8 minute read

Mentions in Despatches

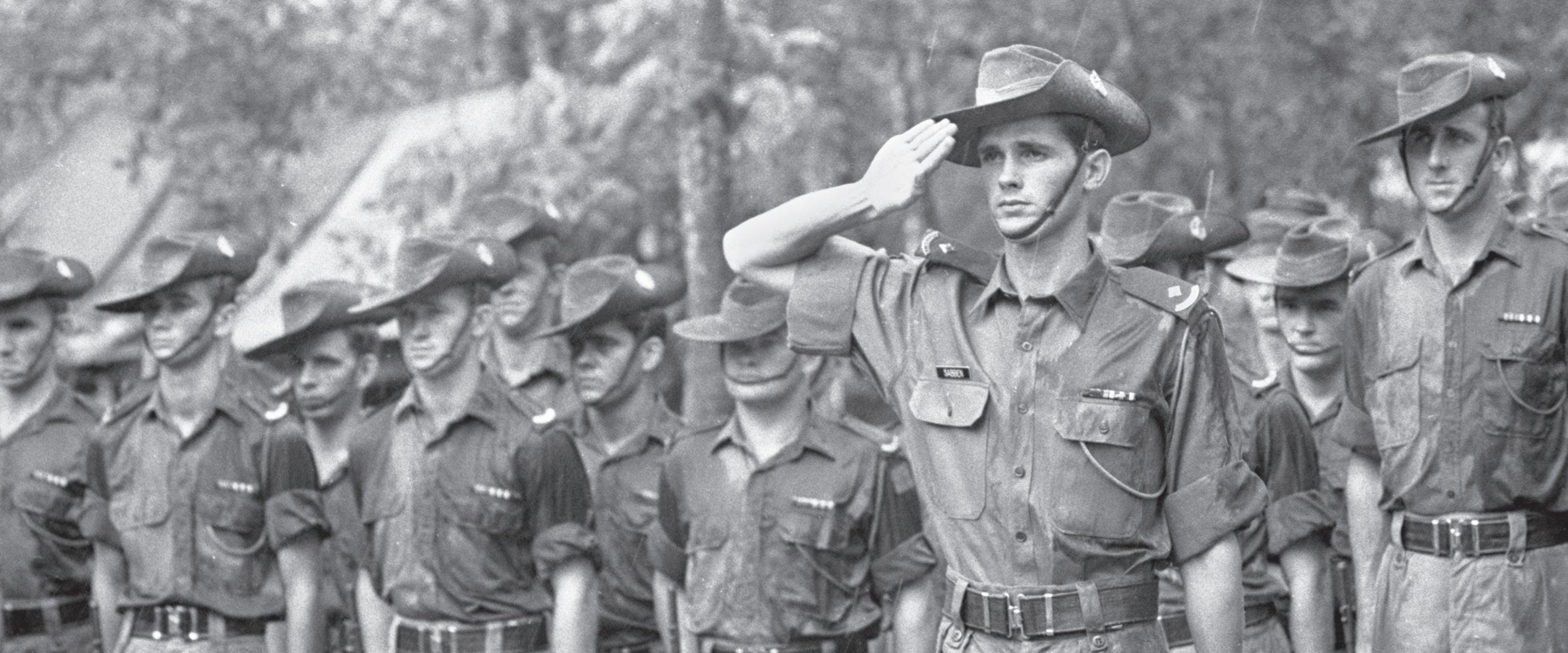

By Dave Sabben MG

We know about the politics that got us into and out of the ‘war’. We know about the big battles: Long Tan, Coral, Balmoral, Binh Ba. We know about the social issues: conscription, drugs, moratoriums, the uneasy returns home. And we know about the legacy: the trauma, the PTSD, the divorces, the suicides. But do we know what actually happened there? Do we know exactly what our soldiers did, day by day, week by week? Do we understand what they experienced? What they did? What they thought about what they did?

This book will take you into an average Infantry Platoon for a 12-month ‘Tour of Duty’ in the year the Task Force base was set up.

It will take you from the early days, in June 1966, when a bare rubber plantation was occupied in the middle of an enemy-controlled province, and a new operational base established.

Hundreds of soldiers endured getting six two-hour sleeps every three days for weeks on end. In between those sleeps, they patrolled with heavy kit in dust-dry or monsoon-wet (but always dangerous) conditions to clear the enemy from their own bases. And when not on patrol, they were digging pits, trenches, command posts and latrines. When not on patrol or digging, they were clearing the undergrowth and erecting barbed wire fences.

And when they did sleep, it was on groundsheets under plastic ‘hoochies’ without lights and always with a weapon within reach. Showers were rare but mildew was everywhere. Food was mostly out of ration cans. Feet were rarely out of boots.

It was only later, when the base was a little more secure, that tents and stretcher beds became available. Then the pace did slacken, but only slightly. One- and two-day patrols gave way to one- and two-week operations, as they cleared further out from the Nui Dat base.

Excerpts from the book Mentions in Despatches

Down a VC Tunnel

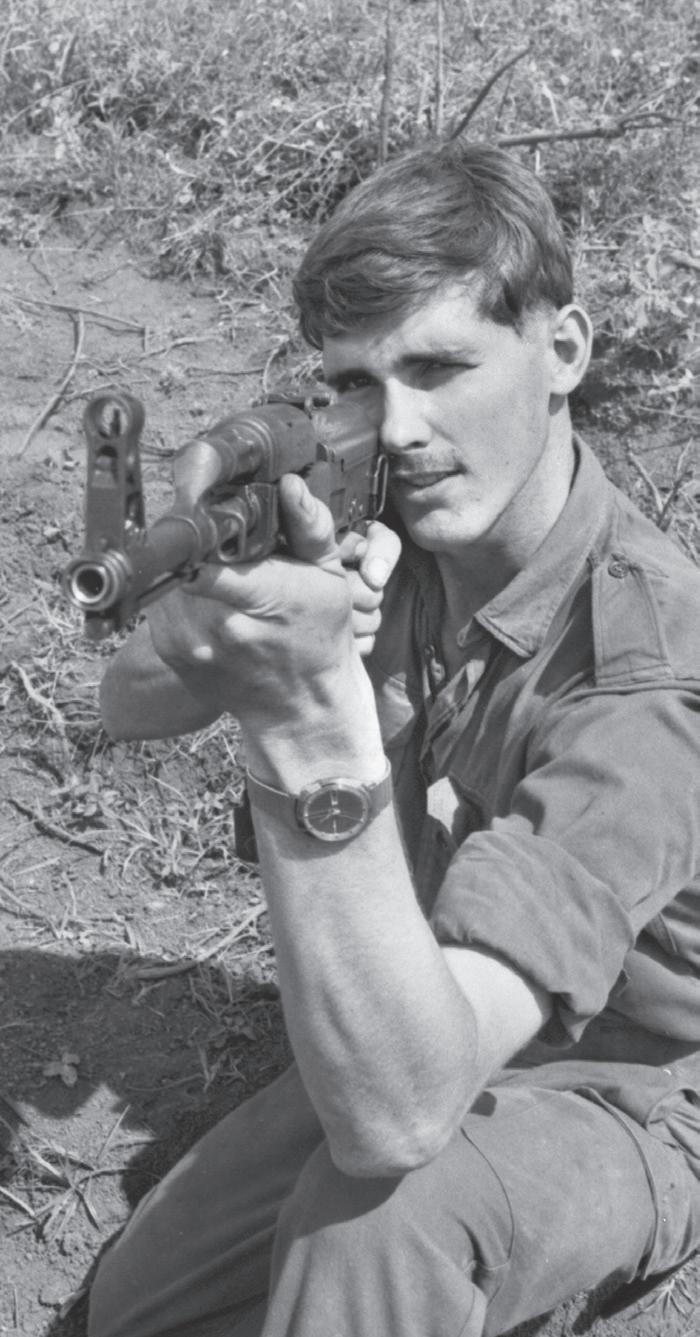

Approval has been given for me to go down the tunnel, and I admit to being nervous, despite the fact that it is once more cleared by the Sapper prior to the charges being placed.

The access pit isn’t inviting. It’s grasscovered, wet and muddy. The tunnel itself is about 2’ by 2’ at the entrance - a little smaller than a card table – and requires entry head first. I lie on the pit lip, and slide in.

The fetid smell hits with an almost solid shock. The floor is 2” of wet mud, and the walls are hung with spiderwebs and insects. I switch on the Sapper’s torch and prepare to go on.

In front of me, the tunnel proceeds at 2’ x 2’ for about 6’, then there’s a 6” step up in the floor and the walls slope inwards about 3” each, the roofline continuing uninterrupted. The tunnel divides at that point, a smaller passage to the right, the main one continuing ahead as far as the torch lights - about 20’.

I crawl to the first passage and look around. The side passage is too small for me to enter. It’s about 12” to 15” square. It goes a few feet along, and then turns right again. The sapper had said that it stops abruptly a few feet from that bend. I turn again to the main tunnel.

The walls and roof are cut dead square, apparently perfectly level and smooth. The floor is rough, where the Sapper has preceded me. I can no longer crawl. I have to hunch my shoulders, and even then, they are touching each side. With arms out in front of me, one holding the torch, I can inch forward on elbows, knees and toes. The stink of rot is blinding, bringing tears to my eyes. I feel the oppression of the walls.

15 yds along, and the torch picks out an irregularity in the wall. As I get level with it. I see it’s where the Sapper has dug away a bit of wall with a bayonet. I realise that I have no chance to get at mine in this position, even though it’s on the belt at my side right now.

The passage forms a ‘T’ up ahead, with a passage leading off to left and right. I go right, taking advantage of the corner to get my bayonet.

I go on, even though I’ve been told it’s a dead end. What I haven’t been told is that it reduces in size before it deadends. I find myself backing out of a tunnel that I can’t even hold my head up in.

The SLR bayonet is almost exactly 8” of blade and 4” of handle and hilt. I measure the tunnel, and it’s 16” square. A flicker of the torch tells me it’s time

to leave. I successfully negotiate the ‘T’ junction only by shaving a few inches off the corner and proceed left instead.

Two bends later, I feel a change in the air, and rounding another corner, I see light. Never a more welcome sight! I must have got used to the smell, because a whole new degree of evil smell assails me. The tunnel ends in the bunker, with a trap door (now open) to one side. In the bunker is a pile of overrotten fruit and other matter too foul to identify - that’s the new smell.

I’ve heard the expression ‘to gulp fresh air’ and taken it as a figure of speech. Now, as I gulp fresh air, I value its descriptive powers. I’m dirty all overnot just dirty, but DIRTY. Caked in muck. I don’t know how, but the Sappers don’t seem to get so dirty.

On Arrival at Saigon

The company files aboard the two buses look brand new on the outside, but inside, the seats are worn and split. No doubt countless passages by similar occupants, with their boots, bayonets, buckles and blunderbusses, have contributed to their early demise.

The windows are welded shut on the outsides and are covered with a thick wire mesh – against grenades being thrown through. The mesh forbids the windows being cleaned, except by hose-down, so the view is less than perfect.

Still, the shade is welcome, and since the trip will be short, we don’t reckon we’ll miss much.

We’re wrong. In only half a mile, we pass hangars, storehouses and rows of vehicles brimming full of all manner of equipment and materiel. There are a few gun emplacements housing anti-aircraft guns which can’t have been fired yet.

Beyond the few commercial jetliners are uncountable military aircraft of all shapes and sizes, from the giant Starlifters, which look like they’d take a wing-folded 707 in their hold, down to the single-engine ‘Birddog’ aircraft.

Up one arm of the runway are acres of Iroquois helicopters - the UH1b and UH1d models familiar to us as the ‘Huey’ choppers of our training flights and the occasional TV war news telecasts.

There are metal container boxes - camouflage painted this time - stacked two and three high around fuel and ammo dumps. Other dumps are dug in with earth revetments.

Across the runway is a line of Phantom jets, each in its own earthworks bay and covered with camouflage netting - more for shade than camouflage, I suppose.

Everywhere, service men scuttle to and fro’, each on his (no ‘her’ to be seen!) own vital mission. The 10-mph bus speed limit is never reached, as we slow or stop for every forklift, tractor, jeep and trooper. Some unseen priority system gives anything but a bus right-of-way.

The half mile seems to take forever. Hardly the Red Ball Express, but we’re so preoccupied with the logistics that we don’t really notice the time.

Dave Sabben MG volunteered for the first intake of Australia’s National Service scheme. He applied for officer training and completed the first course of the Scheyville National Service Officer Training Unit (1OTU).

In January 1966, he was posted to 6RAR and appointed commander of 12 Platoon. Dave served the full 12-month tour and was a platoon commander at the Battle of Long Tan, for which he was awarded a Medal for Gallantry (MG).