72 minute read

Obituaries

The following alumnae have died very recently and we plan to include their full obituaries in next year’s College Report : April Carter, Katherine Duncan-Jones, Joyce Reynolds, Rosslyn Green and Miriam Webber.

Sarah Broadie (Waterlow, 1960; Honorary Fellow 2005)

Sarah Broadie (1960, Lit. Hum.) had a distinguished career as a teacher of ancient philosophy and author of influential books on Aristotle and Plato. Her academic career after Oxford began in Edinburgh, where she married Frederick Broadie, and continued at various US universities including Yale. In 2001 she took up a prestigious position at St Andrews, where she remained, active in teaching and writing, until her death in 2021. She was much loved and sought after as a teacher and lecturer both in the US, where her distinctive voice marked her as an old-world scholar, and in the UK. Honours were heaped on her: a Fellow of the British Academy, she was made an Honorary Fellow of Somerville, and awarded an OBE in 2017.

Sarah retained an affection for Somerville and gratitude to her teachers: Mildred Taylor to whose memory she dedicated one of her books, and her philosophy tutors Miss Anscombe and Mrs Foot. Invited to speak at the memorial symposium for Philippa Foot, Sarah gave a talk on Aristotle on Practical Truth, inspired by a famous article on the subject by Elizabeth Anscombe. Generations of students and scholars have benefited from her most successful book Ethics with Aristotle (Oxford, 1991).

Lesley Brown, Emeritus Fellow

Remembering Sarah Broadie

At Somerville we were a group of five friends. Sally Waterlow was the one who brought a philosophical slant to our conversations, once getting us to experiment being completely honest in everything we said (we ended up skewering each other); another time wanting us to discuss how we knew that dogs couldn’t read. She had a wild sense of humour, and a fund of silly songs from between the wars – I can still hear her voice, with its very characteristic upper-class timbre, singing ‘Button up your overcoat when the wind blows free. / Take good care of yourself, you belong to me …’.

I remember visits to her parents’ country house in Wiltshire, and her parents: John, a distinguished medic, who cultivated a flourishing midden derived from the family’s earth closet, and Angela, a gentle, affectionate woman and a passionate painter.

SARAH BROADIE

to a museum curator, who retaliated with the same speech pronounced as modern Greek – each was incomprehensible to the other. At one point she insisted on carrying my travel bag as well as hers, claiming that it was easier to be weighted down on both sides. This was characteristic of her as a friend: she was very keen to shoulder others’ burdens, sometimes literally. I remember, too, us riding up Mount Olympus on donkeys, fighting off predatory Greeks (Sally once striking an importunate museum attendant with our copy of the Blue Guide), hitching and sleeping rough, and coming back feeling we had been wildly adventurous.

She had been very standoffish with a number of admirers, but then in her final undergraduate year I remember her philosophical romance with an American philosophy postgraduate, Loren, who was quirky and fun. He once summoned me to ‘come and quiddify’ with them, and another time infuriated the head waiter at the Elizabeth restaurant by whisking out a collection of toy cars and getting his guests to zoom them noisily across the table. When the relationship didn’t work out, they decided to try marriage to see if that would help. It didn’t and they split up almost at once.

I remember the damp flat along the canal which we then shared as graduate students. Typically, she insisted on my having the big main room, which was also our sitting room, while she inhabited a tiny back room – she said she needed privacy, but I felt it was more like privation. We had our circle of new, younger friends: Marina Warner, Emma Rothschild, Tim Jeal and others.

When she was a university lecturer in Edinburgh, I went there to meet her much older husband and fellow philosopher, Frederick, who played the violin, and her immature but full-sized great Dane called Dandy, who insisted on sitting on my knee.

Later, as she was promoted, she and Frederick settled in the USA, and later still, back in Britain, they lived miles away in Scotland. But we kept in touch. On her last ever visit to London we shared an Indian curry, and in her final months we used to talk regularly on the phone, long conversations, mostly about books. As always, she made me feel on my mettle not to allow myself sloppy comments or lazy thoughts. She was an intense reader of fiction, with idiosyncratic tastes (I particularly remember Sybille Bedford, Theodor Fontane). She would buy all the works of a writer she admired and binge-read them avidly. More recently, I admired her stoical acceptance of her failing lungs, which handicapped her so badly that she spent her days in bed. And I vividly remember our last conversation – her book on Aristotle had just come out, and she said calmly that she would be unlikely to write anything more. Her mind was fizzing as always, and our conversations were so thrilling that I find it hard to remember that she has died.

Maya Slater (Bradshaw, 1961)

Derek Goldrei (Somerville Lecturer in Mathematics, 1978-2003)

Derek Goldrei died unexpectedly on 2 July 2022 – his 74th birthday.

Derek’s real job was at the Open University where he spent his whole career, but each Thursday in term time he would descend from Boars Hill to Somerville for lunch followed by an afternoon of tutorials. His tutorials were much appreciated and enjoyed and gales of laughter could often be heard coming from House 10. He got to know the undergraduates he taught well and offered wise guidance to many over the years. He loved teaching and conveying his own enthusiasm for mathematics and, although he was able to devote himself to teaching at the OU, he appreciated this chance to meet real students regularly.

In 1978, when Jane Bridge, Somerville’s tutor in pure maths, married and moved to the USA, Derek came to our rescue. He took over a large part of Jane’s teaching and the organisation of the maths school for the year 1978-79 while her successor was appointed, and fortunately we were able to persuade him to continue, with a reduced load, for the next 25 years.

Derek’s connection to Somerville went back even earlier. His sister Diane had been an undergraduate at Somerville, and when he came up to Magdalen in 1967 he spent a lot of time in Somerville where he made many friends. When the JCR first set up a bar in the Reading Room, Derek was a regular barman and his congeniality did much to make this venture a success. He stayed on in Oxford to do a DPhil in Logic under the supervision of Robin Gandy, thus following in Jane Bridge’s footsteps, before going to work at the OU.

Derek was a larger-than-life character both physically and in the social activity that was generated around him. He made friends with many members of the SCR and impacted on a whole generation of Somerville maths undergraduates. In 2003 he moved to Mansfield College where he was made a Fellow and continued to teach undergraduates until he retired.

DEREK GOLDREI

Hilary Ockendon, Emeritus Fellow

Jean Velecky (Stanier, 1941)

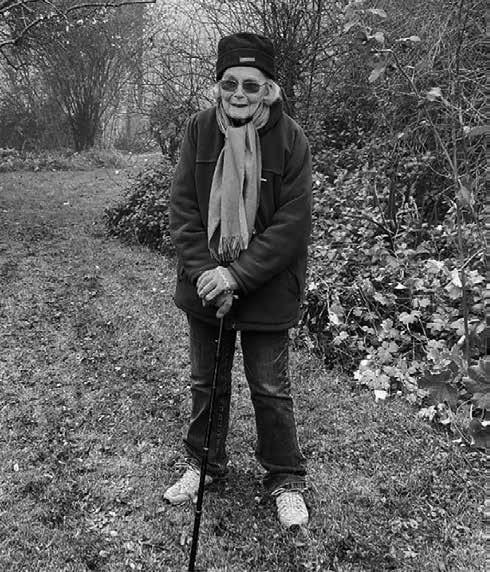

Jean Velecky died on 6 March 2022, at the age of 99. With the help of her wonderful neighbours, carers and family she was able to live at home until the end, as Jean had hoped would be possible.

Born in Victoria, British Columbia, while her parents were living there, Jean was the youngest of four children. They returned to Britain when she was two, and lived in Hythe before moving to Winchester. Jean was educated at home by her mother using the PNEU system until she was eight, and then moved on to St Swithun’s in Winchester, where she was very happy.

Jean won a scholarship to study Natural Science at Somerville in 1941. During war-time, degrees did not follow the usual pattern; Jean studied Natural Science 1941-43 and Physiology 1945-46, being awarded her BA in 1944 and MA in 1948.

JEAN VELECKY

She thoroughly enjoyed her time in Oxford, and as well as her studies she took part in sports including cricket and lacrosse, becoming a Double Blue.

From 1943-45 she worked at the National Institute for Research in Dairying. She was at the Biochemistry Department in Oxford with a Medical Research Council grant 1950-52, receiving her DPhil in 1950. She worked in a team studying under-nutrition after the Second World War in Wuppertal, Germany, investigating the volume and composition of the milk of mothers in Wuppertal and comparing it with that of mothers in different situations. Her other research work included mucoproteins, in the Biochemistry Department at Oxford, and hyaluronic acid in cattle knees, at the Medical Research Centre in Harwell. Later she moved to Southampton University where she researched the hepatopancreas of crabs.

She left her academic career in 1965 when she married Lubor Velecky, whom she had met playing recorders in Oxford. Playing recorders in small groups remained a pleasure throughout her life. Together they made their life in Southampton, where they raised their family and were both very involved with the local community. Among other local activities Jean was much involved in Southampton Commons and Parks Protection Society, the Friends of Southampton Old Cemetery and stewarding at St Michael’s Church Southampton. She also ran activities for Girl Guides and Brownies, including many Guide camps; she volunteered in the resources centre at a primary school, and she read to children in the children’s ward at the hospital. Jean helped the local orienteering group in many ways, having acquired an interest in orienteering from Lubor. Orienteering formed a large part of their life, Jean continuing into her 90s, representing England as a veteran and winning many national trophies. Jean was modest and unassuming and a hugely loved member of her family. She is survived by her two children, Alan and Sarah, and by five grandchildren.

PATRICIA BEESLEY, OCTOBER 2021

Ruth Stanier, niece

Patricia Beesley (Mears, 1945)

Pat and I came up in 1945 to a heady Oxford mix of straightfrom-school and just-back-from-war-service. It was Janet Vaughan’s first year as Principal, with few ex-service Somervillians but the next year they arrived in force.

Vacations started in Sartre’s Paris where bread was still maize yellow and coffee chicory-flavoured dandelion extract, the comparative luxury of Switzerland for German language learning, and back through Strasbourg, now made French again, where tram signs read ‘Parler français, c’est chic’ and women were washing their clothes in the river. That was postwar Europe.

Armed with her degree in French and German and a six-month secretarial course, in 1949 Pat went to the newly-formed Council of Europe in Strasbourg. There she met Hugh Beesley, whose national service had been as a navigator in the Royal Navy, then a senior scholar at Cambridge. His brother, Alan Beesley, had been one of the foremost names in post-war Oxford, with his friend, the sunburst Kenneth Peacock Tynan.

Pat and Hugh were married in 1951 by the British Ambassador in Paris and returned to a buzzing Council of Europe, now the principal meeting place for top European politicians. Miraculously they were adopted by a sought-after Hungarian cook, Mme Bonnar, who knocked on their door saying she would like to work for a young couple.

LALAGE BOWN

Thus started their semi-diplomatic life, entertaining visiting delegates as well as friends. Pat, an only child, always had a gift for friendship, her friends coming to encircle the globe. Their three children were educated in Strasbourg, later London and Paris.

The formation in 1958 of the European Economic Commission with its Council of Ministers meant that much European political power moved to Brussels. The Council of Europe, however, with its wide membership rising to 47 states, kept a significant place.

Hugh’s application to join the Commission, with an equally able colleague, both brilliant linguists, was rejected by a British recruitment wary of too European an outlook. Hugh retired as Council of Europe Director of Information in 1987.

Having long had a coastal holiday house in the Portuguese Algarve, they built there, above the golf course in a new upmarket development, Quinta do Lago. Both were keen on golf. They travelled widely: Australia, India, China, Alaska. Hugh’s knowledgeable interests ranged from art, music and science to theatre and good food and wine, many of which Pat shared. Hugh died in 1995.

After Hugh’s death, Pat set up a two-centre life in well-placed flats in London and near Quinta. Later she was joined by Bob Weeks, a friend from Oxford days, now a retired and widowed Cardiff neurosurgeon. They had twenty happy years together until Bob’s death in 2018.

Pat moved to an English retirement home near a daughter above Faro where she died on 31 December 2021. Pat’s family are spread through Germany, Switzerland, Portugal, France, Belgium, Norway and the UK. Truly European. Professor Lalage Bown, a well-loved member of the Somerville community and a notable advocate for global Adult Education and in particular women’s literacy, was born in Croydon on 23 May 1927, the eldest of four children. Her unusual name derives from an ode by Horace. Her father, Arthur Mervyn Bown, was in the Indian Civil Service, working in the then Burma. She saw little of her parents and was educated at Wycombe Abbey and Cheltenham Ladies’ College, coming up to Somerville in 1945 to read History. She subsequently did a graduate course in adult education and economic development.

1945 was still a time of austerity in Somerville, as recalled by Lalage when describing entering college under the arch: ‘There wasn’t a garden at all, but an ugly quadrangular, black-edged tank of brownish water. It was apparently originally there to help the fire-fighters in case of war-time incendiary bombs. We frivolous undergraduates said it was where the Bursar kept the baby whales to feed us, as whale-meat did turn up on her menus.’

Lalage spent much of her career in Africa, starting in Ghana (the then Gold Coast) in 1948. There, even at the age of only 22, she questioned the department’s Britishliterature-oriented curriculum, believing that authors such as Wordsworth had little meaning for Africans; she wanted them to read works by and about Africans. Her superiors doubted such works existed but she bet them a bottle of beer that she could produce numerous examples from the previous 200 years; she won her bet within two weeks. Eventually in 1973 she edited the resulting ground-breaking anthology Two Centuries of African English, which became a core text throughout Africa.

Lalage went on to set up a network of adult education institutions in Uganda, Zambia, Kenya and Tanzania. In particular, she worked in Nigeria, where she taught at the University of Ibadan and the Ahmadu Bello University, before taking on the role of Dean of the Faculty of Education at the University of Lagos. As founding Secretary of the African Adult Education Association and an active participant in the formation of the Nigerian National Council for Adult Education, she set up the first systematic training for adult educators in Africa. She was especially concerned about women’s literacy which she saw brought about ‘a huge change in their selfworth and confidence.’ Whilst in Nigeria she took into her home five-year-old twin girls, victims of the war, and she became their permanent foster mother. She was awarded an OBE in 1977.

Lalage returned to the UK in 1981 as Head of the Adult and Continuing Education Department at the University of Glasgow, and was recognised with honorary professorships at the University of Warwick and the University of London Institute of Education.

In 1992, she retired to Shrewsbury, where she was a member of the Rotary Club and numerous international societies and

boards. She enjoyed collecting ancient gravestone epitaphs, cooking, reading and, despite ‘a slightly groggy knee’, striding over the hills. She supported the Shrewsbury museums and organised a ‘Talking Newspaper’ for the blind.

During Covid lockdown, still living alone, she mastered Zoom and in 2020 she recorded a message for Somervillians. (link please, Jack). She always retained a great affection for Somerville (regularly making the journey to attend College events into her 90s) and a respect for its values. As she recorded: ‘My small cohort of students back in 1945 included people from Denmark, France, Poland, Guyana and New Zealand, as well as the daughter of a Nottinghamshire coal miner and a student from a background such that, to my amazement, she’d never learned to make her own bed. In addition, my Maths friend had worked during the war as a computer (in those days, a computer was a human being), and my literature friend later became a distinguished novelist. In what other environment can one go forward in life with such a range of friendships and of varied knowledge?’

Lalage died, aged 94, after a brief stay in hospital, following a fall.

Cecily Littleton (Darwin, 1945)

Cecily Darwin was born on 15 November 1926 in Edinburgh, where her father Charles Galton Darwin was Tait Professor of Natural Philosophy at the university. Her paternal greatgrandfather was the naturalist Charles Robert Darwin, and her grandfather was George Howard Darwin, Plumian Professor of Astronomy at Cambridge University. Through her mother Katharine Darwin (née Pember), Cecily was granddaughter of Francis William Pember, a vice-chancellor of Oxford University in the second half of the 1920s. And it was to Oxford, specifically Somerville, that she turned after completing her secondary education during the war in schools in Hertfordshire and Cambridge. She and her next brother remained in England while her parents and three younger brothers were in the United States on a British scientific mission in 1941-42.

Cecily studied Chemistry at Somerville, specialising in X-ray crystallography under the Nobel Prize-winning Dorothy Hodgkin. One of Cecily’s contemporaries in the Chemistry programme was Margaret Roberts, later Thatcher. During the 1980s we pressed Cecily for what she could tell us of Lady Thatcher’s student days, but she always claimed that they had not known each other well. She spoke more often and fondly of her great friends from Somerville, Patricia Mears (later Beesley) and Josie Hamilton (later Millar), with whom she maintained life-long friendships. Cecily also retained a great affection for Dorothy Hodgkin, mixed with a fair bit of awe. She once told us of a nightmare she had had which involved the terror of being unprepared before a meeting with her redoubtable tutor. However, Hodgkin acted as co-author to Cecily’s 1950 Letter in the journal Nature which described her thesis work. In 1949, having graduated from Somerville, Cecily was offered a research fellowship under Arthur Lindo Patterson at the Institute of Cancer Research at Fox Chase, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At a New Year’s party at the end of her first year in the US she met John Littleton, a Philadelphia native and veteran of the Pacific War who had studied Jurisprudence at New College while Cecily had been at Somerville. Their paths had not crossed while they had been at Oxford together, but fortunately did in Philadelphia. They married in Cambridge in 1951 and she spent the rest of her life with John, a lawyer in a Philadelphia firm, in Wynnewood and, later, Haverford, Pennsylvania. She had her first child in 1952 and resigned from her research post in 1953 (after having published another article on her crystallographic research) to raise her growing family – a further three children between 1954 and 1963. She kept her scientific interests alive and worked as a volunteer with Louis C. Green of the Astronomy Department at Haverford College on the spectra of distant stars. She did much of this work at home, with graph paper spread across the dining-room table as she did calculations with her trusty slide rule. Gardening was her great passion. She took botany courses at the Barnes Foundation so she could work as unofficial landscape gardener at her sons’ school, The Episcopal Academy in Merion. She continued that interest when she and John moved to The Quadrangle, a retirement community in Haverford, in 2002. John died there in June 2009 and she died, peacefully in her sleep, on 14 April 2022. She is survived by her four children, seven grandchildren, and one great-grandchild. She always emphasised her English roots, and two of her descendants have in turn settled in the UK.

CECILY LITTLETON AT WORK AS A CRYSTALLOGRAPHER, 1949

Charles Littleton, son

Elizabeth Fortescue Hitchins (Baldwin, 1946)

Elizabeth, the only daughter of Marjorie and George Baldwin, was brought up in Northamptonshire initially, then the Fens. She went up to Somerville to read History, after a year out at the Ecole Hôtelière in Lausanne, where she learnt some of the mysteries of French cooking.

At Oxford she made life-long friends, Edna Thomas and Christian Carritt in particular, and clearly enjoyed being part of a lively crowd. She met her future husband, Tom Fortescue Hitchins of Trinity College. They married in 1951 at St Paul’s Knightsbridge. At the time she was working in an advertising agency in London, but after marriage she followed Tom in his military career.

Once Tom started to work at the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall she began her own career in the Civil Service, as a Principal in the Department of Transport, and later Assistant Secretary in the Department of the Environment. Here her portfolio included preparatory work for the Channel Tunnel. Her time at Marsham Street was particularly happy as it enabled her to drive home for lunch at First Street, after which she would frequently take her first pug Augustus back to the office in the afternoon, combining her two great interests: administration and dogs.

After she retired from the Civil Service in 1982, Elizabeth focused on her great capacity for friendship: old friends from Oxford and the Army, new friends in London and later many friends in Somerset. She was naturally sociable. She began to paint, initially attending classes in London, with frequent painting trips abroad, followed by classes in Somerset once she had moved there. She was not much interested in the technical but she was clever at painting en plein air, dashing things off before returning to base for a drink or snack or another paper plate on which to mix her colours. She loved poetry and had a formidable capacity to recall some very long poems she had learnt at school.

Elizabeth became a Roman Catholic whilst living in Tripoli in 1962. She took this very seriously, enjoying many an intense discussion. From the mid-1960s she lived close to the Brompton Oratory, and used to slip in and out of mass several times a week. She was also keenly aware of her Christian duty to help others less fortunate than she was. I remember often returning to First Street to find another hopeless couple ensconced on our sofa while my parents handed out tea and advice and usually cash too.

The Somerset years, at least twenty spent with my father, were happy ones. There were the dogs and the rescue chickens in a pen in the garden: saved from battery farms, only to be sacrificed to the jaws of local foxes, to great lamentation. And there was a life with a comforting structure, punctuated by frequent drinks or meals, in the garden whenever possible. There were shopping trips which my parents both enjoyed. After my father died she missed all this very much, particularly as she could no longer drive. Over her last year she battled on bravely, never really believing she would not be back on the road soon, often talking about moving to London. It was brave and it was feisty, so typical of my mother, a force of nature who left this earth on the tail winds of a storm. We will all miss her terribly.

Francesca Simon, daughter

Susan Elspeth Chitty (Hopkinson, 1947)

Susan was born in 1929 to novelist Antonia White and geologist Rudolph Glossop. But her relationship with her mother was not a happy one. Later she summarised it succinctly in a memoir of Antonia: ‘Antonia was not a good mother to me. She conceived me out of wedlock, put me into a home for the first year and a half of my life, and handed me over to nannies and boarding schools for much of the remainder of my childhood.’

The young Susan equally disliked London, but childhood holidays at her grandparents’ home in Binesfield, Sussex, inspired a love of horses and countryside that was to last the rest of her life. She wrote: ‘It was summer, and the dew was sparkling. I ran down the garden … along by the yew hedge. I ran with such speed and lightness that I seemed weightless. There was a taste of freshly baked bread in my mouth.’

Having attended the Godolphin School, Salisbury, where she decided that ‘rules were not for me’, she won an Exhibition to study Modern History at Somerville College. After a nervous breakdown, she left Oxford without a degree, but won the Vogue Talent Contest in 1952, and started a career in journalism, later becoming a regular contributor to radio programmes such as Any Questions and Woman’s Hour.

Eldest son Andrew was born (1952), prompting his parents’ move to Sussex. Rejecting the polluted London air and expunging memories of her own city childhood, Susan wanted a country upbringing for her children. The rural village of West Hoathly became base-camp for her and husband Thomas Chitty, an aspiring writer she had met at Oxford.

Her first novel, The Diary of a Fashion Model (1958), which drew humorously on her experiences at Vogue, came out just as the couple moved to Kenya for two years, Thomas then working in PR for Shell. Their adventures included driving 3,000 miles with the children in a Land Rover from Nairobi to Cape Town. Back in Sussex, Susan wrote two more novels: White Huntress (1963), about daring debutantes in Africa, and My Life and Horses (1966), inspired by her love of horses.

The family then lived in America between 1965 and 1971 where Thomas, now a successful novelist, taught literature. Somewhat frustrated by her role as a housewife, Susan decided they should have more children; Miranda and Jessica arrived in 1967 and 1971.

SUSAN CHITTY

But the greatest adventure was still to come. In 1975 they set off with Jessica (then aged 3), Miranda (7), Andrew (21), two donkeys and a dog to walk 1,700 miles across Europe starting from Santiago de Compostela. The story was told in the co-authored The Great Donkey Walk. Asked later why she had agreed to go, Susan said because Thomas’s alternative suggestion – sailing a small boat around the world – seemed infinitely more dangerous.

Continuing her literary career both before and after, Susan published biographies of Anna Sewell, Charles Kingsley, Gwen John, Edward Lear and Henry Newbolt, as well as the memoir of Antonia White. Her biographies were mostly about seemingly prim Victorians, but she was always able to find some undivulged secrets about their private lives, and was never one to shy away from a good story.

A natural entertainer, she loved dressing up, charades and singing. She learned and imparted dozens of songs and revelled in her rendition of The Cruel Mother, one who murdered her two unbaptised children, using the original Sussex accent.

Another co-authored book, On Next to Nothing, taught frugality, an area on which the couple could never agree. But this did not prevent them from entertaining. Thomas cooked and Susan was the star of the show. She was flamboyant, elegant, fearless, forthright, witty, inventive, and irreverent but always great company.

Towards the end, she lived at Miranda’s home cared for by her two younger children. She died there after a short illness in July 2021.

GILLIAN MACKIE

Gillian Vallance Mackie (Faulkner, 1949)

Gillian was born in Iffley in 1931, but in 1941 she moved with her mother and sister to Ship Street in the heart of Oxford. Both girls went to Greycotes School and then to Westonbirt on scholarships, as Gillian described in a memoir about her school years. In 1949 she went up to Somerville as a Powell Scholar, obtained the BA (Hons) in Zoology in 1953, and MA in 1958. She then embarked on a doctoral programme under Prof. Sinisa Stankovic in Belgrade. Her project involved the speciation of turbellarians in streams feeding into Lake Ohrid, but the thesis never came to fruition as she married her boyfriend, George Mackie, in 1955 and this was followed by the birth in Oxford of the first two of their five children. Her time in Yugoslavia was far from wasted as it left her with a fascination for the art and architecture of the great mediaeval sites of the Serbian Orthodox Church, such as the tenthcentury monastery church of Sveti Naum in Ohrid. George was appointed to a lectureship at the University of Alberta in 1956, and the couple made Edmonton their home for twelve years and had three more children. Rapid advancement and friendly people made up for the awful winters, but in 1968 George obtained a position at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, a beautiful part of the world with a climate much like that of England. Gillian was gifted in the arts and crafts, and found time to weave rugs from wool she dyed with her own home-made dyes and to make quilts and stoneware and porcelain pottery, but it was not until her children were beginning to fledge their wings that she could start taking university courses again, initially on a part-time basis. With a

President’s Scholarship she started learning Serbo-Croatian and taking courses in art history. This led to the BA degree in 1981 and the MA in 1984. Finally, in 1991, almost forty years after her interest in mediaeval art was first aroused in Macedonia, she obtained her PhD with a brilliant doctoral dissertation on mediaeval chapels that won her the Governor General of Canada’s Gold Medal. Gillian’s focus was on late antique and early mediaeval art and her base for much of her doctoral and postdoctoral work was the British School at Rome, where rooms were available for visiting scholars and the library was richly stocked with material relevant to her work. A stream of publications over the next ten years culminated in publication of her book Early Christian Chapels in the West (University of Toronto Press, 2003). Her forte was the interpretation of mosaic images. An outstanding iconographic achievement was her identification of the ‘running saint’ in the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna as St Vincent of Saragossa, not St Lawrence as previously supposed. Key elements associated with St Vincent’s martyrdom can be clearly recognised in the panel mosaic. Gillian taught courses in the History in Art Department at the University of Victoria for several years and continued to travel and do research well into her seventies. Her last major paper came out in 2010. Five years later she fell ill with Alzheimer’s. She is survived by her sister Patricia, husband George, and daughters Christina and Ra.

George Mackie

Bridget Ann Davies (1950)

Bridget was born on 6 December 1930, the daughter of Philip Taliesen Davies. Her father came up to Oxford in 1914 and one of his sisters to Somerville in 1913. Her stepfather, Herbert Freundlich, was a distinguished physicist who had been called to an atomic bomb project in Chalk River, Canada, in the Second World War, living there with his wife and stepdaughters. On returning to England, the family lived in Cambridge and Bridget attended the Perse School, coming up to Somerville in 1950 to read Physiology. Her sister Gillian followed her to Somerville in 1953. Bridget described Jean Banister as an outstanding tutor and friend and the course as challenging and exciting. But she also found time for other activities, mainly singing, politics and conversation. She made lifelong friendships, most notably with Liz McLean (Hunter, 1950).

After qualifying Bridget did jobs in obstetrics, paediatrics and general medicine before moving into psychiatry, working in and around London until 1970 when she became a consultant at St John’s Hospital, Stone, near Aylesbury, and moved to Long Crendon. Bridget described her work as ‘interesting, often humbling and exhausting. I don’t think I would have lasted until 1992 when I retired without the refreshment of music, singing in various choirs and playing my late-start cello (with more enthusiasm than skill), mainly string quartets and trio sonatas, with tolerant friends (including Liz McLean). A large untidy garden, holidays walking, particularly in Cornwall and the Lake District, and birdwatching helped too.’ She sang second soprano in the Thame Chamber Choir for many years, favouring Bach and William Byrd over more modern composers. Not really a churchgoer, she explained to the vicar that ‘Bach was so close to God as to be enough’.

Bridget is described by her friend Andre McLean as extraordinarily kind and generous with her time. ‘The long telephone discussions about politics, developments in medicine and what’s growing in the garden! She strongly believed in community action. Helping those who needed help. Making the system fairer. Her enjoyment in meeting people, her clear thinking, informed her work as a psychiatrist.’

After retirement Bridget became more involved in village activities and increased her time for music. She also travelled more, including to Israel, Chile, Peru, India, and Nepal. In the last ten years until lockdown she worked as a volunteer in the Long Crendon village library; she enjoyed that very much though sometimes challenged by the computer. According to Andre, taking out a book might have risked taking a little longer than usual as she grappled with the antiquated Buckinghamshire County Council computer system. ‘Even longer if you engaged in a conversation. She was extremely well-read and had backpacked extensively all over the world. A sharp mind, you had to applaud her prodigious knowledge and storytelling. Not a conversation for the faint-hearted.’ She conquered her technical phobia and purchased a laptop in 2010, becoming proficient at email and, during the pandemic, at Zoom.

She belonged to the Labour Party for ten years in London and after retirement re-joined as an active member, enjoying canvassing in the early days and being chair of the local Brill

BRIDGET DAVIES

branch for many years. The Secretary of the branch at the time, Professor Sir Roderick Floud, said that Bridget ‘was quietly inspiring’ and that under her leadership the branch had built up its membership and its ability to run more candidates in local elections.

Bridget never married and had no children; this was a sadness to her but she said it might have made it easier for her to concentrate on work. Her sister Jill also had no children. Jill died in 2006 but they had enjoyed many holidays together and lived only five miles apart during the last ten years of Jill’s life.

Lucia Turner (Glanville, 1951)

Lucia was the younger daughter of Stephen and Ethel Glanville, born in Highgate on 27 November 1932. Her sister, Catherine, remained her closest friend till she died in 2012. Lucia was sent to Channing School at the outbreak of war and in 1941 she was evacuated with her mother and Catherine to Canada (the next two liners carrying children to North America were both sunk). Those two years in Toronto, with riding in ‘The Ravine’ and summer camp at Lake Oconto, became precious memories.

Back at Channing, Lucia won a scholarship to Somerville. Gaining a First, specialising in Middle English, she stayed up to take a BLitt with a treatise on Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. She was launched on a promising academic career. Her first employment was to be a lecturer in English literature at King’s College London. First, though, she spent a few months in Cambridge housekeeping for Stephen, who was now Provost of King’s College. Tragically, that ended abruptly in April 1956, when Stephen died suddenly.

Two years at King’s College London ended with Lucia’s appointment as a tutor in LMH, Oxford, and university lecturer in Middle English. That, however, was to be the last step in her university career. Lucia had an acute mind, an exceptionally retentive memory and a gift for clarity; but she also had a large heart, loved people, and had a strong commitment of faith as a Christian. Endowed with a superb singing voice, she had re-joined the Bach Choir, and it was there she got to know a young man from the basses whom she recognised from his tenure nine years earlier as vice-president of the Christian Union. Christopher and Lucia were engaged two months later and married the following summer.

Their first home was in Godalming, Christopher being newly appointed head of Classics at Charterhouse. In the seven years there, their three children were born. Lucia started work on a new textbook of Border ballads, but, regretfully, abandoned it in favour of being an almost full-time mother. In 1968, Christopher became head of Dean Close School Cheltenham. The children were starting school so Lucia found time to teach and to sing. In 1979, the family moved to the headmaster’s house at Stowe School. Lucia supervised girl-boarders in the house, as she had done at Dean Close. Her kind but firm care of them was remembered with gratitude. Her teaching commitment grew. Lucia was the ideal headmaster’s wife, providing rock-like support to her husband while being a most accessible, warmhearted friend to pupils, staff and their families. Her calm, wise advice and sympathetic understanding of adolescence, leavened by her irrepressible capacity for mirth, were invaluable as the schools moved into full co-education.

In June 1989, their elder daughter, Rosalie (married in 1987), was killed in a road accident. The next morning, with unbelievable courage, Lucia spoke in the school chapel and was heard in shocked, admiring silence.

Back in 1966 the family had bought their first house, a seaside cottage in Gower. It proved to be the ideal family base for holidays, usually shared with family and friends. In 1984, that was replaced by Rosemullion in Great Rollright. It was to there that Christopher and Lucia ‘retired’. But between 1990 and 1999 they added a second, smaller house in outer Birmingham where together they spent the middle of each week as informal remedial teachers in a primary school. Meanwhile Christopher was embarking on ordained ministry in Oxfordshire at the weekends. This ministry was always a team effort as had been their work at Dean Close and Stowe. Lucia served as churchwarden for many years and was a heroic pastoral visitor. Then, as her responsibilities diminished, she found time to develop her understated skills in art and crafts. In 2012, after a year of declining health, Catherine died. Lucia’s grief was deep and silent; some of her sparkle had gone. By 2020 the ‘children’ were married with young of their own to whom Lucia was a much-loved Granny. In 2021, Lucia and Christopher celebrated their diamond wedding with a village party, gloriously released from lockdowns.

LUCIA TURNER

Christopher Turner

Ann Hall, an only child, was born in Derby to (Herbert) Leslie and Dora Hall on 1 May 1936. The family moved to Newcastle-under-Lyme when Ann was 15. Ann came up to Somerville in 1954 to read Geography. Her family had no academic inclinations, but Ann had many fond memories of her time at Somerville.

It was Ann’s dream to become a hospital almoner (later redesignated ‘social worker’). She trained at Bedford College, London, and spent a few years working for the Invalid Children’s Aid Association. Sadly, health issues prevented her from pursuing this career further but she remained full of compassion for those in need and, whenever possible, sought to help them.

Ann was also a lifelong, devout Christian and worked for the Bible Society, as long as her health permitted, in London and subsequently in Swindon, when the Society relocated there in the mid-1980s. The church remained a central feature in Ann’s life and she was an active member at her local ecumenical church in Swindon for many years, although faithful to her roots in the Church of England.

A remarkable woman for her modesty and her endurance of disabling health problems, she will be fondly remembered.

Avril Greig, cousin

Anne Elizabeth Fuller (Havens, 1953)

Anne was born in 1932 in Pomona, and lived her first four years in nearby Claremont, where her father, Paul Havens, taught literature at Scripps College. In 1936, Paul moved his family to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he had accepted a post as president of Wilson College.

After graduating magna cum laude with a BA in English Literature from Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts in 1953, Anne was awarded a Fulbright grant to read English at Somerville. In 1958 she completed a PhD in English at Yale.

She taught for two years at her alma mater, Mount Holyoke, then accepted a comparable position at Pomona College, in Claremont, returning thus to her birthplace. She met PhD chemist Martin Fuller at Pomona, and the two were married at St Ambrose Episcopal Church in Claremont on June 17, 1961. Children Kate and Peter followed soon after in 1962 and 1963.

She then taught at the University of Florida, the University of Denver, Prescott College in Arizona, the Colorado Rocky Mountain Prep School, and again at the University of Denver.

In 1973, she was offered and accepted the Dean of Faculty position at Scripps College. She later worked at Claremont Graduate University as assistant to the president, then moved to Sherman, Texas, where she took on the Dean of Faculty role at Austin College. She was a gifted teacher who read voraciously and loved to learn. She instilled in her students a deep respect for English and other languages and cultures and their respective histories, as well as a love of Chaucer and other medieval literature, and Old English, including Beowulf.

In 1996, the couple retired to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Martin died in 2007, and in 2014 she moved to La Vida Llena Life Plan Community, where she led an active life. She swam every morning well into her eighties, and continued to involve herself in book clubs and to share her love of literature and learning with her friends and neighbours. She will be missed by many.

Peter Fuller

Jane Cecily Gibbs (Eyre, 1954)

Jane came up to Somerville in 1954 to read History. Jane loved her time at Oxford, and kept in lifelong touch with the many close friends she made there.

Jane had an adventurous upbringing. She was born on 14 October 1935 in Tanga, then Tanganyika, the eldest of four children of Jack and Maureen Eyre. Jack worked for the Colonial Service advising on agriculture. Maureen, from Derbyshire, had had a strict sheltered Catholic upbringing.

Towards the end of 1944 whilst Europe and Africa were still ablaze with the horrors of the Second World War, Jack and the family were posted to Palestine. As the Palestinian situation became worse Maureen and the children were evacuated to Britain on a troop ship through the Mediterranean.

Jane had little formal schooling before the age of eleven. But she had plenty of access to books and developed a lifelong passion for literature. When the family was reposted to what was then Rhodesia, Jane was left behind in England to attend a convent boarding school in Hastings.

The convent school was not a happy place for Jane, and she would entertain with stories of her escapades and determination to experience life outside the rigid convent rules. Even Christmas, Easter and summer holidays were difficult, her parents advertising and arranging for unknown chaperones to care for Jane. She did not see her family for close to three years. Through all of this she drew solace from books and poetry.

Jane was clever, excelled at school, and fulfilled her dream of winning an Oxford place to read history. At Oxford Jane was known as lively and, in her tutor’s words, a ‘social butterfly’. The nameplate on her door, ‘Jane Eyre’, drew attention though more was not needed. Jane’s room mantelpiece was covered in invitations, and she recounted that it was not uncommon to go on two dates on one night. And Jane said that the girls always knew what they were doing on a Friday night, as the men students would always ask them out for fish suppers. Daisy and Kitty Eyre, two of Jane’s three granddaughters, commented that ‘this always sounded very glamourous!’ A friend wrote: ‘Please tell Jack that his daughter is the boon and bright light

JANE GIBBS

of Somerville – no really…. – a girl who lightens the days and makes living here possible. Words cannot describe.’

The lifelong friendships formed included Anne, Lyndon, Elizabeth, Halina, Giustina and many others. She, and their families, would meet regularly over more than fifty years.

Jane married Patrick not long after leaving Oxford, twenty years older, film critic of the Daily Telegraph, and a decorated wartime torpedo Wing Commander. Patrick was not a university graduate, but had the same passion for reading, for theatre, for opera and for European holidays and culture. Jane had embarked on a career in the Civil Service and was studying law but abandoned these to support Patrick, including joining him at film festivals from Hyderabad to Chicago, and to bring up their family. Jane and Patrick had two children, Christopher and Penelope, Penelope herself going on to read History at Somerville.

The hallmark of Jane was that she got on with everybody, from a brief shop assistant or restaurant waiter encounter, to the staff at her care home, to her English-as-a-foreign-language Berlitz students, to her lifelong friends and family. She always took an interest in others, listened really well, and had an excellent memory. She could fully empathise with someone else’s story as well as tell her own vividly and engagingly.

Relationships are what matter; some of Jane’s very best were from Oxford. Jane will be much missed by friends and family.

Penelope and Christopher Gibbs

LYNDEN MOORE

Lynden Margaret Moore (1954)

Lynden Moore, who died on 4 January 2022, graduated from Somerville with a degree in PPE, and went on to become an applied economist and author of several books on subjects including international trade, the British cotton industry, and the British economy during membership of the European Union. She was a loving mother to two children, a keen gardener, a wonderful if short-tempered cook, and throughout her life retained a passion for world politics, and above all events in South Asia, the region where she spent her first childhood years.

Moore was born to missionary parents in the northern Indian hill station of Shimla in May 1935. She spent the first ten years of her life in India, including a long stay in a hospital after contracting rheumatic fever, due she believed to wearing inappropriately light clothing for the town in the Himalayan foothills where she went to school. The experience of spending six months in a hospital flat on her back, she used to say, meant she was always able to rely on her imagination to entertain and distract her. The sights and smells of northern India left an indelible impression upon her, as did the experience of seeing poor Indian house servants working for her parents. For the rest of her life, she refused to eat sandwiches from which the crust has been cut after witnessing how leftover bread was handed to the staff of her home to supplement their diet.

Upon returning to Britain with her family in 1945, Moore found herself both excelling as a student at school in Slough and also handling multiple responsibilities at home, including caring for a brother with Down’s Syndrome and a sister with brain damage. Her skills as cook, child carer and general substitute mother – and her fierce love of her sister Daphne, who died aged 24

– were legendary in the family by the time she was in her teens. Gaining a place to read Chemistry in Oxford provided an exit from the onus of family life, and also a chance to express her disagreement with her parents’ religious beliefs. Within the first year at Somerville she realised that her deepest longing was in fact to study real-world affairs, and as a result she managed to get permission to switch to PPE.

Her career as a professional economist began at the Agricultural Economics Research Institute in Oxford, under the stewardship of Colin Clark, and soon after she married the Latin scholar Dr John Briscoe and gave birth to two children, Celia and Ivan (her divorce came a few years later). Moving to Manchester in 1970, she took up the post of lecturer in the Department of Economics, and over the course of 25 years trained generations of economists, including postgraduate students from numerous countries. Her regular production of books, articles and lecture courses could not, however, hide her dissatisfaction with the department’s refusal to give her proper credit and promotion, or her desire to escape and rediscover the world. This she finally did after retirement, when she returned regularly to India, and, in 2006, against the advice of almost all her family, embarked on a trip to look for work as an economic adviser in Afghanistan. Until the age of 80 she continued to devote hours to studying Farsi and Spanish, and regularly attended seminars in Oxford.

Lynden’s last years were spent in the Freeland Care Home, where she received regular visits from her children and grandchildren until the pandemic struck, and could enjoy the Oxfordshire countryside that she so loved.

Ivan Briscoe, son

Elizabeth Roberta Cameron (‘Elspeth’) Barker (Langlands, 1958)

My mother died in April 2022. Near her house in Norfolk, beech trees spread their canopy, a glimmer above the bluebell haze in the woods where she walked. I picture her there across the years of my life.

I was born when she was newly in love with my father, George Barker. They moved to a tumbling farmhouse in Norfolk where she was a glamorous figure, in big hats and fur coats, carrying a picnic to the bluebell woods. A decade on, she rode horseback, children behind on ponies. Another decade, dogs, teenagers with her small grandchildren on the shoulders. Elspeth teaching wild flower names, Latin and vernacular, sharing her love of the countryside. Another decade, bigger grandchildren, Elspeth’s beloved Labradors, and, lo! A unicorn, created by Elspeth for her granddaughter. Elspeth lived with the magical relationship between the imagination and reality central to her existence. Her childhood was inspiration for O Caledonia. Published when she was 51, the novel depicted a painfully sensitive heroine living, and yearning for drama, in a Gothic Scottish castle.

Elspeth was born in 1940, the eldest of five children. Her family lived between Drumtochty Castle in Aberdeenshire and Ely in Fife, and Elspeth’s upbringing was traditional. She loved the Highlands, and in O Caledonia reveals a metaphysical relationship with nature. This quality, and her passion for reading, were constants in a life that became filled with much more and, as The Times obituary said, ‘was never, ever dull.’

After St Leonard’s School, St Andrews, Elspeth read Modern Languages at Somerville. She was 17, and adopted a style, pale skin, black eyeliner, wild black hair and dramatic clothing, that would remain with her always. She was beautiful, erudite, funny, yet hopelessly impractical, had no clue about money and little interest in domestic issues. She was shy but had hundreds of friends, was always extremely short of money, but uninterested in comfort, choosing a wooden dining chair over the sofa for watching television.

From Oxford, where she fell asleep in her Finals, Elspeth moved to London and worked in Foyles bookshop and as a waitress in a Lyons Corner House coffee shop. Her friend Kate Leavis says she was ‘extraordinarily attractive to men’. Her own stories included numerous fiancés and a man who said he had married her by proxy and would take her back to his home in Nigeria.

Elspeth was 24 when I was born. She had met my father, a famous poet and womaniser, through his former partner Elizabeth Smart. My parents’ life in Norfolk was inclusive of friends and family. The parties at our house were legendary for the explosive behaviours, the poetry and the range of people present. As children in the midst of this sprawling Bohemian world, we lived enthralling lives, largely oblivious to the literary life of our father, and the pioneering spirit of our mother, who drove illegally to her job teaching Latin at a girls’ school with a blonde wig on to disguise herself from the police (she passed her driving test on the 24th attempt).

My father lived to see O Caledonia published and was proud of her. My mother couldn’t accept the finality of his death. Her

ELSPETH BARKER

success took her to Australia and New York. When she came back, she acquired a horse and another Labrador and wrote and gardened, telling great stories to friends who came to laugh and drink at the kitchen table. She learned Russian, and Ancient Greek at summer schools in London, and taught creative writing at Norwich Art School, and on Arvon Foundation courses. She reviewed brilliantly for various newspapers and drank her friends under the table.

O Caledonia, ‘one of the best least-known novels of the 20th century’, according to Ali Smith, was reissued in 2021. By then, Elspeth lived quietly in a residential care home. As this book, rich with incidents of her childhood, became widely read, in her mind she also inhabited more often the sandy beaches of Ely in Fife, and her childhood highland haunts.

In her last days, she talked of the canopies of beech trees and the picnics in the woods she loved. She is buried in the village churchyard close to the bluebell woods. She is hugely missed, and unforgettable.

Raffaella Barker, daughter

Marian Joyce Nelson (1960)

Marian was born in the Isle of Man in 1940. She and I met when we started elementary school in Douglas at the age of five. We became good friends and remained close companions till our paths diverged in 1951, when I went off to boarding school in England.

Marian continued through the Manx education system, eventually attending Douglas High School, where, in the sixth form, she specialised in Latin and Greek. She was joined there by fellow classicist Marilyn Wright, and the two of them came under the sway of a rather singular teacher called Mr Wille, who had read Greats at Oxford. Eccentric, cricket-mad Mr Wille was from Ceylon, of Dutch descent. In term time he lived in a hotel on Douglas promenade; in the holidays he joined his wife in London. For all his idiosyncrasies he was a good teacher and, recalls a fellow pupil of Marian and Marilyn, ‘never sarcastic’. They often spoke about him.

In 1960 Marian and Marilyn both came up to Somerville to read Classics. I was already there, having come up in 1959 from my boarding school. It was remarkable that, within the small set of Classicists at Somerville, three of us came from the Isle of Man; even more remarkable that two came from the same Manx high school. The 1960 Classics year were a closeknit, friendly group and constituted a cheerful, hospitable household at No 17b Woodstock Road, home to most of them during their final two years.

Marian began her working life at the Home Office in Whitehall, but her interests took her north to Granada Television in Manchester, with whom she had a 22-year career. She was increasingly involved in programme creation and production, working initially on programmes such as World in Action and What the Papers Say, and moving on to a seven-year stint in the schools department. In 1980 she moved to Granada’s newly opened Liverpool office and produced news programmes and chat shows, one of her favourite creations being a food programme called On the Market.

In 1972 Marian had met Rob Rohrer and the two became partners. Rob already had a son, Daniel, from his previous marriage, and Marian and he had three more children, two sons with the Manx names Finlo and Kerron, and a daughter, Rosa. In the late 1980s Marian took voluntary redundancy from Granada and she and Rob went into independent production. The reading series for four-to-six-year-olds called Story World was a brainchild of Marian’s. Rob directed films such as The Man from the Pru and made documentaries for Channel 4.

As the millennium and retirement approached, instead of relaxing Marian set herself academic challenges. She took an A Level in Italian and joined Liverpool University to work on an MSc that called for a complete change of direction into the realms of biology and physiology: her subject was ‘The Role of the Menopause’. Success with that led her on still further to take a PhD in evolutionary psychology.

In 2014 Rob was diagnosed with cancer of the oesophagus. He and Marian married before his death a few months later. In 2016 Marian sold their Liverpool home and bought a house in a new estate in the south of the Isle of Man, where I would visit her when I was over. In August 2021 she had become much frailer and was being looked after by a succession of carers. Her mind was sharp, but she was struggling to remember words. She died on 2 January this year. She is survived by her brother Roger, her four children, and ten grandchildren.

Marian had a strong personality and made confident decisions that led to substantial achievements. She took a pride in Manx culture, was a member of the Manx Historical Society, and learnt Manx at an early stage. She was also very good fun; even as a child she had a dry wit. She had an expressive voice, quite deep, and sounded distinctively Manx.

MARIAN NELSON

Marilyn Dorothy Woodside (Wright, 1960)

Marilyn, who died last year, was born in 1941 in the Isle of Man. She showed early promise in two of her later great interests: at primary school she played piano solos in school concerts, and her poem on Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain was published in the school magazine. At Douglas High School for Girls, she and her friend Marian Nelson were taught by an inspirational classicist, Mr Wille, and as a result both applied to Somerville to read Greats and were accepted, Marilyn being awarded the Bull scholarship. Theirs was a bumper year – there were six of them; for the last two years, four of them lived cheerfully in a ‘Classics enclave’ in the somewhat quirky 17b Woodstock Road over a newsagent’s shop, with Doreen Innes from Aberdeen University, who was actually the same age, as their ‘graduate in charge’. In the ‘great freeze’ of 1963, all their pipes froze, so Dame Janet Vaughan came to the rescue, letting them use the bathroom in the Principal’s house. In 1962 after Mods, Marilyn received a Lorimer prize, and after Greats the T. W. Greene Scholarship helped her to do the two-year Diploma in Classical Archaeology (achieved in 1966 with Distinction). I was a year ahead of her, and we spent happy hours poring over books of Greek art together and arguing for our favourite fields. Marilyn especially loved prehistoric, Minoan and Mycenaean art, and Greek architecture. During and after the Diploma, Marilyn travelled for study in Greece, staying several times at the British School of Archaeology in Athens. In 1965 she helped the veteran archaeologist Sylvia Benton, presiding genius of Room 2 in the old Ashmolean Library, in Ithaca, and in 1967 she was at Prof. Peter Warren’s Minoan dig at Myrtos in Crete. She also lived for some time in Euboea and Athens with the family of the scholar Philip Sherrard, helping with the care and education of his two young daughters. She is remembered affectionately, and was much appreciated for her lively companionship. Marilyn then returned to the Isle of Man, which she loved deeply, and where she lived for the rest of her life. There she had a brief marriage to John Woodside. She was very knowledgeable about Manx archaeology and did notable work for Marshall Cubbon, then Director of the Manx Museum, preparing for publication the notes and finds from the excavations of the distinguished German archaeologist Gerhard Bersu (who after moving to England in 1937 was interned as an ‘enemy alien’ in the Isle of Man during the Second World War, but was allowed to dig – under armed guard, using only trowels!). His digs were at several sites, among the most important being the Celtic roundhouses at Ballacagen near Castletown. Marilyn herself published an article on Bersu’s finds at Peel Castle in Proceedings of the Isle of Man Historical and Antiquarian Society. Marilyn was a passionate advocate of the revival of the Manx language, which she and Marian Nelson both studied. She told me how much she enjoyed chatting in Manx to fellow students. She was also a talented artist, producing exquisite sketches and cards over which she took infinite care. Her love of the piano became increasingly important to her. She was a fine pianist, and made several visits to play the historic instruments at Finchcocks in Kent, and to attend music courses at Dartington. By scrimping and saving, she acquired two square pianos, which she cherished and considered superior to modern grand pianos. Marilyn’s later life was not always easy, but she never lost her passion and enthusiasm for the subjects she loved. She visited us several times and was always an interesting, fun and stimulating companion who inspired both admiration for her talents and lasting affection. I would like to thank Helen Hughes Brock and Anne Seaton for their generous help with details of Marilyn’s life in Greece and in the Isle of Man respectively.

Beryl Bowen (Lodge, 1959)

Harriet was born in Nottingham, and her family lived first in Harrogate, and then in Newcastle, where she and her younger sister Katherine grew up. She attended Central Newcastle High School for girls, and later boarded at Bedales School in Sussex, where she was an apt scholar in many subjects, particularly literature and languages. She was also a very talented artist, and she spent a lot of her free time at school sketching, painting, and working on creative projects such as sewing and weaving.

In 1961, Harriet came up to Oxford to do a degree in Medieval English and French at Somerville College. At Oxford, she made friendships that lasted her whole lifetime. She was a member of the heritage folk society, singing and playing her guitar with them at various venues around Oxford. She often used to surprise people by slipping from her usual cut-glass accent into broad Geordie at the drop of a hat; one of her party pieces was singing Geordie folk songs such as ‘Blaydon Races’ and ‘The Lambton Worm’, accompanying herself on the guitar.

A lot of her Oxford memories seemed to consist of climbing back into college after curfew, and her social life was busy. She wrote of that time: ‘Somerville provided wonderful friends, and Oxford a magical environment of bookishness and fun, with its beautiful parks, streets and buildings, its chaotic student social life, and quirky encounters.’

After graduating, Harriet completed a teaching qualification and taught English and French at secondary level for a few years, before deciding that her very detail-oriented and process-driven approach to life would make her an excellent administrator. Her work took her to the NHS, the Law, women’s magazines, and scientific research.

Harriet married schoolmaster Morris Fishman in 1970, and they lived in London, with their son and daughter, Simeon and Rebecca. Harriet moved back to Oxford after she was widowed in the mid-90s. She continued to work as a senior administrator at the University, most notably in the Department of Materials Science, before taking early retirement. She lived happily in her little house in Jericho for 25 years, and maintained strong connections with people from her school and college days.

In later years, when her ability to see or to walk very far was much reduced, and she suffered increasingly from ill health, Harriet was even more grateful for these wonderful connections and friendships. Particularly during the pandemic, engaging with the online events and with her friends on Zoom was a real lifeline for her. Her family and friends remember her as a kind and generous woman with a keen mind and an excellent sense of humour.

Rebecca Fishman, daughter

HARRIET FISHMAN

Lesley Frances Coggins (Watson, 1962)

Lesley was born on 1 June 1943 in Bedford, where her parents had been evacuated during the war. Her father Harry played the horn in the BBC Symphony Orchestra and her mother Winnie was a skilled seamstress and bicycle mechanic. Lesley was brought up in Bedford Park, Chiswick and came up to Somerville in October 1962 from Notting Hill and Ealing High School on a Beilby Exhibition to study Zoology. She very much enjoyed her time at Somerville, making many lifelong friends and keenly engaging with the many opportunities open to undergraduates. For example, she was active in the United Nations Association (Cosmos), inviting the rising political star Shirley Williams as a speaker, and in 1965 became the cox of the Oxford University Women’s Boat Club for which she gained a Full Blue by participating in the annual race against Cambridge.

Lesley won a scholarship to study for a PhD in Cell Biology at Yale University. After graduating in 1970 she married John Coggins, whom she had first met when they were undergraduates in Oxford, and they both took up postdoctoral fellowships in the Biology Department at Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island near New York. They returned to the UK in 1972, settling briefly in Cambridge, where Lesley was a Sara Woodhead Research Fellow at Girton College. They moved to Glasgow in 1974, Lesley to a staff position at the Beatson Institute for Cancer Research. After 22 years leading the Electron Microscopy Group at the Beatson, Lesley embarked on a new career. She was recruited to set up a Cell Biology

Laboratory at the Glasgow University Biotechnology spin-out company Q-One Biotech. Over the years the company grew and morphed, eventually becoming BioReliance. Lesley retired as the Manager of Cell Biology in 2009.

Although her career was very important, Lesley had many interests beyond work. She loved learning in new areas, especially if they were intellectually challenging. Very knowledgeable about astronomy, she owned an impressive seven-foot-high reflecting telescope. She enjoyed coaching children in the local Scout and Brownie groups for their astronomy badges. She travelled to see many solar eclipses, and in January this year was very pleased that her son arranged for her to visit the Australian National Astronomical Observatory.

Lesley had a great love for archaeology and history throughout her life, and to complement this learned to read Egyptian hieroglyphics and to speak Mandarin. Together she and John visited many archaeological sites in Turkey, Italy and China, and in 2019 joined the 14th Pilgrimage to Hadrian’s Wall. Lesley conducted extensive research into her own family history, collecting many documents and photographs stretching back to the 17th century. She enjoyed spending time at the National Archives at Kew and visited many churches in Norfolk and Devon seeking information about family members.

Lesley was very much involved with the local community in Bearsden in Glasgow where she lived for almost 40 years. She was for more than 20 years the Secretary of Bearsden East Community Council, taking an active part in promoting local issues. She was also prominent in the East Dunbartonshire Liberal Democrats, organising visits from eminent speakers such as Paddy Ashdown, Shirley Williams, and Vince Cable.

Lesley also loved travelling, a passion that grew during her time at Somerville. During her Oxford summer vacation in 1965 she backpacked through Turkey and Greece with John and a group of her university friends. She very fondly remembered this holiday, including the part when they were all very nearly arrested for illegally crossing from Turkey to Greece in a fishing boat at night! Lesley also enjoyed sailing, a hobby she took up with John when they lived on Long Island and continued to pursue on the west coast of Scotland after moving to Glasgow. She also went on countless family holidays to the Mediterranean, the United States and more recently to Indonesia, China, Tanzania, and Australia.

Lesley was immensely proud of her two children and four grandchildren (with a fifth one on the way). Her son Andrew is an Emergency Medicine Consultant in Sydney, Australia, and her daughter Julia, who lives in London, is a Patent Attorney specialising in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. She particularly loved taking her children and grandchildren on holidays and to the museums and art galleries that she herself enjoyed.

John Coggins

LESLEY COGGINS

Barbara Cordelia (Cordy) McNeil (Collins, 1962)

Cordy McNeil passed away suddenly but peacefully in hospital on Thursday 14 April 2022. She had been admitted to hospital unexpectedly a few weeks before with an illness.

Cordy was born in 1944, in Northwood. She grew up in the Hampstead Garden Suburb, to which she always felt a strong affinity. She formed lifelong friendships at Somerville, where she was an Exhibitioner in History. Her tutor Agatha Ramm’s Germany 1789-1919: A Political History and an ever-growing library of history books were on the shelves of each home she made. She was delighted that her granddaughter Courtney, reading German at St Hilda’s, had been to seminars at Somerville. She met her husband, Andrew, performing in a play in the St Catherine’s JCR.

After graduating she joined the Foreign Office, working in the Information Research Department. But Foreign Office rules at that time meant she had to resign when she married. As a mother to Rupert, Charlotte and Emma she was full of fun and love. A love she went on to share with her grandchildren Sam, Courtney, Aodan and Owen. She would often say she was ‘just a mother’ but this was far from the truth. She taught English as a Foreign Language, was a trained counsellor* and befriended and took caring responsibilities for so many people in her family and beyond.

CORDY MCNEIL WITH HER GRANDCHILDREN

She was heartbroken when Charlotte died but pledged that it wouldn’t break her as it wouldn’t be fair to her memory or to her surviving children and grandchildren. When Emma moved to Northern Ireland she and Andrew decided to join her. They both enjoyed this new adventure exploring the countryside and enjoying their seaside location. During one of her final conversations with Emma she said how much love she had for the people in her life and the different phases of it.

*On the first day of training the tutors asked what her husband did for a living. She told them this was irrelevant and vowed to never mention it. She didn’t. For three years. A mark of how stubborn and principled she could be.

Rupert McNeil

Claire Janet Tomlinson (Lucas, 1963)

Claire Tomlinson was the highest-rated female polo player in the world and widely regarded as the greatest female player of all time. She captained the English team and subsequently coached it. She was the Chairman of the Beaufort Polo Club and taught Princes William and Harry to play. Numerous obituaries have appeared in the national press:

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/claire-tomlinsonobituary-wszlgcgrm

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2022/01/25/ claire-tomlinson-glass-ceiling-smashing-polo-player-taughtprinces/

This is a personal memoir from Claire’s Somerville contemporary and friend, Dr Maggie Mills (Smith, 1963): Claire came up to Somerville in 1963 to read Agriculture and Economics. In those days the women-only College shut its gates by 10.00pm.

My great good fortune was to sit next to Claire on the front staircase on our first night while we waited to meet the Principal, Dame Janet Vaughan. She greeted Claire, saying, ‘Yes, of course, you are our star and only polo player, and, I am told, much, much better than all the men.’ And how right Dame Janet was. Claire’s recent obituary in the Daily Telegraph called her ‘the greatest female polo player of all time’. Determination was a serious trait of Claire’s, so she got the men-only rule removed in double quick time and played her first Varsity match in summer 1964. To her chagrin, she was entered for the match as ‘Mr Lucas’. By the time she got her polo half-blue in her third year, no one doubted her formidable ability as a woman on the polo field. But none of her Somerville contemporaries knew what a talented athlete she was and that she had achieved a squash, a fencing and, extraordinarily, a ploughing blue as well. She was modest and never talked about it or drew attention to all she did. Only someone as relentlessly well-organised as Claire could have achieved her sporting successes, acquired a decent degree, and found time for so much fun and laughter with her friends. Her style reminded me of descriptions of the Thirties ‘bright young things’, always up for an escapade, including punting picnics on the river, croquet contests in college gardens which, not surprisingly, Claire usually won, and early morning exercising of polo ponies. I never knew how and when she got her academic work done. But I remember Claire marching off to an early evening tutorial, throwing me some avocado pears as she left and asking me to prepare them for our supper party later. This was the early sixties. I was not sophisticated. I had no idea. Not wanting to disappoint I telephoned the Elizabeth restaurant opposite Christ Church for help. When I told Claire later, she roared with laughter. She was generous-hearted and I owed her an education in so many ways. She was also fearsomely brave. Out with the Oxford drag

CLAIRE TOMLINSON

hunt, I once saw her jump a five-barred gate in three strides from a standing start – muttering as she went, ‘In for a penny, in for a pound.’ I admired the uncompromising way she always looked after the animals in her care: if you didn’t come up to standard you very quickly discovered Claire didn’t suffer fools – at all. I don’t think it ever occurred to Claire that there was anything you couldn’t do if you felt passionately enough about it. And nothing was too much trouble. And though the polo world might not seem a uniquely Oxfordian pursuit, look at all she achieved for gender equality and British polo excellence. She truly was magnificent. What I haven’t forgotten is Claire when she fenced. As well as having a blue she was seriously considered for the Olympic team. It was fierce, even alarming, but she was mesmerisingly graceful.

Kathryn Patricia Moir Wilson (Cave, 1966)

Kathryn (Kate) Wilson was born in Aldershot in 1948. Her parents, Harry and Eve, had grown up in Belfast, which explains why Kate associated the Belfast accent not with Ian Paisley but with ‘kind uncles who would give me half-a-crown’. Kate’s mother was a teacher and her father was a defence scientist and, after Kate started at Aldershot County High School, the family moved to his Washington Embassy posting in 1962. Kate’s three siblings, including Deirdre (Somerville 1961), were somewhat older and perhaps her feelings of isolation as a child, with a string of imaginary friends and fantasies, laid the foundations for her later writing. After three years at school in the States, Kate was sent back to England to attend the sixth form of Wycombe Abbey. Her school friend Yvonne Whiteman recalls: ‘Kate arriving at Wycombe Abbey when I was feeling particularly cheerless and friendless, bringing with her the Beach Boys, The Lord of the Rings, Nietzsche and Lawrence Durrell. Suddenly the world lit up.’ Kate and her friends were ‘like-minded teenage rebels’, attending Beatles and Stones concerts and dancing in cellar jazz clubs when they could escape ‘the 18th-century Gothic walls of our ladylike boarding school’.

At Oxford, Kate was still a party lover who always enjoyed ‘dancing my socks off’. She read PPE at Somerville; after graduation, she spent a year studying philosophy at MIT. She married Martin Cave in 1972; in 1974 they moved to Uxbridge – Martin had an economics lectureship at Brunel University – and they brought up their children Eleanor, Joe and Alice there, with spells in the USA and Australia. Kate somehow found time to become an ace tennis player as well as being a super-dedicated and loving mother.

Although she followed Martin’s career in terms of location, Kate had highly portable interests and talents – editing and, most notably, writing fiction. From 1984 onwards, she published many inspirational books for children. In 1994 Something Else, illustrated by Chris Riddell, was awarded the first UNESCO Prize for Children’s Literature. Still in print, in many languages, it has sold well over a quarter of a million copies. Maurice Lyon, her editor at Penguin Books, writes: ‘she was a very special writer with an acute eye for the way children see the world. It was a great joy and privilege to work with her on Something Else. It’s the book I am most proud to have been associated with. Her books have that wonderful quality of being able to make you laugh out loud at the same time as being profoundly moving. Kate leaves a wonderful legacy of writing and is a real loss to children’s literature.’

While pursuing her writing career, Kate was also an editor at Frances Lincoln – Frances (Somerville 1964) was a close friend. Her most arduous achievement was editing a new edition of Wainwright’s Walks – all seven volumes – and undertaking many of the Lake District walks herself to get a closer insight. Kate loved walking, with family, with friends, or alone: she regularly walked on nearby Primrose Hill and Hampstead Heath, even during her illness.

The moral of Something Else, that we should embrace difference, was central to Kate’s personal philosophy. Her compassion and hatred of injustice, cruelty and intolerance were expressed in her volunteer work for the Samaritans and for refugee charities.

Kate had exceptional inner resources and determination, qualities much needed when she was diagnosed with lung cancer in 2014. She resolutely chose a rigorous diet and alternative therapies then, later, innovative NHS treatments at the Royal Free Hospital. Thankfully, and remarkably, she was able to enjoy seven more years with family, friends and her beloved grandchildren. She died peacefully at home with her family on 3 December 2021.