4 minute read

SOARING

Artist Hebru Brantley’s Chicago-born vision has resonated far beyond his home turf—and this could be just the beginning.

By Matt Lee

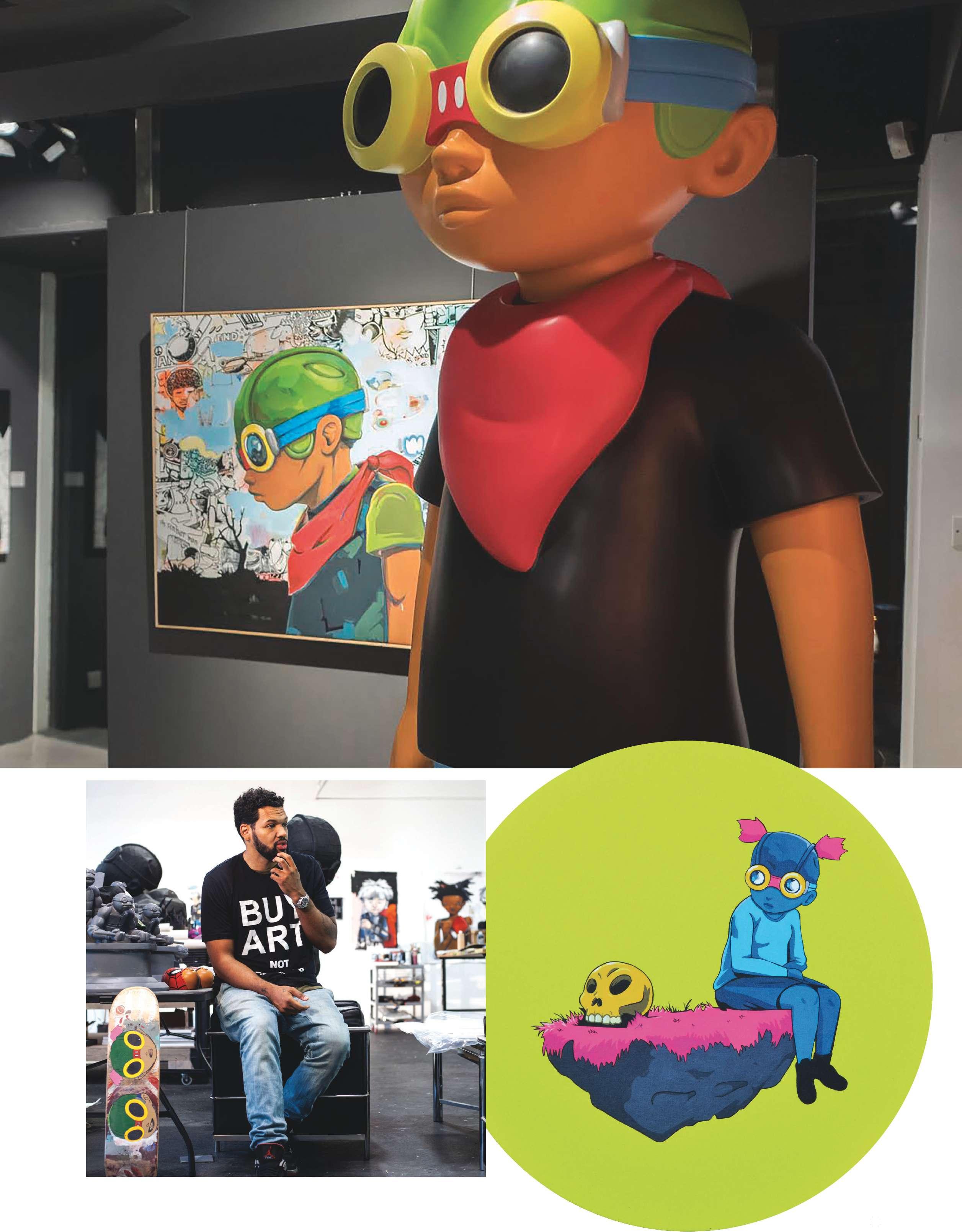

It’s the goggles. Or maybe it’s the vintage WWII-era pilot’s cap, coupled with the handkerchief. Or, maybe, it’s the sheer momentum of the character, flying forward. Whatever it is, once you see Chicago artist Hebru Brantley’s Flyboy character, you remember him.

Top: Exhibition photo from the solo exhibition “Lord of the Flys” at Avenue des Arts gallery, Hong Kong Photo by Cyril Delettre Bottom left: Hebru Brantley in studio, Chicago Portrait by Frank Ishman Bottom right: Island 2 mixed media on canvas from the “Lord of the Flys” series (20” x 20”), 2017 Photo by Bianca Griffin

These days, likely more Chicagoans than not recognize Flyboy. Inspired by the Tuskegee Airmen, Flyboy has adorned murals from Bucktown to Uptown to the South Loop and, in 2016, was the inspiration for a Chance the Rapper video viewed by almost 20 million people. While he’s no doubt Brantley’s signature character, though, he’s far from the only one—and the scope of the artist’s work is sprawling, in more ways than one.

Like other creative pioneers, Brantley has made not just a remarkable career, but a remarkable life, out of doing what he loves. That’s far from a platitude. An artist since he was a child on the South Side, Brantley has produced a body of work influenced by phenomena ranging from comic books and cartoons to Jean-Michel Basquiat and anime. This amalgamation of influences isn’t a quirky-sounding bio sound bite, but rather the uniquely disparate components of Brantley’s vision—simply put, what he had, by hook or by crook, to get out into the world.

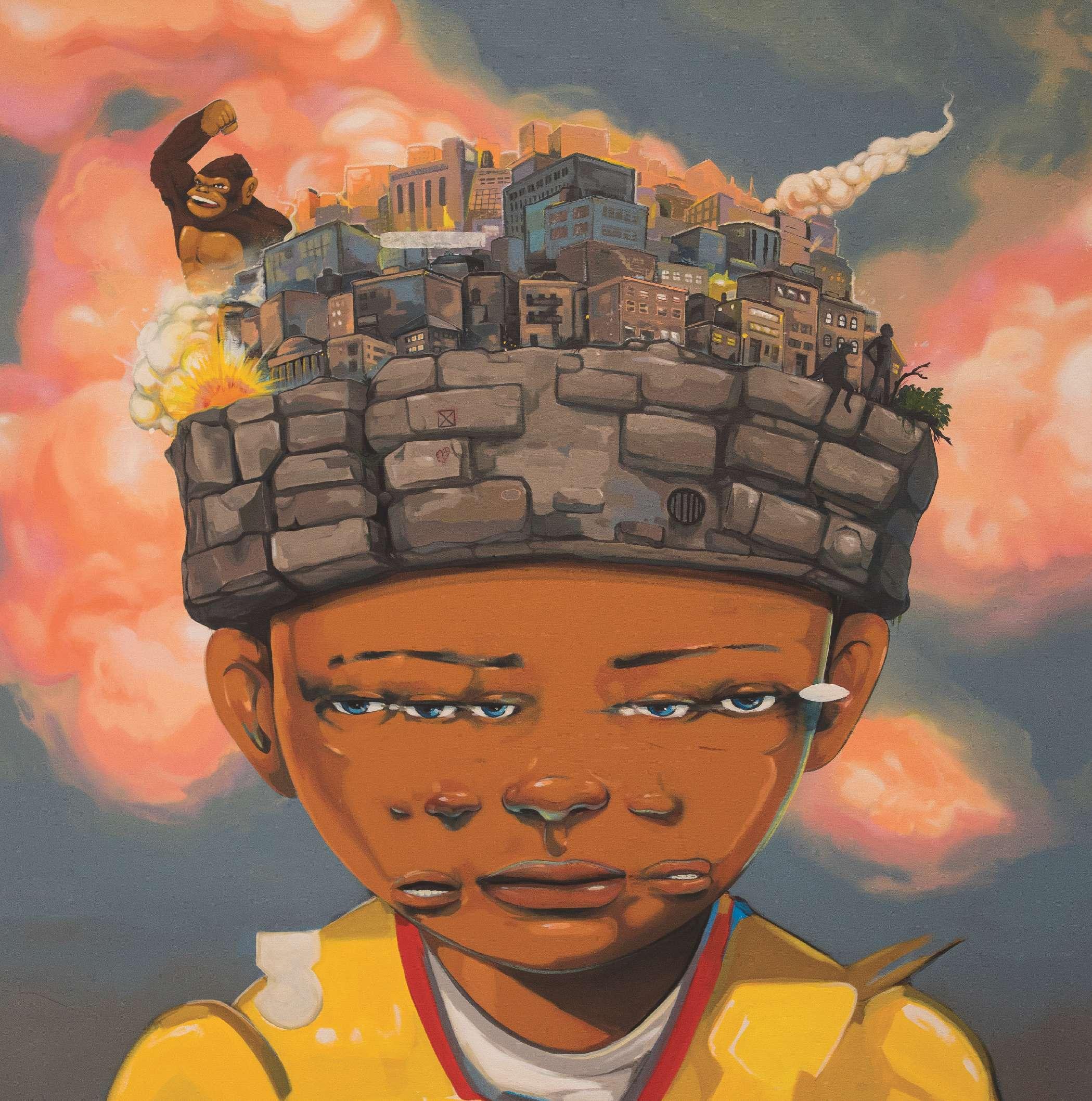

Futr Futur mixed media on canvas from the “Lord of the Flys” series (36” x 36”), 2017. Photo by Bianca Griffin

Brantley’s story is a Chicago story, though, and first of his influences among equals is the Chicago-based AfriCOBRA street art movement of the 1960s and ’70s. “It was all around me,” says Brantley, who splits his time between Chicago and L.A., but calls Chicago home. “That was my daily journey to the crib. You pass by those walls, those murals… In my limited exposure growing up, that’s what I was exposed to and what I understood to be art or street art.”

He didn’t take an art class in high school, but while studying film at Clark Atlanta University, he found the art classes he snuck into at the Art Institute of Atlanta more compelling than his chosen field of study. After graduation, in 2002, while painting on the side and working at a record company, he sold his first painting to a DJ friend. It was then, he says, he considered becoming a professional artist. His vision, ultimately, coalesced into what can be described as character-driven narrative art.

Brantley’s work is wide-ranging, however, spanning a wide variety of media and subjects. Recent pieces alone have addressed such diverse topics as the relationship between Basquiat and Andy Warhol and, in an ongoing series of reimagined comic book characters, Captain America and Batman and Robin.

His take on these subjects has resonated, and his career has soared like Flyboy. Among many other high-profile venues, Brantley has exhibited at Miami Art Basel, Scope NYC and Frieze London. Celebrities like Jay-Z and Beyoncé, George Lucas, LeBron James and Nicki Minaj count themselves as collectors of his work, and he’s collaborated with everyone from Jordan Brand and Hublot to Nike and Nickelodeon. In 2016, Flyboy took what in some ways was his greatest flight yet, as Brantley teamed up with another Chicago mega-creative, Chance the Rapper, on the Flyboy-inspired video for “Angels,” viewed almost 20 million times on YouTube.

“I know a few people,” Brantley says when asked about his relationships with Chicago musicians, from Chance to Lupe Fiasco. And the city, he says, is a more friendly place for creatives of all stripes than it once was. “My feeling on Chicago is a fondness,” he says. “Especially when I leave and come back. A lot of that has to do with age. When you’re younger, you might not appreciate certain things like you would when you get older. Chicago is a great place. I love that it’s able to cultivate young talent in the arts now. I don’t feel that it always did.”

Crown of the Metropolis Pt. 6 (Tale of a Future Mogul) mixed media on canvas from Brantley’s “Forced Field” solo exhibition at Elmhurst Art Museum, 2017 Photo by Anthony Trevino

Whether here or elsewhere, Brantley can usually be found working. “It’s pretty boring, man,” he says, discussing his typical day. “I’m in the studio around 8 in the morning, working until around 6 PM. I come home to spend some time with my family and then, normally, I’m back in the studio about 9 PM and work for a couple more hours after that. Live, die, repeat. Live, die, repeat.” When he does have free time, he can be found at a few favorite spots around his neighborhood, including Dusek’s, Punch House, or Soho House Chicago.

Despite his herculean work ethic, Brantley has little in common with the stereotype of a reclusive artist content to toil away in obscurity. On the contrary, he sees himself in the mold of Walt Disney—with Flyboy as his Mickey Mouse. To be sure, the world is his oyster: Beginning in October, Brantley will be showing his latest works at Avenue des Arts in L.A. And while he couldn’t go on record about other upcoming collaborations and exhibitions, suffice it to say that Flyboy could soon be known on a far larger scale.

“Everything’s part of a plan,” he says of his illustrious career, weighing strategy versus spontaneity. “You have ideas and go forth and execute, then other things come in. Great things happen that you didn’t necessarily plan for, and other opportunities come about. But it’s all been a plan.”

The magical moments are mostly born of sweat. “It all depends on the context,” he says, looking back at the highlights— so far—of a career filled with too many of them to count. “It’s hard to quantify. It’s a lot more about the little moments than the bigger ones people might assume. There are a lot more of the smaller moments that leader to the bigger moments."