2 minute read

The Rise of the Magic Valley

By Sandy Pollock - Museum of South Texas History

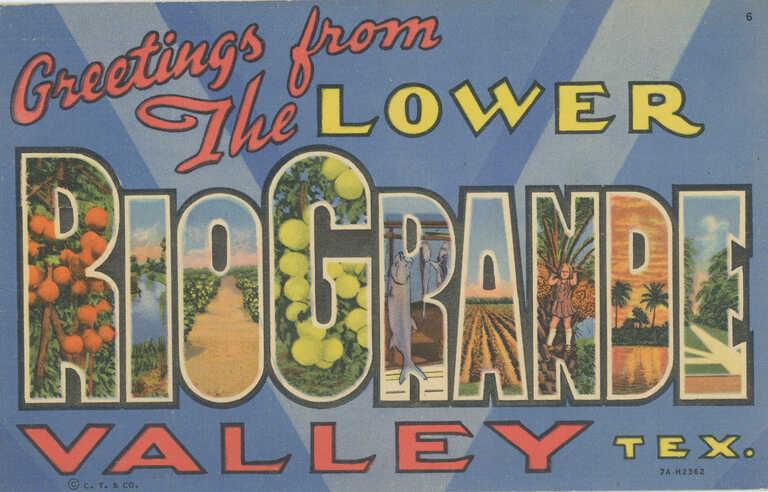

In the early 20th century, a bold vision transformed the Lower Rio Grande Valley of South Texas into what would become known as the “Magic Valley.” This rebranding was not just a catchy phrase—it was a carefully constructed place myth designed to lure settlers, sell land, and promise prosperity. But behind the imagery of citrus groves and irrigation canals was a calculated campaign driven by land developers, railroad companies, and chambers of commerce.

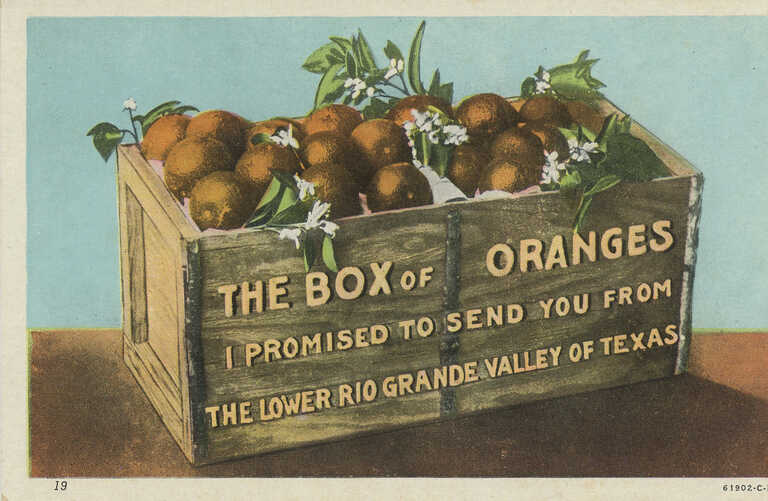

Before the arrival of the railroad in 1904, the Valley was largely viewed by outsiders as remote, arid, and undeveloped. That perception began to change with the construction of irrigation systems and a surge of promotional literature promising fertile farmland and year-round harvests. Developers described the area as a tropical paradise— “a Garden of Eden” where anyone could farm successfully with little effort. These promotions, often illustrated with images of flourishing crops and palm-lined roads, offered a dramatic contrast to the region’s semiarid reality.

Central to this myth was the idea of transformation: wilderness to farmland, desert to abundance. Water could be "telephoned" in by irrigation, and the land—once considered untameable—was now depicted as ripe for settlement. Developers like John Shary played a pivotal role in marketing the region through pamphlets, maps, and orchestrated “home-seeker” tours. These excursions presented a curated version of life in the Valley, showcasing progress while shielding potential investors from the struggles faced by local laborers.

Labor, particularly from Mexican and Tejano communities, was a key element in this transformation. Promotional materials often emphasized the availability of “cheap and dependable” workers, casting them as both essential and invisible in the grand narrative of Anglo prosperity.

By the 1920s and 1930s, the myth evolved to promote the Valley not only as an agricultural opportunity but also as a lifestyle investment. Citrus groves, paved roads, and social clubs began symbolizing profit and prestige, attracting urban investors alongside farmers.