24 minute read

Jubilee Interview

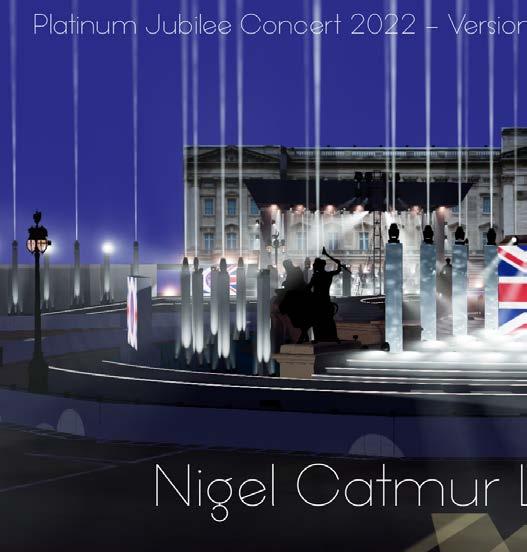

| Below:

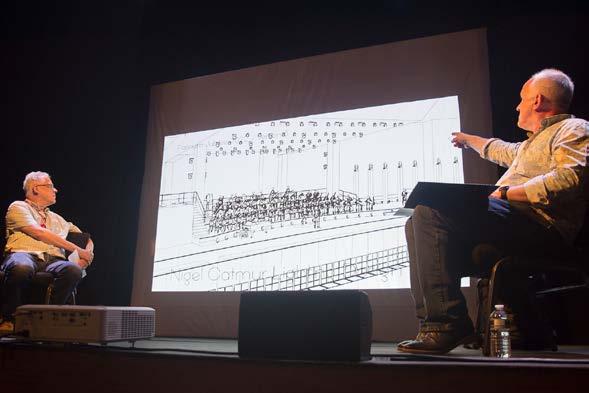

Bernie Davis (left) and Nigel Catmur

Advertisement

Lighting the Queen’s

Platinum Jubilee Concert

The STLD met with LD Nigel Catmur to discuss his work on the events to mark the jubilee culminating with an impressive concert.

Previous STLD meetings and articles in editions of Set and Light magazine have discussed the broadcasting of many royal events over the years, but few on quite such a superlative scale as the ‘Party at the Palace’ that celebrated the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II.

“The delivery of such a bombastically dazzling concert has to be considered even more of a triumph” wrote Neil McCormick, a critic in the Times, and Alex Petridis wrote in the Guardian: “…a show that grew more visually spectacular as night fell…”. To celebrate the Platinum Jubilee, a star-studded concert was broadcast live across the world featuring a vast range of performance genres spread over three stages outside Buckingham Palace. An evening of huge technical undertaking on many fronts led to a spectacular event, the visual impact of it felt by all who watched, even finding great praise in the media, but perhaps more so for those within the industry, a bastion of what we do that blew away the lockdown cobwebs and showed the world that this is a ‘viable industry’. To discuss the process of how an event on this scale and quality comes together, especially when under pressures such as approaching electrical storms, difficult schedules, unfortunately placed lamp posts and ever-changing ambient light levels, the STLD held a meeting hosted by Bernie Davis , where he talked with the concerts lighting designer Nigel Catmur to find out all about it.

Bernie Davis: Thanks, for joining us Nigel. How did you first get involved in this event?

Nigel Catmur: The concert was going to be produced entirely by BBC Studio Live Events. I’ve worked with the team on a lot of shows and about two years ago I got an inkling that the concert was probably going to come my way, but I wasn’t asked officially until last July. The tender for the set design contract was sent out to three set designers, ultimately being won by Ric Lipson of Stufish Entertainment Architects, but I was fortunate in that the lighting design came straight to me.

My team included gaffer Mark Gardiner, programmers Alex Mildenhall, Martin Higgins, Matt Lee and Oliver Lifely. Tom Young had originally planned to be one of the programmers but sadly had to pull out at the last minute for family reasons. Aaron Thomas, from PixMob, programmed the audience’s illuminating wristbands – we hadn’t worked with Aaron before, but he’s a great guy and fitted into the team perfectly. Joe Marter was

my excellent point of contact at Version 2, who provided most of the lighting rig. Martin and Alex were responsible for all the effects lighting, whilst Oli managed all the key lighting and the follow spots. We had four Lancelot follow spots, which are manual, and six Robo spots, which were all being driven through Oli’s system. And then Matt would drive the Hippotizers that fed the screens – not the projections, as they were controlled by a separate team.

Designing the lighting

With regard to the lighting, I came up with an idea and, once the set was signed off, I created an initial design to put forward to production. This is where WYSIWIG works extremely well, because we took the overall design and layout from the designer’s drawings and created it entirely in 3D. The production team was excited to get a sense of how I thought it might look. A 3D visualisation is always a really handy way to show and explain to everyone what up until that point has only existed in my head. In fact, it was an invaluable tool throughout because our time on site was so minimal with a lot of it spent in daylight. I think we only had about six hours of darkness per night, between 22.00 and 04.00, so most of the programming had to be done on Depence [powerful real-time visualisation software used to simulate multimedia shows and installations]. Alex took my model from WYSIWYG and transferred it into Depence, through which he and Martin did the bulk of the programming, which was absolutely phenomenal.

We had planned to have three days of WYSIWYG and visualisation, one day would be offsite with Alex and myself, then Tom would join us at the location – it made sense to build the system once, rather than twice, because we knew we were going to keep the visualiser with us through the whole period. We had two days getting to grips with programming before the rehearsals started on the Tuesday and Wednesday. On the Thursday, there was Trooping the Colour and the Beacon lighting, which involved a whole different event core and lighting programme, and then Friday was rehearsals during the day and a dress run at night. The Palace stage wasn’t actually installed until Thursday night, the build was held up because of the Beacon event, so we’d rehearsed acts without the stage and, of course, it was daylight anyway. As always, the schedule was quite a challenge, but at least we didn’t have to worry about disturbing any Royal residents, because the whole front section of the Palace is currently being renovated and is a building site, so we could programme all through the night and flash lights at the windows, no problem.

BD: I’ve often found that what clients want to build and what they can afford to build doesn’t always suit the lighting – did that trouble you at all?

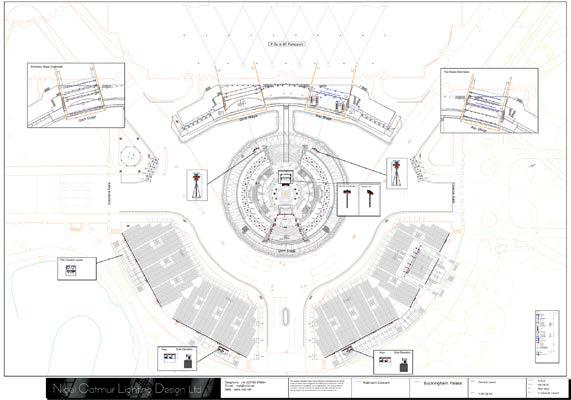

NC: Yes. The final set design had four stages that became known as: the QVM, Orchestra, Palace, and Pop. You could argue that the Orchestra, Palace and Pop were effectively one big wide stage, but they were three discrete areas. The real challenge was that we had no height, so we ended up adding three vertical truss towers as mountings to provide front lighting, one either side for the orchestra and pop stages, and one in the middle to hold key lights for the Palace stage and catwalk. We had positions at the back of the seating blocks for lighting the QVM stage. All the key lighting was done with Robe BMFLs and/or spots and then front of house, we had four Lancelot spots, two on either side.

A lot of planning work had gone into making sure we could actually light the front of the QVM stage, because there are two lampposts at the end of the Mall on either side which prevented us being able to place our lamps directly in front of the stage. If we’d put them where we wanted, they’d have been shadowing the street lamp, giving us a lovely lamppost gobo over every artist! However, Mark and I had been on site for a number of

days before we spotted that the follow spot positions weren’t actually where they should’ve been.

Mark Gardiner: The structures for mounting the follow spots were constructed out of studio pods stacked one on top of the other and they appeared to be in the right place. The staircases hadn’t been built yet, so we’d not been able to get up and look at all the angles, but it eventually transpired that the positions were actually 5m out – which is critical for a follow spot with a lamppost in the way! To resolve it, Star Live, who built all the structures and stages, came along with some roller blocks and ratchet straps and they dragged the towers into their correct positions – it would’ve been a lot easier when the crane was still there!

NC: Another challenge was the throw range of the lights: the distance from the front follow spots at the back of the seating to the QVM stage was about 61m, but they could also be aimed past the QVM to hit the Palace stage, which was about 138m away. For that reason, we went with 4K Lancelots which would give us the kind of firepower we desperately needed.

The lack of height also meant we didn’t have any way of lighting the audience; whilst not an issue during daylight, we’d obviously still want to see the crowd once it got dark. The design concept incorporated 70 towers around the stages – one for each year of Her Majesty’s reign – and they would give us our only height. 8 of the towers on the main stage would have video on them, the remaining 62 towers would be topped with LED lamps for lighting out into the audience. On top of the washes, we had hybrid lamps whose primary purpose was to create light beams in the air but, by tipping them outwards, they could add more front light on the audience. However, we soon realised that the LEDs had more than enough poke and, combined with the LED Pars that were round the back of the audience, we could put a decent amount of colour and light into the crowd.

The Palace itself needed to be lit, and I knew that projectors were going to be used to display visual content onto the front facade. Given that projectors are very bright light sources, if we could gain control of them whenever they were not being used to project creative content, then they could be very effective as floodlighting. We projected a still image of white and, as the daylight gently dropped, so the Palace gradually began to come to life, in a most wonderful floodlighting effect.

I wanted a clean look with real impact, which I achieved by pointing lamps directly into the camera, as we’d done 20 years ago, when I operated on the Party in the Palace. It works incredibly well, particularly on TV without affecting the live audience’s enjoyment during daylight. As Queen performed in that opening shot, we aimed every light in white into the lens and it brings such a heightened level of excitement.

I wanted to develop that idea throughout so, going into the evening, I was very clear that there would be no heavily saturated colours early on. We’d keep it white initially, then shift into pastel shades, and slowly work the colour in until we got to the bite point of the evening, when suddenly the lighting really started to pop – which, incidentally, in London on June 4 is around 21.27. But the drop-off between 21:15 and 21.27 isn’t linear, you feel it dropping and what’s really important when doing this type of show, is to have constant balance control. A light that looks like a fantastic twinkle into the lens at 20.00 as the concert starts will give you the biggest burnout just 45 minutes later. So, your programmers and operating team have got to keep a constant measure, gently pulling the lighting back the whole time.

A major advancement in technology that we benefitted from was the ability to control the brightness of the LED screens. Brightness and contrast were run on single channels of the desk so Matt, our content programmer, could lower the intensity of the screens as we brought down the lighting levels. We started with the screens at 80%, which is Piccadilly Circus level, and ended up running them at 4%; sadly, we didn’t have the same degree of control of the screens down the Mall, although we eventually did manage to get them down too. Of course, another key factor is the weather, you might set everything during the dress rehearsal but it could be completely different by the next day.

We faced a whole catalogue of reasons, which we nicknamed ‘Platinum Handcuffs’, that hampered our chances of putting on the show. These included: Changing the Guard, which takes up 2 hours of every day; horses would randomly need to come through; the

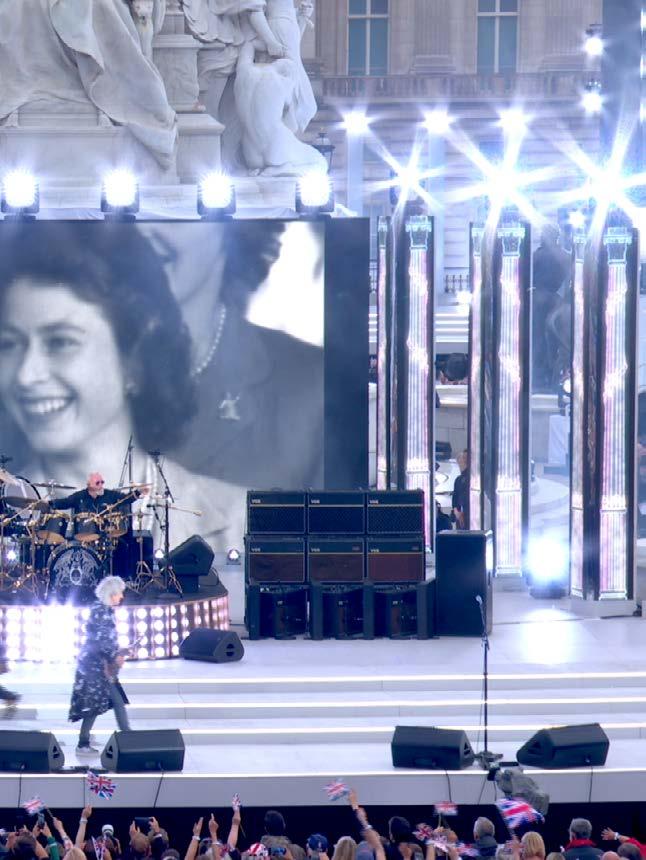

| Above:

Packing a punch, before daylight fades the lighting still incredibly effective pictured here with Queen onstage.

whole site had to be kept clear, because emergency police access could be needed at any time. The international media slot for live pieces to camera was at 22.30 every night (often at lunchtime too), so sound would have to turn off the PA for the duration, which could stretch from 22.30 until 02.00, because of all the different time zones. Crews would often leave their incredibly bright light panels switched on at the back of the seating block, which was frustrating when we were trying to programme our lighting. The biggest disruption, though, would be a thunderstorm, as we’d be required to power down the whole site and evacuate, which did happen on the first rehearsal day.

MG: For logistical reasons, power for the whole event was run from four separate generator sites, each of which had four massive generators. For those that know London well, lightning tends to gravitate towards the capital’s large, green, lush parks, rather than its tall buildings. With Green Park right next to us, there was a specific lightning risk assessment and procedure. A warning would be raised if lightning was 12 miles away; at 8 miles, people in follow spot towers, tower cranes and the aerial cameras, etc. must power equipment down and vacate their positions; finally, within 8 miles, it was an entire site power down, because the electrical storm could be on top of us within a couple of minutes.

Every department had to devise a strategy. We had nine distro and dimmer stations across the whole area, so each team member had responsibility for a distro and they would report to me in a particular order so I could be certain that everything had been shut down properly. I would then inform production by radio that we had successfully isolated ourselves. I also had to make sure the front of house team had vacated, because it’s very easy not to hear or see a message when working, so whilst everyone was running away, I was running up staircases to make sure they’d all got out!

It was a BBC Events’ decision to power down and isolate the equipment; aside from health and safety, there was also a business implication. If something was destroyed by a lightning strike, there was a big risk both in the financial cost and the potential of not being able to replace equipment in time for the show. Therefore, it wasn’t just about flicking the breakers, it was about disconnecting the power locks across the whole site; generators were isolated from the system, so that if a front of house position did get hit, the energy surge wouldn’t take out the four generators, or any distros, or the OB trucks. Everything would be disconnected and it was accepted that it would take considerable time to get the site back up and running again. In the event, it took about 4 hours from the minute we had to power down to being back up and working again, so a lot of time was lost.

BD: Having fitted in around all these problems, how much time did you get to rehearse the acts?

NC: Everyone rehearsed, although it was mostly irrelevant to us, until the Friday night, because before then, rehearsals were in broad daylight. The dress rehearsal was scheduled for exactly the same time as the concert was going to be – and it ran to time as well, bizarrely.

| Above:

The projection onto Buckingham Palace having huge impact all the way down the Mall as the crowds can see the finer details on the I-Mag screens.

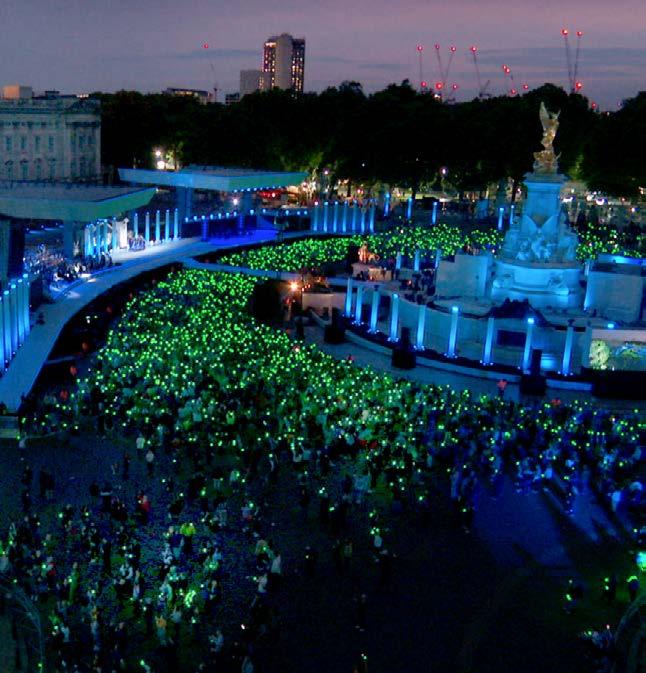

| Above:

Tree of trees, shimmering alongside the audiences wrist bands as the sunsets across London.

| Below:

Site plan showing the stage layouts and Nigel’s lighting positions.

| Below:

Nigel talking through lighting the orchestra stage. We’d approached the design with the view that the effect lighting was going to happen regardless, getting the correct balance of the key lighting was what concerned us. The effect lighting would need balancing too, but at least we could get it programmed ready with the structure of the songs, the choice of colours, etc. In the days leading up, I’d developed a sort of mantra, where I’d look at the time and say:: “OK, it’s 20.50, so we’ll be doing Queen… It’s 21.27, we’ll be doing Andrea Bocelli… Duran Duran would be on now”, just so that the team could look out the window and get a reference for a look on the camera, because I knew they were going to be riding the lights and pulling them back live. But the key lighting and the effects lighting were two definite entities that both had to be kept separate. It basically meant that Ollie, who was controlling all of the key lighting, had one hell of a night on the Friday, there was a lot of swearing, but he did an amazing job, because he had one chance of seeing it on camera and getting the balance right for the next night.

The way the timing worked out, Andrea Bocelli was on stage at the point when the lighting really began to read and once we were into Duran Duran, then the projections on the Palace started. They were 3D mapped using 24 projectors, which means projections were also fired into the side aspects of the facade, rather than just being flat projected from the front. For the lighting, smoke added a huge lift because, although we did get that lovely sunset halfway through, it was just a dull evening, really. We were praying for a blue sky, and if we’d have had the perfect sunset then the whole thing event have been even better, if that’s possible.

BD: I have to say, it was so well balanced for camera, you’d never have believed that it was done in such a short time schedule with barely any rehearsals, under that sort of pressure, so well done to all the team for pulling that together. Right from the start of the concert, light levels were changing constantly and presumably that meant the exposure on the cameras was too?

NC: It was, and the solution to that problem is to make sure you have the very best racks engineer in the country and just tell them to get on with it! No, we had Dave Roberts and his team; Dave does Strictly and he’s absolutely brilliant, he’s got the right personality and fits in. Although he’s completely remote from us, sitting in a truck somewhere, he and his A-list crew of Oli Richards, James Kozlowski and Dave Griffiths were looking after vision, and were all very much part of the team. We all worked in harmony, keeping an eye on this constant,

| Left:

The cast of Hamilton on stage as daylight begins to fade.

one-way journey, where we were only ever opening up the cameras and bringing the lights down. From a lighting programmer’s point of view, you can have one level stored – as the ‘brightness’ – and so long as you keep bringing that down throughout the concert, it’ll balance.

BD: And so was Oli, as your programmer responsible for lighting faces, in constant contact with vision, or was it just an assumed thing that they were just keeping up with him?

NC: No, we were constantly talking, the dialogue was continuous, and often quite… short: “CAMERA 19, vision!! … Thank you!” Ha ha.

BD: There must have been a lot of collaboration involving the screen and projection graphics, how much did you get involved in that?

NC: We had five creative producers who were coming up with lots of ideas for the show and they liaised with North House Media, who had been given a brief to create the projection content, so we’d have regular reality checks with them. Initially, North House had a tendency to create imagery that contained lots of black, which doesn’t read well on camera while it’s still daylight, say when a screen is in the background of a close-up of the artist. It’ll just look grey, so I encouraged them to put a bit more base level in their blacks, or just use less black. It was really good because the teams did listen to us, and they responded accordingly – I mean there was still one piece that went a little further than I would have, but generally it all worked. Another issue that emerge was the framing within the visual content of the projections, because any part of the image that hit a window would effectively become blocked out, because glass is unsuitable for being projected onto. We therefore suggested the producers should avoid creating content that was too static. This was to prevent key elements of the projected image being lost by lingering across any windows; fluid movement of the performance meant the viewer’s eye could fill in all the briefly missing bits.

North House also coordinated brilliantly with the drone people; before this event, we’d all seen drones and all seen projections, but what I think was a first on TV, was witnessing projections and drones working interactively; the imagery all weaved together and I think that worked extremely well. Interestingly, we hadn’t rehearsed with the full fleet of drones, we only worked with 12 craft, which at least gave us an idea of the brightness. Obviously, we didn’t want the projection to overpower the aerial display

| Right:

A similar real world shot to the render above from WYSIWYG. so, during the drones sequences, we ran the projectors at slightly lower levels to achieve a better balance for camera.

BD: When you’re doing lighting stabs to go with music, what do you listen to, because the pictures are not necessarily in the same time as the PA sound, and with the digital delay in cameras as well, what do you work to?

NC: The delay is about 2 frames, which you don’t tend to notice on a stab. The majority of the show was timecoded, which was synced with the conductor of the live orchestra, and everyone was playing to a click track, which is fairly standard. We programmed to timecode and used software called Reaper, which displays sounds in waveforms, so you can see the hits and line the stabs up with them. The lighting system probably has a similar amount of delay in it, but if Alex and Martin saw that the cues were out, they’d all be out the same amount, so they would just advance the timecode accordingly.

The only exception was Queen’s We Will Rock You, which Alex did as manual stabs, anticipating and hitting early. Queen didn’t perform to a click, they played live, but their timing for We Will Rock You was critical, because they had to be perfectly in sync with the Paddington Bear opening VT, which famously ended with the Queen tapping the iconic ‘boom boom cha’ on her teacup. So, Queen started with a click track and then once they got going, they just did their own thing and we pulled down the volume. The added complication was that only about seven people knew about the Paddington VT, and we could never rehearse with it because if word got out, then the whole VT would be pulled. Trying to explain what had to happen when the content was entirely secret, was tricky, the most you could do was intimate, “Think 2012 Daniel Craig VT”. That’s one of very few secrets I’ve managed to keep right until the end!

The concert was shot with 32 cameras, I think. They were split over two trucks. Some were used the next day for the Pageant and the Lord Mayor’s Show, so there were double ups. I can definitely remember Camera 29 and I’m sure there were a couple more after that. It was shot in 4K HDR, which added its own challenges of monitoring, because to process the signal down to 1920 adds a time delay. Plus the RF Steadicams had their delay as well, so all the other cameras were delayed to match them – dealing with the delays on this job was quite phenomenal.

With both a live and TV audience, which do you light for?

NC: Ultimately, the number of people watching it live was about 22,000, the number of people watching the broadcast was, well, certainly on the night, 13.8 million and I believe with catch-up and international sales, it’s gone through the roof. So, in my opinion, one has to take the camera more seriously, but I’m also acutely aware that the live audience are important, because if they’re not seeing it and getting the enjoyment of feeling a part of it, then they won’t add the energy that a live audience adds to a broadcast. But, you can make it look good for both, and the trick is to just take the key light down a little, the cameras can open up,

| Below:

A render from WYSIWYG used by Nigel and his team visualise the concerts lighting and camera angles.

| Below:

A shot showing the incredible depth of the 3D projection mapping wrapping around the architectural features of Buckingham Palace. then all the lighting will look exciting on camera, and your IMAG screens will still look good too.

Typically when lighting TV shows, you can look out and barely see the follow spot by eye, but because we were coming out of daylight, our key levels were quite high. On an event like this, once it gets to nighttime, I always try and set the camera exposure to about f4, which is quite a small aperture for a studio show, which is more likely to be running at f2.7-f3.2. By closing down the iris a little, your spot can be brighter and therefore your live audience have got more chance of seeing where you’re pointing.

Version 2 provided most of the rig. I wanted Robe BMFLs for the keying, because I needed the brightness and reliability, and I knew we could waterproof them. Everything else had to be IP65 (unless it was rigged under the roof), that was the driving force, then it came down to availability. We wanted Robe iSpiiders but couldn’t get hold of any, so we ended up with the PROLiGHTS PanoramaIP WBX, they are heavy but have phenomenal effects. ELP White Light supplied the lighting inside the Palace.

Wristbands

The control system for the wristbands is highly complicated. Alex was going to operate them as part of the main rig, but after a 20-minute explanation from Aaron from PixMob, none of us were any the wiser. It’s a very clever system, the wristbands respond accordingly when triggered via infrared LED pars that send out coded signals. You can set up different zones or ‘layers’ to control separate groups differently. Aaron spent a lot of time programming it, but I think the end result was worth it.

BD: It certainly was. Everybody has been blown away by how that concert looked. I think there was a timing about the Jubilee anyway, we’d been through so many years of seeing the industry being pulled apart, almost stopped completely. This amazing concert seemed to be the first real occasion that a crowd of people was allowed and able to enjoy themselves, and full marks to Nigel and everyone for pulling that off. Thanks for coming along today, Nigel, it’s been really enjoyable and very much appreciated.

The meeting was recorded by the students and staff of RADA, and the video of this can be seen on the STLD website. We thank RADA for all their support and generosity in helping to present this meeting.