A detail of the medieval silver-gilt German chalice

On the cover:

A Medieval Silver-Gilt German Chalice

Probably Freiburg im Breisgau, c. 1350

Height: 6 1/4"; Weight: 7 oz. 5 dwt.

A chalice of similar form, with a knop flanked by apparently identical diestruck bands of roundels enclosing quatrefoils within beaded borders, and thought to have been made at Freiburg about 1350, is in the treasury at Freiburg Cathedral; see Johann Michael Fritz, Goldschmiedekunst der Gotik in Metteleuropa, 1982, p. 213, pl. 210.

It may seem odd that your neighborhood English- and American-silver dealer should offer a piece of German

Gothic silver, but it comes to us from the collection of one of the great dealers of the twentieth century, Hugh Jessop, whose wonderful things we have been selling for the last few years. The vast majority was English, but this and some other continental treasures were included, and in light of the near-impossibility of finding English hollowware of this period we are invoking the old Crosby, Stills and Nash line: if you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with. You will, in the words of Jimi Hendrix, know what I’m talking about if you take Bob Seger’s advice and turn the page: the earliest English piece we have is a spoon made about 170 years later.

S. J. Shrubsole

26 East 81st Street

New York, NY 10028

Tel: (212) 753-8920

E-mail: inquiries@shrubsole.com

www.shrubsole.com

Regular Hours: Monday to Friday, 10:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m.

Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

Summer Hours: (Memorial Day to Labor Day) Monday to Friday, and most Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

© Copyright 2025 S. J. Shrubsole, Corp. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Edited by James McConnaughy and Tim Martin, with contributions by Ben Miller Designed by mindovertools.com

Printed by GHP

Photography by Steven Tucker

I keep a cream skimmer by the great Huguenot silversmith Ayme Videau in a cabinet near my desk. It reminds me of the days my stepfather and I would travel to Grosvenor House and Olympia in June, do the Winter Show in January and tefaf in March, view the big New York and London auctions in April and October, and skim off what he loved to call “la crème de la crème.” I keep it, but its relevance as an analogy has faded — almost as much as its relevance as a kitchen utensil! These days I liken my job to those 1980s video games — Millipede, etc. — where things come raining down in a constant barrage in hundreds of places all at once and you scramble back and forth trying to catch the good and dodge the bad.

Last week I found a tankard in a country auction — one minute and thirty-four seconds before the hammer was to fall. Catalogued as English, it was in fact American, and pretty rare. I bought it (sight unseen which I try never to do) and enjoyed a couple of days of self-satisfaction before it arrived in the mail. It had been described as being in “overall excellent condition,” but not mentioned or shown in the photos was a sizable triangular patch to the front. It had been despouted — just about the worst repair a tankard can have. After a cordial conversation with an honorable auctioneer who had not been aware of the issue, I got my money back, and my humility. In the cream-skimming days, pre-internet, I would never have known that tankard existed; it would not have risen to the top. Sometimes I miss the staid, quiet regularity of those days, but mostly I don’t. Despite the pratfalls, the never-ending treasure hunt is a lot of fun, and as long as the delight in being able to offer great things large and small continues unabated, I’ll align myself with Harry Hotspur and say, “fie upon this quiet life, I want work.”

— Tim Martin

An Elizabeth I Seal-Top Spoon

London, 1596; Maker’s Mark: a cypher Length: 6 1/2 "; Weight: 1 oz. 12 dwt.

Provenance: J.H. Bourdon-Smith Ltd., London, 1991

The Honourable Justice John Batt, Melbourne, Australia

A Provincial Maiden-Head Spoon

c. 1520; Maker’s Mark: S in reverse Length: 6 1/4"; Weight: 1 oz. 1 dwt.

The marks on this piece are illustrated in G. E. P. How, Silver Spoons and PreElizabethan Hall-Marks on English Plate, 1953, vol. 3, Chapter VI, plate 2 of Section IX. How suggests a date of 1510–30.

Provenance: The Chichester Collection

A Henry VIII Apostle Spoon, St. Andrew

London, 1542; Maker’s Mark: a feather Length: 6 7/8"; Weight: 1 oz. 17 dwt.

An Elizabeth I Silver-Gilt Mounted Tigerware Jug

London, 1559; Maker’s Mark: SK

Height: 8 1/4 "

An Elizabethan Tigerware jug. Ay, madam, it is common: the commonest surviving Elizabethan form aside from spoons. But the vast majority of these have been altered or damaged, and fine examples of the form — as in this case, perfectly preserved — are pretty rare.

A Silver-Gilt Mounted

Wanli Chinese Ewer

The mounts probably English, possibly Dutch.

c. 1620

Height: 8 1/4 "

A similar ewer with naturalistic root forms around the spout is in the Franks Bequest at the British Museum. It is very difficult to be sure of the origins of the mounts, and the only reason we say probably English is that the ewer was bought in England nearly 100 years ago.

Literature: Edward Wenham, “Silver Mounted Porcelain”, Connoisseur, vol. 97, no. IX, April 1936, pp. 185–194

Timothy Schroder, Renaissance and Baroque Silver, Mounted Porcelain and Ruby Glass from the Zilkha Collection, London, 2012, cat. no. 55, pp. 232–233

Provenance: Crichton Brothers, London, c. 1936

Galerie Kugel, Paris, 2002

A James I Silver-Gilt Steeple Cup with Later Cover

London, 1606 by Anthony Bennett, the cover 1879 by Robert Harper

Height: 22 1/2"; Weight: 43 oz. 3 dwt. Norman Penzer listed 148 known steeple cups in the 1940s. Ninety percent of them were in churches, municipal corporations, Oxford or Cambridge colleges, or, because the Tsars received them as diplomatic gifts, the Kremlin. Of the sixteen in the Kremlin, only four have their covers, so we don’t feel too bad about this one, which lost its cover, but was taken by its owner to a very good silversmith to have it reproduced. Like Notre Dame, or Saint-Malo, we should just be glad it is there.

At right: In illustration of the delightful variety of form and decoration on Jacobean steeple cups, here are a number of exceptional (if not well-preserved) examples from the great collection of English silver at the Kremlin Armory.

A Charles I Wine Taster

London, 1647; Maker’s Mark: SA Length: 5 1/8"; Weight: 2 oz.

A Charles II Wine Taster

London, 1661; Maker’s Mark: HB Length: 3 7/8"; Weight: 1 oz. 1 dwt.

A Charles I Sweetmeat Dish

London, 1634 by William Maddox Length: 8 1/8"; Weight: 4 oz.

Provenance: Sotheby’s, New York, 22 October 1993, lot 32, property of Richard George Meech

(Clockwise from top left:)

A Commonwealth Wine Cup

London, 1657; Maker’s Mark: TC (possibly for Tobias Coleman)

Height: 3 1/8"; Weight: 2 oz. 11 dwt.

A Rare Provincial Charles II Wine Cup

Warminster, c. 1665 by Thomas Cory Height: 3 3/8 "; Weight: 1 oz. 13 dwt.

Warminster is a market town in western Wiltshire. Cory moved there around 1662, having trained in London and been made free of the Goldsmiths’ Company in 1655.

A Charles II Beaker

London, 1665; Maker’s Mark: RM

Height: 3 5/8"; Weight: 4 oz. 8 dwt.

An absolute gem of a beaker.

Literature: Robin Butler, The Albert Collection: Five Hundred Years of British and European Silver, 2004, p. 110

An Unusual Charles II Porringer

London, 1672 by Thomas Allen Height: 3"; Weight: 5 oz. 14 dwt.

This piece is in excellent condition, with no repairs or splits, and so has a lovely color and patination with very clear marks. The grape decoration is unusual.

A Charles II Bleeding Bowl

London, 1674 by Edward Gladwin Length: 5 3/8"; Weight: 8 oz. 6 dwt.

The best bleeding bowl, or, porringer, you are ever going to see.

Provenance: How of Edinburgh, London, 1990

Fred & Anne Vogel, Milwaukee

A Charles II Trencher Plate

London, 1673 by Martin Gale

Diameter: 10 5/8"; Weight: 16 oz.

Literature: The Burlington Magazine, Review, “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions”; The Grosvenor House

Antiques Fair, vol. 118, no. 879, June 1976, p. 447, fig. 144

Provenance: Sir Peter Pindar, 1st Bt. of Edenshaw (d.1693), co. Chester Thomas Lumley Ltd., London, 1976

(Clockwise from top left:)

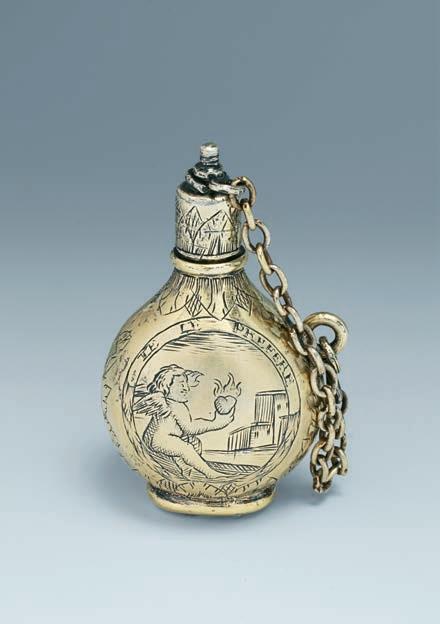

A Small Charles II Silver-Gilt Perfume Flask

c. 1680

Height: 1 3/4"; Weight: 10 dwt.

Finely engraved with Cupid holding a flaming heart, and the words je te prefere. A tiny and delightful object,

modelled as the larger pilgrim bottles popular at the time.

A William III Tot Cup

London, 1697 by Ferdinando Hughes

Height: 1 7/8"; Weight: 2 oz.

Another small piece of perfection.

A William & Mary Silver-Gilt Trefid Spoon

London, 1689; Maker’s Mark: IH

Length: 8"; Weight: 2 oz. 18 dwt.

A great spoon, an ounce or so heavier than even very good trefids of the period.

A Very Rare Charles II

Napier’s Bones Arithmetical

Calculation Table

c. 1680

Length: 2 3/4"; Weight: 2 oz. 16 dwt.

Engraved with the arms of Oliver St. John, 2nd Earl of Bolingbroke, and his wife Francis Cavendish.

A Napier’s Bones, or Napier’s Fingers, is an arithmetical tool. Its simplest use is to reduce multiplication to addition,

and division to subtraction, and its more complicated uses are way, way too complicated for me to even copy out from Wikipedia. It was created following the 1614 publication of Mirifici Logarithmorum Canonis Descriptio by the Scottish mathematician, physicist, and astronomer John Napier (1550–1617), 8th Laird of Merchiston. This is the

only set we have ever seen in silver, and it is one of the earliest sets to survive in any material.

Provenance: Oliver St. John, 2nd Earl of Bolingbroke (before 1634–1688), by descent in the Cavendish and Montagu families to the Earls of Home at The Hirsel, Berwickshire

A James II Provincial Porringer

Norwich, 1688 by Elizabeth Haselwood

Height: 2 7/8"; Weight: 5 oz. 2 dwt.

A handsome caudle cup, or porringer, by the early Norwich silversmith Elizabeth Haselwood.

A William & Mary Chinoiserie Porringer

London, 1690 by John Duck

Height: 3 1/2"; Weight: 10 oz. 10 dwt.

Provenance: Sotheby’s, London, 9 October 1969, lot 236

The Ortiz-Patiño Collection, English 17th-Century Chinoiserie Silver; Sotheby’s, New York, 21 May 1992, lot 145

A James II Snuffer & Stand

London, 1688; Maker’s Mark: BB Height: 7 1/2"; Weight: 13 oz. 7 dwt.

This appears to be one of two known examples of this date and maker. Together they are the earliest fully hallmarked snuffers and stands to survive in English silver. The other example, which we know only from a photo, appears to have had some damage and alterations, and must be classified under that Pavlov’s bell of a category: “present whereabouts unknown.”

A William III Cup & Cover

London, 1702 by

David Willaume

Height: 8"; Weight: 33 oz. 2 dwt. Heavy, beautifully patinated, with fine cut-card work and gadrooning, and in excellent condition.

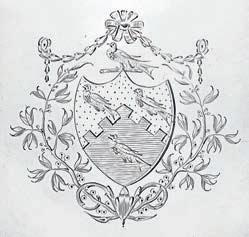

A Queen Anne Cup & Cover

London, 1702 by Pierre Platel

Height: 9 1/2"; Weight: 46 oz. 17 dwt.

The arms are those of Pole or Poole with a baronet’s canton. They could be for Sir James Poole (c. 1640 – c. 1710) who was created Baronet Poole in 1677, or for Sir John Pole (1649–1708),

3rd Baronet Pole of Shute House.

This is a gorgeous model. It appears to have been unique to Platel. A pair, nearly identical, engraved with the Gorges coat of arms, was sold some years ago from the Gilbert Collection.

A Queen Anne Tankard

London, 1705 by David Willaume

Height: 7"; Weight: 28 oz. 10 dwt.

Tankards by Huguenot silversmiths are rare. There are three known by Lamerie and precious few by Harache, Liger, Archambo, Courtauld, Feline, Videau, etc. etc.

This is a nice simple form, with great marks and a fine contemporary cypher on the front.

Provenance: Christie’s, London, 3 March 1976, lot 110

A Queen Anne Teapot

London, 1707 by Benjamin Pyne

Length: 7 7/8"; Weight: 21 oz. 19 dwt.

Exhibitions: The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, 1953, no. 1, p. 3

Henry Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California,

Jan.–Feb. 1956, no. 1, p. 1, ill. p. 2

The Dayton Art Institute, Oct. 1958, no. 4

The Portland Museum of Art, Feb. –March, 1954

Provenance: The Lipton Tea Company, Hoboken, New Jersey

A Pair of Queen Anne Tea Caddies

London, 1704 by Benjamin Pyne

Height: 4 3/8"; Weight: 15 oz. 9 dwt.

One of the earliest pairs of tea caddies known in English silver, these have a bold, simple form and utterly gorgeous marks — the truth of which adjectival

abundance makes up in my mind for the arms being erased, probably two hundred years ago, and replaced with the crest that’s there now.

Provenance: Sotheby’s, London, 8 June 1995, lot 161. This was an exceptional sale of things from the family of Lord Chancellor King.

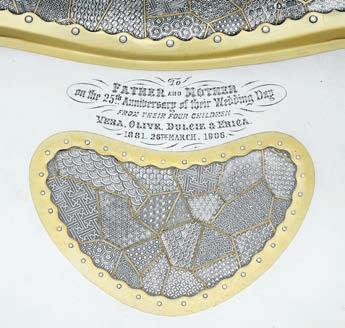

An Unusually Large Pair of George I Tea Caddies

London, 1716 by John Farnell

Height: 5 5/8"; Weight: 21 oz. 19 dwt.

The arms are those of Impey, of Hammersmith, London.

The inscription on one reads holds 1/3 of a pound; the other, partly legible, This tea Caddie was given by Mrs. Fuller to her daughter Eliza wife of WM. Churton, & by her was

transmitted to her daughter Eliza wife of H.P. Churton m. 1852, who in turn left it to her son Henry Churton AD 1878.

Provenance: The Impey family, Hammersmith, presumably given to Mrs. Fuller, by bequest to her daughter, Eliza Fuller (1784–1852), wife of William M. Churton (1770–1851), a hosier of 91 Oxford Street and Sutton Court Lodge, Chiswick, to their daughter,

Eliza Fuller (1808–1878), wife of Henry Parsons Churton (1804–1890), of Hammersmith, to their son,

The Reverend Henry Churton (d.1934),

S.J. Shrubsole, New York

A New England Collection (Robert S. Pirie); Christie’s, New York, 16 April 1999

The Bayreuth Collection, Belgium, sold Christie’s, London, 7 July 2023, lot 176

A George I Silver-Gilt Casket

London, 1725 by John Edwards

Length: 10 3/8"; Weight: 69 oz. 5 dwt. The arms are those of Nightingale impaling Shirley for Joseph Gascoigne Nightingale (1695–1752) and his wife Elizabeth (1704–1731), the eldest daughter of Washington Shirley, 2nd Earl Ferrers (1677–1729), whom he married in 1725.

People sometimes tell me silver is “out of fashion.” But when I ride my bike up Madison Avenue, or wander Bond Street or the Rue du Faubourg SaintHonore, I see the names of some pretty serious silver collectors above the shops. Yves Saint-Laurent was the most notable example in recent years, but this casket came from the silver-heavy collection of Hubert de Givenchy.

A George I Teapot

London, 1725 by Samuel Wastell Height: 4 7/8"; Weight: 13 oz. 15 dwt.

The later eighteenth-century arms are those of Hudson and are unusual in that they were granted to a woman, Elizabeth Hudson, in 1766.

Exhibitions: The Virginia Museum of

Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia, 1953, no. 2, p. 4

Henry Huntington Library and Art Gallery, San Marino, California, Jan. – Feb. 1956, no. 6, p. 3

The Dayton Art Institute, Oct. 1958, no. 8

The Portland Museum of Art, Feb.–March, 1954, no. 6

Provenance: The Lipton Tea Company, Hoboken, New Jersey

A Set of Four George I Candlesticks

London, 1725 by Thomas Farren Height: 6 3/8"; Weight: 51 oz. 4 dwt.

(Clockwise from top:)

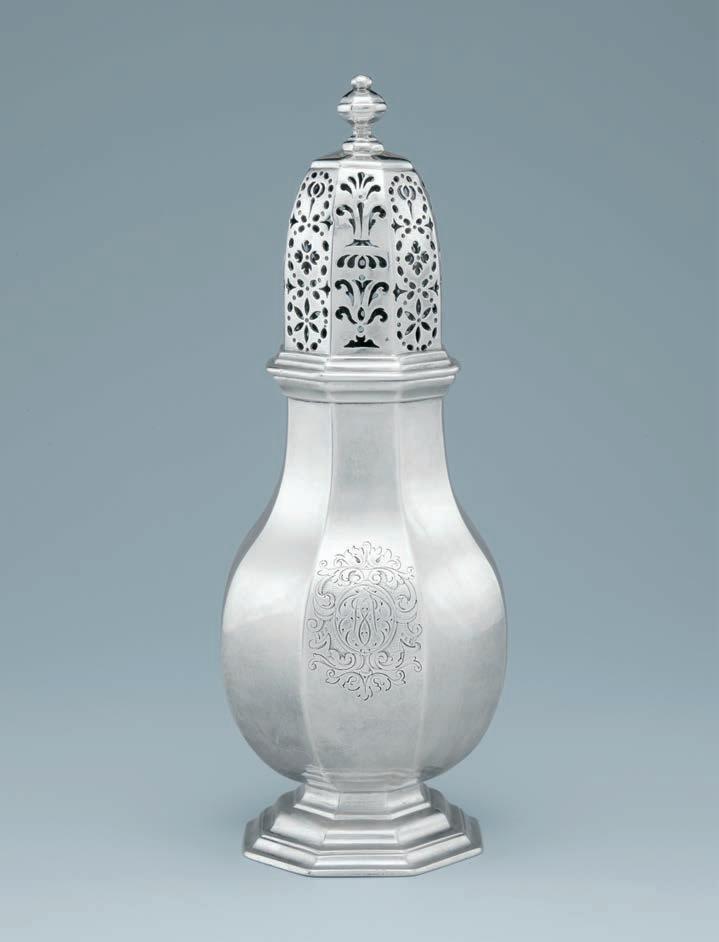

A Queen Anne Octagonal Caster

London, 1713 by Robert Cooper

Height: 8 1/4 "; Weight: 13 oz. 8 dwt.

A fine and heavy caster from the great collection of Hugh Jessop.

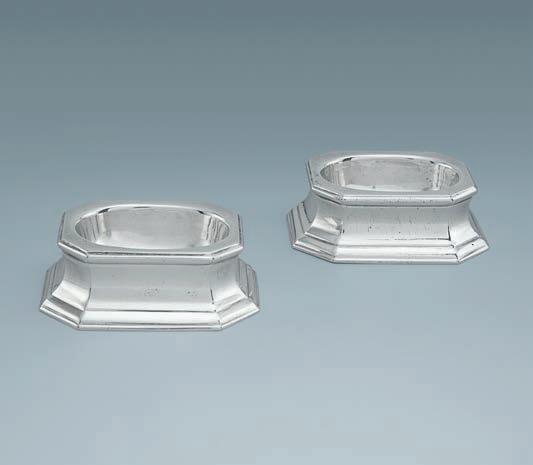

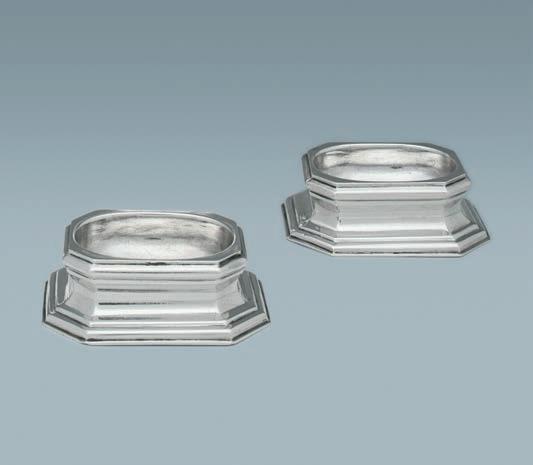

A Pair of George II Salts

London, 1727 by James Stone

Length: 3"; Weight: 3 oz. 13 dwt.

A Pair of George I Salts

London, 1726 by James Gould

Length: 3"; Weight: 7 oz. 14 dwt.

Of an extremely rare cast type, as opposed to the usual examples wrought from sheet. They are more than twice as heavy as the very fine pair to their right.

A George I Salver

London, 1726 by John Tuite

Length: 13 1/8 "; Weight: 52 oz. 6 dwt.

The arms and initials are those of Standish impaling Howard for Ralph Standish (1670–1755) of Standish, co. Lancaster, and his wife Lady Phillippa

Howard (1678 –1731), the youngest daughter of the 6th Duke of Norfolk.

Provenance: S.J. Shrubsole, New York, 1980

Anne Bass, New York

A George II Kettle & Stand

London, 1734 by Edward Vincent

Height: 13 1/2 "; Weight: 81 oz.

The arms, which include three swimming turbots, are those of Turbott impaling Babington for Richard Turbott, Esq. of Doncaster (c. 1689–1758).

He married first, Mary-Ann Revel,

daughter and coheir of John Revell, Esq. of Ogston, co. Derby, and secondly the heiress Frances Babington.

Provenance: Thomas Lumley, Works of Art, Ltd.

George S. Heyer, Jr., Austin, Texas

A

George II Cup & Cover

London, 1731 by Simon Pantin

Height: 13 1/4 "; Weight: 102 oz.

The arms are those of Jolliffe with Mitchell in pretence for John Jolliffe of the Inner Temple, London, who was

married to his first wife, Catherine Mitchell, on 30 March 1731 at St. Christopher Le Stocks, London. She, who was the daughter and heir of Robert Mitchell (d. 1739) of Petersfield, died within three months of their marriage. The later Baron’s coronet is most probably for Sir William Jolliffe, 1st Baron Hylton, a great-grandson of John Jolliffe.

London, 1741 by Jonathan

Height: 4 1/2"; Weight: 36 oz. 5 dwt. Wonderful weight and perfect condition.

A Rare Set of Twelve George II Gold Teaspoons & Sugar Nips

London, c. 1740 by John Wirgman

Length of Teaspoons: 4 1/4";

Weight: 6 oz. 12 dwt.

Only three sets of Georgian gold teaspoons are known, and this is the only set of twelve. The others are:

• A set of six teaspoons and a sugar nipper with shell-shaped bowls, c. 1750 by FH; in the Gilbert Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

• A set of six c. 1730, unmarked, with a pair of sugar tongs and a straining spoon, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Gilbert Collection catalog states (p. 295): “English gold plate other than snuffboxes and freedom boxes is very rare: a list published [in 1951] of all items then known from the period 1507–1830…amounted to only about eighty objects.”

Provenance: Herbert Augustus Salwey (1848–1939) of Runnymede Park, Surrey

Christie’s, London, 19 April 1936, lot 190

Michael Noble, Christie’s, London, 13 December 1967, lot 41

Jaime Ortiz-Patino, Christie’s, London, 2 June 2009, lot 173

A George II Teapot

London, 1746 by Paul de Lamerie

Height: 7 5/8"; Weight: 14 oz. 18 dwt. Engraved with an Earl’s coronet above the mirror cypher ac for Charles Bruce, 3rd Earl of Ailesbury and 4th Earl of Elgin (1682–1747). His third wife was Lady Caroline Campbell, daughter of John Campbell, 4th Duke of Argyll.

Provenance: by descent through the Dukes of Argyll to Niall Diarmid Campbell, 10th Duke of Argyll (1872–1949)

The Trustees of His Grace the Duke of Argyll; Christie’s, London, 9 July 1941, lot 36

S.J. Phillips Ltd., London

Anne H. Bass

A Pair of George II Candelabra

London, 1751/2

by Charles Frederick Kandler

Height: 14 1/2"; Weight: 116 oz. 3 dwt.

The crest is that of Pitt, presumably for Thomas Pitt (1737–1793) who was created Baron Camelford in 1784, or for his son Thomas, second Baron, who

died in 1804 at which point the Barony became extinct. Both were important members of the English political and intellectual life in the second half of the eighteenth century.

A similar pair of candelabra by Francis Butty and Nicholas Dumee, 1757,

with similar flower finials are in the possession of the National Trust and Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire.

Literature: Arthur Grimwade, Rococo Silver: 1727–1765, 1974, p. 56, illustrated pl. 78

Provenance: Partridge, London, 1991

A Pair of George III Candlesticks

London, 1774 by Peter Desvignes

Height: 11"; Weight: 54 oz. 4 dwt.

A Set of Four George III Salts (Opposite page)

London, 1773 by Peter Desvignes

Length: 4 5/8"; Weight: 21 oz. 12 dwt.

Like the candlesticks above, these are a product of the intriguing goldsmith Peter Desvignes, nearly all of whose work is in this very fine French taste.

A Set of Six George III Wine Goblets

(At left and below)

London, 1769 by Walter Brind Height: 5 1/4"; Weight: 40 oz.

The coronet, crest, and motto are those of Henry Paget, Marquess of Anglesey, a hero of the Battle of Waterloo. On having his leg shot off by cannon fire, he said to Wellington “by God Sir, I have lost my leg!” To which Wellington responded, “By God Sir, so you have.”

Paget (pictured at left) was the Earl of Uxbridge at the time of the battle, and he was raised to Marquess the next month. Full details along with many other stoical and apocryphal quips can be found on a Wikipedia page entitled “Lord Uxbridge’s Leg”.

An

Early American Cann

Boston, c. 1740 by George Hanners

Height: 5"; Weight: 10 oz. 16 dwt.

Literature: Patricia Kane, Colonial Massachusetts Silversmiths & Jewelers, 1998, p. 527 and p. 520

A George II Salver for a Virginia Family

London, 1749 by John Swift

Diameter: 9 3/4"; Weight: 15 oz. 14 dwt.

The arms are those of Chapman impaling Pearson for the Chapman family of Summer Hill Plantation, Arlington County, Virginia.

This piece is documented by both a rare nineteenth-century family tintype of the salver and a picture of the Chapman Family silver in The History of the Alexander and Chapman Family in Virginia, by Sigismunda Mary Frances Chapman, 1946.

Provenance: Charles C. Williams (1925–1996)

Helen C. Calvert, 1990

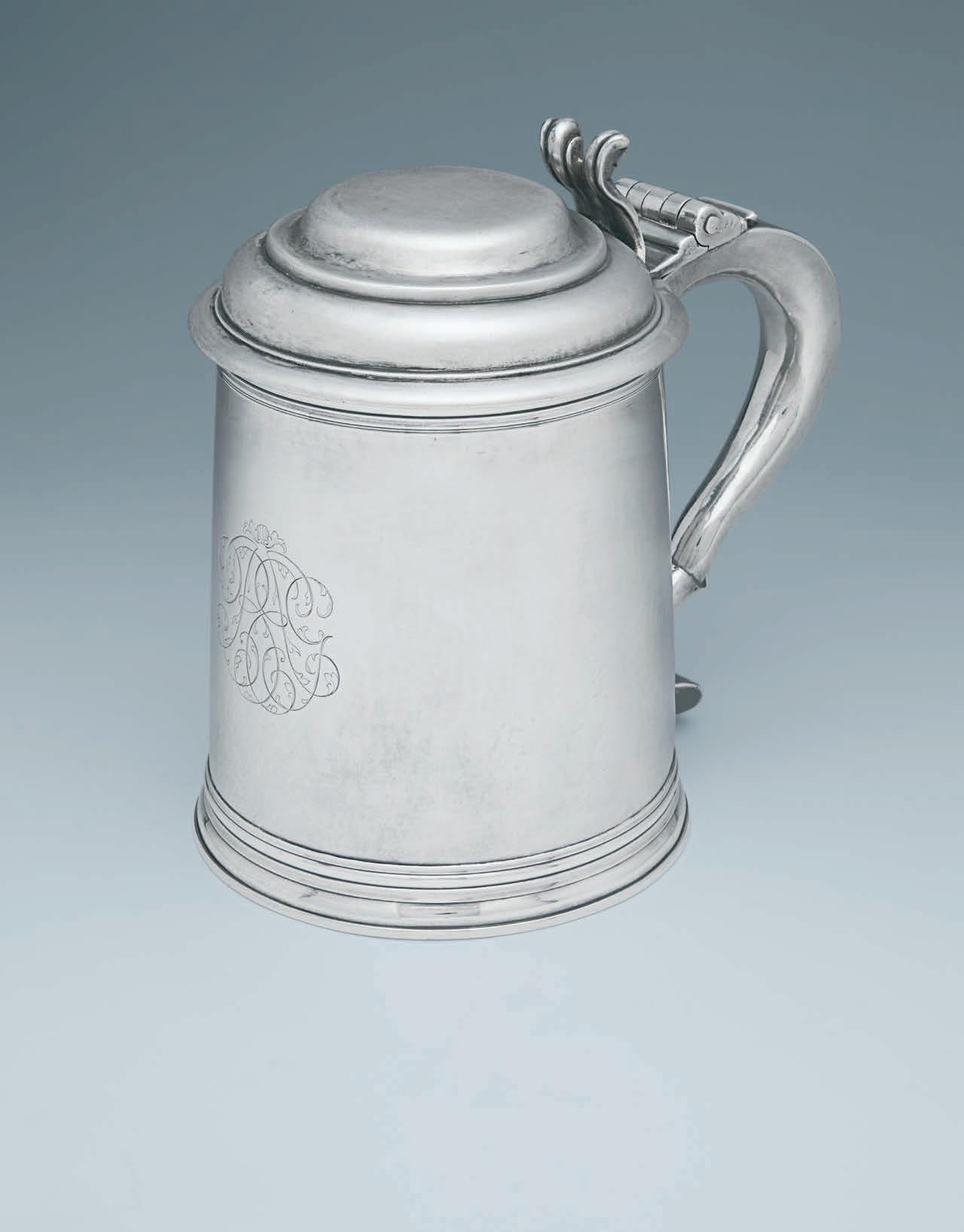

An Early American Tankard

New York, c. 1740 by John Brevoort

Height: 71/2"; Weight: 40 oz.

Very few of these Dutch New York tankards make it to the 40 ounce line, the official number for “awesome” status. Chance or nature’s changing course will come for it, but not yet.

(Clockwise from top left:)

An Early American Caster

Boston, c. 1760 by Zachariah Brigden Height: 5 3/4"; Weight: 3 oz. 12 dwt.

Provenance: Jonathan Trace, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 2015

An Early American Caster

Boston, c. 1760 by Zachariah Brigden Height: 5 3/8 "; Weight: 2 oz. 17 dwt.

An Early American Caster

Boston, c. 1760 by Samuel Minott Height: 5 3/4"; Weight: 4 oz. 2 dwt.

An Early American Caster

Boston, c. 1760 by John Coburn Height: 5 3/4"; Weight: 4 oz.

A Pair of Early American Canns

New York, c. 1785 by Daniel Van Voorhis Height: 5"; Weight: 14 oz. 8 dwt.

A fine pair of canns by “the Paul Revere of New York”. That’s a joke, but Van Voorhis was a patriot. He fought in the Revolutionary War, and at the Battle of Princeton he was promoted to the command of his company by General Washington himself.

The initials on these canns can be assigned to a member of the Brinkerhoff family. One of them was purchased from a family descendant, and we reunited it with the other, which we bought in the trade.

An Early American Sauce Boat

New York, c. 1835 by Baldwin Gardiner Length: 9 1/8"; Weight: 20 oz. 6 dwt.

A similar example is in the Metropolitan Museum, accession number 2019.439.2.

(Clockwise from top left:)

An Early American Porringer

Newport, c. 1730 by Samuel Vernon Length: 7 1/2"; Weight: 7 oz. 16 dwt.

An Early American Porringer

New York, c. 1760 by Samuel Tingley Length: 7"; Weight: 6 oz. 13 dwt.

This handle design was used only in New York. It was particularly popular with Myer Myers, who seems to have worked very closely with Tingley.

An Early American Porringer

Boston, c. 1720 by John Edwards Length: 8"; Weight: 10 oz. 12 dwt.

A very early and beautiful porringer with a rare style of handle. The engraved initials and date (1745) are slightly later. It is one of the heaviest porringers we have had.

Literature: Patricia Kane, Colonial Massachusetts Silversmiths and Jewelers, 1998, p. 416

Kathryn C. Buhler, “John Edwards, Goldsmith, and his Progeny”, The Magazine Antiques, vol. LIX, no. 4, April 1951, pp. 289–290, fig. 5

Provenance: S. Franklin, by 1745

Mrs. Robert C. Terry, by 1951

An Early American Porringer

Boston, c. 1720 by George Hanners Length: 8"; Weight: 8 oz. 6 dwt.

Provenance: Huidekoper-Romaine families of Baltimore, Philadelphia and Cape Cod

Jonathan Trace, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1996

Sotheby’s, New York, The Collection of Roy and Ruth Nutt: Highly Important American Silver, 24 January 2015, lot 703

An

Early American Beer Jug

Boston, c. 1795 by Robert Evans

Height: 7 1/2"; Weight: 20 oz. 19 dwt.

A so-called “Liverpool jug.” Many of the surviving examples of this form are by Revere, and one wonders whether his shop made them all, and sold some

in the trade. A few years ago we had one marked by Revere on the inside, and Moulton on the outside. Robert Evans is not a well-known silversmith. Ensko records that he married a Mary Peabody and that he died intestate.

An American Mixed-Metals Inkwell

(At far left, top)

New York, c. 1880 by Tiffany & Co. Height: 2 1/2"

An American Mixed-Metals Inkwell

(At far left, middle)

New York, c. 1880 by Tiffany & Co. Height: 2 3/4"

Provenance: The Jerome Rapoport Collection of American Aesthetic Silver

An American Parcel-Gilt Paper Knife

New York, c. 1880 by Tiffany & Co. Length: 7 1/2"; Weight: 3 oz. 3 dwt.

An American Parcel-Gilt & Enamel Pen Tray with Chamberstick

New York, c. 1885 by Tiffany & Co. Length: 9"; Weight: 9 oz.

Provenance: Christie’s, New York, 21 January 2000, lot 262

Aso Tavitian

Sotheby’s, January 2025

A Komai Pattern Parcel-Gilt Bachelor Tea Set

Birmingham, 1879 by Elkington, designed by Christopher Dresser

Length of Tray: 18 7/8 "

Weight: 75 oz. 11 dwt.

Consisting of a teapot, sugar bowl, milk jug, six matching teaspoons, sugar nips and a tray. The irregular geometric patterning clearly shows the influence of Japanese art on this important designer.

Literature: Stuart Durant, Christopher Dresser, London, 1993, (p. 89, similar design illustrated)

Widar Halén, Christopher Dresser, London, 1990, (p. 151, similar design illustrated)

Fine Art Society, The Aesthetic Movement and the Cult of Japan, October 1972, no. 234 (similar design exhibited)

On the back cover: An American Mixed-Metals Jug

New York, c. 1878 by Tiffany & Co.

Height: 8 7/8 "; Weight: 36 oz. 4 dwt.

Because it would be hard to imagine a better one, and because we’ve seen several examples all worn out, we know this is one of the finest of the relatively small number of jugs of this model known. We also feel that this model, with this program of decoration is, of all the jugs Tiffany made, their best. Evidence for the durability of this opinion can be found in the rapturous review of Tiffany’s stand at the Paris Exposition of 1878 by the poet, playwright, and essayist Emile Bergerat. Bergerat’s selections of about ten pieces to be reproduced in his article, in woodcut illustrations, include many of what are still considered the finest pieces Tiffany exhibited. One of them, unsurprisingly, was a jug of this exact model.