10 minute read

The History of Thanksgiving

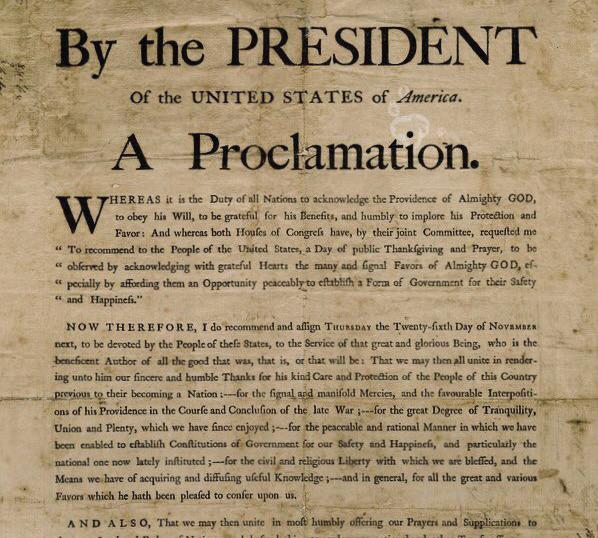

The original Thanksgiving proclamation was published in The Massachusetts Centinel on Oct. 14, 1789. (Photo courtesy of mountvernon.org)

___ By Garrett Cote ___ @garrett_cote

Advertisement

The beloved holiday of Thanksgiving -- a day of tradition and four ‘F’s’: family, friends, food and fun -- returns again on the final Thursday of November, as it always does. But this year, while peering down at a plate full of turkey, stuffing and mashed potatoes covered in a thick coat of gravy, try to urge a thought back to the events that unraveled to allow such a wonderful annual practice.

Long ago, in November of 1621, a group of 53 pilgrims gathered for a feast. Four men were dispatched to hunt and kill as much fowl and deer as feasible to satisfy this group for an entire week. The only known recollection of this event, now considered the first-ever Thanksgiving, was registered and inscribed in writings by two primary sources: Edward Winslow in Mourt’s Relation and William Bradford in Of Plymouth Plantation.

More than 150 years later, United States President George Washington issued a document, known as the Thanksgiving Proclamation of 1789. It’s unclear if the House of Congress knew of the original gathering in 1621 (it was not mentioned in the proclamation) when it urged Washington to distribute this letter to the American people -- recognizing the protective care of God as a spiritual power. Washington wrote, “Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly to implore his protection and favor-- and whereas both Houses of Congress have by their joint Committee requested me to recommend to the People of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer…” “Now therefore I do recommend and assign Thursday the 26th day of November next to be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious

History of Thanksgiving

With Thanksgiving just a week away, The Student takes a look at how this foodfilled family holiday came about.

Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be…”

Washington’s vision of a day dedicated to Thanksgiving was sparked because of the Revolutionary War, and he claimed the importance of this day came from God’s care of Americans prior to this Revolution, helping them strive for their goal of reaching independence. The day, in essence, was a way to come together with family and friends to appreciate the simplicities of life during troubled times.

Years after Washington’s proclamation, President Abraham Lincoln revisited the first POTUS’s Thanksgiving order in 1863 -- in the middle of the Civil War. Lincoln sought a way to heal a divided country, thus generating a second pact of Thanksgiving.

This would set aside the last Thursday of November “as a day of Thanksgiving and Praise,” according to one of Lincoln’s secretaries.

“Each state celebrated Thanksgiving on a different day prior to Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation,” said Springfield College history professor Thomas Carty. “Acting during the Civil War, Lincoln hoped that a uniform national holiday would help unite the country in troubled times. He made a proclamation saying that we’re going to commemorate this day. He was looking for a way to unify the country after the internal killing, tensions and bitterness of the Civil War.”

Lincoln’s proclamation had a wave of energy behind it, and with that came great success. The country desperately desired some form of light in a dark time, and the American people bought in. For good.

Because 1863 was north of a century and a half ago, Thanksgiving has evolved and expanded with time. What started as an American-only holiday has ventured off into an abundance of different cultures, consequently, giving rise to many different approaches to celebration.

“Thanksgiving is a unique American holiday, and we associate it with unique American sports like football games,” said Carty. “But like a lot of U.S. holidays, it has grown so much. In some ways due to marketing and globalization, and in some ways due to consumer culture. Now many different cultures celebrate it in a variety of ways.”

On Thanksgiving, it’s important to understand and address the Native American peoples who were dismissed from this very land in the most gruesome of ways.

“Thanksgiving should remind us to recognize the sacrifices of many Native American peoples who suffered disease, exploitation, and removal during these centuries following English arrival,” said Carty.

In 2021, after a long two-year hiatus from normal Thanksgiving glee (considering the majority of states heavily advised against large gatherings), this year has an eerily similar feeling to what Lincoln mentioned in his proclamation. After an unimaginably long bout with the COVID-19 pandemic (while it is still far from over) and the burdensome task of switching back to in-person courses this semester, this many families will finally resume treasured rituals, and Thanksgiving will once again provide a much needed sense of togetherness as it has in centuries past.

Newfound passion for change

Springfield College senior Luther Wade plans to implement his new passion for social justice in his future career as an educator to help change the perspective on Black people in America.

Luther Wade helped organize the first protest on Alden Street since 1970. (Joe Arruda/The Student)

_ By Collin Atwood _ @collinatwood17

On June 14, 2020, the small suburban town of Waterford, Connecticut was the home to a protest where 600 people marched in the names of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and the many others who are subjected to the harsh injustices of this country.

The crowd marched for two miles on the roads of Clark Lane, Boston Post Road and Rope Cherry Road which is where the town’s high school is located. The protestors even received help from the local police department as they blocked off roads so that this march could take place.

None of it would have been possible if it weren’t for Luther Wade, a senior at Springfield College studying physical education.

Wade attended Waterford High and throughout his four years there he never thought about anything other than sports. As a three-sport athlete, his time was mostly consumed with practice and working out. There wasn’t enough time in his schedule for other extracurricular activities.

It wasn’t until Wade arrived on Alden Street that his mindset would change from focusing on sports to social justice.

Wade came to Springfield with an interest in pursuing a career in athletic training, but that passion quickly diminished. He didn’t love the responsibilities of an athletic trainer enough to let it take up that much of his time.

“I was kind of falling out of love with it,” Wade explained, “I wasn’t as good at it as I thought I was going to be and adjusting and learning in the classes and just being in the environment just wasn’t something that I wanted to do anymore.”

Wade decided to switch his major to physical education and that gave him more time to join clubs on campus. The first club he joined was Men of Excellence which is a club that empowers men to be the best versions of themselves.

When Wade first found out about Men of Excellence he was scared to attend a meeting after being invited by Marcel Diaz, former secretary of Men of Excellence.

“I didn’t necessarily want to go at first. I was scared and I didn’t really want to be there by myself and put myself out there,” Wade said. After being convinced by his roommate, he decided to get involved in the meetings.

Ever since that point, Wade has been a part of many important and even historical events on campus pertaining to social justice. In Oct. of 2020, Wade hosted a SEAT at

Wade led the March for Action with organized chants and a walk around campus. (Joe Arruda/The Student)

The Table event where he talked about the use of the N-word. Shortly before that, he and other student leaders organized The March on Alden Street which was the first protest on campus since 1970.

His leadership abilities and commitment to changing the campus climate got him voted as the President of Men of Excellence, something he never envisioned happening.

“Once I joined and went to the first meeting I knew I was going to go for the rest of the time that I was at school,” he said. “But I didn’t necessarily picture myself leading the club because when I first came I didn’t see myself as a leader.”

He obtained a lot of leadership skills by learning from the members of Men of Excellence and attending meetings and events.

“Being in that space and learning from so many people that look like me and experienced the same difficulties was cool and it was empowering because I never got that and that’s kind of what I was looking for,” Wade said.

These are the skills he plans on using, along with his physical education degree, to educate and coach high school students after graduation.

One of the other reasons Wade switched majors was because he realized it was important to him to be a service to other people and to help change the perspective of Black men in America.

“It just became prevalent to me that people should be treated the way they should be treated because they’re a person and we’re all people,” Wade said.

As a Black man who grew up in a predominantly white neighborhood, Wade understands what it’s like to be judged and perceived as something different than who he actually is. “I’ve been held to prejudices and I’ve been racially profiled by the police,” Wade said.

He thought that it was possible to implement change through athletic training, but believes teaching will make it easier to leave an impact on students.

“I realized that through teaching and being in the classroom with these students and having that allotted time where you have their attention and they’re supposed to be learning from something that you planned, I feel like that’s where I can do the most and change the most,” Wade said.

In Wade’s high school there was only one Black faculty member and he wasn’t an educator. Wade refers to Kevin Blackburn, his high school security guard, as his “safe haven.”

“He cared about me and looked out for me...I was in the suburbs so he was legit the only one,” Wade said.

That high school on Rope Cherry Road is exactly where Wade returned to for the walk he led back in June of 2020. It was time for Wade to share his newfound passion with his hometown. Wade, with help from his hometown friends, was able to organize a walk, speeches and demands for the education system in Waterford.

“It was good for our community to hear what was said at the walk...we just talked and shared our experiences with what we had in the town and how those problems are relevant and premilent in our town.”

Some of the demands included hiring more staff of color and making students take an African American history class, demands that are similar to the ones made at Springfield College just months later.

“It was a good day and I think only good outcomes are going to come from that.”

Just four years ago, Wade wasn’t even thinking about being a leader on campus or in his community. Years later, he found himself leading crowds of people through his old community and new, chanting through his megaphone as hundreds of people repeated.

The people of Alden Street and Rope Cherry Road have reaped the benefits of Wade and his leadership. Only time will tell what community, or street, will be next.