7 minute read

EXpERIENCING A TOTAL SOLAR ECLIpSE

from SCIOS July 2023 Volume 70

by STAWA

About the Authors

Dr Maree Baddock is Director of Teaching and Learning at Helena College. Maree is still excited by science after many years in education and is considering taking up eclipse chasing as her latest hobby.

Victoria Baddock is currently completing Year 10 at Helena College.

The study of eclipses in terms of the relative positions of the earth, sun and moon are part of the Year 7 Science syllabus. Photographs of stars during eclipses was also used to verify Einstein’s general theory of relativity. It is always easier to bring these to life when there is a local example of this phenomenon. In April this year, a hybrid eclipse occurred, with totality being visible in a very small area around Exmouth in our state’s north. I was fortunate to view this eclipse with my family from a cruise ship that anchored just off Exmouth.

Hybrid eclipses are relatively rare. A hybrid eclipse occurs when it moves from being an annular eclipse (a ‘ring of fire’ being visible around the sun as the moon appears to be slightly smaller than the sun) to a total eclipse, where the moon appears to fully cover the sun, and back to an annular eclipse.

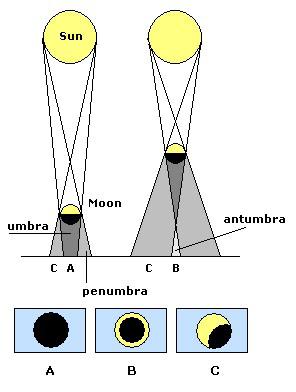

The type of eclipse will depend on where the shadow created by the moon is positioned. A total eclipse is observed from the umbra or the dark middle part of the shadow. At this point, the sun is completely obscured by the moon, the sky darkens, stars and the sun’s corona become visible. An annular eclipse is observed when viewed in the antumbra, or the part of the shadow just behind the umbra. A hybrid eclipse is primarily due to the curvature of the Earth’s surface (Figure 1). It is not possible to view both parts of the hybrid eclipse due to the speed of the movement of the shadow over the Earth’s surface. A partial eclipse is observed when the viewer is in the penumbra. Perth experienced a partial eclipse.

The effect of gravity on light, which formed part of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, was verified by analysing photographs taken of a designated set of stars during a total eclipse and earlier in the year. The first photos were taken by Arthur Eddington and his team in 1919. While his analysis that light did indeed bend was accepted by many in the scientific community, there was concern that the data was insufficient as only a few stars were visible for the analysis. More photographs were taken during the solar eclipse on 21 September, 1922 on Eighty Mile Beach in Western Australia, where totality lasted nearly six minutes. At the time, it was a very difficult place to access (no roads or ports) but the results that were eventually obtained were considered definitive proof of the bending of light by the sun. In researching how to photograph the eclipse, I came across articles on how to replicate this experiment. Interestingly, it is almost impossible to do this with modern digital cameras due to the noise found on the images.

Eclipse chasing

It is estimated that more than 20 000 people gathered in Exmouth to witness the eclipse. We chose to take the eclipse cruise that was run by P & O. Apart from not having to worry about the driving, it was a great opportunity to listen to presentations provided by a range of experts on astronomy, physics and general star gazing. Two of the most impressive presentations were given by a Year 12 student from Canberra on astrophotography. Each night we able to gather on the back deck of the ship to observe the Milky Way without light pollution.

It was fascinating to encounter people who have spent many years chasing eclipses around the world. It wasn’t unusual to speak to someone who had seen more than 15 total eclipses. At least one person had seen 29 of them. For those of us who were about to view our first solar eclipse, we were told that the first words we would speak after seeing it would be ‘when is the next one?’.

the best way to photograph the eclipse. The main recommendation was to spend more time looking rather than trying to take photos as there would be better photographs available taken by experienced photographers.

With that in mind, I still intended to take photos and spent some time before the cruise researching the best way to set up a camera. I eventually landed on taking a crop sensor camera with a 300 mm zoom lens and a solar filter sheet to create a filter for the front of the lens. The shaped solar filter sheet was taped on both sides so that it could be slipped off the front of the camera easily (Figure 2). Just as you should never look directly at the sun without a proper solar filter, a camera should never be pointed at the sun without a solar filter on the front of the lens. The only time the sun can be viewed without an appropriate filter is during a total eclipse. Similarly, for photos, the solar filters are removed during the total eclipse.

Eclipse and solar photography

Several sessions were offered on the cruise on

The colour of the sun as viewed through the camera will depend on the type of filter used. The solar filter sheet set up (Figure 2) generated yellow images of the sun. Other filters will produce white solar images.

Counting down to the eclipse

The ship was anchored by 8.00 am on the morning of 20 April. The engines were shut down to reduce the vibration in the deck. Our older daughter was out early to hold a space for us. As the ship was an older one, it had more open deck space than the newer ships, meaning everyone was able to find a good spot for viewing. Although there were over 2000 passengers and many crew out on deck, it didn’t feel crowded.

The moon commenced its crossing of the sun around 10.00 am, with the first bite out of the sun becoming visible (Figure 3).

The prominences and Bailey’s beads were visible for a moment before the corona becomes visible. As the image shows, the prominences were a deep pink colour (Figure 5).

As 11.30 am approached and the moon had almost covered the sun, service on the ship was suspended to allow as many crew members as possible to also view the eclipse.

The corona, or outer atmosphere of the sun is only visible to the eye during a total eclipse (Figure 6).

As the last sliver of sun disappeared (Figure 4), there was a roar from the crowd as the prominences and then the corona became visible. It was at this point that glasses were whipped off (as well as the filters on cameras).

This last photo (Figure 7), which was captured from a video of the eclipse shows how bright most of the sky was, even during totality. As a very short eclipse, the umbra was narrow. To the left of the corona, it is possible to make out Jupiter faintly. A longer eclipse with a larger shadow would create a much darker environment and more stars would be visible. As the shadow was narrow it was possible to observe it racing across the water towards the ship.

Totality lasted for only slightly less than a minute, but it was awe inspiring. Being able to view parts of the sun that we can’t normally see and to do it without glasses was an amazing experience.

Victoria’s perspective

Victoria, my younger daughter, is currently in Year 10. She has provided a couple of paragraphs on her impressions of the eclipse.

Once the eclipse first began, it was very difficult to see any difference in the sun, or where the moon was coming from, until after about 15 or so minutes when you were able to see a very small chunk of the sun missing while looking through the eclipse glasses. It ended up taking quite a long time, with some people leaving to do other things while waiting for the solar eclipse to get closer to totality. When the Sun was almost half covered, you could start to feel a difference in temperature and light, with it becoming slightly cooler and dimmer as the moon began to cover the sun. Reaching closer to totality, the sky began to dim much faster, though the shadows became rather sharp and distinct.

When the moon finally completely covered the sun, it was a very quick difference, with the sky darkening to the point it appeared that the sun had set an hour or so prior. The sun was no longer visible through the eclipse glasses except for maybe a slight ring around the moon. Looking without it, the sun was replaced with a pure black circle, surrounded by a ring of white light that stretched out a little bit, somewhat reminding me of depictions of black holes. Many pictures that I saw after did not show just how far out the white ring stretched.

Despite how long it took for the eclipse to reach totality, it only lasted about a minute, though it was fully worth the wait to see such a rare and spectacular view.

In conclusion

As totality slipped away, our first words were indeed, ‘when is the next one?’. For Australia, the next total eclipse will be 22 July 2028. This eclipse will run from just out of Kununurra, all the way across the country to Sydney with totality expected to last between five and seven minutes. We are already planning.

References

1. Map of eclipse path for April 2023. Accessed 5 June, 2023 https://www.timeanddate.com/ eclipse/map/2023-april-20

2. Thousands in awe as solar eclipse hits totality over the skies of northern Western Australia. Accessed 5 June 2023. https://www.abc. net.au/news/2023-04-20/total-solar-eclipsevisitors-seek-best-view-totality-exmouthwa/102242192

3. Accessed 10 June 2023 File:Eclipses solares. en.png - Wikimedia Commons Copyright: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/ File:Eclipses_solares.en.png

4. Eddington Experiment. Accessed 30 May 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eddington_ experiment

5. Robins, John L History of the Department of Physics at UWA, Issue 9, p 1 - 9 https:// www.physics.uwa.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_ file/0014/621122/PhysHist9.pdf#:~:text=In%20 1922%20an%20expedition%20was%20 undertaken%20to%20obtain,to%20test%20 Einstein%E2%80%99s%20newly%20 proposed%20Theory%20of%20Relativity.

6. All of the photographs were taken by the Authors.