6 minute read

A Proud Moment to Remember

How Stetson helped prepare teachers and students for the 1960s' desegregation of public school classrooms in Volusia County.

An online-exclusive article submitted by Elizabeth Walker Mechling ’67 and Jay Mechling ’67

For a few years now, Stetson faculty and students have been researching and writing about the racial integration at Stetson in the early 1960s and about Stetson’s role in the larger effort to end Jim Crow segregation in DeLand and in Volusia County.

We want to add to this history our own story about our personal involvement in two projects at Stetson, projects that reached out to enrich the education and cultural experience of African American children in DeLand and nearby.

At the start of the spring semester in 1965, Elizabeth (then-Betty Walker) was asked to be a teacher’s aide for a preschool class to be held on campus, in the Stoudemire House (sometimes called the “red brick palace,” now home to the Cross-Cultural Center). As it turned out, the teacher, an African American woman, left the job after a few days, which meant Elizabeth had to teach the preschool class by herself for the remainder of that semester.

Elizabeth bravely took on the assignment, finding ideas and resources for teaching preschool. She was a double-major in English and Speech/Drama, but she adapted quickly to the challenge of teaching a preschool class consisting of about a dozen African American children and one white child, Harry Tuttle. Young Harry was the son of Arthur F. Tuttle, the assistant dean to Dean William Hugh McEniry and director of Special Projects — a fact that turns out to be important in this story.

Teaching that preschool class is one of Elizabeth’s fondest memories of our years (1963-1967) at Stetson, and we assumed for years that Stetson was sponsoring a Head Start program. Out of curiosity, though, we looked at the history of Head Start, and the program was piloted in the summer of 1965 and formally instituted in the fall of 1965. Clearly, the class Elizabeth taught in the spring of 1965 was not a Head Start class but something Stetson initiated on its own.

Solving Our Puzzle

Seeking more insight, we solicited the help of Elizabeth (Beth) Maycumber, archivist at Stetson’s duPont-Ball Library Archives and Special Collections. We knew it was a long shot to find any records from nearly 60 years ago, but we lucked out. Beth found files that solved our puzzle.

Here is the story: The files Beth found document a 1965 project that received a substantial grant from the U.S. Office of Education to develop “a comprehensive county-wide cooperative impact program to identify and solve problems incident to school desegregation by furthering Personal Responsibility for Individual Development through the Education of teachers,” PRIDE for short. Bethune-Cookman College and the Volusia County Board of Education were partners with Stetson in the project, which ran from March 1965 to December 1969. The main feature of the program was summer workshops in English, History and American Studies for teachers, as well as the creation of a research center focused on preschool and primary school students — research shared with the Volusia County Demonstration School.

Although we found no documents specifically about the class Elizabeth taught, we surmise her class was part of the larger project’s aims. “Difference in caste, class and culture must be understood and appreciated at all levels of learning from nursery school to adult education,” explained the grant application.

Elizabeth was on the front line of this effort, without realizing she was taking part in the larger project.

Arthur Tuttle was the project director for PRIDE. He had such confidence in the program that he put his own son, Harry, in the class. In retrospect, Elizabeth and I have marveled at the courage it must have taken for the African American parents of those children to send their preschool sons and daughters off to a half-day at a white university. And, although it does not take that same courage, we marvel at Arthur Tuttle’s thinking that it was important to expose his son to an integrated classroom at a young age.

More to the Story

That’s not the end of our story.

Elizabeth and I were intrigued by a very brief mention in the grant proposal about Stover Theatre’s contribution to the project, including mounting a production of political satirist Stan Freberg’s play, “Stan Freberg Presents the United States of America,” and a cryptic comment about children’s theater.

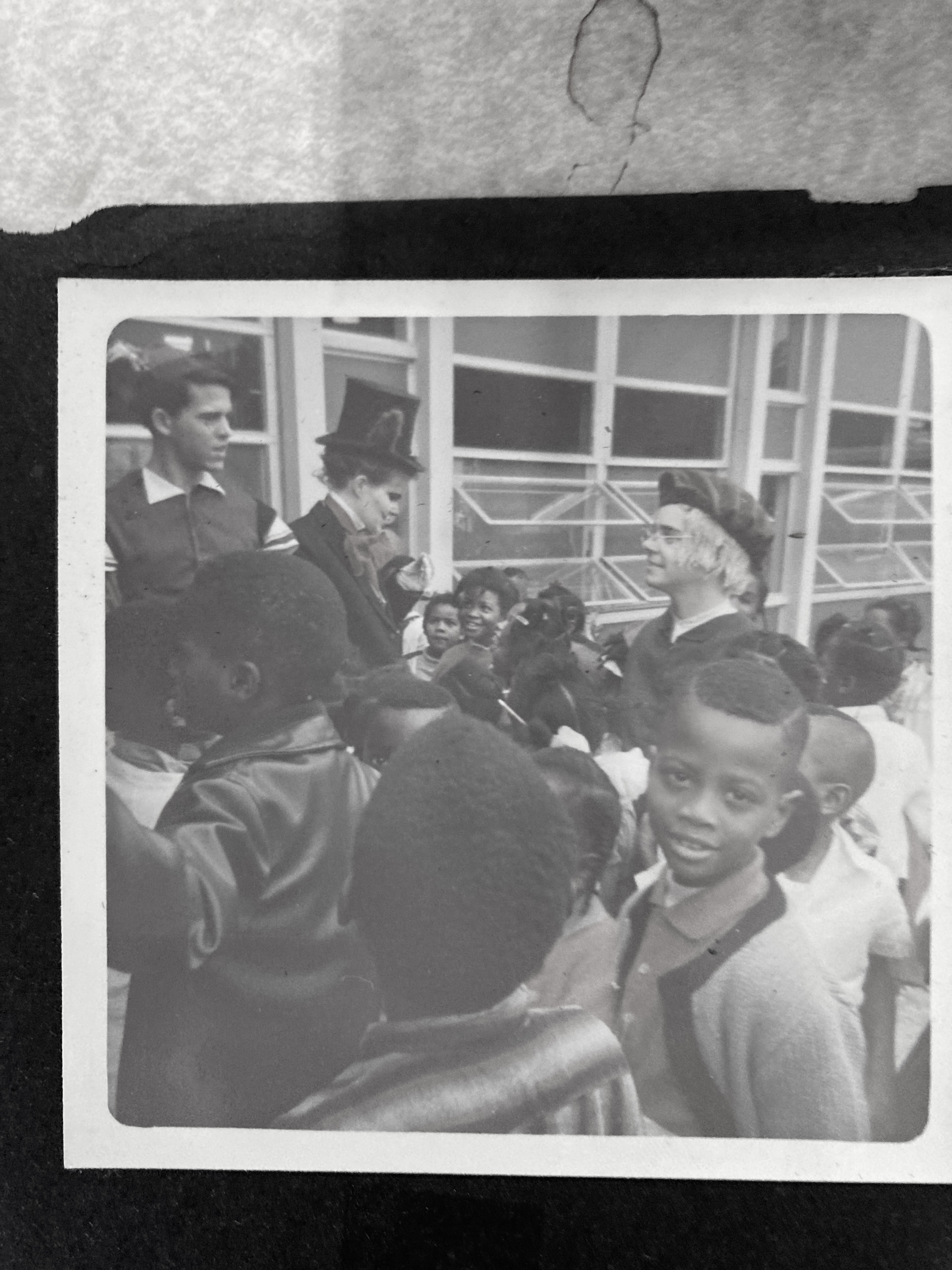

We were active in Stover productions in our years at Stetson, and we do not recollect a production of the Freberg play, which might have been mounted in the summer. But we did have firsthand experience bringing a children’s theater production of “Pinocchio” in January 1966 to local primary schools, including at least one school (Starke Elementary School) for African American students. Elizabeth and I were both in Company A (there were two companies going to different schools). We contacted the student who directed the play, Linda Rogers, who was a year ahead of us and who had her work-study grant in Stover. Still in touch with Linda on Facebook these 60 years later, we asked her what she remembered about that children’s theater project.

Not only did she remember it, but she even had some snapshots to share.

Our story is not about the integration of the Stetson student body, a story well-told elsewhere; nor is it about Stetson’s efforts to help desegregate the town of DeLand in the late 1950s and early 1960s (also a worthy story). Ours is about Stetson’s response to the landmark 1954 Supreme Court desegregation decision: Brown v. Board of Education and the challenge of preparing teachers and students for the desegregation of public school classrooms in Volusia County.

Looking back from the present, it is not easy to appreciate fully the bravery it took for African American students to sit-in on lunch counters in DeLand, for white students as early as 1957 to press Stetson to admit African American students, and for Stetson to host an integrated pre-school program in 1965.

One of Elizabeth’s memories around this time was when we both, on the debate team, did a program at the Methodist church downtown. During the social hour that followed, Elizabeth told a few women about the class she was teaching. One woman asked, “How can you bear to touch those children?” There it was.

Elizabeth replied, “I love teaching and hugging those children. How could I dare not to?” She walked away stunned at such a brazen racist comment from a nice church lady.

Then-President J. Ollie Edmunds and Dean McEniry displayed amazing courage in integrating the student body and in creating a large project meant to serve Volusia children and teachers as they prepared for a new era in racial integration.

These are proud moments in Stetson’s history.