16 minute read

THE BOUND WILL IN TEXAS: A MINORITY GUEST AT A FRIENDLY LUNCHEON OF THE FREE WILL SOCIETY

Paul Owens

Not long ago at the gym, my friend Joel asked me a rare question. His dad was a Methodist pastor, and Joel now attends a local Baptist Church. Joel asked me - in a calm, matter-of-fact way - “so do you believe in free will?” I thanked him and congratulated him for getting to the heart of the matter. He had asked a question that most of my beloved neighbors lack the presence of mind to put directly into words. We all want desperately to claim some imagined power for our own will, but how often do we consciously pose the crux of our own desire to one another, let alone voice our prideful claim directly to the Lord in prayer? Luther commended his opponent Erasmus for also uniquely getting to the heart of the matter. “You and you alone have seen the hinge on which everything turns and have gone for the jugular.”1

The myth of human free will is practically in the drinking water in America, and even in the Church, so much so that you may be reading this right now and saying to yourself “why is he calling it a myth?” The jugular, as Luther and Erasmus both knew, is trust in God versus trust in man’s own abilities. My conviction is that the human will is bound to trust in itself, bound to do what it wants to do… enthralled with itself. Just give your will or mine half a second and you’ll see. Freedom only breaks in for us when our will gets crucified with Christ, that is, when you come to the end of yourself - which you and I both hate to do –and realize that your conscience is hobbled, bound to yourself… unrighteous… wrong… and that only Christ crucified gives himself as righteousness for the unrighteous, namely for you. Then and only then, we have all the free will we could ever want or need: our dear heavenly Father’s will for us, rather than our own. As Paul confesses, “I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me. And the life I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20).2

Then and only then, we have all the free will we could ever want or need: our dear heavenly Father’s will for us, rather than our own.

God bless my friend Joel for his amiable, calm manner when he went straight for the jugular at the gym that day. Too often the devil lures us in and convinces us that the debate around this question is about winning a theological argument. For Luther, and I hope for me and the people I serve, it’s about something much deeper and profoundly more helpful to sinners who struggle under the Accuser’s constant attack. It is about rescue from that attack and from the blackhole of oneself. It’s about handing over life to those who otherwise have no life in them (John 6), about freeing a burdened, bound conscience from itself. Gerhard Forde has said as much in his slim-but-significant book, The Captivation of the Will. Forde writes that Luther’s response to Erasmus’ diatribe on free choice, De libero Arbitrio, "should not be seen primarily as a negative work or merely one more theological debate, but as a desperate call to get the gospel preached. It is intended to be a summons for us, not a dirge. A conversation to be entered full of humor and theological gusto.”3 Even Erasmus himself, a vehement opponent of Luther’s at times, lauded his consistent gospel-filled message. A few years after the exchange with Luther, Erasmus wrote “the theologians curse Luther, and in cursing him curse the truth delivered by Christ to the apostles… Luther’s books were burnt when they ought to have been read and studied by serious persons.”4

The Natural Will, Clint Eastwood, and the Holy Spirit

Oswald Beyer writes, “People by nature have their own natural idea of God, in which they flatten everything out to make it fit their concept of the One, the True, the Beautiful, and the Good.”5 This self-justifying thinking is the natural way of the human heart, and this “thinking and striving of the heart is radically evil” (Genesis 6.5; 8.21). My heart and yours has busy fingers that are always trying to make something of their own rather than live by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God. And what the heart makes is counterfeit… good looking, good sounding, sense-making idol after idol.

Before Satan enters to peddle the voice of your free choice as a counterfeit to the Lord’s free will and his voice (Genesis 3), men and women are content to "live by every word that comes from the mouth of God" (Deut. 8.3, Psalm 40.3, Psalm 71.8, Psalm 89.1, Proverbs 13.3;18.7, Isaiah 53.7), etc. But then, as soon as Satan whispers into our ears, we begin to take our words over God's word and talk of our will emerges and our free choice is then asserted. “As Erasmus saw it, it is essential that man should have freedom of choice. Without it there would be no sense in meting out praise or blame, since there could be no possibility of man’s meriting either” (LW 33.9).

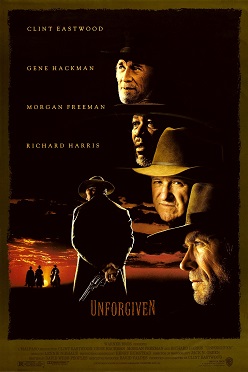

God’s will is justification by grace through faith; our will is self-justification by choice. The human will is so fast bound to itself and its own words that it can do no other than to insist on an economy of deserving: “I must have the freedom to choose or refuse grace, otherwise how will the bad and the good each get what they deserve?” When the self seeks to justify itself in this way, bringing an imagined righteous choice of its own, a dose of reality from the famous theologian Clint Eastwood can be most helpful. In the 1992 film Unforgiven, his character Will Munny reminds us: “deserve has got nothing to do with it.”6

The notion of free will is a trick of Satan –perhaps his best – in order to deceive you and me into trusting ourselves and our own words. The popular, attractive, easy-to-swallow proposition that “my will is free” ultimately ends in burden,

sin, and death. Christ alone is freedom, forgiveness and life for you and for me. To pull the curtain back on this wizard’s deception, the law of God stops our mouths’ insistence on free choice and holds this will, which is enamored with itself, accountable to God. It isn’t just the addict’s will that is bound, but mine, too. Have just some fallen, or have all? Have I fallen just a little short of God’s standard and if I really mean it this time, can my will make up the difference… or does my will trip on itself all the way and need a rescue? (Romans 3.19-23). Christ sends his Holy Spirit to finally convict our will of its bondage to sin and unrighteousness (John 16.8-9).

Was Always Striving, Never Good Enough.”

I have a friend who was right at home in the free will society. She grew up in a church that Erasmus would like. Well meaning, caring people often urged her on asking, “Are you making good choices? Have you committed your life to Christ?” But while it is most certainly true that there is no salvation for ungodly ones like us outside of Christ, telling someone “You must believe in Christ” only adds another big item to the will’s “to-do list,” and does not hand over to her any of Christ’s promises. So, my friend found herself constantly striving to obey, but never good enough.

Preaching the decision of your free will can result in a well-dressed, popular, and successful collection of congregants in the pews, and perhaps a lucrative business model for the parish as well. But it also heaps untold burdens and accomplishments on an eager will that ultimately collapses under their weight.

Worse yet, it instills a legalism that turns pastors, elders and talkative lay people into the righteousness police. The log in one’s own eye comes to mind. Either way, the burdened conscience is ultimately turned back on itself to be its own rescuer.

Baptism: Who Is the Subject of the Verb?

In the congregational setting, the reality of the bound will and the rescue from bondage that Christ alone accomplishes, manifests itself in pastoral care, preaching and hearing, and the sacraments, particularly baptism. In the town where I serve, if I were to approach most conversations as a theological argument to be won, I’d have no friends and likely not much effectiveness in my witness. But if I acquiesce to the predominate drinking water of the will, I misrepresent scripture and would eventually have to answer to the Lord for it. Christians of the Lutheran confession bring a rare, radical gift to the lunch table. So, in our church, every beloved sinner who joins or considers joining our congregation participates in a simple word study of the verb baptize. We begin by diagraming a simple sentence, such as: “Tommy throws the football.” Even those who slept through grammar class can pick out verb, subject, and the direct object. Then we diagram every sentence in which the verb “baptize” occurs in the New Testament (Matt 3.11; Mark 1.8; Luke 3.16; John 1.26, 33; Acts 16.15,33; Romans 6.3; Galatians 3.27). Pretty early in the exercise, participants realize for themselves that the Lord or the Lord’s agent (i.e., John the Baptist) is always the subject, the doer of the verb. This seems to be quite helpful in handing over to consciences God’s choice of them in their baptism.

So, in our church, every beloved sinner who joins or considers joining our congregation participates in a simple word study of the verb baptize.

Do We Believe This Ourselves?

When I left for college, my dear mother cautioned me: “Paul, you will pick up the habits of those around you… so remember who and whose you are.” We belong to God, we are not our own! And yet the myth of free will is so ubiquitous that it is hard to not pick up. Why, it’s un-American not to believe in the power of my free will to behave highly effectively and make good choices – never mind that the track record of our race tells a different story. The vast majority at the lunch table imbibe this trope automatically, indiscriminately… and the ready waiter that he is, Satan is always right there to fill our glasses again and again. The ice cubes jingle a deceptively delightful song as the Accuser grins and pours his potion into our glasses. Surrounded by so many friends at the table, it’s easy for each of us to acquiesce and go along with the popular, prevalent, unbiblical doctrine: the myth of my own free will. In all the communicating that is incumbent of our office as Jesus’ witnesses - conversations, emails, sermons, teaching, text messages, prayers - you and I are never more than a predicate or a pronoun away from picking up the human habit of endorsing a non-existent free will. Does Christ want us Lutherans to happily assert our distinctive accent into our conversations? An accent that is not ethnic but rather evangelical the foreign message that God is the justifier rather than you or me? I believe so.

Sent to the Luncheon, You and I Are

To disciples who were imprisoned by their own self-justification, the crucified and risen Christ breaks in at just the right time so that he might be just and justify these unrighteous ones by giving them faith in Him rather than in their own wills. “Peace be with you,” he declares. “As the Father has sent me, even so I am sending you” (John 20.21ff). He doesn’t encourage their free wills to behave better and choose Him, but instead he sends them to do the only thing that actually rescues a bound will from itself: retain and forgive sins. Jesus sends us to hand over Christ’s will in place of our own, to speak life and freedom where there would otherwise be only death and a will enthralled to itself. Rather than quietly going along with a free will, “are you making good decisions” culture, what happens when the law is allowed to do its holy work and expose the enormity of our sin? And then what would happen when that sin is finally forgiven on account of an even bigger Jesus?

Rather than quietly go along with a free will, “are you making good decisions” culture, what happens when the law is allowed to do its holy work and expose the enormity of our sin? And then what would happen when that sin is finally forgiven on account of an even bigger Jesus?

Walking out of a public building awhile back, I came upon a young friend I had not seen in months. Peter played baseball in college and now works in the oil field and only comes home every so often. I smiled and called out his name, gave him a big hug, and asked a pretty regular question since I had not seen in him a few months: “How are you?” His tone and countenance fell as he confessed into my right ear, “Not good. My little brother left on deployment yesterday and I wasn’t there to say goodbye because I was hungover. I knew he was leaving, and I blew it.” We released our hug, and I looked Peter in the eye with a smile and said, “Yep, that’s bad. You know what Jesus says about that?”

“What does he say?” Peter asked.

“He says that’s a sin; and you’re right, you screwed up… And do you know what he says about this sin of yours?”

Peter beckoned and I responded: “He says you are forgiven. In Jesus’ name, I forgive this sin of yours Peter.”

This 27-year-old baseballer and roughneck wrapped his arms around me in the parking lot and bawled and smiled at the same time, saying, “thank you, thank you… that is exactly what I needed.”

Thanks be to God and Christ’s church that a call was laid upon me, a duty given me to hand over Christ alone to Peter as his righteousness. But what if, what if… I had instead proffered the typical response which would have turned Peter back on his own allegedly free will to behave better? Would I not have left my dear, desperate friend dead in his sin?

The interactions and conversations of daily life, as well as ministry, tend to go better when I remember that what’s at stake is freeing burden consciences rather than winning a theological argument/debate. My witness is more effective when I confess the bondage of my own will first. “I believe that I cannot by my own understanding or effort…” The demons of prideful resistance are dialed down more effectively by humble confession than by a polemic spirit.

But humble confession certainly does not mean timidity. Indeed, in our conversations we Christians make assertions. We are not just milquetoast dialoguers who endlessly prolong a safe, polite conversation. Without arrogance and with confidence in Christ alone, we confess the truth of scripture, not of the self nor its feelings and opinions. We adhere to, persevere in, and confess the truth of the human will’s captivation to sin and Christ alone as our righteousness. Christians acknowledge adiaphora when so and make assertions when it matters (Matthew 10.32-33; II Timothy 4.15; I Peter 3.15). Like Paul, we get poured out by the Holy Spirit as a fresh drink offering rather than another stale ladleful from the tainted well of the will’s free choice. “What a droll exhorter he would be, who himself neither firmly believed nor consistently asserted the thing he was exhorting about!”7 humble confession certainly does not mean timidity. Indeed, in our conversations we Christians make assertions. We are not just milquetoast dialoguers who endlessly prolong a safe, polite conversation.

But humble confession certainly does not mean timidity. Indeed, in our conversations we Christians make assertions. We are not just milquetoast dialoguers who endlessly prolong a safe, polite conversation.

Perhaps most helpful is the realization that even in a raging, tottering culture, honest conversation full of humor and that theological gusto which Forde encourages tends to serve the gospel and burdened consciences better than polemics. Grumpy guests lose their place at the table. It’s the warm-hearted guests who have the “full conviction”8 that affords for a sense of humor, these are the ones who keep getting invited back into the conversation. These are also the ones who get crucified by the world for confessing Christ alone. As Jesus himself alerts us, “If they do these things to me when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?” (Luke 23.31).

In the locale where I serve, there are lots of people and lots of churches. My good friend at the Baptist megachurch is great about convening local pastors together for lunch every month and facilitating our praying together for the good of our community. It’s the best ministerial group I’ve ever been associated with. We all sit down for barbecue the second Tuesday of each month. I love the fellowship and continue to show up with a smile.

Showing up at the lunch table with a smile and waiting your turn, or being present in the hospital room, or at family dinner, or in the pulpit, and handing over a promise of forgiveness of sins, true life, and salvation from Christ crucified to those enthralled by their own free wills well that gives us and the other beggars around the table the only true freedom song. As witnesses to Christ, you and I get to show up at all kinds of “tables,” starting in our own homes and congregations. And we can do so smiling because we have a surprisingly unusual gift to hand over even as the water glasses are being refilled by that sneaky waiter.

Rev. Dr. Paul J. Owens is senior pastor of St. Paul Lutheran Church, New Braunfels, Texas.

Endnotes:

1Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, American Edition, 33 (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958), 294. The American Edition renders the last phrase as “aimed at the vital spot;” while “gone for the jugular” is Steven D. Paulson’s translation in his forward to Gerhard Forde’s The Captivation of the Will (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, 2005).

2The Holy Bible, English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2001). All subsequent citations in this article use the ESV version (unless otherwise noted).

3Forde, xvii.

4LW 33.13

5Oswald Bayer, Theology the Lutheran Way (Minneapolis, Minnesota: Fortress Press, 2017), 190.

6Clint Eastwood, director, Unforgiven (Warner Bros., 1992).

7see LW 3319-22. Christianity involves assertions; Christians are no Skeptics.

8plerophoria, as Paul and the writer to the Hebrews repeatedly refer to faith, Colossians 2.2; I Thessalonians 1.5; Hebrews 6.11; 10.22