13 minute read

ORIGINS OF THE LIVING FIELD

Geoff Squire, the founder and editor of Living Field, recently joined a working group of the SEB whose remit is to develop outreach, education and diversity. Here he writes about his experience in the Living Field project, based at James Hutton Institute, Dundee, UK. But first, some appreciative recollections of the SEB’s influence on his earlier work linking biological process to regional and global sustainability.

The SEB has for decades given encouragement and opportunities to early-career researchers, in my case first as a doctoral student with Terry Mansfield at Lancaster University and then throughout a long association with John Monteith, Mike Unsworth, Paul Biscoe and colleagues at the University of Nottingham. The group there comprised mostly physicists, but supported an array of postdocs and students from other disciplines. The pervading ethos was ‘different therefore equal’ – a group ethic that strongly influenced my subsequent collaborations across disciplines and continents.

Advertisement

It was an exciting time at Nottingham. The ‘big leaf’ theories of measuring and modelling environment flux were instructive at certain degrees of scale and complexity – large flat areas of uniform vegetation – but some physicists and biologists sought to apply flux-based approaches to finer assemblages of functional types and individual organisms. The main generic question being asked was ‘how do differences between individuals propagate through time and space to affect the properties of populations, landscapes and ecosystems’, and, in reverse, ‘how do the characteristics of large scales constrain the possibilities for individual performance’.

In the early 1990s, I joined a group of physicists and biologists at the then Scottish Crop Research Institute (SCRI), now named the James Hutton Institute (JHI). The team’s interest, like mine, was on the individual in the group – individuals being ‘different therefore equal’ – in terms of the need to include them in experiments and models. Crucial to the development of the subject was the 1994 SEB seminar Scaling Up: from Cell to Landscape, published in 1997 as SEB Seminar Series 63.1 The whole debate and its intricacies around up-scaling gave such a buzz at the time and has been an influence that remains to this day.

ORIGINS OF THE LIVING FIELD

The issues in up-scaling from experimental chambers, plots and fields to catchments and landscapes became a major part of the work at SCRI/JHI. Understanding, and then predicting, the consequences for ecosystem function of many small plant-by-plant or field-by field changes continued to be challenging, whether directed at reducing further loss of biodiversity or ensuring food security in uncertain times.

It was evident from SEB Seminar Series 63 and subsequent spin-off debates that biophysical science had to incorporate social, economic and political science if it were to make progress with global challenges. It was not enough to say ‘here’s the biophysical, now you get on with it’.

In this melee, two distinct influences led to the formation of the Living Field. One was the uncertainty in public understanding of genetic modification (GM) and gene flow, topics that intensified in the late 1990s with the beginning of large-scale GM crop trials in the UK (e.g. the Farm Scale Evaluation projects2,3). Several of us at SCRI ran gene-flow roadshows, at the Edinburgh Science Festival for example, but when talking to people on these issues, it was clear that much more information, and more accessible information, was needed on things like soil, plants, microbes, functional biodiversity, food webs and the movement of living things across a landscape.

The second influence was more of a jolt. At a scientific meeting in the late 1990s (not SEB!), the view was promoted by some that modern agricultural fields need be nothing beyond dead, industrial deserts. Such a position had already gained widespread acceptance in some countries and was permeating UK agriculture. That fields could be dead and productive was impossible, yet many agricultural interests were heading that way. So ‘No Dead Desert’ was a possible title, but I settled on the more positive ‘Living Field’.

Left One of the display boards in the Living Field garden. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

Left Below Collage of habitats, plants and small animals crafted by photographer Stewart Malecki and Gladys Wright soon after the Living Field garden was opened in 2004 to emphasise that agricultural land was ‘no dead desert’. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

THE LIVING FIELD GARDEN AND STUDY CENTRE

Though the name was coined in 2001, the direction and scope of the project evolved gradually. Unfunded at first, ideas and physical labour were given freely by staff and students. One of the first challenges was the need for a physical base – a place to grow and nurture plants and their attendant microbes and animals. Most of this space had become so scarce that few people were able to see, on a walk or drive, no more than a small fraction of the biodiversity that once thrived in the croplands.

The Institute provided a small area of land that farm and science staff converted to microhabitats – meadow, woodland, hedgerow, pond and ditch – and areas for growing crops, including those current and the many species that had once been farmed or gathered but were no longer appreciated, grown and used. Among the latter were ancient cereal species and landraces, forage legumes, dye plants, fibres, medicinal plants and useful ‘weeds’.

The Living Field garden was formally opened in 2004.4 Since then it’s been accessible to the public at all times. Within a few years, the garden came to support hundreds of plant species, many of which came in of their own accord, finding space in the low-input meadow, for example.

The assemblage of plants and associated invertebrates allowed a sort of scaling over time (as well as space); people could see the crops and useful wild plants that were once grown, the contraction to the ones now grown and the potential of those that could be grown or encouraged in future regeneration. And the presence of real plants provided opportunity to scale down, for example to show how species differed in fine root structure and function and to examine the plant–rhizobia symbiosis in nitrogen-fixing legumes.

STAFF AT THE INSTITUTE GAVE THEIR TIME FREELY ON MANY OCCASIONS TO BRING SCIENCE TO PEOPLE, FROM THE VERY YOUNG TO THE LESS YOUNG.

The need to regulate environmental fluxes was demonstrated through the nitrogen cycle: biologically fixed nitrogen pollutes very much less than mineral fertiliser, and gives highly nutritious forages and food. A range of forgotten forages and crops were grown at the Living Field (white melilot, sainfoin and kidney vetch shown), their positive role in the food web demonstrated, and links made to the Institute’s science on the underlying plant–bacteria symbiosis and nitrogen fixation.

OUTREACH – EDUCATION – DIVERSITY

Outreach, education and diversity (OED) have not been intentionally distinguished in the Living Field project. Perhaps the main drive was outreach to schools and to the wider community. Through early experience, Gladys Wright5 and other contributors instilled the practice at open days and roadshows to cater first for primary age children. If they were happy and occupied, then their older relatives and friends could immerse themselves in the exhibits and talk to staff. Events in the garden, for example, always had a ‘finding’ or ‘making’ game for children,

Above Linking flux to food: nitrogen cycle, symbiosis (micrographs by Euan James), forgotten forages, food webs, nutritious pulses. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

then more thoughtful exhibits for grown-ups. Staff at the Institute gave their time freely on many occasions to bring science to people, from the very young (fascinated by oat grains) to the less young (debating future life on the planet).

A consistent method of working took hold in which an initial scientific object – perhaps of little interest to the public in itself – was explored through activities that visitors could be part of and themselves develop. Artists and craftworkers from the wider community were encouraged to become embedded in the Living Field to foster this extension of an initial object or thought.

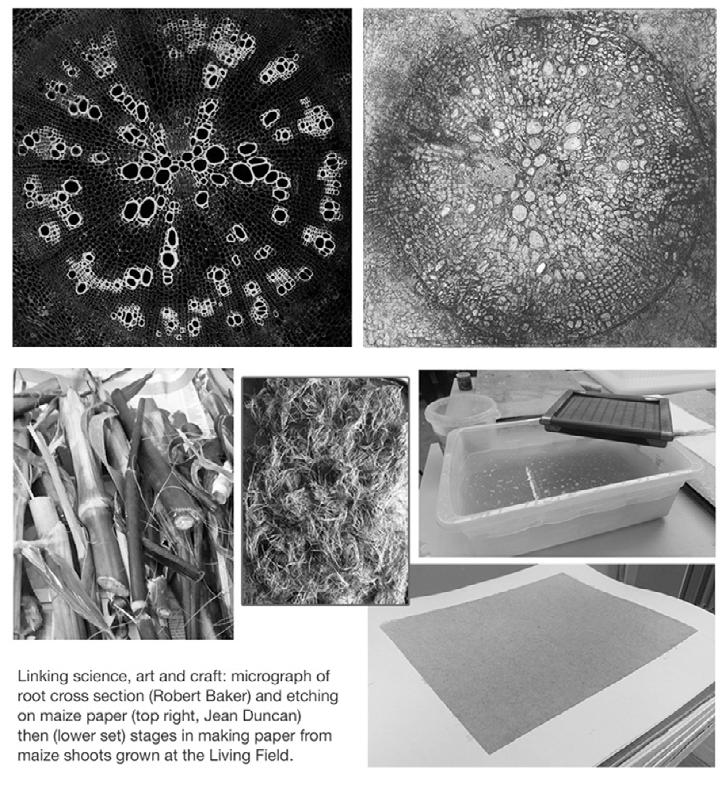

One example is the artist Jean Duncan’s depiction of roots and seedlings – an original root section was used as a model for a series of etchings that were printed on paper made from plants grown in the garden.6,7 A path could be traced from the growing, touchable plant and its structure (e.g. fibres) to the process of converting the structure to something useful (e.g. paper), and finally design and printing on the paper of attributes crucial to the plant’s functioning and survival (xylem, phloem, etc.). Another example includes cyanotyping to reveal form and texture, colouring with plant dyes and working the stages from grain to plate (or seed to sewer as some liked to call it).

Left Exhibits, roadshows, open days by the Living Field – bringing the buzz of science to people of all ages. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

Bottom Left Linking science, art and craft: micrograph of root cross section (provided by Robert Baker, Department of Botany, University of Wyoming, with thanks) and etching on maize paper (top right, Jean Duncan) then (lower set) stages in making paper from maize shoots grown at the Living Field. Source www.livingfield.co.uk The are also some big questions on the origin of food – is it local or imported, and if imported where does it come from? To show what’s grown locally, the farm and science staff constructed a map of Scotland in the Living Field garden and in 2019 planted it with a range of food crops in locations where they are typically grown. It certainly caused some discussion.

UNIVERSITY EDUCATION

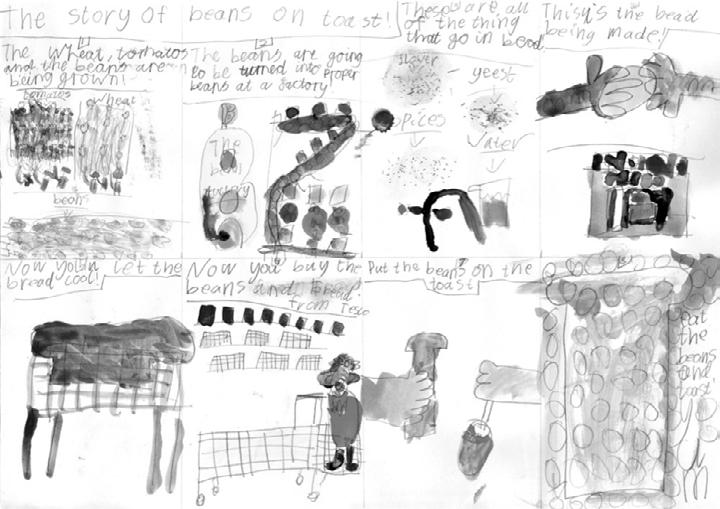

University education, though not a primary aim, was fostered through visiting students and project work. While many MSc and PhD students based at the Institute contributed at open events, some worked more directly on specific projects. For example, a student from Durham University, Sarah Doherty, spent almost a year at the Institute working on food systems, especially the Beans on Toast project which dissected the constituents of this meal and traced the geographical origins and water footprint of the 10 or more crops that go into it.8,9 She devised a Beans on Toast roadshow for primary schools, from which it was clear to see that such young minds could appreciate complex food supply chains. In drawings, some of the children depicted beans as individuals rather than a mush – an appreciation of the ‘individual in the group’ perhaps?

In other work, a group of students from Abertay University in Dundee worked with scientists in seed ecology and morphology to construct a key to weed species, based on shape, colour and texture of seeds and seedlings. The key was

Top Left Is my food grown near me? Map to scale made of turf and boulders planted with food crops – a hit with visitors. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

Left From the Beans on Toast Roadshow: one of a set of diagrams drawn by primary school pupils of the supply chains leading to this prized dish. Source www.livingfield.co.uk

used online by the public and arable seedbank researchers for many years. A student visiting from AgroParisTech, Marion Demade, used her drawing skills to illustrate Reno the Fox’s musings on modern life, persecution and land use.

DIVERSITY AND INCLUSION

Diversity was not considered specifically, but in retrospect, it was there from the beginning. Essential contributions were made by colleagues from all parts of the Institute – from farm, glasshouse, graphics, technical and scientific interests. The farm and science staff built the garden from scratch and constructed the real ‘Vegetable map of Scotland’ along with mountains and coastlines.10,11 And it would have been impossible to show visiting school parties how potatoes are grown and harvested without a command of modern agronomy and farm machinery. Looking back, the cultural attitudes at SCRI and subsequently JHI were conducive. Everyone, from all backgrounds and grades, used first names – there was no social distancing.

The same attitudes guided the project’s many external links and interactions. An online and CD-based study course for the 5–14 age range was released after months of joint work between school teachers, institute science staff and graphic designers. Local radio stations and BBC Scotland arranged to record ‘voice-overs’ – spoken word accompanying the text and diagrams – and interviews with schoolchildren in their vernacular, which made the scientific and logical threads of the course more accessible to the intended users. All were given equal credit; the photographs show some of those involved.

The world of OED has changed in the past two decades. Two forces in particular will influence its future. One is the presence and sophistication of online communication and gaming. The other is a raised awareness, particularly among the young, of the perilous state of the world’s ecosystems, especially those dominated by agriculture or forest extraction. Many people with interests in future sustainability expect guidance from science but want to be part of the solution – and the communication and learning must be hi-tech.

And with some coincidence, a new project run by SEDA Land takes off in 2022 that will look at local versus external sourcing of food and other natural products.12,13 It will develop through collaboration between a community development trust, scientists (biophysical, social, economic and political) and high-level computer gaming expertise from Abertay University. Yet despite virtual opportunities, contact between people and real plants, their habitats and associated biodiversity will remain crucial. Activities in the Living Field garden ceased during the pandemic – but Living Field’s or something like them are needed everywhere.

References:

1. Van Gardingen PR, Foody GM, Curran PJ (eds). Scaling-up: from Cell to Landscape. Society for Experimental Biology

Seminar Series 63. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1997. 2. Firbank LG, Heard MS, Woiwood IP, et al. An introduction to the Farm-Scale Evaluations of genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops. J Appl Ecol 2003; 40: 2–16. 3. Squire GR, Brooks DR, Bohan DA, et al. On the rationale and interpretation of the Farm Scale Evaluations of genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B

Biol Sci 2003; 358: 1779. 4. The Making. www.livingfield.co.uk/living-field-garden/themaking/ 5. From a Muddy Field. www.livingfield.co.uk/home/about/ from-a-muddy-field/ 6. Sectioned II. 2019. www.livingfield.co.uk/art/jean-duncan/ sectioned-ii/ 7. Jean Duncan Artist. www.livingfield.co.uk/people/jeanduncan-artist/ 8. Beans on Toast – a Liquid Lunch. 2019. www.livingfield. co.uk/5000-plants/legumes/beans-on-toast/beans-ontoast-a-liquid-lunch/ 9. Beans on Toast Revisited. 2019. www.livingfield.co.uk/food/ pulse/beans-on-toast-revisited 10. The Vegetable Map Made Real. 2019. www.livingfield.co.uk/ food/vegetable/vegetable-map-made-real/ 11. Can We Grow More Vegetables? www.livingfield.co.uk/food/ can-we-grow-more-vegetables/ 12. Scottish Ecological Design Association. SEDA Land. www. seda.uk.net/seda-land 13. Community Mapping – Food, Climate. 2022. http:// curvedflatlands.co.uk/land/community-mapping-foodclimate/

Author/contact: The author acknowledges with thanks the opportunity to join the SEB’s Outreach, Education and Diversity focus group. Email: geoff.squire@hutton.ac.uk or geoff.squire@ outlook.com. Footnote: The phrase ‘different therefore equal’ comes from the title and song of an LP: Seeger, Peggy. Different Therefore Equal. Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, 1979. Left Recording The Living Field 5–14 online course. Source www.livingfield.co.uk