6 minute read

The School Play

from Jan 1941

by StPetersYork

ally) ensured with scrupulous thoroughness that any linen which may have been soiled in the course of the play is returned suitably laundered. But in this case, D. G. Middleton, who had to shoulder the responsibility, was more than equal to the occasion and, with the invaluable co-operation of the other actors on a full stage who, whi'e they had only rare lines to say, did not forget to act, successfully avoided the very real danger of the play petering out.

Apart from its general excellence as comedy, " The Sport of Kings " had the advantage of giving scope to an exceptionally large cast, and the experience gained by the players (many of them very young) will prove invaluable in the future. Almost none of the actors had appeared previously in School plays, and it is greatly to their credit that their inexperience could hardly have been apparent to the audience. For the years immediately to come there should be no dearth of talent.

Indeed, the generally good quality of the acting was one of the satisfying features of the play. The smallest parts were played better than competently, and there were none of those inequalities which are so often manifest in large casts. The play never flagged when the minor characters were left to hold the fort. The performances of D. C. Thompson, as Cook (Providence built him for the part), and Hodgson, as the Parlour Maid, and of Harper, as the tearful tweeny, received a thoroughly deserved recognition from the audience. And for their brief appearances in the opening scene, Byass (the Barmaid) and A. G. Reynolds, as the Newsboy, were quite adequate. Pryer was convincing as the Police Sergeant, a small part which he combined with some invaluable service behind the scenes.

It would be invidious, and, indeed, difficult, to attempt to differentiate between the performances of those who bore the heat and burden of the day (or rather night). D. G. Middleton, as Algernon Sprigge, played a most important part extremely capably and, particularly at the second performance, when he had got into his stride, acted with the freshness and life which the role demands. Dench played what was perhaps the most difficult part in the play —that of Amos Purdie—with conspicuous success. He has genuine ability which is bound to develop as he gains further experience. The observation that very occasionally he played too long on one note and tended here and there to repeat gestures unduly, implies commendation rather than 21

criticism. The part called for exceptional versatility, and the fact that his lapses were rare and that he succeeded far more often than he failed in achieving that most difficult thing in acting, the expression of light and shade, is a real tribute to his performance. In the episode at the close of the second act he succeeded, with the equally strong cooperation of Long, as the Butler, in carrying through a most exacting scene with flying colours.

Long, indeed, was an unqualified success as Bates. He played confidently throughout, and his transitions from the sycophant butler to the ex-bookie's clerk were always natural and convincing. Moreover, there were times when he allowed the reality of " Bert Briggs " to show through the veneer of the sanctimonious and obsequious Bates in a way which showed a true subtlety of interpretation. And he made telling use of gesture, movement and facial expression, holding them long enough and making them sufficiently decisive to be really effective. In this respect he set an example which some of the other players might have followed with advantage.

Particular credit was due to Webber for the success he made of the part of Dulcie Primrose. The playing of female characters by boys is beset by initial difficulties before " acting " in the ordinary sense can even begin, and in Webber's case they were greatest of all, in that his part was a " straight " one with no marked " character " to help it along. It is difficult to imagine any boy making a better job of it than he did. The inevitable incongruousness never obtruded, and even in the acid test of the romantic passages he pulled it off. There were others who may have made their parts more obviously effective, but in many respects Webber's was perhaps the most sustained and intelligent piece of acting of all.

The efficient playing of the female roles was not the least important contribution to the production. J. E. Thompson, as Katie, left little to be desired. His complete naturalness and his ability to act with every part of him made his spirited rendering of Mr. Purdie's tom-boy daughter one of the good things of the play. G. E. K. Reynolds, too, never faltered as Mrs. Purdie. He was always telling, and put over his few scenes with real effect.

Denby, as " Toots," the foil to Sir Algernon Sprigge, contributed some excellent work. It was a part which lent itself readily to parody, but Denby, very creditably, played with the necessary restraint and was thereby the more

22

effective. He almost always got his laughs, and there is no doubt that by his lively enthusiasm he helped along many difficult scenes. Denholm, as Joe Purdie, made a good partner to Katie, and, if his part was of the sort which should come most readily to a boy, he deserves every credit for the easy naturalness with which he played it.

Ping, as " the real Panama Pete," showed conclusively that he has in him the makings of a good character player. At times there was a slight tendency to over-act his part, but it was barely perceptible. He thoroughly understood the role, and there is no doubt that his breezy entrance fulfilled the author's purpose of administering a tonic to the third act just when it was in need of it. Lastly, a word about " Albert " (T. C. Middleton). Like " Joe," this part gave a real opportunity to a boy actor, and Middleton took it. There was little to criticize in his rendering except an occasional inaudibility, against which he should guard in future.

Most certainly the play succeeded in the prime function of comedy—that of making an audience laugh. The company would have done still better in this respect if they had had sufficient experience to wait longer for the laughs. In general they did not offend greatly in this, but there were times when incipient laughs were nipped in the bud by overeagerness to get on. Occasionally, too, good comedy lines were " thrown away " when they ought not to have been— presumably because the actors, inevitably staled by rehearsal, had ceased to see that they were funny. Conversely, however, good jokes which were well and efficiently " plugged " fell on stony ground. But that is the inevitable lot of comedy actors.

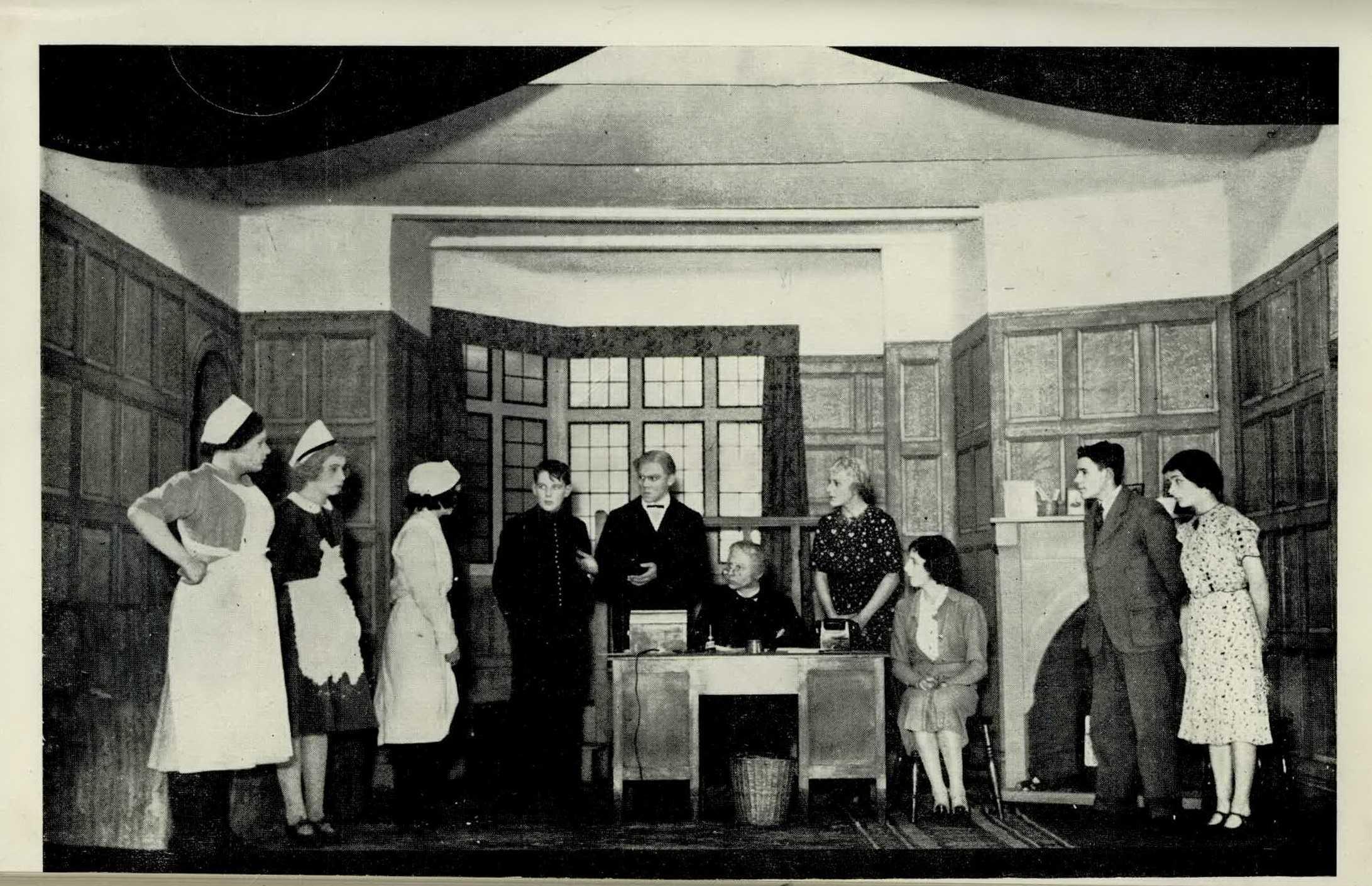

Mechanically the performance rarely faltered. In a play of this type, slickness and good timing are of paramount importance. The timing was usually good, no entrances or exits were fluffed, and no " business " bungled. The general smooth running of the play was a creditable feature. None of the hitches which might so easily have happened in a rather complicated production occurred.

The actors were particularly fortunate in one most important respect. They had the advantage of an excellent set. For this, Mr. P. P. Noble Fawcett, who designed it, deserves our heartiest congratulations, as do his helpers, Schofield, Miller and McKinlay. It is but rarely that one sees so good a set on an amateur stage, and Mr. Fawcett's interior at " Newstead Grange," executed with the skill and attention to detail which we now expect from him, 23