8 minute read

DWELLING

COHOUSING

TIERRA NUEVA

1

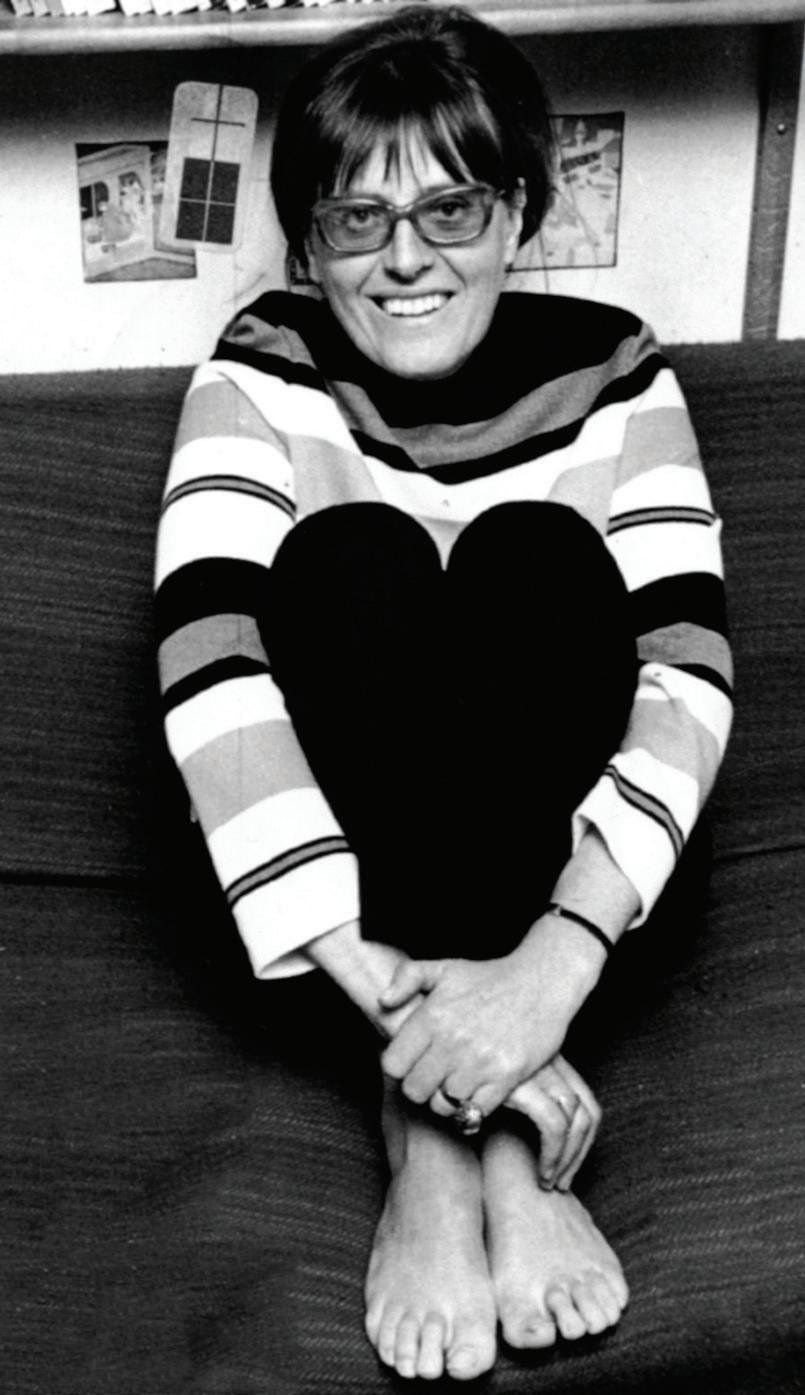

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MAREN BRAJKOVICH

A fascinating social experiment is taking place on a five-acre plot of land at the end of Halcyon Road in Oceano. With the ocean sparking in the distance, just beyond the dunes, 68 people are living together in a 27-unit complex that was built in 1999. Those people, ranging in ages from one-year-old to mid-eighties, have come together to live in a development known as “cohousing.”

People call it a village, and we know everyone.

My daughter knew everyone’s name by the time she was two, including all the cats and dogs, which is cool, you know?”

3 4

2

[ ]1. resident work day 2. neighbors visiting 3. feeding the community chickens 4. walkways everywhere, not a car in sight 5. village by design

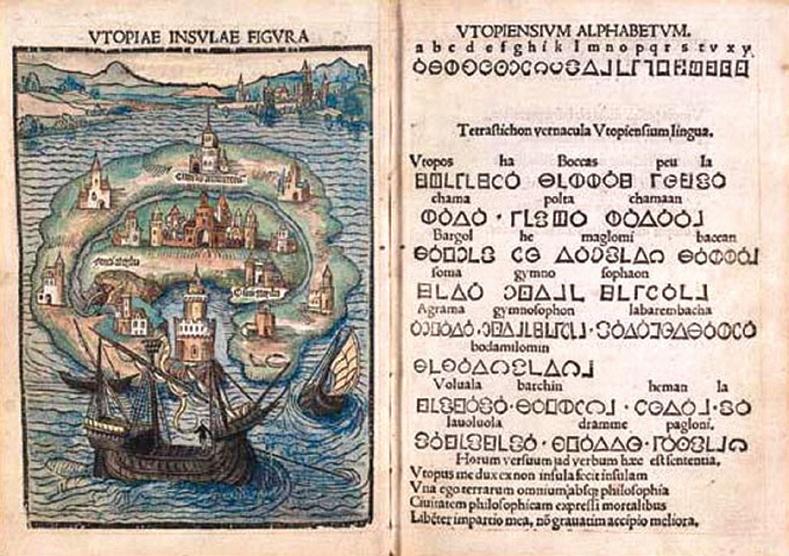

CCohousing, which derives from the term cooperative housing, originated in 1960’s Denmark. The roots of the concept are credited to Bodil Graae who wrote a newspaper column with the title “Children Should Have One Hundred Parents.” The piece resonated during that time and soon cohousing began spreading throughout Europe. The concept is simple, Tierra Nueva annual soda tasting event[ ] a group of families and individuals come together to create a type of intentional community, each one owning a private home which is supplemented by shared facilities and shared responsibilities. Although Graae is recognized as the catalyst for the modern day cohousing movement, its philosophic underpinnings can be found much deeper in history. The word “utopia” traces its roots back to the Renaissance. The English lawyer and philosopher Sir Thomas More first brought the concept to mainstream consciousness with his 1516 book called Utopia. The novel describes a fictional island society, which follows many of the same principles espoused by the Cohousing Association of the United States. The organization uses the tagline “Building a better society, one neighborhood at a time” and is governed by its “Six Defining Characteristics of Cohousing,” which are as follows: 1) Participatory process—everyone has a say; 2) Neighborhood design—ample open space to encourage community; 3) Common facilities—equally shared and maintained by all; 4) Resident management—everyone is expected to contribute, whether by making meals or maintaining the landscape; 5) Non-hierarchical structure and decision-making—there is no leader and everything must be done with consensus; and 6) No shared community economy—it is not to become a business or source of income. Within those six areas each cohousing community—or “coho” as it is commonly referred to by its members—has some flexibility in how they are administered. >>

WINNING HEARTS AND MINDS

Sir Thomas More first brought the concept to mainstream consciousness with his 1516 book he called Utopia

YOU SAY YOU WANT A REVOLUTION Bodil Graae wrote a newspaper column with the title “Children Should Have One Hundred Parents”

The first person we encountered at Tierra Nueva was Maren Brajkovich, a thirty-something mother of two, who moved in a year before her first child was born in order to “have a community around her” during this period of her life. She was first exposed to the concept when she was living in Fresno. During that time her husband, Michael, was teaching at a community college where he took on a class that explored utopian societies. A quick search online for modern-day utopias continued to produce hyperlinks to various cohousing communities. He was then surprised to learn that there was a nascent group in Fresno in the beginning stages of building a cohousing community there with a local presentation happening that week. Michael convinced his wife to come along to keep him company while he did his research. As she sat in the back row reading a book she had brought with her to pass the time, Maren, a wedding photographer, found herself tuning in to what they were saying. By the time the meeting was over she was asking questions. “I thought to myself, ‘Wow, this sounds like a great idea! Why aren’t people doing this? I want to see one.’” So that weekend, the couple hopped in the car for a trip to Oceano to take a look at Tierra Nueva—that same day they made the decision to buy. It was an uncharacteristically spontaneous move for the pair, who share that big-ticket purchases for them are usually agonizingly slow and painstakingly analyzed before any commitments are made.

But, it is that sort of gut-level desire to live in a cohousing community that brings together certain types of people, and everyone who commented for this story indicated that “a strong community” was at the top of their list. And, by all appearances, a strong community is thriving in the former avocado orchard adjacent to Rutiz Farms where ten or so kids of varying ages engage harmoniously on the playground equipment in the park at the center of the complex. A smattering of neighbors ranging in age from 35 to 75 stand nearby visiting with one another while keeping a watchful eye on the children. If one did not know better, it would appear to be some type of family reunion from the easy way that everyone interacts.

>>

[1. remnants of the commercial avocado orchard can be found throughout the property 2. resident housing utilizes passive solar heating 3. the children’s play structure acts as a centralized meeting place ]

1

1

[1. community members 2. walking paths criss-cross the five-acre property as no roads exist within the perimeter ] One of the benefits and drawbacks of cohousing—depending on whom you ask—is that there is no screening process. Anyone who wants to live in the complex and has the money to buy a unit is welcome to do so. In reality, cohousing communities are really just supercharged homeowner associations (HOA), which are bound by the same Fair Housing Act that all HOA’s must follow. This has created a couple of challenges at Tierra Nueva: first, there is a lack of ethnic diversity that members practically trip over themselves to apologize for; and, second, it has allowed a few people to enter who “do not participate.” One of the more pragmatic residents at Tierra Nueva reasons that the Fair Housing Act helps “keep us from going off the deep end by forcing us to deal with others who aren’t always of the same mindset.”

Despite the frequent socializing—Tierra Nueva residents sit down to dinner twice a week in their community room—the experience can lead to an island fever-like feeling. Caity McCardell, who produces radio podcasts, provides a very honest look at coho living. In the community room where a long-dead Christmas tree lingers in the corner stripped of its decorations, but waiting for someone to dispose of it, McCardell intimates that she and her husband and their young daughters had once considered moving to San Luis Obispo. “Cohousing is an isolating experience, and not having to drive anywhere is better for the planet and is appealing to me.” Neighbors who do drive “off-campus,” as McCardell describes it, usually ask her if there is anything they can pick up on her grocery list while they are out. Aside from missing many of the serendipitous encounters that happen all day long as neighbors and friends catch up with each other at grocery stores and restaurants and boutiques, McCardell wishes that there were at least a coffee shop nearby. “If only Peet’s or Starbucks would come to Oceano, it would make such a big difference.” housing vibe to it. All of the buildings, in that they look very similar to one another, have a vaguely institutional feel to them. The combination of duplexes and single-family homes were all built in the late 90’s, and they all sport the same terra cotta colored stucco siding along with white rimmed vinyl dual-pane windows. Their interiors are small with very limited closet and storage space and no garages. This design is employed for a couple of important reasons, as one resident pointed out, “We want to discourage personal stuff and encourage everyone to get outside.” Despite the neat and tidy homes, the focus for most of the residents falls to the common areas. The avocado trees that dot the property—remnants from its days as a commercial orchard—serve as a nice compliment to the abundance of bushes and flowers that line just about every square inch of available soil. The noticeable lack of streets—the hallmark of suburban America as kids stop whatever game they are playing to yell out “car!”—is refreshingly absent. Parking is limited and automobile access is available only on portions of the perimeter.

Despite the high-minded ideals of utopian societies, visitors to Tierra Nueva will be struck by the ordinariness of it all. Brajkovich shares that people unfamiliar with cohousing see it “as some sort of cult,” but asserts that they “are not weird, running around naked and smoking weed together.” Rather, she explains, it is a lot of hard work and everyone is not always in agreement—unanimous consent is required to create or change any rules—and sometimes people do not pull their own weight. Yet, despite the drawbacks, she claims that she would not want to live any other way. “People call it a village, and we know everyone. My daughter knew everyone’s name by the time she was two, including all the cats and dogs, which is cool, you know?” SLO LIFE