5 minute read

Chapter 5: Case Studies

from Pedestrian Mobility

by Shrey Patel

Chapter 5. CASE STUDIES

5.1 STROGET, COPENHAGEN

Advertisement

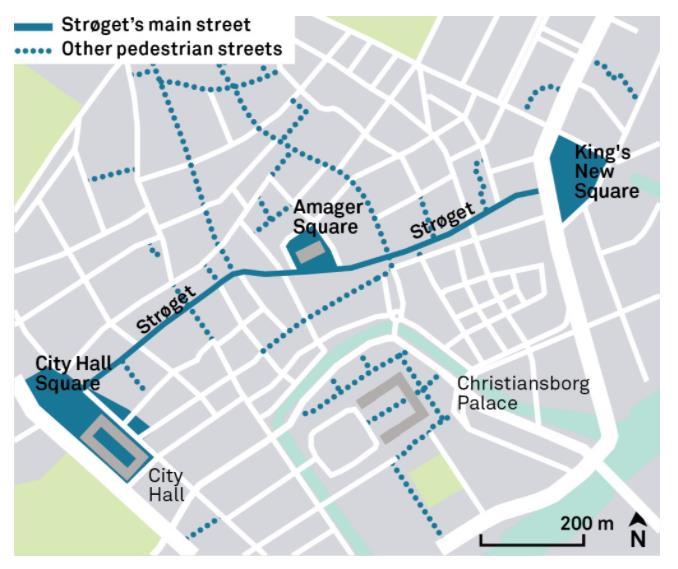

Figure 41. Location of Copenhagen (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 28, 2021) Location: Copenhagen, Denmark Population: 0.5 million Length: 1.15 km (0.7 mi) Right-of-Way: 10–12 m Context: Mixed-use (Residential/Commercial) Maintenance: Repavings since 1963 Funding: Public

5.1.1 OVERVIEW

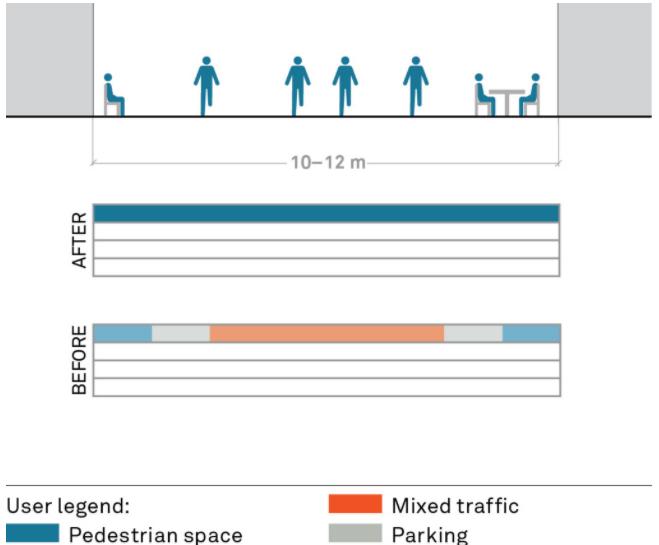

Until 1962, all of downtown Copenhagen's streets and squares were heavily used for vehicle traffic and parking, and the quickly increasing fleet of private automobiles put a strain on them. Copenhagen's pedestrianisation began with Stroget, the city's major thoroughfare, which was transformed as an experiment in 1962. The conversion of the 1.15 km-long main street into a pedestrian street was seen as a pioneering effort, which gave rise to much public debate before the street was

Figure 42. Street location in Copenhagen (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 28, 2021)

converted. “Pedestrian streets will never work in Scandinavia” was one theory. “No cars means no customers and no customers means no business,” said local business owners. Stroget quickly became a tremendous success, with businesses understanding that trafficfree surroundings generate more income. The earliest squares to be refurbished were Magasin Torv, the square opposite Nikolaj Church, and Grbrdre Torv.

5.1.2 KEY ELEMENTS

• The roadway will be closed to all traffic. • Curbs and sidewalks will be removed, and new pavement will be installed. • Pedestrian circulation will be aided by the consolidation of street furniture.

5.1.3 GOALS

• Improving the city's connection. • Create an inviting and high-quality atmosphere. • Create a business-friendly environment. • Encourage individuals from all walks of life to live and visit the city centre. • Revitalize the city's run-down alleyways by transforming them into lively laneways.

5.1.4 KEY TO SUCCESS

The successful pedestrianisation of streets in Copenhagen can be attributed, in part, to the incremental nature of change, giving people the time to change their patterns of driving and parking into patterns of cycling and using collective transport to access key destinations in the city—in addition to providing time to develop ways of using this newly available public

space.

5.1.5 EVALUATION

Figure 43. Evaluation of street Copenhagen, Denmark (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 28, 2021)

Figure 44. Before & after view of street Copenhagen, Denmark (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 28, 2021)

Strøget has been renewed and upgraded several times during its 53 years as a pedestrian street, by using progressively better-quality materials, repurposing public spaces and plazas to increase pedestrian comfort, and adding outdoor uses. Amager Square was renovated in 1993 by local artist Bjørn Nørgård. Today, it is the second most popular urban space in the city because of the diverse range of activities offered there.

5.2 FORT STREET; AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND

Figure 45 .Location of Auckland (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 29, 2021)

5.2.1 OVERVIEW

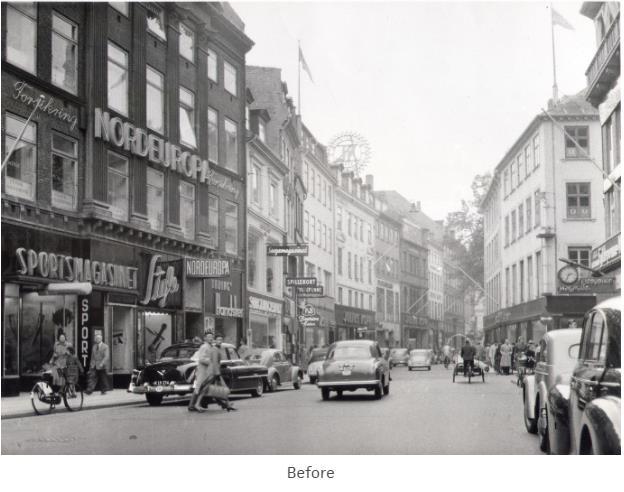

Location: Auckland CBD, New Zealand Population: 1.4 million Metro: 1.5 million

Context: Mixed-Use

(Residential/Commercial) Right-of-Way: 19–20 m Size: Area in and around Fort Street

Fort Street exemplifies how shared roadways can transform a neighbourhood into a destination, attracting more people to buy and participate in other activities. It is one among several new shared areas in Auckland's Central Business District that have been constructed

in recent years to improve pedestrian connection and offer a high-quality public realm.

5.2.2 KEY ELEMENTS

• Any barriers between pedestrians and cars, such as curbs and bollards, should be removed. • Expansion of open-air activities. • Pedestrians have full access to the right-ofway. • Accessible paths for the visually impaired along building lines. • All parking spots will be removed. • Loading times are limited. • Landscaping and street furniture

5.2.3 GOALS

• Better integrate the area into the surrounding street network. • Prioritize pedestrians. • Create a distinctive public space. • Create a space that supports businesses and residents and provides opportunities for a variety of activities. • Provide a high-quality, attractive, and durable street that contributes to a sustainable and maintainable city centre.

Figure 46. Street location Auckland CBD, New Zealand (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 29, 2021)

5.2.4 KEY TO SUCCESS

• Collaboration with key stakeholders. • Monitoring and evaluating the project before and after implementation to communicate its impacts. • Testing design variations.

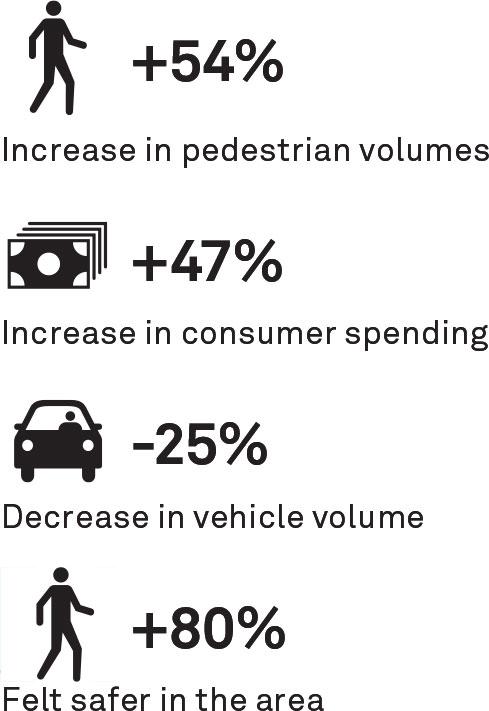

5.2.5 EVALUATION

Before

After

Figure 47. Before & after view of street Auckland CBD, New Zealand (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 29, 2021)

Figure 48.Evaluation of street Auckland CBD, New Zealand (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 29, 2021)

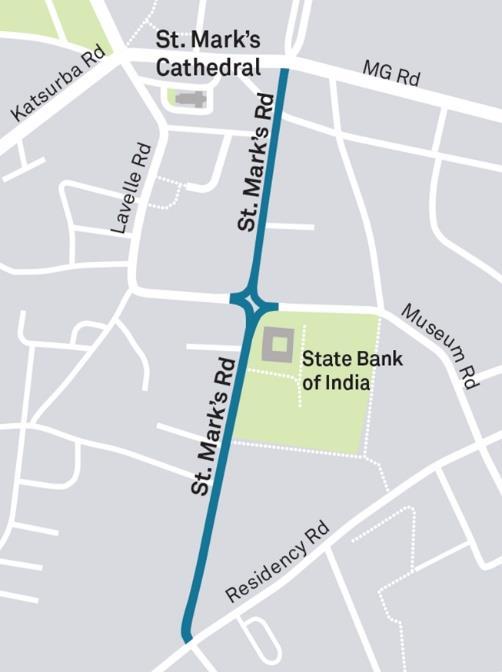

5.3 ST. MARKS RD.; BANGALORE, INDIA

Figure 49. Location of Bangalore (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 30, 2021) Location: Bangalore, India Population: 8.42 million Context: Central Business District Right-of-way: 18–20 m (on average) Length: Approximately 1 km Cost: 1.15 billion INR (20 million USD) for the first phase Funding: Public

5.3.1 OVERVIEW

Several important difficulties were addressed during the renovation of this one-way roadway, including insufficient design and planning, low maintenance standards, and inefficient utility management. Under the Tender S.U.R.E. program, the project used a holistic, multidimensional approach: break once, fix forever. This approach promotes upfront investment in quality materials and construction to increase durability.

5.3.2 KEY ELEMENTS

• Improvements and expansions to walkways. • Protected one-way cycling paths. • Consistent travel lanes. • Dedicated bus, auto-rickshaw, and parking spaces that are paved. • Between the motorised and non-powered routes, there is a landscaped strip. • Pits and guards are used to protect and enhance existing trees.

• Reconfiguration of subsurface utilities, including the construction of utility line access chambers.

5.3.3 GOALS

• Maintain a healthy balance of existing usage. • Improve the user experience, enhance pedestrian safety, and reduce traffic congestion. • Invest in the upfront, high-quality building for long-term durability to reduce disruptive construction methods.

5.3.4 KEYS TO SUCCESS

Interagency coordination. Public participation and involvement from the early stages of the project. Documentation and verification of existing utilities as part of the planning and design process.

Figure 50. Street location Bangalore, India (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 30, 2021)

Figure 51. Before & after view of street Bangalore, India (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 30, 2021)

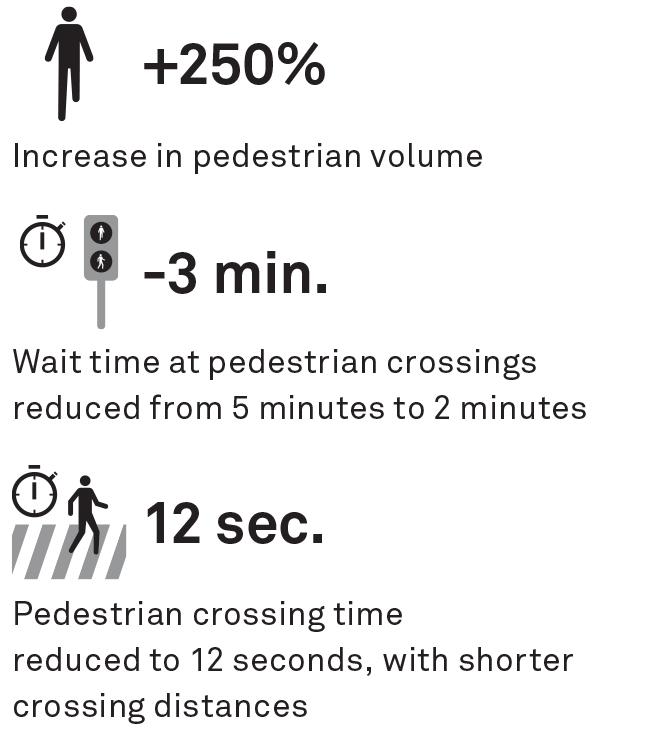

5.3.5 EVALUATION

Before

After

USE OF STREET

Figure 52.Evaluation of street Bangalore, India (source: globaldesigningcities.in) (Date: April 30, 2021)