9 minute read

Librarianship AND “Theory of Knowledge

Amber Edwards

Librarian

Advertisement

“I’d like to teach TOK. I have a degree in Philosophy which I think would be useful and I think I’d really enjoy it”

“You know it’s not Philosophy?”

“Yeah, of course I know that.”

I did not know that. I thought I would be revisiting all the texts I studied in my undergraduate degree and I would be able to dig out my old lecture notes and draw on the knowledge I gained from the endless hours of reading long, philosophical arguments where I did not understand all that much. I thought Philosophy and Theory of Knowledge (TOK) were so closely aligned, and it was just a more accessible version of epistemology for IB students. It wasn’t until I attended an online webinar in preparation for teaching TOK by Ric Sims, one of the gurus of the TOK world where somebody asked him the difference between the two subjects, that I realised this was not what I expected it to be. I had been so focused on trying to learn how to become a teacher instead of a librarian, mainly by reading radical texts like Brookfield’s ‘Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher’ (2017), Allen’s ‘The Cynical Educator’ (2017) and Illich’s ‘Deschooling Society’ (1971), admittedly, probably not the most ideal texts to be reading for a smooth, light introduction to teaching. I thought the subject matter would flow so naturally and I would just have to work out the best way of getting the message across to students. Once I started teaching the subject, what I actually found was very different. It was not my background in Philosophy that was beneficial to teaching TOK, but rather my experience as a librarian.

What is TOK?

Theory of Knowledge is a core subject in the IB Diploma Programme and is designed for students to reflect on how they can know what they think they know. It sits alongside the academic subject groups and is designed to almost be a critical reflection on what they learn within those subjects, allowing them to explore how they come to know what they learn, the nature of truth within those subject areas, and the role knowledge plays within cultures around the world. The 2022 syllabus for Theory of Knowledge is structured according to a ‘Knowledge Framework’, an organisational tool that allows teachers to explore the TOK themes and content in greater detail. The Knowledge Framework consists of four elements;

Scope: exploring the nature of knowledge and how it fits with everything we know

Perspectives: the importance and influence different perspectives have on knowledge

Methods and Tools: the methods, tools and practices used to produce knowledge

Ethics: how ethical values are built into the quest for knowledge

The course is divided into different elements. It begins with the Core theme, Knowledge and the Knower which focuses on the personal reflection of the students themselves and their own experiences of how they know what they know and how they make sense of the world around them. Each student is then required to study at least two optional themes which help to frame the way we make sense of knowledge in specific contexts. The optional themes are; Knowledge & Language, Knowledge & Technology, Knowledge & Politics, Knowledge & Indigenous Societies, and Knowledge & Religion. The course then goes on to look specifically at different Areas of Knowledge, namely; The Arts, History, Human Sciences, Mathematics and Natural Sciences.

The Librarian/TOK teacher overlap

Being the Librarian for both Junior and Senior school provides a unique opportunity to see the development of key skills in pupils across St George’s. In the Autumn term of 2020, the school restrictions for COVID-19 meant that Junior School pupils were not permitted to come to the library for their weekly library lesson, and so, as such library lessons have taken place in their classrooms with a selection of books for them to borrow, and often some additional element of information literacy. These sessions are largely centred on The Fosil Group’s Framework of Skills for Inquiry Learning which is based around the idea that students develop information literacy skills with more success through inquiry and by conducting their own research (Toerien, 2021), as they would naturally in their timetabled lessons.

Information Literacy is defined as “The ability to think critically and make balanced judgements about any information we find and use.” (CILIP, 2021a) While there are many different models and frameworks, it is typically made up of eight competencies that an information literate person possesses.

These are: 1. Having a need for information 2. Knowledge of available resources 3. An awareness of how to find information 4. Knowledge of how to evaluate results 5. Knowledge of how to work with or exploit results 6. Knowledge of ethics and responsibility of using information 7. Knowledge of how to communicate or share their findings 8. Knowledge of how to manage their findings (CILIP, 2021b)

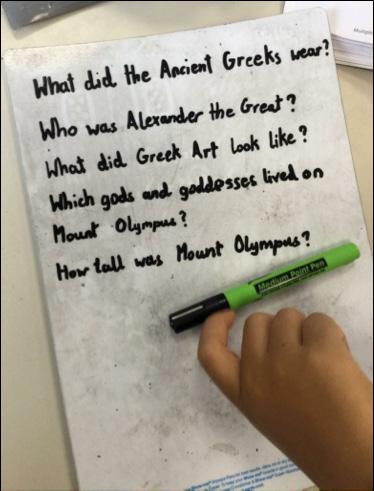

Using these two frameworks and definitions within library lessons practically has seen work being conducted with year three exploring the differences between fiction and non-fiction resources, as well as different types of information resources such as dictionaries, encyclopaedias, maps, etc. Year four has been focused on formulating their information needs as questions, specifically through their study of Ancient Greece and how they can extract keywords from those questions to conduct a basic search for information.

The teaching of information evaluation in these particular examples highlighted the first instance of synonymity between librarianship and

TOK. Seeking information on Ancient Greece necessitated conversations surrounding the validity and accuracy of the information they might find, what authority the authors of the information have to be able to say such things, and even what authority their teachers have on the subject. Exploring these issues encourages pupils to think critically about the information they find, the skills of which map almost directly onto those within an IB TOK class where students are expected to critically assess what they know and how they know it, using very similar methods of inquiry.

The library sessions with year 6 were particularly rewarding due in large part to having more time to spend with them; a dedicated timetabled session every week with each class allowed for a planned, scaffolded programme of information literacy instruction. This was very different from their previous library lessons where they simply came to the library to check out books and explore the collections, and it was a good opportunity to begin implementing key skills they can build on throughout their school life. These lessons began by reviewing the basic practical elements of using the library, e.g. searching for resources using the library catalogue, requesting books, accessing ebooks, etc., however, the information evaluation aspect soon brought more of a TOK-esque nature to the lessons.

Explorations of critical literacy began by reading aloud to the pupils the fairy tale Little Red Riding Hood, a story they are all familiar with and can recall with ease. This was followed by reading The Wolf’s Story: What Really Happened to Little Red Riding Hood, a picture book which tells the fairy tale of Little Red Riding Hood from the perspective of the wolf. Reading both of these stories facilitated discussions around the importance of perspectives and the factors contributing to the different elements which make up a person’s perspective or point of view. Pupils were actively seeking defences for the wolf’s behaviour considering it might have had a family to protect and reflecting on why the wolf might act hostile after constantly being depicted in children’s literature as the villain. Pupils were asking why we should stop only at those two perspectives and suggested we should listen to the grandma’s version of events, or even the flowers and the trees in the forest (year 6 are very imaginative!). Discussions soon moved from perspectives to the nature of truth; how Little Red Riding Hood might be lying and what is truth anyway, and can we ever even know the truth about anything. The conversation even moved to the pupils contributing their thoughts on the truth and falsities of COVID-19 and the danger that false information could have on public health. All of these questions and considerations fall very much within the scope of TOK where it is hoped students will develop their critical thinking skills and be able to critically assess everything they have learned and come to know up until now. Truth is an essential concept within TOK and the conversations between year six and the TOK classes were astoundingly similar.

Information literacy and critical thinking skills do not peak at junior school. The FOSIL Skills Framework encompasses skills needed for students to advance all the way through to year 13, and the Chartered Institute for Library and Information Professional’s (CILIP) model of Information Literacy looks at it as a life-long skill, empowering us “as citizens to reach and express informed views and to engage fully with society” (CILIP, 2018), exploring the impact being information literate has in contexts such as citizenship, health and in the workplace. IB students often have a series of sessions each year covering research skills in preparation for writing their Extended Essays, something which can be overwhelming to them when they are encountering the concepts for the first time. This being said, it would be hugely beneficial to implement a formal, timetabled, scaffolded information literacy programme for the senior school which would complement their curriculum-led subjects and prepare them with the research skills needed to undertake project-based school work at any level. Giving students the opportunity to learn such skills, reflect critically on the information they are presented with and question what they know will not only enhance their engagement with their schoolwork, and prepare them to undertake the reflectivity of TOK when they reach IB level, a subject typically criticised by students because it is so unfamiliar to them, but it will also serve to make them critically reflective citizens of the world, something we could all benefit from in the era of Fake News and the mass availability of information.

*The title of this article is a play on the typical librarianship concept of using Boolean operator search terms to find information. ‘AND’ is used to narrow search results and to instruct search engines that ALL search terms should be present in the retrieved results. Phrase searching involves putting speech marks around keywords to make the search results more relevant and to retrieve results containing a phrase rather than a set of keywords in a random order. Putting brackets around search terms allows you to group together similar search terms and to tell the computer which search string to prioritise.

References

CILIP. (2018). CILIP Definition of Information Literacy 2018. London: CILIP. Available from https://infolit.org. uk/ILdefinitionCILIP2018.pdf [accessed 31 January 2021].

CILIP. (2021a). Information Literacy. London: CILIP. Available from https:// infolit.org.uk/ [accessed 31 January 2021].

CILIP. (2021b). Definitions & models. London: CILIP. Available from https:// infolit.org.uk/definitions-models/ [accessed 31 January 2021].

Toerien, D. (2021). The FOSIL Group: Advancing Inquiry Learning. Available from https://fosil.org.uk/ [accessed 31 January 2021].