6 minute read

Getting her due at long last

Nancy Edwards was prohibited from competing in collegiate tennis even after dominating on the Marietta men’s team. Now, 60 years later, Edwards is finally receiving the recognition she earned and deserves.

___ By Patrick Fergus @Fergus5Fergus

Advertisement

Good things are worth waiting for.

Nancy Edwards has waited 60 years to receive her varsity letter from her alma mater, Marietta College in Ohio. In the coming weeks, as a part of the yearlong celebration of the 50th Anniversary of Title IX, the former varsity tennis player will do just that.

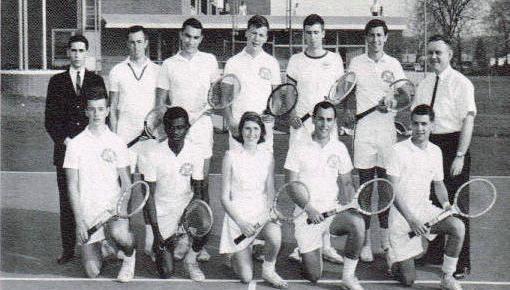

Edwards, formerly known as Nancy Devlin, attended Marietta from the fall of 1962 to 1966 and was one of the first women to play on a men’s varsity team. The men’s tennis team captain noticed Devlin when she was playing a casual game with her friends and insisted to the coach that she be on the team.

The coach agreed on one condition. Edwards had to endure and pass a physical, which was no easy task. She had to run up and down the stairs of the Ban Johnson Arena 50 times, which Edwards recalls as “almost killing her.”

When she finally got out onto the court, she was nothing if not impressive – winning each of her first three matches with the help of a strong serve and great forehand. According to Edwards, her team- mates and coaches readily welcomed her to the team and never treated her as any different because of her gender.

The opponents’ coaches felt different, however, pointing to an obscure section in the charter of Marietta, which clearly stated that tennis was “for all bonafide male undergraduates.” In other words, they did not like their players being bested by a woman. Marietta never had a problem with a woman playing on the men’s team. However, the NCAA and its other members did not want the genders to mix. As a result, Edwards’s time on the team came to an abrupt end.

“Some other colleges said I could play, but no matter the result it would count as a loss,” Edwards said. “I wasn’t at all surprised. This wasn’t the first time this had happened.”

Certainly, the lack of shock and frustration could be attributed to her personal history, as she had a similar experience at Dartmouth (Mass.) High School. She also played against boys in high school, but opposing coaches were upset with her continued success, and barred her from competing.

Back at Marietta, Edwards was very surprised by the amount of attention that the story was receiving. The Associated Press had gotten wind of her departure from the team, and soon more and more newspapers were calling Edwards on the dormitory telephone, mixed in with the occasional fan letter.

“I was really too young, and didn’t know how to han dle all of this fuss,” Edwards said.

The director of women’s athletics offered Edwards the opportunity to teach lessons and even start her own wom en’s club team. She liked teaching people how to play, but ran into a lot of prob lems when it came to putting together a squad.

“I didn’t real ly receive a lot of support or funding, and it just didn’t seem like they were taking it seriously, which was definitely a source of frustra tion.” Edwards said.

Despite her play﹣ ing career being al most 10 years before the passing of Title IX, Edwards’s story is the epitome of why the law was cre ated –as an amend ment that prohibits discrimination based on sex in educational programs and activ ities funded by the federal government.

Edwards graduat ed a semester early from Marietta with a Bachelor in Science, and now lives in a small community called Nonquitt in Dartmouth, Mass.

“Looking back, I think I should’ve tried making a big ger deal for women’s sports, and I didn’t want to cause any problems for the university by mak ing it an issue….but I really wish I was more responsive,” Edwards said.

Now, 60 years lat er, Edwards will fi﹣ nally return to cam pus for the first time since her graduation.

Along with about 10 other female athletes who never acquired their varsity letters, Edwards will at last collect her varsi ty letter ﹣ belated validation of her outstanding accom plishments on the court.

Larry Hiser, the Director of Athlet﹣ ics and Recreation at Marietta, who also received his masters degree in science for physical education and athletic adminis tration at Springfield College, is excited to welcome Edwards and other former female athletes back to the school.

“The Title IX Committee devised this great idea, to give letters to all those women who would’ve qualified for them, if the proper system had been in place,” Hiser said.

Hiser also had the pleasure of speaking to Edwards, after she called to thank him for the invi﹣ tation and for the letter.

“She was the easi est acquaintance I’ve ever made,” Hiser said. “Her story is completely emblem atic of Title IX. I mean, you can’t have Hollywood make a better one.”

The event needs a spokesperson, and to Hiser, there was no better fit than Ed wards and her sto﹣ ry. Even with some hesitation about speaking in front of so many people,

Edwards happily agreed.

The celebration is very meaningful for the women that are returning to receive their honor. One of them told Hiser, “When I get that letter, I will put it up on my mantle. I will feel for the first time that I belong in Ban Johnson Arena.”

Back in Non quitt, Edwards, 78, still plays tennis . Thanks to a regu﹣ lar Saturday men’s group and mixed doubles, her com petitive spirit and love for the game of tennis has never wavered.

“Yeah, I’m still playing, which I just love,” Edwards said.

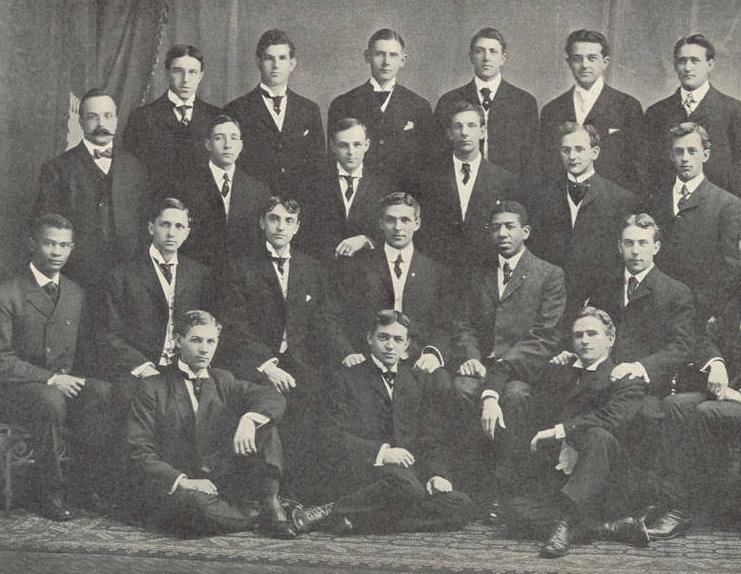

BHM continued from Page 3 was at T.S., he seemed to be involved and friendly with the other students, despite the racial barrier. Beckett was mentioned many times to be a great musician. In a poem in which each student of the graduating class was given a stanza, Beckett’s read: “Could Beckett play the piano?/ Why, man, you know full well/ You couldn’t control your tingling toe/ He played so mighty well!”

Beckett had a long and impressive career following his years at T.S. He went on to work at the Y.M.C.A. in Washington, D.C., as first the physical director and then the executive secretary. In 1917, he served the United States Army in World War I, and was discharged a year later.

His next step was Sumner High School in St. Louis, Missouri. It was here that Beckett helped change the lives of many young people.

“He was a builder of men first and a coach second, as he trained the many boys how to take care of themselves in life,” stated an article about Beckett in the St. Louis Argus newspaper, written when he was being honored at the 75th anniversary of Sumner High School.

Beckett used his position as the football coach to bring the ideals of T.S. into other communities, helping to support young Black men during a time when they didn’t receive much support from anyone else.

The final words of the article read: “In closing this brief story, I am hoping that I will see all of the members of the old school in the stands Saturday night when they honor ‘Pops’. That stadium should be full, so full that when he looks up, tears will roll down his cheeks in sheer happiness.”

Beckett also introduced basketball to Sumner High School and the St. Louis area, the sport that was famously created at Springfield College.

He was an advocate for athletics and helped to build up the skill on and off the field and court for the students he taught.

Later on in his life, Beckett became one of the founders of the oldest Black conference in the nation: the Colored Intercollegiate Athletic Association. It has now become the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association, which includes 12 institutions that compete in NCAA Division II athletics.

The CIAA gave Black universities the opportunity to compete at a higher level, something that was not an option prior. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, the CIAA continued to be segregated and received little attention from white popularized media, however member schools continued building up the conference to make a name for itself. Without Beckett, the CIAA wouldn’t have happened when it did, allowing the young Black men he was coaching at the high school level a chance to now go on and play competitively in college.

Beckett proved his work to be important and was seen by the greater community when in 1947 he received the Tarbell Medallion Award from Springfield College.

The Tarbell Medallion began in 1934 and still exists today, honoring alumni who “demonstrated varied outstanding service over a period of time to his or her alma mater… have also demonstrated dedication to the Humanics philosophy.” This prestigious award honored Beckett for the work he did in the Midwest while supporting Springfield College and spreading its ideals around the country.

Beckett died in 1954, the same year of the Brown v. Board of Education ruling during the rise of the Civil Rights Movement. Throughout his lifetime, he experienced a world where some thought he was unworthy simply for the color of his skin.

During a time when society rejected Black people and pushed them to the outside, Beckett broke through. He made a difference in the lives of Black youth and did so through the Humanics qualities he learned at the “old T.S.” The Training School would go on to become Springfield College; with a philosophy preaching service to others, Beckett characterized what the school stood for before it became tradition. The history of what Beckett did for the school is so much more than his one line credit in the College’s timeline.