36 minute read

Drama

Thursday 2 September

An email just in. It’s from Mr Dormandy. He’s put out an open call to the Eighth Form: does anyone want to learn to be a theatre director? Do I? Is the sky blue?

Friday 3 September

I have recruited my team. The play is fabulous, the actors even better. An amalgamation of scenes and speeches from Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead to be performed by two of St Paul’s’ most in-demand actors: Mr Benny Harrison and Mr Elijah Patterson.

Saturday 4 September

Now begins the process of script editing. This is gratifying, but tedious work. Due to the nature of the play, there are many moments where the two principal characters are left alone onstage to… ruminate… and gesticulate… and search the depths of their souls and comparatively less deep brains to… fill the time… and end the monotony. The audience is allowed to see the human condition when subjugated to the single worst feeling on earth: boredom. By the evening, my script edit has been completed. My homework, however, has not fared so well.

Sunday 5 September

I am emailing. “Dear Mr Dormandy,” I begin. A pretty good start. Some purple prose follows that expresses my desire to be a part of the Young Directors’ Showcase, detailing my play choice and cast. By ten o’clock he has responded: we’ve got the green light. An exuberant “WOOOHHHOOO” is sent to the WhatsApp chat, a sentiment quickly echoed by my equally keen cast. Young Directors’ 2021 has started.

Monday 6 September

Let’s get organised. I ask Benny and Elijah’s tailors what sizes they wear. They respond “large? maybe? It depends. Let’s go with medium.” It would appear Saville Row has lost its touch.

Tuesday 7 September

I need a concept. Something intriguing, cheap, and well suited for the play. The action takes place as the pair are undertaking a quest on a royal summons to attend the King’s castle. How do I show this? I give the brain a squeeze and a few creative juices drip out. I have this strange concept of the Teddy Bear’s Picnic in my mind. No. That’s silly. Think of something better.

Wednesday 8 September

Teddy Bear’s Picnic it is! I’d like a blanket, basket, pillow and… dungarees. Fun, colourful, wacky, unconventional dungarees. It has that unusual, intriguing quirkiness that I appreciate aesthetically and seems apt for the characters’ dispositions.

Thursday 9 September

I send an email to Cait, our Theatre Technician, who is very kindly helping us. I am rapidly realising that directing is 90% admin. In this instance, the admin in question is a list of props and costumes. I am a great fan of plays with things: stuff to look at and be intrigued by.

Friday 10 September

The deadline to enter Young Directors’ has officially shut. I wonder who else is performing?

Saturday 11 September

Cait has secured our props and costumes; they are waiting in one of the iconic plastic containers. The one outstanding item are those wacky dungarees – those bright, bold, garments that will make the characters really pop onstage.

Sunday 12 September

I spend the last day of the weekend re-reading the play. I forgot just how intelligent and witty it is. Then I watch the 1990 movie adaptation directed by Stoppard himself and starring Gary Oldman and Tim Roth. Delight turns to dread: how are we ever going to match that duo? Dungarees are still missing.

Monday 13 September

Dungarees are secured. I sleep easy.

Tuesday 14 September

Another email, this time from Mr Anthony. The task? Produce a poster to advertise the showcase that hasn’t even begun rehearsals. Something vague enough that it captures Theatre as a whole, but not too vague so that no ➦

one knows what is actually being advertised. Obviously it had to be in artsy black and white, that’s a given. But something eye-catching… Hmmm.

Wednesday 15 September

Update on the poster: it isn’t quite monochrome. A focal point of red from a theatre ghost light – if you don’t know about these, look them up. I promise they’re interesting.

Thursday 16 September

To add to the fantastical style I am aiming for, I think I need to be bold with my lighting and sound choices. A kaleidoscope of fuchsias and cyans. Obnoxiously positive calliope music to set the tone. Gorgeous!

Friday 17 September

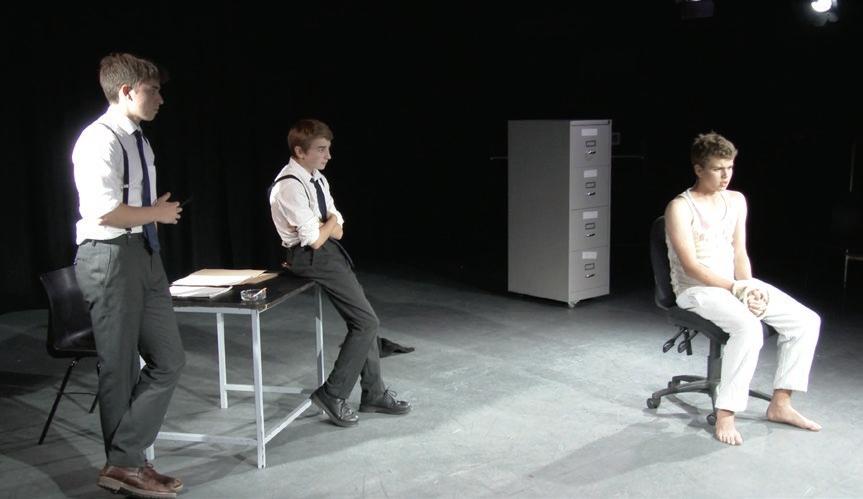

After school in DR3. Be there or be square. We three directors (Leo Odgers is doing The Pillowman by Martin McDonagh and Harishan Ganeshan is tackling Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar) are treated to a crash course in directing by Mr Dormandy. Covering both the practicalities of production and creative side of the role, we go through three years of training at RADA all in one evening.

Saturday 18 September

Bright, but not too early, directors and cast descend on the Milton studio. We are lucky enough to have two theatre professionals coming in. The morning is spent with Anna Healey, who uses the four natural elements (fire, water, air and earth) as a way of creating instant characters. From dance to stylised movement to caricature to realistic people, Anna is amazing, providing an alternative and more intuitive perspective from which to approach creative work. Following a meal deal lunch (I have chicken Caesar wrap, salted popcorn and a coke –anything else is objectively wrong), Roberta Zuric leads a workshop teaching us how to approach blocking a scene. The two main points I take away are that you must be willing to experiment and that the best blocking is so well justified that if the play was suddenly muted, the audience would still understand the dynamic between the characters. Roberta does say we are allowed one thing just because it’s cool though.

Sunday 19 September

Independent rehearsal time. Six hours of work. Well… more like one hour of work, two hours of chat, and three hours looking for those dratted coins – we use at least fifty in the show – that decide to plunge themselves into only the tightest of crevices.

Monday 20 September

I realise now that perhaps rehearsals on Sunday might have been best spent rehearsing, not chatting. Panic sets in.

Tuesday 21 September

It is in these final few rehearsals that everything starts to come together. Little details are added that colour in the sketch we have created thus far. My actors are beginning to get nervous. I am not. They’re going to smash it.

Wednesday 22 September

Now we tech! With lights, sound, costume, and props it doesn’t look half bad. Cait has done absolute wonders with the lights; the stage has that dreamy, mystic quality that I had wanted since the very beginning.

Thursday 23 September

AAAAA EEEEE IIIII OOOOO UUUUU. Don’t mind that; we’re just warming up our voices and bodies. Tonight is the night: show number one! I can see the determination in Benny and Elijah’s eyes. (And stretch down to the ground). I am so proud of everything they have put into this showcase. Utter professionals. True friends. (red lorry, yellow lorry, red lorry, yellow lorry) Never a dull moment, it’s just been fun fun fun and continues to be so all the way to the finishing line.

Friday 24 September

Following last night’s success, I cannot wait to watch them do it all again. It went perfectly on Thursday, what could go wrong…? Ping… Ping… PING. Who’s messaging me? Oh… Ah… Oh… Hm… Benny has lost his voice. I wait till he gets into school to hear the damage. It would appear that overnight he has run several marathons and smoked a forty-year supply of cigarettes. After much honey, Lemsip, and hot water, his voice is as clear as it ever will be. This is what I love about theatre: the unpredictability. Something always goes wrong and the joy is in finding the solution. Having sneaked hot water onstage in a hip flask stowed in his picnic basket, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern step out on stage for the final time. Take your bow, gents. You deserve it.

I’d like to use this column space to briefly pay tribute to everything that SPS Drama has done for me over the past five years. I could not have asked for a more enjoyable experience. Both in academics and extracurriculars, the entire department has been phenomenal. Christian Anthony, Simon Dormandy, Dan Pirrie, Alex Kerr, Edward Williams, Tilly Woodhouse, Alberto Lais, Tom Chamberlain, Natalie Evans, Dan Staniforth, Darren Mitchell, Cait McGregor, and Natalia Alvarez – THANK YOU SO MUCH. There is no doubt that I will treasure my days in

the Pepys for the entirety of my life. ❚

Imp Soc

Elijah Patterson

Like the little lamb in the spring fields, ImpSoc has bounced back this year with a completely new committee, after two long years of COVID restrictions. We started with the hysterical ImpSoc 15th anniversary show, involving a series of classic ImpSoc games, such as Party Quirks, an entirely Improvised twenty minute play, and a superb free-style from none other than professional Improviser ‘MC Hammersmith’ himself. However, the most important achievement of the evening was proving to disbelievers that ‘orange’ is in fact rhymable.

In our weekly ImpSoc session, we have continued our tradition of extremely thorough planning beforehand, as opposed to making up games on the spot, which would be quite ridiculous and chaotic. Despite the rigid order, each session has nonetheless produced a broad range of the good, the bad, and the ugly jokes, as well as recurring old ImpSoc classics, such as ‘moon’ and ‘why are you naked?’ The former is certainly an inside joke, that may not be funny to most of you, but trust me when I say that it is, in fact, very, very funny.

The committee has been hard at work, 24/7/365 in fact, coming up with new roaringly-successful games. Starting with the ‘Huh?’ game, birthed from the genius of Ryan Davey, which involves participants wearing headphones during an improvised scene, such that they cannot hear each other and rely on lip-reading to decipher the meaning of the scene, and ending with the ‘Object Manipulation’ game, which is selfexplanatory. To some this may seem as though we have not come up with much, as there are only two; they would be wrong, however, as all good things come in pairs. Wings, for example, are better in pairs, and as such, with this badly constructed metaphor, ImpSoc will continue to soar into the stratosphere of satirical sophistication. Quite proud of that one actually.

To end this rather waffly and badly written (one could say it is improvised, ha) piece, and push this over the required word count, ImpSoc has been a thoroughly enjoyable experience this year, and the highlight of many a week. ❚

King Lear: Director’s Notes

King Lear begins and ends with a cautionary note on the dangers of speaking. Cordelia, realising that the currency of language has been debased by her sisters’ inflated rhetoric, refuses to extemporise on her love for Lear and instead explains that it is Goneril and Regan who have used language to say “nothing”. At the play’s close, Edgar advises those still standing to “speak what we feel, not what we ought to say”, reminding us that language is always performative, that social context often strangles self-expression, and that the spoken word is, like Wilde’s truth, “rarely pure and never simple”.

And who would know this better than a community of aristocrats knelt anxiously at the feet of a king whose capriciousness precedes him? In this, Shakespeare was merely reflecting the mechanics of the Stuart court, an obsequious sequence of metaevents in which courtiers were repeatedly called upon to demonstrate their proficiency in what they “ought to say”, in exchange for patronage and influence. James I was notorious for promoting handsome male favourites, men such as Robert Carr and George Villiers, who publicly flattered the king; for his efforts the previously cash-strapped Carr was gifted Sherbourne Castle and the post of Lord Chamberlain, whilst Villiers (when Carr fell out of favour) was made Earl of Buckingham and referred to by the monarch as “my sweet child and wife”.

No wonder, then, that emotional honesty and the very act of speaking is so frequently policed in King Lear. Indeed, the play is bloated with the conversations its characters fail to conduct: Lear provides scant reasoning for his abdication and refuses to explain his rejection of Cordelia to either France or Burgundy; Oswald denies Lear conversation, following Goneril’s instructions to ignore him; Lear discourages both Kent and the Fool from voicing ideas he does not wish to hear; Edgar is prevented from communicating with his father and godfather during his time as Poor Tom; Edmund refuses to confirm his romantic and political allegiance to either sister (when Goneril raises the subject, she then instructs him not to respond); Regan and Goneril repeatedly refuse to discuss their poor treatment of Lear with Albany (who, when his wife openly demonstrates her love for Edmund, threatens to stopper her mouth); and, at the play’s climax, Lear baulks at his daughter’s suggestion that they debate their fate with her sisters.

This reticence even permeates the theatrical experience itself: unlike Hamlet, Macbeth, Richard III, Othello, Leontes, Timon, or the Duke in Measure for Measure, Lear never addresses the audience directly, never entrusts us ➦

with his thoughts. It is left to the subplot’s warring brothers to keep us posted on their position within the play’s fractured cosmos (Edmund, like Iago before him, swells with Machiavellian pride whenever he breaks the fourth wall but is often circumspect in dialogue with others) for, when it comes to the groundlings, Lear refuses to “cleave [his] heart into [his] mouth” and instead says “nothing”.

On the heath however, shorn of social context and the responsibility of public performance, Lear loosens his tongue to voice a series of political and personal truths but is, ironically, condemned to monologue. Surrounded by a cast of characters adopting falsified voices (the disguised Kent, the performing Fool, the possessed ‘Poor Tom’) dialogue becomes impossible; the stream of words spewed forth by each speaker is exposed as a dislocated tributary, unable to pool into a communal conversation which could replenish their emotionally arid kingdom. The storm is awash with wasted words and it is not for nothing that Shakespeare personifies the source of the tempest as a human mouth.

In transposing King Lear to the London of the 1970s, I hoped to tap into the spirit of an age in which communication between a government and its populace was strained to breaking point. From rising unemployment to the random atrocities of the Irish Republicans, from trade union strikes to the three-day week, Britain in the 1970s became a country “as governable as Chile” in the populist view of one US politician. Inspired by the images of bin bags piled high in London’s Leicester Square during the ‘Winter of Discontent’, I sought to place Lear in a visual context where his shortcomings as a ruler were made abundantly clear, whilst also forcing him to haunt the fringes of the metaphorical scrapheap on which his daughters are so determined to discard him.

In her 2004 study of classical and Shakespearean tragedy, Mocked with Death, Emily Wilson suggests that the idea of ‘overliving’, living beyond the point where life has any value, is an experience common to many tragic heroes. King Lear, she argues, uses “parodic and perverted versions of the Resurrection to suggest the horrors of an unending life in the body” so that “excessive life is presented as a kind of living death”. On our dilapidated stage, choked with litter, Lear begins the play in a state of frustration and is soon propelled to exhaustion by his inability to communicate with those around him; this verbal stalemate is indeed a kind of “living death” or, to put it another way: When the feeling’s gone and you can’t go on, it’s tragedy (Bee Gees). ❚

SPS Film Competition

Elijah Patterson

Having made a whopping total of three short films before going into this year’s SPS Film Competition, I knew I wanted to give myself a bit more of a challenge and try something completely different to what I had done before. This meant I had to temporarily abandon my bizarre, nonsensical sense of humour, and instead embrace my bizarre, nonsensical sense of, well, something else. With this completely clear and coherent plan at the ready, I set forth again on a tumultuous voyage across the ocean of filmmaking towards… that metaphor really doesn’t make sense.

As I had learnt from my other short films, the best way to approach making a low-budget short film is to start with what you have access to and work backwards to create a story. This meant taking into consideration all my limitations (of which there are many), such as sourcing the actors, and finding locations, props and equipment I had access to, before coming up with the story idea. I thought about the most interesting and unique things that I had access to, and the first thing that came to mind was my uncle’s models, which he builds from scratch, so I knew I had to incorporate them into the story somehow. It was specifically the piece in the photo above, the small town on an island, that inspired the central idea to the story. There was so much detail in this model that made it feel as though it had a tragic backstory: the desaturated, dark brown that was used to paint the houses, the tiny, opaque windows, and the lone boat on the shore all created a strong sense of foreboding, of an abandoned village with a dark secret. The other main piece of inspiration I had was from the well-known piano piece (‘Gymnopedie No. 1’), which provided the right mournful, tragic atmosphere I wanted for the film.

With this inspiration, I then wrote a very brief draft of a story: a man goes into his house covered in blood, cleans off the blood, sits down and tries to paint a miniature werewolf, but gets interrupted by a bloody hand smacking his window. On paper, this story seemed rather uneventful, but I wanted to bring out the subliminal ideas and context through the cinematography and sound, rather than explicitly. This context was that the man was a werewolf, who had just transformed back into a man after involuntarily killing someone, and is struggling to come to terms with what he has done, using model making as a way of coping with his ‘condition’. At the end of the story, he is interrupted by the person he thinks he has killed hitting the window, therefore providing the opportunity for redemption. Whether or not this context was conveyed effectively enough in the short film is up for debate (I have had many comments that go along the lines of ‘amazing, what actually happened?’), but nonetheless, I believe a certain macabre atmosphere was created that kept one hooked. When I sent this story idea to my uncle, he was very enthusiastic about it, allowing me to use the model, his house, his camera and light. He even offered to act as the ‘model maker’, which was very convenient, as he had been method acting as a model maker for about two years preparing for this role. Having effectively killed all my birds with one stone, we set aside time on a Saturday evening, after my little cousin had gone to sleep, when we could film it. Unsure if this was going to be our only chance, we worked surprisingly efficiently, due in part to the fact that we had experience working together on his YouTube videos.

One of the main things I learnt from this process was to take other people’s advice, as they almost certainly have thought of things that you have not, and my uncle’s advice certainly contributed a great deal to certain shots in the short film. I think the short film, although far from perfect, really came together after editing and adding the music, provoking interesting feelings and ideas, even if it did not provide a coherent story. ❚

Party Time Review

Nik Boyd-Carpenter

2021-22 was an historic season for SPS Drama, as exemplified by the Spring production of Harold Pinter’s Party Time. A packed Milton Studio (including Lady Antonia Fraser, the wife of the late, great playwright and a celebrated author herself) was treated to a wonderful 45 minutes of dark comedy, with latent threat and social satire combining to great effect.

After the triumph of King Lear, it was no surprise that Mr Anthony turned to his favourite playwright, Harold Pinter, opting to stage Party Time – one of his later, shorter, and more political texts. The play depicts a genteel evening of upper-class platitudes and flattery, with typical Pinteresque comedy of menace. In the author’s own words, “the speech we hear is an indication of that which we don’t hear’” and this is especially true of Party Time. Throughout the play the subtext threatens to overwhelm the actual dialogue as eight guests at a dinner party wade through the evening, carefully navigating oblique references to ‘the street’ and ‘soldiers’, all the while ignoring Dusty’s panicked questions about the whereabouts of her brother Jimmy. However, as the production’s clever use of sound and lighting between scenes revealed, all is not well; the party guests are members of the privileged elite of a repressive autocracy, but the cries of dissent from outside get louder and louder as the play progresses. In a stunning culmination, Jimmy finally appears, his bewildering monologue a bitter depiction of injustice and abuse of power.

Acting in a Pinter play requires a particularly sophisticated understanding of language and subtext, and the cast of Sixth Form and Lower Eighth actors more than rose to the occasion. Julien Abbosh was an excellent Terry, caught between being an anxious flatterer and pugnacious husband, creating moments of wonderful comedy. Evan Burks was similarly impressive, oozing sleek, bureaucratic brutality in his role as Gavin, the party’s oleaginous host. Will Freebairn excelled as Douglas, a caricature of self-satisfied propriety, and his comic dialogues with Fred (Yusuf Baig) were particularly funny. Yusuf’s performance as Fred was just as compelling, and his conversations with Charlotte brilliantly brought to life the ambiguity that is so typical of Pinter’s work. In a post-COVID first, the play featured actors from SPGS, each of whom performed with verve. Ondine Gregory and Natasha Sweeting were fantastic as Charlotte and Liz ➦

respectively, bringing great humour to their interchanges. As Dusty, Alexa O’Leary successfully presented a character of great complexity, simultaneously acting the victim of authoritarian oppression and using comic wit as a tool for female resistance in the face of male dominance. However, special praise must go to Hebe Legge in the role of Melissa. Acting a character many years older than she was, Hebe showed fantastic control of tone and facial expression to capture her character’s haughty affectation, but also her underlying insecurity. It was an outstanding performance. Finally, Enyu Hu, fresh from victory in the SPS Monologues Competition, was deeply unsettling in his masterful delivery of Jimmy’s speech at the close.

The production benefited greatly from its lighting, sound, costume, and set. Comfortable armchairs, smart suits and dresses and a soft yellow wash all helped create the impression of a comfortable living room, only for the back door to swing open at the close to reveal a bruised Jimmy in tattered rags, shattering the illusion of peaceful control. Similarly, the juxtaposition between the interludes of dancing, to a variety of Broadway jazz standards, and the use of recordings of public disorder and unrest, emphasised the latent violence lurking behind the party’s icy decorum. The contrast between the party’s lighting and the eerie purple used in between scenes also accentuated the sense of threat to good effect.

In all, the play was a truly impactful performance; the ensemble cast worked brilliantly to bring out moments of genuine comedy throughout, more than earning the right to enjoy some famed ‘Pinter pauses’ while keeping the audience engaged throughout. There was certainly an additional immediacy to the play given its context. Watching, in March 2022, just weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine, a play in which the ruling class blinds itself to the violence that sustains it felt extremely timely. It also points to the relevance of live theatre to both illuminate and provide solace from our world – having lost this privilege during the pandemic, Party Time was an excellent reminder of why we need it so much. ❚

Talk Show: Review

Marco Sicheri

As the audience took their places around the Milton Studio, the lights began to dim and concentrate on the production ahead. Upstage was a creaking window, rimmed in sleazy aquamarine light and set high on a dirty wall, with its paint peeling and beer stains scattered across its surface. A ragged desk lay in the middle of the studio, in front of an ageing swivel chair. These two pieces of furniture would prove pivotal in explaining the development of the protagonist Sam. Across the carpet, litter was dispersed, suggesting disorganisation and a lack of cohesion, which was soon revealed to be symbolic of the family dynamic within the household. Mr Chamberlain, the director, had made the decision to present this play in a thrust arrangement, with the audience on three sides; this increased engagement, giving the production the same sense of immersion as a film.

Talk Show is a play about the complete breakdown of communication within a family, a family torn apart by grief, loss, and a lack of hope for the future. Sam is desperate to find a way to express himself and, alone in his father’s basement, he turns to the American talk show format to fill the void within himself. However, the chaos of his uncle Jonah’s return forces the family to confront their grievances and attempt to move on from the past. The play also depicts the story of three generations of men, all of them struggling to survive financially, emotionally, and existentially. The more they need each other, the more they drift apart. Through pride and stubbornness, they barely keep their heads above the water.

Sam (Rufus Goodman) holds onto his talk show as if it is a lifeboat. Jonah (played with raw recklessness by Felix May) has faced the worst anyone can face and struggles to connect. Bill (Paddy Barry), working class and out of work, refuses to acknowledge this brave new world might not have a place for him. Ron (Enyu Hu), wearing a vintage shirt and old enough to know that hardly anything makes sense, calmly focuses everyone’s thoughts on what’s important and true. The play’s energy seems effortless, with subtext swimming in and out of view. The humour, often very funny, oozes desperation. Interesting theatrical devices add to the tension (the baby monitor for overhearing and mishearing conversations), and playfulness comes in unexpected forms, such as the use of the snake when Steve is presented (Theo Westcott). In addition, Daryl’s lack of desire to interact and enjoy the talk show (played by Liam Metcalf) allowed for a great scene scattered with crude humour. ➦

Light and sound in this production were used to their fullest potential, bringing to life the relentless energy and discombobulation of the household. This was most effectively portrayed in the scene in which Jonah enters, with a stark and sinister shift in lighting levels, providing a glimpse into the dynamic of the characters and personalities that would soon emerge. The lighting director, Ben Swartzentruber, controlled the atmosphere of each scene superbly, manipulating the tone and focus of the lights in order to guide the audience’s attention. Moreover, the use of sound effects in transitions and in the scenes where the talk show is live, allowed us to get a real sense of the context of the story and the effort Sam went through in order to present his show and keep it on air, even in the face of dire financial constraints. Finally, the whole cast must be applauded for their ability to adapt to the difficult circumstances (including a much-disrupted rehearsal schedule) brought on by COVID. Throughout the play, all the actors showed immense interest in their specific characters, leaving the audience spellbound. The controversial ending of Jonah’s arrest, with his father (and ultimately Jonah himself) believing time to reflect in prison would help him to heal, was an emphatic full stop to an incisive and highly entertaining piece of theatre, highlighting the themes of family unity and generational responsibility that ran through the production. ❚

The Rivals

Julien Abbosh

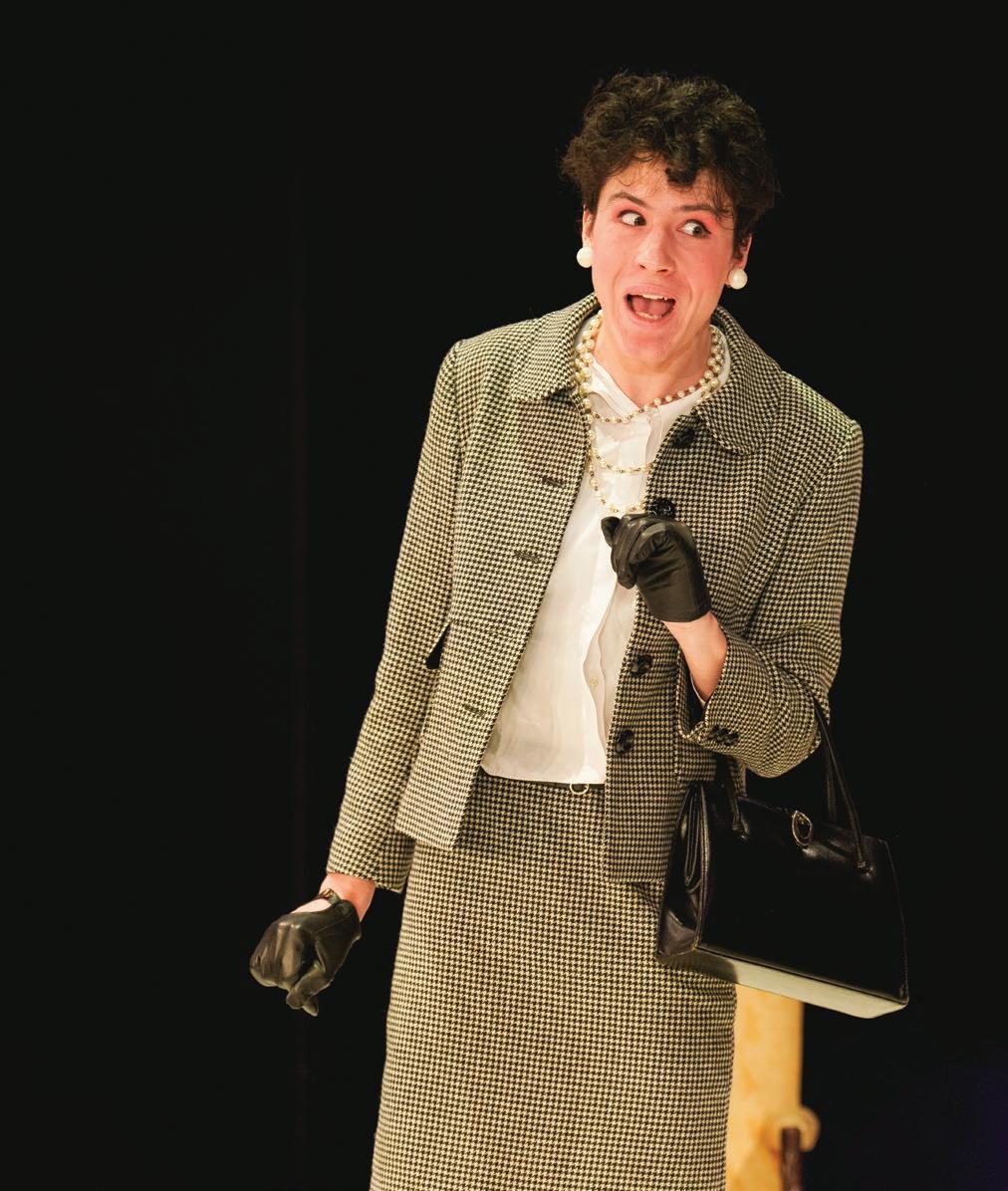

As people gradually filled the Pepys Theatre, attention was immediately drawn to the grand and imposing set design: the stage was painted in a circular pattern of bright white and red, with a grey signpost centrepiece pointing in three directions. Upstage, four Colosseum-like columns stood; once the play began, these came to life, changing colours during transitions and adding to the energetic atmosphere. Mr Dormandy, the director, in his in-person debut in the Pepys Theatre made the decision to transport The Rivals – a classic comedy first performed in 1775 – to 1967 (the ‘Summer of Love’), and accompany it with all-time great songs from The Beatles, The Kinks and The Animals.

Dormandy’s Rivals is a play that tells the story of a young American soldier, Jack Absolute (Harry Hickles), stationed in England, whose romantic interests and ties are the central cause of strife and stress between all the characters. Communication completely breaks down and only Jack seems to (just about!) know what is going on. As the house lights first dimmed and the stage lights flashed on, we were introduced to the vibrant characters we would see throughout the play: the cast trickled on and off the stage, rushing from corner to corner, and the comedic tone became immediately apparent. Noticeably, the elderly Thomas’s (Benedict Harrison) distinct and hilarious hobble on and off the stage immediately engaged the audience. The excitement caused by the high energy was obvious; one could feel the audience on the edge of their seats anticipating scene after scene. We really wanted to see each character’s story play out and reach the resolution of the tension.

Mrs. Malaprop (William Shackleton) attempts to direct the love between Jack and Lydia (Jasmine Bakhshi) and inadvertently becomes amorously involved with Jack’s father, Senator Absolute (Leo Odgers). This explosive combination of high-intensity, pretentious and overbearing Mrs. Malaprop with a traditional, short-fused Senator was a root of pure comedy throughout the play. Faulkland (Lysander Kahane) is a lovesick and ➦

paranoid young man, who is in almost disbelief about his engagement to Julia Melville (Ayoka Lawani), and we get a glimpse into his tumultuous mind when he questions if their love is genuine. Further comedy and dramatic irony were brought through the fighthungry and argumentative Sir Lucius O’Trigger (Elijah Patterson), whose actions threatened conflict between Jack and Bob Acres (Rufus Goodman). In contrast to Jack’s suave and secure aura, Bob is a somewhat naive and timid countryman with an impressionable personality. The Rivals was an extraordinary visual play due to the extent to which the actors understood their character’s physicality and were able to demonstrate it to the audience: David (Felix May), Fig (Ryan Davey) and Lucy (Eleanor Grant) all pushed their respective characters to their fullest comedic extent.

Light and sound truly enriched the production, adding colourful energy and highlighting themes of the ‘Summer of Love’. The multi-coloured lighting was present throughout, always illustrating the high emotions and comedy. Suleyman Ansari, the lighting director, made sure all the lighting was smooth and perfectly timed, often adding to a line by adjusting the lights with comedic finesse. Harry Rimmer also executed the sound perfectly, complementing scenes with music that mirrored the emotions. Thanks to all the stage crew, transitions were incredibly smooth, allowing the play to take place in many different sets. The Rivals received fantastic praise from all who attended; the High Master commented as follows: “It was a sheer joy to watch The Rivals and I was delighted to be able to bring Oliver Snowball, the next Head of the Junior School and a drama specialist, as my guest. We both felt that the performances would not have been out of place on a professional stage and the Shackleton / Odgers double act, in particular, was something remarkable. The Snowball family also met many of the cast afterwards and were struck by their humility and

desire to give credit to the whole team. I did bag a signed poster though in preparation for the Olivier Awards in the future so that I can say that I saw them on the Pepys stage first!”

Finally, everyone must be praised for their commitment and desire to make The Rivals into such an incredible experience for all that came to see it. Despite challenges from the pandemic, and both the Upper Eighth and Sixth Forms facing distracting uncertainty about their mock exams, the cast came together to produce something fantastic. ❚ This explosive combination of high-intensity, pretentious and overbearing Mrs Malaprop with a traditional, short-fused Senator was a root of pure comedy throughout the play.

The Hog: Review

Leo Odgers

William Shakespeare, Harold Pinter, Richard Sheridan – Elijah Patterson. These are not only the names of the playwrights who have penned the shows performed by SPS Drama this year but also four masters of their craft who defined the theatre of their respective times. For Shakespeare, it was the Elizabethan period, for Sheridan the Georgian, Pinter the post-war era and for Elijah Patterson: the A Level Politics syllabus of Summer 2022. Though written nearly a year ago, The Hog – the tale of a once popular megalomaniac desperately trying to hold on to power by any means as he rapidly falls out of favour with the public – found itself deeply pertinent, almost prophetic, by the time it premièred in late May. However, this dictator or ‘Great Leader’, played expertly by Harry Hickles, chooses to distract the public from his sins not with convenient trips to Kyiv or historic Jubilees but with a giant, genetically engineered pig monster.

Indeed, the plot of ‘The Hog’ is admittedly a bit bloody bonkers, with progressively more emphasis on the bloody. The play opens in media res, or ‘in the middle of the action’ (for readers who have no knowledge of smug A Level Drama terminology). The Great Leader has been shot by a disgruntled rebel in the street and is tended as he retreats, bleeding, to his fortified Palace by his chief General –excellently portrayed with a convincing

reticence by Julien Abbosh. Whilst the Leader hastily wraps a bandage around his open bullet wound, his regime begins to rapidly unravel. Wishing to quell the uprising, he orders the creation of a rapacious sewer dwelling ‘Hog’ which crushes and devours dissidents, inspired by an urban myth which has spread throughout his realm. However, as the Great Leader’s desperation and paranoia intensifies, so too does the resistance of his subordinates – the exasperated General and the lowranking Private Adams, a quiet schemer played with sinister subtlety by Yusuf Baig. As the Leader becomes more and more unhinged, soon trying to poison his own General, it is Baig’s Private who eventually topples the dictator, leaving the Great Leader with the morbid choice of shooting himself or being mauled by the rabid Hog.

Yet the story maintains a weight and tension, sustained unrelentingly by the virtuoso writing and direction of Elijah Patterson. His script paints a recognisably crumbling establishment held together only by fear and residual loyalty. Patterson perfectly captures the neurosis of an autocratic state with Pinter-esque subtext and correspondingly macabre humour. At one point Hickles asks Baig ‘Am I a good leader?’ to which Baig’s Private responds, after squirming timorously in his seat, ‘You are a great leader, Great Leader.’ The response elicits a laugh from the audience but also speaks more profoundly to many autocracies which are tenuously consolidated by conditioned rhetoric rather than genuine enduring popularity. The use of set in The Hog was minimal but effective. The stage consisted of a central mahogany desk, two leather chairs and door upstage. There was little suggestion of the wider palace it is presumably situated in. As in many dictatorships, greatness is assumed but not proven. The music was similarly sparse but nonetheless powerful. The story was punctuated by unsettlingly discordant instrumentals including a despondent track from Donnie Darko, the teetering piano of Radiohead’s “Deck’s Dark” (my personal favourite) and the dusky trudging guitar chords of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt” which scored the Great Leader’s quiet contemplation of his uncertain future while lit in a suitably liminal dim green glow. The absence of familiar words in these recognisable instrumentals supported the sense of a void at the heart of the Leader’s regime and made it clear that his days in power were numbered. The audience was only left to speculate who shall inherit his empire of dirt. The play closed to Vera Lynn’s “We’ll Meet Again” which at once recalled wartime propaganda and suggested an eternal inevitability in the rise and fall of despotic regimes. We have met men like the Great Leader again and again throughout history and, though he is ultimately toppled, the cycle seems destined to continue as the Private assuredly seizes his tyrannical mantle. ❚

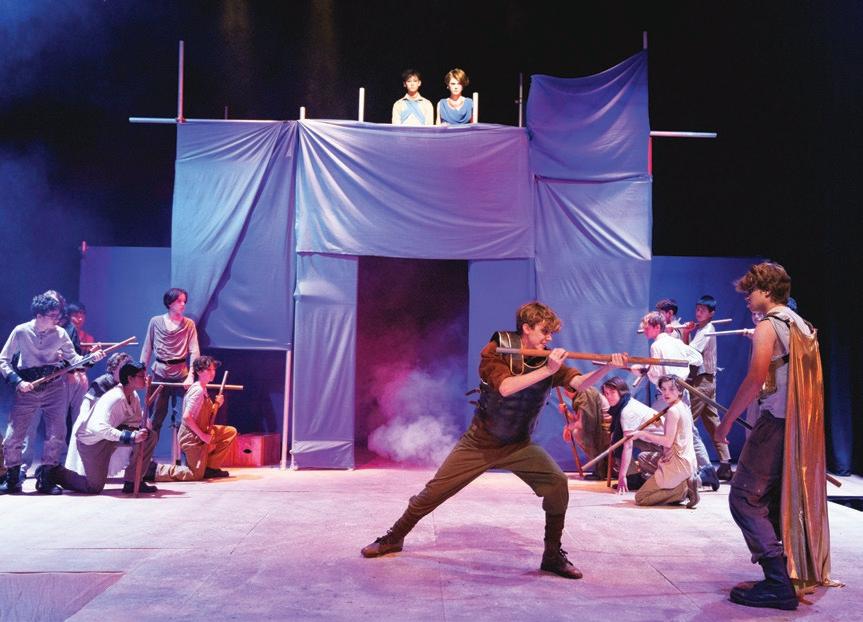

The Last Days Of Troy Review

Eli Joseph

The play is adapted from Homer’s Iliad as well as other epics from the Epic Cycle, taking you through the final year of the brutal war which ensued after Paris famously stole Helen from the Greeks. We see the frail Greek camp at the start, broken and battered, after the awful plague sent from the Gods.

Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks, learns the nature of the plague and realises the only way to get rid of it is to return the daughter of a priest that he took after battle. In his anger, though, Agamemnon demands Achilles’ own slave girl as compensation. Achilles, furious, refuses to fight for the Greeks in response, which derails the Greek army further. The Greek commander Odysseus decides to go down another route, and convinces Patroclus to pretend to be his best friend Achilles, and rally the Greek army into battle. But Patroclus is struck down by Trojan prince Hector, which enrages Achilles. Achilles re-enters the war, turning the tides once more. The famous coup de grace comes when Agamemnon sends a fake horse into Troy as a gift with Greek soldiers hidden inside. This eventually leads to a gruelling victory for the Greek army and the desecration of Troy.

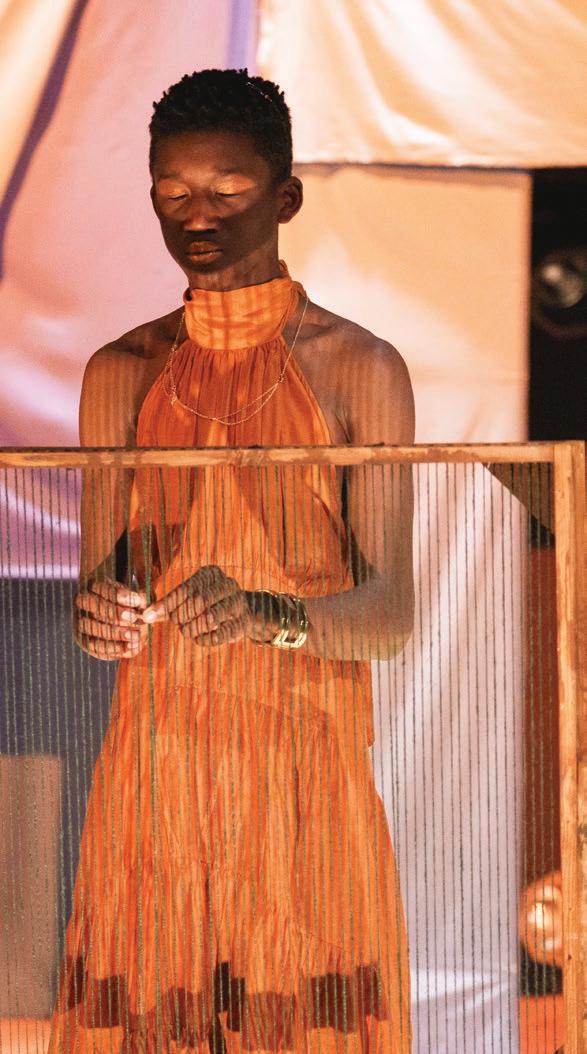

After a year of studying different stage types for GCSE drama, I am able to give an “educated” debrief on the exceptional set, costume, and lighting used during the production. The stage was split into three levels, allowing for both the gods to look down on the battle and feed their thoughts to the audience, and for the audience to be immersed in the intense discussions taking place between the generals and warriors. The chorus had a mixture of remarkable costumes, but the stand-out must go to Elijah Hountondji’s magnificent flowy dark orange dress while playing the role of Helen. The entrance of Fred Websper as Paris surely woke up any dozy audience

members, as the piercing white light emphasised the introduction of the incredible Trojan prince – Paris.

The hard work put in by the entire cast shone throughout the play, but I couldn’t write this report without mentioning some of the brilliant individual performances across the three nights. Nico Groeller and Max Swinnerton starred in the roles of Zeus and Hera, observers and commentators on the war. Max totally embraced his role as Hera, and Nico conveyed the wisdom of Zeus in an affecting manner. The emotion of the story was captured and delivered powerfully, in a mesmerising monologue from Alex Toledano as Sinon. Jasper and Austin also treated us to an epic fight scene between Patroclus and Achilles, which surprised us all, and possibly had the audience worried for a second about Jasper’s safety! Theo Frankel excellently portrayed the elegance of his character in Andromache, and Henry Smith played the general Odysseus superbly, even taking it to the lengths of roping down onto stage from the ceiling! Fred Websper had a truly memorable entrance as Paris and alongside Sam Steeden as Hector, they both played the Trojan brothers to near perfection.

All in all, it was a fabulous production and a true joy to watch. I’m sure the cast pay great thanks to Mr Pirrie and Miss Evans for their tireless work in directing the project. It was a truly superb evening and I could not think of a better way to end a brilliant year of SPS drama, after it was sorely missed during the COVID years. ❚