16 minute read

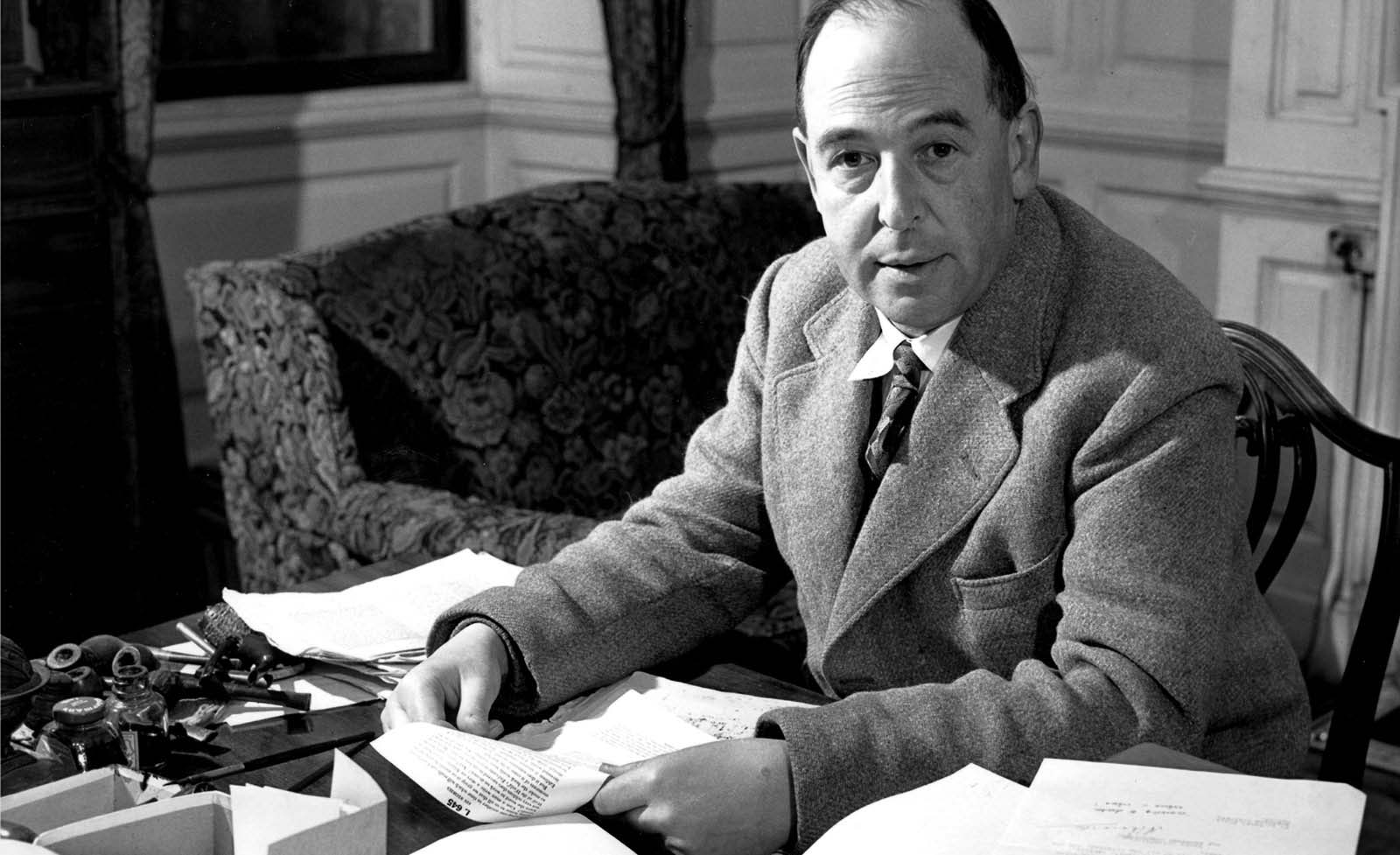

How C. S. Lewis Helped Lead Me to Lutheranism

Gene Edward Veith

When I was a teenager, I was big fan of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. One of the blurbs on the back of my Ballantine edition of the trilogy expressed how the fantasy novels made me feel: “here are beauties that pierce like swords or burn like cold iron.” We lived in a small town in Oklahoma, but occasionally my parents would drive us all to Tulsa, the big city, and when we did, we would go to a bookstore. Randomly browsing the shelves on one visit, I saw a name that I recognized: C. S. Lewis. He was the one who wrote the line about beauties that pierce like swords and burn like cold iron!1 I opened the book and saw that it was dedicated to J. R. R. Tolkien! I had to buy that book, so, using the money I earned from my job at the Dairy Queen, I bought Screwtape Letters. After reading Lewis’s preface, I remember marveling, “He really believes in the devil!” I found the novel itself, with its combination of satirical humor and ironic spiritual counsel, entrancing. I was raised in a mainline liberal Protestant denomination and had never heard anything like this. “Here is someone,” I thought, “who takes all of that old stuff in Christianity seriously.”

Mere Christianity

I had to read more. I next bought Mere Christianity. This one blew me away. My church had no creeds and let us believe whatever we wanted, though I was aware of Jesus and the Bible. But Lewis was showing me actual theology. When I got to the part in the book about the Incarnation, I was thunderstruck. Jesus is God? God became a human being! I had never even heard that before. This struck me as beyond wonderful, giving me a completely different way of thinking about God— not as an abstraction looking down on us from up above, but as a real person who came down from heaven to become one of us.

I was so stimulated by what I was learning from Lewis about the Incarnation that I wanted to talk to one of our ministers about it. I shared my excitement with a youth minister, fresh out of seminary. “Well,” he told me, “we don’t really stress that anymore.”

Deflated, I began to look elsewhere. Lewis said that he was simply writing about “mere Christianity,” the beliefs common to all Christians from all denominations. But I found mere Christianity hard to find. I saw traces in my Baptist friends, but they didn’t have much theology. I could see some of it in the Catholic church, but it was the 1960s and the services I visited and the priests I talked to were caught up in post-Vatican II modernism.

How the Anglican Lewis Led Me to Luther

I kept reading Lewis and then the books that he read that were instrumental in his coming to faith. I learned more and more, but books alone are no substitute for a church.

I went off to college, got married, went to grad school. Having exhausted my C. S. Lewis-inspired reading list, I finally read the Bible, which had a big impact. We started hanging out with campus evangelicals, though we still attended that same mainline Protestant church.

I wrote my dissertation about the 17th century Christian poet George Herbert, focusing on how he was influenced by the Reformation. This had me reading the Anglican Reformers, Puritans, Calvin, and my personal favorite Luther.

My first academic job took us back to small town Oklahoma. My wife and I resolved to find a church that believed in the Bible and in the Gospel, so we started church-shopping. We visited a Lutheran congregation, where we were overwhelmed with the liturgy—“It’s like stepping back into the Middle Ages,” my wife said, which for us was a good thing—and I was amazed to see that the church still taught what I had been studying in my dissertation. We took the adult instruction class and became Lutherans. Since then, I have been going deeper and deeper into the Lutheran tradition, which I have found unutterably satisfying. Though many factors and life experiences brought us to Lutheranism, I credit C. S. Lewis with starting me on my way. Lewis was not a Lutheran. Anglicans, even conservative ones like Lewis, are characterized by doctrinal latitude, their main point of unity being liturgical worship according to the Book of Common Prayer. I can now see clearly where Lewis falls short according to Lutheran confessional standards. And yet, Lewis is often helpful to a Lutheran perspective anyway.

For example, Lewis is weak on the Atonement. He writes,

“The central Christian belief is that Christ’s death has somehow put us right with God and given us a fresh start. Theories as to how it did this are another matter. . . . Theories about Christ’s death are not Christianity: they are explanations about how it works. Christians would not all agree as to how important these theories are. My own church—the Church of England does not lay down any one of them as the right one. The Church of Rome goes a bit further. But I think they will all agree that the thing itself is infinitely more important than any explanations that theologians have produced.”2

True enough, perhaps, but we Lutherans would agree that the “theory” is quite important. Nevertheless, it was Lewis who made me grasp the doctrine of the Substitutionary Atonement. In The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Aslan substitutes himself for the rotten sinner Edmund, whom we readers have been made to despise, dying in his place in order to save him.3 I still remember the exhilaration I felt when I read that, seeing myself in Edmund and realizing what it meant for the Incarnate Son of God to die for me.

Lewis on the Biblical Critics

Lewis was weak on the Bible. He did not believe in the inerrancy of Scripture.4 And yet, he wrote one of the most devastating critiques of the historical-critical approach to the Bible in his essay “Fern Seeds and Elephants,”5 in which he writes:

“The undermining of the old orthodoxy has been mainly the work of divines engaged in New Testament criticism. The authority of experts in that discipline is the authority in deference to whom we are asked to give up a huge mass of beliefs shared in common by the early Church, the Fathers, the Middle Ages, the reformers, and even the nineteenth century. I want to explain what it is that makes me skeptical about this authority. . . . First then, whatever these men may be as Biblical critics, I distrust them as critics. They seem to me to lack literary judgment, to be imperceptive about the very quality of the texts they are reading. . . .I have been reading poems, romances, vision-literature, legends, myths all my life. I know what they are like. I know that not one of them is like this. Of this text there are only two possible views. Either this is reportage. . .Or else, some unknown writer in the second century, without known predecessors or successors, suddenly anticipated the whole technique of modern, novelistic, realistic narrative.. . . [Second], all theology of the liberal type involves at some point—and often involves throughout—the claim that the real behaviour and purpose and teaching of Christ came very rapidly to be misunderstood and misrepresented by His followers, and has been recovered or exhumed only by modern scholars. . . .The idea that any man or writer should be opaque to those who lived in the same culture, spoke the same language, shared the same habitual imagery and unconscious assumptions, and yet be transparent to those who have none of those advantages, is in my opinion preposterous. . . .Thirdly, I find in these theologians a constant use of the principle that the miraculous does not occur.”

Finally, after supporting these objections, Lewis calls out the sheer speculation that characterizes so much of modern Bible scholarship, pointing out that he knows from first-hand experience that the critics who have confidently reconstructed the origins and sources of his writings have all been wrong! So how can we trust the source critics who are working with texts written nearly two thousand years ago?

Purgatory

There are other areas in which Lewis fell short of Lutheran orthodoxy. For example, Lewis believed in purgatory.

There are other areas in which Lewis fell short of Lutheran orthodoxy. For example, Lewis believed in purgatory. While admitting that the Reformers were right to cast doubt on “’the Romish doctrine concerning Purgatory’ as that Romish doctrine had then become,” he writes,

“Our souls demand Purgatory, don’t they? Would it not break the heart if God said to us, ‘It is true, my son, that your breath smells and your rags drip with mud and slime, but we are charitable here and no one will upbraid you with these things, nor draw away from you. Enter into joy’? Should we not reply, ‘With submission, sir, and if there is no objection, I’d rather be cleaned first.’”6

Well, purgatory was never described like a bracing shower, but as centuries of torment. The “Romish doctrine” from Dante through today has always been that God requires temporal punishment even for sins that have been forgiven. And yet, strangely, this punishment can be cancelled, not by the atonement of Christ but by indulgences, prayers for the dead, and the intercession of the saints. Here Lewis is making up his own belief. If he is not being Protestant, he is not being Catholic either.

Distinction of Law and Gospel

Nevertheless, Lewis’s writing also includes elements that are usually associated only with Lutherans. In Mere Christianity, he elegantly applies the distinction between Law and Gospel. After writing extensively about the objective reality of the moral law, in his Book I: “Right and Wrong as a Clue to the Meaning of the Universe,” Lewis ends that section with a chapter entitled “We Have Cause to be Uneasy.”

“Christianity simply does not make sense until you have faced the sort of facts I have been describing. Christianity tells people to repent and promises them forgiveness. It therefore has nothing (as far as I know) to say to people who do not know they have done anything to repent of and who do not feel that they need any forgiveness. It is after you have realized that there is a real Moral Law, and a Power behind the law, and that you have broken that law and put yourself wrong with that Power— it is after all this, and not a moment sooner, that Christianity begins to talk. When you know you are sick, you will listen to the doctor. When you have realized that our position is nearly desperate you will begin to understand what the Christians are talking about. . . .They tell you how the demands of this law, which you and I cannot meet, have been met on our behalf, how God Himself becomes a man to save man from the disapproval of God.”7

It is after you have realized that there is a real Moral Law, and a Power behind the law, and that you have broken that law and put yourself wrong with that Power—it is after all this, and not a moment sooner, that Christianity begins to talk.

Having first set up his readers with the reality of the Law and shown that they have not kept it, Lewis then moves into Book II: “What Christians Believe.”

Lewis Held to Many Tenets of Lutheran Theology

Unlike most Protestants but like all Lutherans, Lewis has a high view of the Sacraments. I remember being caught short in my pre-Lutheran days when I read, “Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbor is the holiest object presented to your senses.”8 Here is Luther’s neighbor-centered ethic, but I didn’t realize that. What struck me is that “the Blessed Sacrament. . .is the holiest object presented to your senses.” I wondered, how can that be? Now that I am a Lutheran, I know. As Lewis said,

“I do not know and can’t imagine what the disciples understood Our Lord to mean when, His body still unbroken and His blood unshed, He handed them the bread and wine, saying they were His body and blood. . . .Yet I find no difficulty in believing that the veil between the worlds, nowhere else (for me) so opaque to the intellect, is nowhere else so thin and permeable to divine operation. Here a hand from the hidden country touches not only my soul but my body.”9

Lewis also understands vocation in Luther’s sense, not just as a “job,” much less as a “work ethic,” but as a sphere in which God has placed us for service. “A sacred calling is not limited to ecclesiastical functions. The man who is weeding a field of turnips is also serving God,” he wrote. ““The great thing is to be found at one’s post as a child of God.”10

Lewis also expresses the Lutheran theology of worship as having to do with the reception of God’s gifts:

“It is in the process of being worshipped that God communicates His presence to men. . . Even in Judaism the essence of the sacrifice was not really that men gave bulls and goats to God, but that by their so doing God gave Himself to men; in the central act of our own worship of course this is far clearer—there it is manifestly, even physically, God who gives and we who receive.”11

Lewis never, as far as I have been able to find, has published a bad word about Luther. He praises Luther’s “geniality,” especially over against his nemesis Thomas More, who usually gets the better press:

“When we turn from the religious works of More to Luther’s Table Talk we are at once struck by the geniality of the latter. If Luther is right, we have waked from nightmare into sunshine: if he is wrong, we have entered into a fools’ paradise. The burden of his charge against the Catholics is that they have needlessly tormented us with scruples.”12

It’s All about the Gospel

As a literary historian, his primary occupation, Lewis sets the record straight about the Reformation, dispelling the misconceptions about the Reformers and the “Puritans.” “Whatever they were, they were not sour, gloomy, or severe; nor did their enemies bring any such charge against them,” he writes. “Luther, [More] said, had made converts precisely because ‘he spiced al the poison’ with ‘libertee’ (ibid. III. vii). Protestantism was not too grim, but too glad, to be true.” The Catholic side was all about Law; the Reformers, especially the early ones such as Luther, were all about the Gospel:

“In the mind of a Tyndale or Luther, as in the mind of St. Paul himself, this theology was by no means an intellectual construction made in the interests of speculative thought. It springs directly out of a highly specialized religious experience. . . .The man who has passed through it feels like one who has waked from nightmare into ecstasy. Like an accepted lover, he feels that he has done nothing, and never could have done anything, to deserve such astonishing happiness. . . . All the initiative has been on God’s side; all has been free, unbounded grace. And all will continue to be free, unbounded grace. His own puny and ridiculous efforts would be as helpless to retain the joy as they would have been to achieve it in the first place. Fortunately they need not. Bliss is not for sale, cannot be earned. ‘Works’ have no ‘merit,’ though of course faith, inevitably, even unconsciously, flows out into works of love at once. He is not saved because he does works of love; he does works of love because he is saved. It is faith alone that has saved him: faith bestowed by sheer gift. From this buoyant humility, this farewell to the self with all its good resolutions, anxiety, scruples, and motive- scratchings, all the Protestant doctrines originally sprang.”13

Conclusion

Though C. S. Lewis was not a Lutheran, he was very instrumental in making a Lutheran of me. Though confessional Lutheranism is not “ecumenical,” as he tried to be, in confessional Lutheranism I finally found “mere Christianity,” a theology that embraces the whole scope and range of Christianity, being sacramental and liturgical like the Catholics, while also being Biblical and evangelical like the Protestants. Only a rigorous theology can hold such poles together. Lewis nourished a yearning in me for what I have found in Lutheran spirituality: Truths “that pierce like swords” and “burn like cold iron.”

Gene Edward Veith is a retired English professor and college administrator, most recently at Patrick Henry College and Concordia University Wisconsin. He has written or edited 30 books, including The Spirituality of the Cross, God at Work, and Embracing Your Lutheran Identity. He has a Ph.D. from the University of Kansas. He and his wife live in St. Louis.

Though C. S. Lewis was not a Lutheran, he was very instrumental in making a Lutheran of me.

Endnotes:

1. The line is from Lewis’s review of Lord of the Rings collected in On Stories and Other Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1982), 84.

2. C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 57.

3. C. S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (New York: Macmillan, 1970), 146-160.

4. See, for example, C. S. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1958), 109-119.

5. Collected in Christian Reflections, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: Harper Collins, 1981), 191208.

6. C.S. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm: Chiefly on Prayer (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1963), 108-109.

7. Lewis, Mere Christianity, 38-39.

8. C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1965), 15.

9. Lewis, Letters to Malcolm, 103.

10. Lewis, “Cross-Examination,” in God in the Dock, ed. Walter Hooper (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2014), 264, 266.

11. Lewis, Reflections on the Psalms, 93.

12. “Donne and Love Poetry,” in C. S. Lewis, Selected Literary Essays, ed. Walter Hooper (New York: Harper Collins, 1961), pp. 116-117.

13. C. S. Lewis, English Literature in the Sixteenth Century Excluding Drama (London: Oxford University Press, 1954), 33-34.