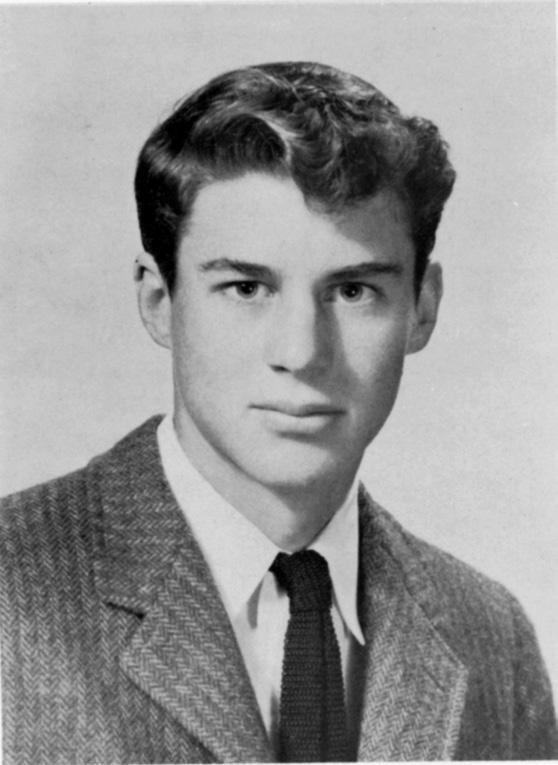

To his son, Will Brewster ’51, and his friend Cliff “Toppy” Castle ’51, whom Brewster recruited from the Kent School in western Connecticut to be in the first junior and senior class, the vision surely looked different. They had given up ice hockey and crew to go to school on an overgrazed goat ranch where cedar choppers once lived.

Some boarding school etiquette traditions were transported. When girls boycotted wearing hats to chapel, they were reprimanded. Boys had better luck when they petitioned to be allowed “to wear clean Levi’s to school.” Yet coeducation in a boarding school introduced an egalitarianism ahead of its time, or at least ahead of the boys’ schools of New England. Robin Carter Kennedy ’59 recalled, “I never felt that you couldn’t

1959

1950s

On December 26, 1949, co-founders the

1966

1969 speak out and do what you wanted.” The late Ann Mills Weaver ’56 once noted that girls and boys often developed close, nonromantic relationships discussing “fine points” about religion and philosophy in the “smoking lounge.” It helped that both sexes were needed to fill teams. The 1952 yearbook reported, “No trophies were won in baseball, but both boys and girls participated with wonderful team spirit.”

Stories of student work crews hauling rock have grown as tall as some of the buildings. There was a clear sense for the small early classes that they were part of building something new.

The Army acquaintance who had expressed being “amazed at the number of fellows who have never known girls as people” could now see that at St. Stephen’s, Brewster’s reformist vision was working.

1960s Civil Rights: This

Integration was a founding vision of Brewster and Hines, who marched beside Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., but it took a decade to begin. Before he died in 1953, Brewster wrote that in “church schools,” we should “insist” that “racial background is no barrier.” A visit to Austin, where a minister offered a Black family communion only to have no one else join them, had become a personal test for his church school to be different.

Born in South Carolina, Hines had been attacking racism since seminary and went on as bishop of Texas in 1955 to lead the diocese through racial integration of its institutions. Yet he and Brewster realized what they were up against.

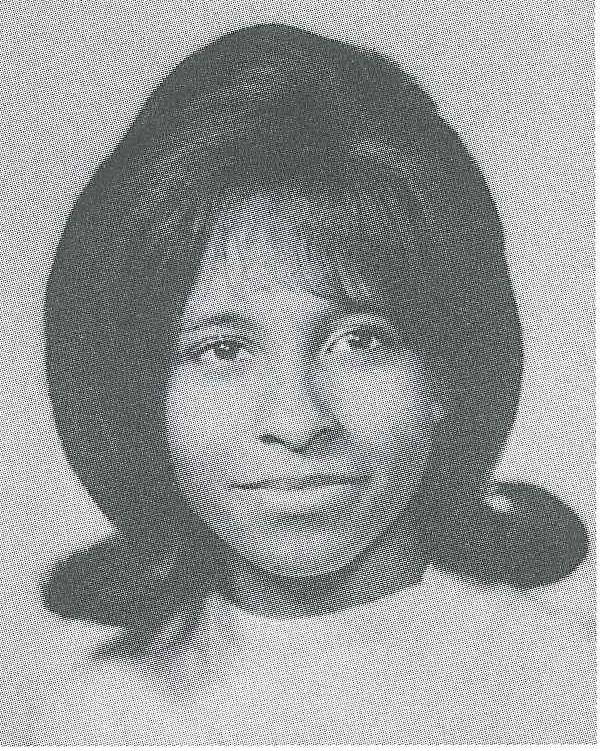

The school found allies. Dr. Allen Becker became head of school in 1957 on the condition “that racial discrimination should be eliminated as an entrance criterion.” He led the fledgling school through desegregation, but it took the late

1972

Bertha Sadler Means, a congregant at St. James Episcopal Church in East Austin, who had led desegregation fights at the local skating rink and public swimming pools, to make it happen. Her daughter Pat Means King ’66 became the first Black graduate. Means and her husband, Dr. James H. Means Sr., helped recruit Theodore Smith, the first Black teacher at St. Stephen’s, to be head of the Math Department.

In the first years of integration, there were very few Black students, but from 1967 to 1975, the Anne C. Stouffer Foundation in North Carolina promoted “the integration of preparatory schools in the South,” and the Rio Grande Valley Scholars Program sought to connect Hispanic students to preparatory schools. St. Stephen’s partnership with these funds lifted the school closer to Brewster and Hines’ vision.

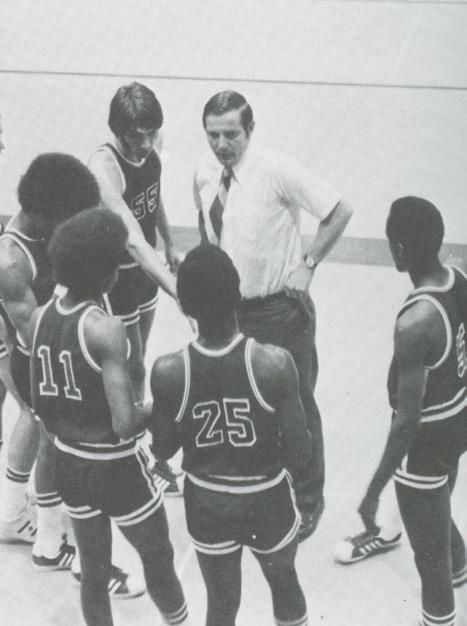

In 1972, when the school fielded a basketball team with five Black players and traveled with a cheerleading squad of six that included two Stouffer scholars and a Valley scholar, they decided to embrace being race rebels in the athletic conference. When the St. Stephen’s team entered the gym “led by a Black team member holding high a ball painted in alternating sections of Black and White,” Spartan fans were moved to tears, with one remarking: “This is what we do.”

While a few parents balked and a few donors withdrew support, students led. While the outside scholarships dried up in the mid-’70s, students continued to raise money for the Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship, which John McFarland ’68 and Clarke Heidrick ’68, P ’02, ’05, ’10 established to honor the slain leader. Rudy Green ’71, P ’07 of Fort Worth, who had never been to Austin and had always attended segregated schools, became the school’s first MLK Scholar. Later, as a trustee and Spartan parent, he helped raise funds for many more MLK Scholars.

“The Times They Are A-Changin” could

1970s be heard from a dorm window. A love-in blossomed one warm spring day. Legend has it that a group of students, while meeting with school counselor Nadea Gizelbach, thought it would be great to get everyone to hug each other. They began entering classes and pulling friends outside to hug. Soon a large part of the student body ended up in the pool, hugging.

If James Hinton Sledd, Jr.’s 1969 graduation speech is any indication, the decade closed with Spartans engaging the social justice issues of their times as Brewster had imagined. Sledd, with passion about the concerns raised by the New Left and Black Power, issued a generational demand. He told students they “have the power to change things, and to give youth the direction it needs.”

Adults were trying. In 1968, after Gregory Hicks ’68, the school’s first Black boarding student to graduate, gave the senior address, the visiting chaplain played a Simon and Garfunkel song before his concluding graduation prayer:

May God give you a groovy life And may you find such a life By spending yours helping Him Make a groovy world for others. AMEN

1970s: A Chance to Be Yourself

Building St. Stephen’s in the ’70s involved self-expression, growth, creativity and tragedy. The 1972 yearbook page titled “A Chance to Be Yourself” suggests the period’s new challenges to authority. Yearbooks show students wearing the era in their expressive clothing choices, but whatever new rebellions arose, consequences followed. “If you got in trouble, you got to build a sidewalk,” Jim Crosby ’70, P ’00, ’02, ’05 recalled. On December 23, 1973, fire destroyed the Gillette Dorm. Faculty members in apartments attached to the dorm lost everything. A parent sent Christmas ornaments to the faculty families, and another offered an Indian basket to help history teacher Kathryn Respess “start again her destroyed collection.” In the spring, construction began on a new library student center (later named Becker Library).

With a direct link back to the founding vision for the “recovery of humans,” the Japanese Exchange Program was established in 1973, and its first students were Yoshinori Yokoyama ’74 and Tsugunori Yasuda ’75. The program was initiated by the late Dean Towner, a Latin instructor and former U.S. Navy lieutenant who served in Okinawa and Japan as a translator and interpreter. He wrote, “These young men ... will not make war on each other, as my generation did.”

1980s: Tight Budgets and Growing Pains

“Budget: ‘Tight and getting Tighter,’” the 1987 trustee minutes sounded an alarm. Texas history and a pivotal stage of school history tested St. Stephen’s survival as a boarding school.

While the 1970s energy crisis dragged down the national economy, in Texas, by contrast, the Arab oil embargo fueled an oil boom. According to the Texas Tribune, West Texas locals “nicknamed two-seater Mercedes convertibles Midland Mustangs,” and into the early ’80s, the school’s dorms were packed.

The oil bust hit Texas in the 1980s, as did the savings and loan crisis. In 1987, the school year began with “25 empty beds” and was almost half a million dollars short. Deficits and a “decline in boarding” continued into the early 1990s. By 1991, the school body, primarily boarding students in its first two decades, had an enrollment of 98 boarders and 162 day students.

With the Pennybacker Bridge completed in 1982, expansion of the Loop 360 highway also drove school trustees to undertake “the Davenport land trade” to stop a high-rise looming over the athletic fields and to “ensure the setting so critical to the school’s purpose and character.”

Additionally, hard times challenged efforts to increase diversity. Debate arose over whether the school “could afford scholarships.” Trustees ultimately preserved the integrity of the campus from developers and committed to scholarships.

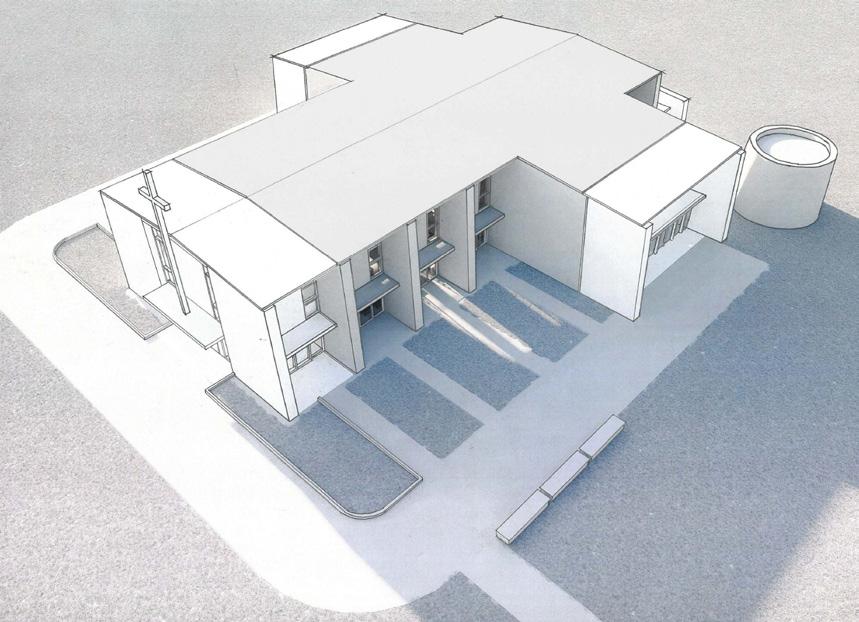

In 1988, trustees took a leap of faith and hired architects for a campus site plan. That year, records show the school had a deficit of $418,000. Some of the first students who hauled rocks for the buildings and walls of the school, now as adults, converted that strength to carry heavy fiduciary responsibilities. Nancy Wilson Scanlan ’59 chaired a trustee committee focused on the “future of the Middle School,” with the question of whether it should exist and, if so, whether it should be expanded.

With the help of many generous

1982

Students register for classes at the start of the academic year donors, including lead gifts from the T.L.L. Temple Foundation and the Episcopal Foundation of Texas, the school began plans for a new fine arts building and the renovation of the Ives and Freeman dorms, which were built as “temporary army barracks-type” dorms. The board instituted a cash-and-carry policy to have all funds in hand before construction began, even though that meant the fine arts building remained a dream.

1990s: Heading to Seoul Saves the Soul of St. Stephen’s

“If you don’t learn how to use chopsticks, you’re going to starve,” advised Sarah Todd, international program director to associate head of school for enrollment management Lawrence Sampleton before his first trip to South Korea. In a 1999 yearbook, Chul Ho Kim ’00 wrote about the day you first meet “big Mr. Sampleton.” Todd’s simple chopstick advice to her All-American University of Texas football star colleague to stay nourished could be a metaphor for

1990s

defining changes during the 1990s that helped revive the boarding program.

Head of School Frederick Weissbach’s charge to “save the boarding program” generated initiatives and the recruitment of a new generation of school leaders like Sampleton and Todd, who are still working at St. Stephen’s today. International boarding students were not the only new boarders. Weissbach initiated “interns,” and in 1993, Yvonne Adams, girls varsity basketball coach and later the school’s first director of equity and inclusion; Gene “G.P.” Phillips, director of residential life; and Athletic Director Jon McCain, who all grew into leadership roles, arrived. “We slept in dorm rooms,” Phillips recalled.

Tabor Academy student Daigo Satoh ’03 says the head of his school’s international office gave him the green light to transfer to St. Stephen’s because she was acquainted with Todd, who knew Satoh wanted to play year-round soccer. By the decade’s end, the school established tennis and soccer academies with a budding international program that positioned St. Stephen’s well for when China opened up to recruitment in the early 2000s.

A new generation of faculty created new programs. In 1994, science instructor Dr. Frank Mikan arrived and helped the school break ground on the observatory, getting students excited about studying star clusters, planets and galaxies.

Later in 1996, the Devil’s Canyon Wilderness Program provided more opportunity.

“Caving is like being on another planet,” said Alyssa Lowe ’98, former Devil’s Canyon Wilderness Program team captain. Today, the program is called the Devil’s Canyon Adventure Program, and under the guidance of robotics instructor Troy Lanier and Charlton Perry, director of outdoor education and land management, the program has evolved and expanded to include trips to the Rio Grande and elsewhere. Kim Garey, current associate head of school for academics and student programs, and her husband, Leadership Giving Officer Clay Nichols, who started the Theatre Focus program, became as immersed in boarding culture as their mentors Dobbie Leverton Fenton ’63 and Alan Fenton. Many new faculty came, created and stayed.

By fall 1996, when Sampleton became the director of Admission, enrollment soared to 538 students from 40 different towns and cities, 13 different states and 16 different countries. Boarding had increased by more than 50% since 1987. The admission team “became more selective,” and the “number of minority students more than tripled.” Transitions entailed a learning curve and controversy, but Sampleton notes that today “schools all over the United States would love to have the Soccer Academy because recruiting domestic boarders is hard, and our Soccer Academy has attracted so many.”

Boarding was back, but overall, the school needed more buildings. In October 1993, St. Stephen’s dedicated the Helm Fine Arts Center, and “Our Town” was the first play in the Temple Family Theatre. Fine Arts Chair Liz Moon remembers a colleague saying, “If we don’t build the fine arts building, we’ll have no credibility with donors.”

By 1993, a Middle School that had been on The Hill in a dilapidated building with a few dozen students had its own Gunn Hall, located in the converted dining hall. The Middle School division became foundational to the stability of the school, with plans to add 8th grade boarders and some of the school’s most enduring traditions like the 8th grade trip to Big Bend National Park. 1996

1999

Students enjoy using the

Development came at the cost of mounting debt, but the decade put the school on track for the future.

2000-2025: Children of Globalization

Former Head of School Bob Kirkpatrick recalls, “the early 2000s was a tough time for St. Stephen’s with a lot of financial issues.” But when Kirkpatrick joined the school in 2007, he did so harnessing hope and possibility. Kirkpatrick says he and then Director of Advancement Christine Aubrey rallied with the full board, staff, parents and the entire St. Stephen’s community to launch the $28 million Frame the Future campaign.

“We really wanted to usher in a period of growth and stability and the best way to do that was a successful campaign,” said Kirkpatrick. “We had done our homework and we knew we had the courage to do it. Frame the Future helped set the stage for what was possible.” The five-year campaign reached its lofty goal in just under four years, turning the school’s future financial tide in a better direction. The campaign allowed the school to build the dining hall, the student center and more.

“The community was incredibly resilient with lots of generosity and commitment,” said Kirkpatrick.

By the 21st century, a two-race system no longer defined U.S. society or St. Stephen’s. The school had diversity within its diversity. In 2010, Black students, led by Lynden Pindling ’09, grandson of the President of the Bahamas, and Ikem Leigh ’10, whose parents were working in Swaziland (now Eswastini), started a Black Culture Club and invited all students. It was a sign the school needed more leadership in the area of diversity and inclusion. The late Yvonne Adams stepped up to be the school’s first director of equity and inclusion, helping the culture of the school keep pace with supporting students.

Globalization not only diversified the student population in wonderful ways, but it also boosted student interest in being global citizens. The Rev. Roger Bowen, a former Peace Corps volunteer and head of school, partnered with the Episcopal Diocese of Haiti in 2003 to support St. Etienne, a school in Salmadère, in the remote Central Plateau of Haiti. As St. Stephen’s celebrated its 20-year partnership, Henry Sikes ’11 remembered: “It made me learn to love the person sitting next to me, whoever they are.”

“Going to Haiti and learning about Dr. Paul Farmer and his work at the Zanmi Lasante” is what “really got me interested in global health” and medical school, wrote Sarika Mullapudi ’17. While the school had a long tradition of study in Salamanca and León, Spain, and had various trips to Europe, options expanded. Before political turmoil made it too dangerous to take students to Nicaragua, El Salvador and Haiti, specialized trips, born out of St. Stephen’s relationships with people in those countries, developed.

Globalization brought new diversity and new expectations for learning and for staying connected to friends and family regardless of where they were in the world. No one expected that the children of globalization would face a pandemic test. Head of School Chris Gunnin, in Disney World over spring break, knew he had to make a tough call when officials closed the park. “At that time, I thought it took a lot of courage just to make the decision to close for two weeks,” he recalled.

Spartans had to ramp up their global connectivity to stay together as a school community. No one had imagined virtual learning, but everyone figured it out. “Mine were befuddled,” wrote history and geometry teacher Christopher Colvin in the early days in a virtual department meeting where teachers shared ideas about how to make it all work.

Gunnin remembers how Chinese families sent masks and other supplies, and alumni and parents shared medical expertise and even access to a lab so that twice-a-week COVID-19 testing could take place and make in-person learning an option sooner than at many schools. Some international students could not go home for over two years. Sitting at her kitchen table in Lagos, Nigeria, new student Valerie Emioma ’22 met her advisor virtually on the first day of school in the fall of 2020. The children of globalization passed their hardest test.

Timeless

In an interview before he died, Bishop Hines said, “there isn’t any such thing as a riskless Christianity.” When he said that, he could not yet imagine that at a graduation ceremony would be parents who crossed oceans with buried fears of a generation who survived the Chinese Cultural Revolution or parents of every child relieved to be at a place that celebrates their child for being themselves. The school they created for the “recovery of humans” does its part by giving young people a place to be loved, to learn and to be known, regardless of the challenges of their era. May’s senior graduation speaker, Charlie Hubbard ’25, in his list of words about the school, included “timeless,” and it felt that way in the Chapel filled with generations gathered for the sacred hug of that rite of passage.