3 minute read

WOMEN WHO HAVE SHAPED THE SEB

BY REBECCA ELLERINGTON

The SEB has played a significant role in shaping the field of experimental biology over the past century. While the contributions of many notable male scientists to the SEB are well documented, the pivotal role played by women in the Society’s development and success are sometimes overlooked. In this article, we will explore the lives, research and contributions of some of the pioneering women who have helped to shape the SEB, from the early days of the Society’s formation to the present day.

Marie Victorie Lebour, a British marine biologist born in 1876, made significant contributions to the study of marine life in the early 20th century. Her pioneering work in the field of marine biology helped to lay the groundwork for modern oceanography. Born in Northumberland, England, Marie was the youngest of three daughters in a family with an appreciation for nature. Her father, George Lebour, was an accomplished artist and prominent geologist. Growing up, Marie cultivated an interest for the natural world while accompanying her father on his geological excursions, ultimately inspiring her own career.

After initially studying art, Marie began working at Durham University as a demonstrator in the Department of Zoology from 1906 to 1909. During this time, she pursued her BSc and MSc in Zoology and later became a lecturer at the University of Leeds while earning her doctorate. Even before receiving her formal education, Marie had already begun her research career, publishing her first paper in 1900 on land and freshwater molluscs.

Following her doctorate, Marie worked at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth, England, where she remained for her entire career studying the ecology and physiology of marine animals. She focused primarily on marine invertebrates, microplankton, crustaceans and molluscs and made several significant discoveries, identifying 28 new species of microplankton and helping to establish the importance of plankton in the marine ecosystem. Her background in art proved useful, and she created illustrations and watercolours for her research publications.

In addition to her research, Marie was also an active member of the scientific community. She was amongst the first cohort of scientists who joined the SEB in 1923 to collaborate and exchange ideas. Her involvement in the SEB helped to further establish her reputation as a leading figure in the field of marine biology.

Marie passed away on 4 March 1974, yet her legacy in the field of marine biology continues to be felt today. Her contributions have helped shape our understanding of the oceans and the delicate balance of life that exists within them. She was a trailblazer in a field dominated by men and is an inspiration to aspiring marine biologists around the world.

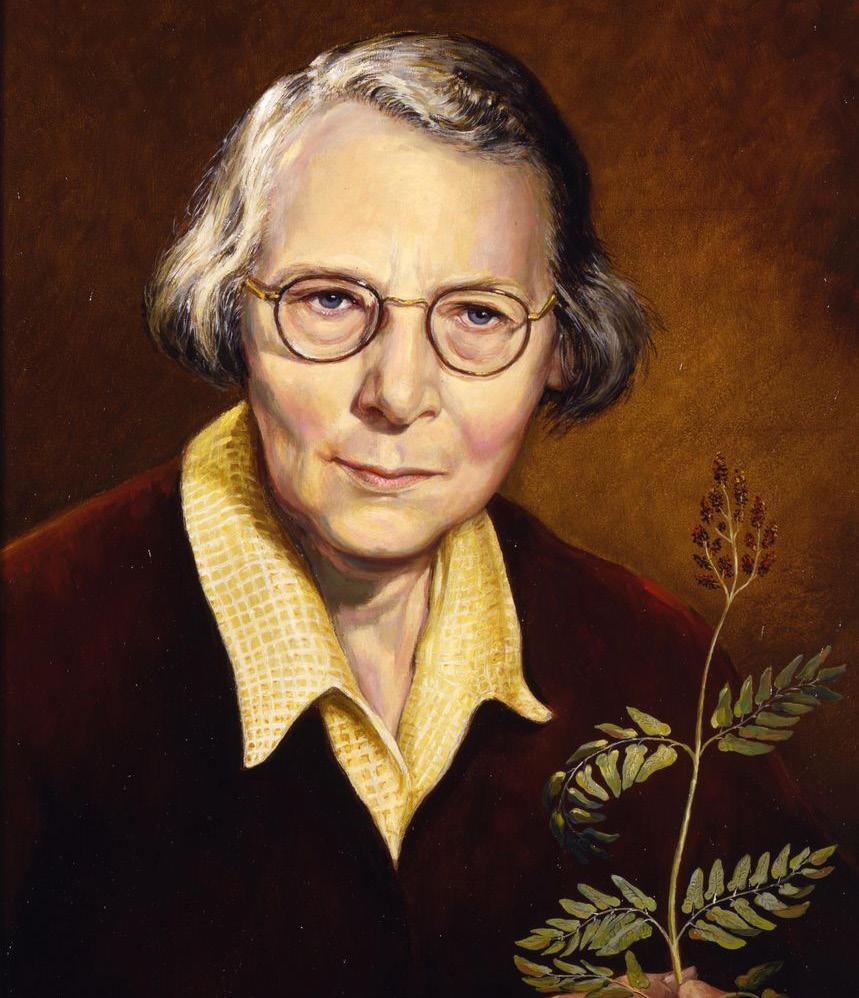

IRENE MANTON (1904–1988)

Irene Manton was a British cytologist who was born in London. Her father, a dental surgeon, introduced her to a microscope, and her mother encouraged her and her sister to take an active interest in natural history. At school, Irene developed a passion for and, despite the staff considering her idle and encouraging her parents to remove her from school to pursue music, she passed the school-leaving examination with ease, winning a Clothworkers Scholarship to Cambridge to study Botany.

After reading the work of Edmund Beecher Wilson, Irene decided she wanted to pursue a career in plant chromosome cytology. In order to achieve this goal, Irene sought advice from cytologist Dr Kathleen

Blackburn and palaeobotanist Dr Hamshaw Thomas, who recommended Professor Otto Rosenberg’s laboratory in Stockholm, Sweden. There, Irene began her early work using chromosome number to elucidate interrelationships between plants and their phylogeny.

In 1929, Irene joined the Botany Department at the University of Manchester as Assistant Lecturer. She worked under the supervision of Professor W.H. Lang, who instilled in her the importance of recording microscopic observations through photography and using fresh plant material. Lang encouraged her to switch her research focus to ferns, a subject she would continue to study for the rest of her career. She later developed the “squash method”, which allowed for more accurate chromosome counting in ferns, and helped to establish that accurate chromosome counting is vital for characterising species and for phylogenetic classification.

Irene was not only a brilliant scientist, but also a generous contributor to the scientific community. She was deeply involved with the SEB, serving on the Council during the 1950s and presenting at numerous SEB conferences. Beyond her research and service to the SEB, Irene was a gifted mentor and educator, inspiring and training young plant biologists. Her enthusiasm, meticulous attention to detail and contagious energy left a lasting impact on generations of postgraduate students.

Apart from her scientific career, Irene had a wide range of artistic interests. She was passionate about music and played the violin to a high standard and collected Chinese and modern art. Irene continued to pursue both her leisure and scientific pursuits into her retirement before passing away on 13 May 1988.

Irene’s legacy in the field of plant biology and as an advocate for young biologists is honoured by The Irene Manton Poster Prize, awarded annually to the best poster presentation by a young scientist at the SEB’s Annual Conference.