11 minute read

Fresh Perspective

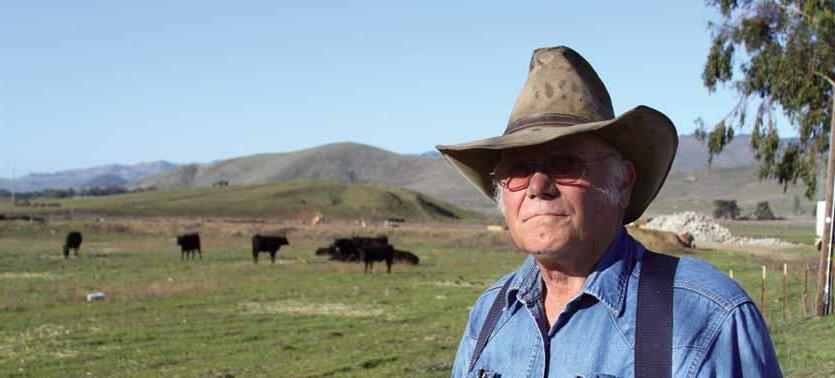

Dan De vaul

Upon losing his appeal, an uncertain future awaits.

BY MARISA BLOCH

A little more than a year ago, when he was found guilty on charges of illegally housing tenants on his property, Mary Partin, a juror – one of twelve that had voted to convict – turned around and bailed him out of jail the next day using her own personal funds. Partin later told reporters that she “regretted her guilty votes and wanted to help him.” We wanted to know more about the man who had inspired such unusual behavior and stirred what must have been a powerful mixture of feelings and empathy within a perfect stranger. At the same time, we were looking for a fresh perspective for this much-told story, so we decided to dispatch our own Cal Poly intern and journalism student, Marisa Bloch, to have a look around Sunny Acres. Here is what she found… As I pulled off of Los Osos Valley Road and drove into the dirt driveway of

ASunny Acres Ranch on a crisp Friday morning, my eyes moved from wine barrels, to piles of wood, to broken-down cars and machinery, and finally to an old barn/house. A small sign with the word “office” along with an arrow directed me to my destination. I came to a stop in what seemed to be a parking spot, an empty space between a line-up of old cars - some looking as if they hadn’t run in years. I stepped out of my car, not sure what to do next. There were no signs directing me toward the office, but instead before me stood an old, falling down barn, complete with chickens and roosters. There were people diligently going about their daily work, and none of them stopped to acknowledge my existence. As I looked around somewhat perplexed, I thought, “What have I gotten myself into?” Just then I heard a woman yell out from a balcony above me, “Someone’s here! She’s a young girl and she just got out of her Honda.” There was a pause, and then she said to me, “He’ll be right down.” The “he” she was referring to was 67-year-old rancher, Dan De Vaul. De Vaul soon appeared in a doorway ahead and slowly began to amble toward me with a slight limp that, I would learn later, was due to partial paralysis resulting from an automobile accident back in 1970. He stood before me in his well-worn button-up long sleeve shirt, his dirty blue jeans held up by suspenders, and a beige cowboy hat that looked like it had never left his head. There was no smile on his face, no excitement to meet me. There was a gruff hello, followed by my short introduction. Then he led me toward his office, which was a little cubby-hole-of-aspace that was located next to where people were working on old cars. It was not a place to sit and contemplate quietly, as there was loud machinery going off all around us. Inside it was dark and furnished with nothing but two chairs, a desk, and a filing cabinet. There were papers strewn about along with a few random, scattered pictures. It did not appear as if De Vaul inhabits his office much. He is a rancher, after all, who spends a great deal of his time operating heavy equipment on the property. The Sunny Acres program, it seems, is a two-way street in that the residents are there to rehabilitate, but they also supply the labor at the ranch, which is important to De Vaul, especially since he has a lot of physical limitations. The people that participate in the program are required to pay $400 per month (recently increased from $300), which includes all of their room and board, and recovery meetings. The tenants have the opportunity to work off part of their fee by laboring on the ranch.

And, the residents have a wide variety of tasks to choose from. They can fix machinery, work on construction, assist with farming, cook meals, cut wood, make wine barrels, and much more. All of the residents’ hard work is what helps keep Sunny Acres going. De Vaul sells the wine barrel planters and firewood year-round, plus fruits and vegetables when they are in season, and pumpkins and Christmas trees at their appropriate times, as well. It was interesting to learn, however, that when I sat down to begin our interview I was not dealing with a simple rancher, as his appearance would indicate. De Vaul is surprisingly “media-savvy” and his first question to me was: “What’s your [story] angle?” Before I started into the interview, De Vaul had already begun rambling off what seemed to be his generic, prepared speech for the media.

He began by telling me that he was born and raised on the ranch, he had attended Cal Poly for a short time as well as Arizona State University. He had returned to San Luis Obispo to help his father run the ranch and, after he passed away, De Vaul took it over. But, my research told me all of this already and I was looking for something new – I was determined to understand the man and his motivations, but, first, I would have to wait for him to get through his monologue.

“We started running Sunny Acres in the late 90s’ but it didn’t become a non-profit until 2002,” said De Vaul. He asserts that, from the day he opened the facility, the County and State were both against it. “They said we couldn’t do it here. I wouldn’t give up. I was going to do it one way or another and that struggle still continues today.”

On February 18th, De Vaul lost his appeal and has vowed to continue the fight. “We will just have to appeal to a higher court like Ventura.” Next, De Vaul took me on a tour of the rest of the ranch in his white, stick shift, pick-up that was anything but shiny and new. I climbed in, the old engine rattled to life, and we took off to tour the parts of Sunny Acres that most people don’t see. I saw the accommodations they had built that were condemned. It was a two-story building with a couple of community bathrooms, a kitchen, several bedrooms, and a lot of open space. Now, however, it is solely being used for storage. Since the residents are no longer allowed to reside in the structure, they are now living in what look like little wooden bungalows, glorified sheds, really. They do fit two people, but it appears to be a tight squeeze. The modest accommodations are all furnished, carpeted, with new paint, and measure about eight feet by eight feet. At any given time, there are somewhere from 8 to 12 people that do not live in these little huts, but instead live in the comparatively comfortable farmhouse. De Vaul himself lives in the attic of the barn, which from the outside appears run-down and far from spacious. As we continued our drive around the property, De Vaul stopped to show me different things, as well as to resolve issues he would spot with the tenants - he called it “putting out fires,” which did carry more than a little bit of irony considering the actual fire that took place there in July of 2009. Without question, he is a stern man, who appears to strictly enforce the rules, which clearly has gained him the respect of all the people living on the ranch. During one of those unplanned stops, he checked in with a tenant who had been accused of consuming alcohol. De Vaul was quick to ask if the supervisor had brought out a Breathalyzer. De Vaul appears to take the program very seriously, and could not fairly be accused of coddling the residents. I scratched out a note, which read: “tough love.” Up to this point, De Vaul had been in interview mode, skillfully working down a mental checklist of talking points. He was going through the same routine, which I am certain he went through with all the other journalists that have visited the property. However, in a split second that all changed when the truck lurched to a sudden stop and a knowing smile crept onto his face. On the ground, no more than fifteen feet away, was a full-grown hawk locked onto its latest prey - a little gopher that was putting up a valiant struggle, but clearly was not getting away on this day. De Vaul turned to me and said, “That is a sight to see. Most people never get to see something like that.” It was a breakthough and, for the first time that day, I felt that I caught a small glimpse of the real Dan De Vaul. We continued on our drive and he showed me the kitchen, and all of the broken-down tractors and machinery. Although these machines are not pleasing to the eye, and look as if they won’t start, they are unique because, according to De Vaul, they all run and serve some purpose on the ranch. “My guys fix all of the equipment so it can run, and when it breaks down, they fix it again. They get to feel a sense of worth and responsibility,” he explained.

When we returned to the barn, I was able to sit down with Jess Macias, De Vaul’s second-in-command and an addict himself. He has been at Sunny Acres for nine years and insists that Dan has been a great mentor to him during that time. He confided that De Vaul is an authority figure, but that he usually gets across to people in the program in a way that [ ] others cannot and usually gains their respect. “He doesn’t have to do any of this for us. He doesn’t need the money. He could up and leave at any time, but instead he went to jail for us, and to fight for something he believes so strongly in,” said Macias. De Vaul does have a certain level of “street cred” with his tenants because he, too, is an addict. “I’ve been off drugs for about 30 years, off alcohol for about 20 years, and off cigarettes for about 15 years,” states De Vaul. He said he knows how it is to be in the state his residents are in, which is what he says motivates him to make Sunny Acres a successful program. He then pivots back into his sales pitch for Sunny Acres, claiming it is one of the cheapest programs out there with work, food, and a place to stay. “Since we have the space we don’t usually have to turn people away, and they can stay as long as they want, provided they follow the rules and contribute around the ranch.” De Vaul, finding his rhythm, takes it up a notch. “Most people that are against Sunny Acres either have a private axe to grind or they don’t have the information about what goes down here. People don’t realize that we haven’t had any trouble that has extended to our neighbors. We have had to call the police out here to arrest people because they are drinking or whatever the problem may be, but this hasn’t spilled over to the neighbors,” claims De Vaul. For the most part, the residents of Sunny Acres must stay on the property unless they need to leave for appointments. Otherwise, they are not out in the community but working on the ranch. As if to strengthen his pitch, De Vaul adds that he was “recently talking to a clinical psychologist in the field of addiction and recovery” and he relates that [the unnamed psychologist] stated that about half the homeless people in the area are veterans. “That’s shocking,” observes De Vaul. “In our wars in the past like Vietnam, we are not realizing the people we are messing up. And in Iraq and Afghanistan, once these people come home and try and adjust to everything else, that’s when the problem is going to hit.” De Vaul takes a deep breath, scans the horizon then continues. “I fight for this so much because I believe in this program and I have been there myself, but another part of me is just irritated now with the County, because they are continuing to fight me on this. I really enjoy what I’m doing. It’s my retirement. I wish I could get Sunny Acres to be selfsustainable so I can back off a bit. The program needs to grow a bit more, and get some of its problems worked out first. Gradually it’s all getting worked out and we are looking for a better day.” As De Vaul began to wrap up his pitch for Sunny Acres - his closing argument - my mind drifted back to the hawk that so thoroughly transfixed him earlier in the day. And, it occurred to me for the first time that, perhaps it wasn’t the hawk that De Vaul stopped to admire, but, maybe, just maybe, he was feeling some type of kinship with that little gopher who was putting up one hell of a fight.

resiDent housing

SLO LIFE