23 minute read

Silver Linings: The Pandemic at Shore

Advertisement

Silver Linings:

The Pandemic at Shore

By Bill Fisher

It was a shot across the bow of the advancing pandemic. In the summer of 2020, on the heels of a virtual graduation and a spring spent in remote learning after a statewide school shutdown in March, Shore’s administration, Board of Trustees, and the Board’s COVID-19 Task Force resolved to open the following school year fully in person. The decision was momentous and prescient: by the end of the 2020-2021 school year, Shore would complete nine months of in-person learning, earning praise from families, employees, and students for preserving face-to-face education in spite of the pandemic odds. “Thank you to the entire Shore staf for this year,” one family wrote on social media. “Words can’t express how grateful we are for everything everyone did to allow our kids to have in-person learning since day one.”

Indeed, getting from June 2020 to the frst day of school—let alone to the following June—required an all-in efort from every corner of the Shore community. But that efort was worth it. “Based on the spring,” says Head of School Clair Ward, “we knew what our kids needed—they needed to be in person. And I knew that whatever version of that we could achieve was going to be better for children than being fully remote. My feeling was, Shore needs to do Shore.” The COVID-19 Task Force agreed. “Nearly every one of the Task Force members was a current parent at the school. They remembered what the spring had looked like for their kids, and knew what their kids needed, too,” says Ward. There were numerous challenges to face before the return to school. The frst was ascertaining whether Shore had the physical capacity to house its 350-some students safely, observing all the distancing and hygiene guidelines handed down to schools by the state’s Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. Rooms were measured; rules for nearfull-time masking were devised; empty desks and chairs were arranged six feet apart and counted; hand-washing areas were inventoried and in some cases added; air-handling systems were evaluated and upgraded; and potential outdoor classroom spaces were surveyed. In the end, the news was good: even with large areas such as the theater and Dining Hall closed to most gatherings due to virus fears, Shore’s facilities were more than adequate for safe in-person learning for the entire student population. Next, administrators had to plan for two scenarios for the fall: full in-person attendance, and the remote learning that most observers expected would return at some point as virus transmission rates spiked. “Everybody thought we would get only six to eight weeks in school, and then we would be going back to distance learning,” says Head of Lower School Sara Knox. “So we needed to maintain the momentum from “Words can’t the spring and make sure that teachers continued to express how take advantage of professional development opportunities related to distance learning, knowing grateful we are for that there was this very real possibility that everything everyone did that’s what we were going to be doing for at least a portion of the school year. At the same time to allow our kids to have we had to compartmentalize that thinking so in-person learning we could also imagine what in-person learning would look like.” since day one.” Knox and Head of Upper School Gustavo —Shore family Carrera had to completely revamp the curriculum to anticipate switches between in-person and remote learning, and they had to revise schedules to accommodate the cohort model that would be implemented to keep groups of children separate from each other, minimizing the chances of in-school spread of

COVID-19. Says Knox, “One of the things we did before we started the school year was to prioritize units in all subject areas that really required in-person teaching and learning. We shifted the curriculum at every grade level so that we could capitalize on the time that we expected to have kids in person.”

Carrera, along with his faculty, had to reimagine teaching for the cohort model. “For example,” he says, “we had to create heterogeneous math classes—groupings of students at diferent ability levels—in order to sustain social connections within the cohort. That was a challenge for the teachers, who had to deliver what were essentially multiple complete math tracks at the same time.” The revised Upper School curriculum also called for new rotations in art, music, and engineering classes. Because the teachers in these subject areas in a typical year would be exposed to the entire student body, their teaching would now have to be confned to one cohort per grade at a time, limiting the chances that one sick teacher could spread COVID-19 throughout the entire division.

By August, with planning for both in-person learning and remote attendance well underway, it was time to make sure teachers and families were on board with the return to school. Among faculty members, fear and uncertainty had been growing, as news coverage of teachers’ reluctance to return to classrooms nationwide increased. “In the case of our faculty,” says Clair Ward, “they just needed communication. They wanted to hear how we were making school a safe environment for both children and adults, and they needed reassurance that the policies and procedures we were developing for safety—masking, hand washing, physical distancing—would work in the classroom.”

Families, too, needed more communication from the school as they sought answers to their questions— especially since they would not be allowed on campus during the school year. Shore published a complete reopening plan that detailed everything from contacttracing protocols to daily health and safety procedures at every grade level. Ward also began hosting a series of webinars for families to provide even more information and updates about the school’s response to COVID-19.

“I recall the month of August being nothing but courage—courage to convince the families we could do it, courage to convince ourselves that we could do it, courage to convince the faculty that they would be okay, and that they could do it,” says Ward.

Finally, in September, over the course of three opening days, masked students arrived in stages for their frst day back at Shore since being sent home in March. In a message to families, Ward promised, “In “I recall the month of August being nothing but courage—courage to convince the families we could do it, courage to convince ourselves that we could do it, courage to convince the faculty that they could do it.”

—Clair Ward, Head of School

the extraordinary times brought by the pandemic, we recognize that our highest responsibility is doing all we can to protect the health and safety of our students, families, and employees. We will remain open for in-person learning on campus only as long as it is safe to do so.”

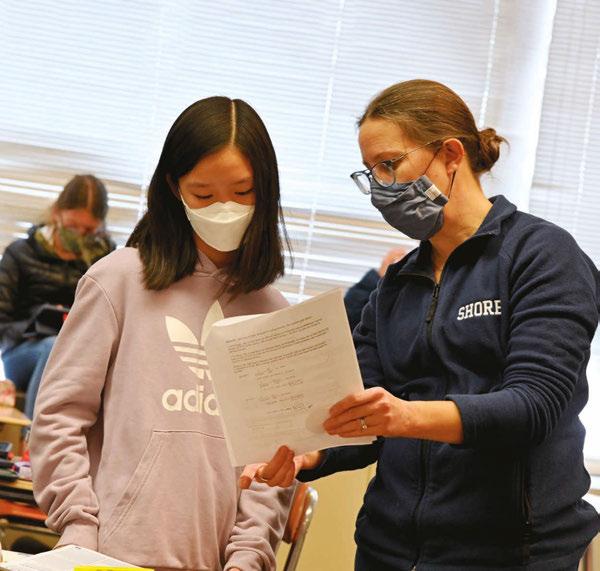

Shore’s commitment to safety meant that families had to complete a comprehensive health self-screening for their child through a mobile app called MyMedBot each day before coming to Shore. Once at school, children wore masks the majority of the time, whether in the classroom or outside, and seating arrangements were carefully mapped to maintain social distancing. Throughout their school day, children remained with a single homeroom or cohort, a group of 10-16 students with dedicated indoor and outdoor spaces and little contact with other groups of students. Signage and foor markings enabled safer, one-way trafc fow in the school’s hallways, and extensive new cleaning protocols and windows and doors propped open to allow fresh air fow followed CDC and Massachusetts state guidelines for combating the spread of the virus.

Despite the new procedures that afected nearly every aspect of life for both children and adults at the

school, “Shore still felt like Shore,” says Clair Ward. “When you ask someone what is special about Shore, they usually repeat some version of, ‘It’s the people.’ Watching the faculty and staf embrace the planning and training and excitedly welcome the students back during the opening days made the ‘people factor’ even more noticeable.” Over the frst days of school, teachers rolled out protocols for frequent hand washing in ways that even the youngest students could understand; they introduced older students to tented outdoor learning areas that faculty and staf had worked together to construct in order to provide students with as much fresh air as possible; and they explained how Shore hallmarks such as daily recess, regular art, music, and language classes, outdoor education, and the Upper School advisory system—though modifed for safety’s sake—would remain part of the routine.

The children, for their part, seemed to take all the new policies and practices in stride, glad to see their friends and teachers in person again despite the “new normal” of mask wearing and social distancing. “It was

easy to get distracted or worried by the ways in which everyone feel safe.” children’s experiences could be compromised by all the measures we had to take to ensure the safety of our —Gustavo Carrera, Head of community, but seeing the children happy to be on Upper School campus made all the diference in the world. The joy we experienced at being together back at school was palpable,” says Ward. “When the year began,” elaborates Sara Knox, “it was an all-in feeling. The energy was so genuine, and there was this all-hands-on-deck mentality. Teachers supported each other, sharing their resources, time, and labor. We all felt proud, because we knew that so many schools were not able to start in the way that we were.” In-person school required faculty members to adapt in countless ways. Spending much more time outdoors was one of the most noticeable changes. According to Gustavo Carrera, “Outdoor time, whether it was an outdoor class or just time for lunch and recess, was helpful for both students and teachers. The fresh air made everyone feel safe. Pedagogically speaking, we noticed that being outdoors inspired greater engagement on the part of the students. Both they and their teachers really enjoyed being outside under a tent or in the sun just having a conversation or eating lunch.” Sara Knox says, “Our teachers had to read the room even more closely than ever before, noticing when kids

needed a break from the confned space of the homeroom. They could give one student or a whole class a few moments outside—time enough for them to reset and be ready for learning again.”

Technology was another area where teachers had to adapt to the new circumstances. Because of the concern about touching and sharing paper and other materials in the classroom, says Knox, “We made digital versions of a lot of things that were traditionally on paper, so that kids could access everything they needed on their iPad. A lot of teacher time went into that digital transformation, but it paid of. We were able to shift from what was in some cases an outdated worksheet model to an approach where children could independently access their work and manage their own learning on a device. Things like commenting and sharing through Google Drive happened more in the Lower School than they’ve ever happened before.”

In the Upper School, says Gustavo Carrera, teachers turned to digital technology to ofer greater diferentiation of instruction within each cohort. “Learning platforms like Showbie, an iPad app for creating and completing assignments, allowed for the kind of engagement that sometimes a student could not fnd in the classroom, because it gave them the independent thinking time they needed to respond at their own pace.”

One adaptation was required of teachers in both Upper and Lower schools. This was the use of a rolling cart to transport teaching materials. Because Upper School cohorts remained in their classrooms for the majority of the day, instead of moving between individual subject teachers’ rooms as in a normal year, this year the teachers had to go mobile, transporting supplies, projects, art materials, books, and more between cohort rooms on rolling red carts that became a familiar sight in the hallways. Similarly, in the Lower “Wemade School, special subject teachers in art, digital versions music, Spanish, and S.A.I.L. (Science and Art Integrated Learning)—who of a lot of things that in a normal year would see students were traditionally on paper, as they traveled to their dedicated special subject teaching spaces— so that kids could access had to travel between homerooms everything they needed where students spent the majority of their day. The rolling red carts on their iPad.” became a familiar sight in the Lower —Sara Knox, School, as well. Head of Lower School All of Shore’s employees had to step up in one way or another as the school adapted to the circumstances of the pandemic. When all-school weekly COVID-19 testing began in January, for example, members of the staf volunteered to help administer the tests in the Lower School and to package and sort kits for employee self-service testing. The Maintenance Department followed rigorous daily cleaning procedures, and the Dining Services staf delivered packaged meals to homerooms and cohort rooms throughout the school. As the year went on and Shore experienced its frst positive cases of COVID-19 among students, teachers,

and families, the school’s safety protocols appeared to be working. Afected homerooms or cohorts were quarantined at home as needed—with Zoom enabling distance learning to continue—and there was no evidence of in-school transmission of the virus. Shore remained open, much to the surprise of many. And so months into the reopening, the question became not whether the school could sustain in-person learning, but whether the experience could be improved. “We started to notice what we were missing,” says Sara Knox. “We couldn’t bring everyone together in the theater. We couldn’t have all-school House meetings. What could we do to sustain the school community when we couldn’t all be together in the ways we were used to?”

Fifth grade teachers, along with their Kindergarten and Pre-Kindergarten colleagues, shared one idea with Knox. The Big Buddies program brings together ffth graders with Kindergarten and Pre-Kindergarten students for reading, games, activities, and more—but during a pandemic year in which cohorts and homerooms had to remain separated, none of these was possible. Teachers asked Knox whether they might reimagine the Big Buddies program to meet the safety protocols that were in place, which called for 14 feet of distance between cohorts. “There were a lot of conversations about what we could do that felt safe,” says Knox. “The frst time they got together, they were outside on the feld, they had measured the distance between groups with a measuring tape, and they were playing a no-contact call-out game.” Later in the year, they used Zoom to stay in touch across classrooms, and they even enjoyed a pen pal program.

Elsewhere around the school, students and teachers were fnding similar ways to connect with each other safely and sustain school spirit. Music teachers Jenn Boyum and Alex Asacker orchestrated virtual concerts and talent shares via Zoom, and House captains arranged competitions, crafts, and video events for Upper School cohorts. Video Morning Meetings that featured classroom presentations and other forms of student participation delighted Lower Schoolers each week.

Just as maintaining connections within the school required extra efort, so did keeping families, who were not allowed on campus, in the loop. “We missed the families in the building; we missed them on the felds and in the theater,” says Gustavo Carrera. “The families, too, missed the opportunity to see their children at work in the ways in which they had in the past.” To engage families, Upper and Lower School teachers turned to Zoom conferences, frequent phone

— Gustavo Carrera

— Gustavo Carrera

calls, and regular e-mails about what was going on in the classroom.

“We had to work even harder at communication than we normally do,” says Sara Knox, “because I think, in a normal year when there are families on the curb at carpool or in the Kiva, or coming into the building to do something special in a classroom, very quick, informal face-to-face check-ins are common. Families can get a sense of what’s happening and how their child is doing. This year, we learned that we had to communicate much more. I think part of it is that families didn’t have a visual—they wanted to picture it more, and the only way that could happen was for us to fnd more touch points.”

The extra efort clearly paid dividends. One innovation in the Upper School, the student-led parent-teacher conference, was universally praised. “By allowing the student to paint the picture of what the school year looked like,” says Gustavo Carrera, “the families learned about their lives at Shore in a totally diferent way. Particularly this year, it was so important for families to hear from the children themselves what the experience was like, rather than mediated by the teacher or an advisor. I heard from families afterwards that the student-led conference was something that made them very proud of their kids.” Still, the pandemic took its toll, not only on the connections between families and school, but on students and employees themselves, some of whom struggled with anxiety triggered by a long winter spent masked and indoors, never certain when the next case of COVID-19 in the school would be announced. “We defnitely had to attend to everyone’s mental health throughout the year,” explains Clair Ward. “I would say that the children’s mental health ebbed and fowed, and I would say the employees’ and the families’ mental health ebbed and fowed, as well. Among our families, there were circumstances that made managing school and personal life very challenging— issues around childcare and remote working adding to the stress of the pandemic itself.” “At every grade level,” adds Sara Knox, “we had at least a handful of kids who were really struggling with anxiety. All of those instances required a lot of conversations and planning sessions that involved the teacher, me, School Counselor Katie Hertz, and the families, and sometimes even an outside counselor.” COVID-19 may not have been the sole cause of the anxiety, admits Knox, but it played a role. “When school is so diferent, and children aren’t able to see their friends outside of school, it becomes a lot to cope with.”

As the year went on, employee exhaustion, too, became a factor. It was the pandemic, but it was more than that. “When I think about individuals at this school and the contributions that each person made this year that were above and beyond the call of duty,” says Knox, “it’s easy to picture a person and name three to fve things they did that went far beyond just pitching in and being a helper. I think it’s worth saying again and again that there’s no way that we would have been able to do what we did this year if we didn’t have everybody on board, thinking the same way. The attitude was, ‘We’re going to do this.’ But it’s a long time to push with that mentality, and that leads to exhaustion.

Everybody’s going for the A-plus, and it’s not just a month of that; it’s a year-plus. You hit a wall.”

Yet by the spring, the worst of the pandemic in Massachusetts seemed to be fading, and the mood on campus was lifting. Shore’s weekly COVID-19 testing, which had been required for all students and employees since January, was returning acrossthe-board negative results week after week. Beloved Shore traditions such as Head’s Holiday and Field Day brought the school together outdoors, and, though students and teachers remained masked, their joy was evident. “What I felt in these events was relief,” says Clair Ward. “I felt relief that I could see and hear and taste the joy that wasn’t so easy to sense at times during the previous year. And at a time when the rest of the world was politicizing masks or vaccines or other kinds of national divisions, what I saw was nothing but gratitude from all of our community members, relief that this was an oasis of sanity and joy for kids.”

Shore families, for their part, had, with few exceptions, been supportive of the school’s COVID-19 response, and they went out of their way to express their appreciation. Throughout the year, the Shore Parents Association arranged small gestures, such as the delivery of fowers to all employees, to demonstrate their gratitude and buoy spirits. The Chair of the Parents Association, Michele Vaccaro, wrote, “The Parents Association is extremely appreciative for all that Shore faculty and staf have done for our school, our children, and our community. They have worked tirelessly, and we will always remember everything they have done to get through this year.” Other families sent notes of thanks to individual employees.

If gratitude and joy were silver linings of the pandemic, so, too, were other discoveries that came throughout the year.

According to Sara Knox, “So much about how we teach has shifted and changed for the better since last spring. In terms of technology platforms and project types, our teachers have just had to dive in and start using all kinds of new tools and approaches which would have taken us much longer to get to had it not been for the pandemic.” Technology has also enabled new forms of communication with families that may well stick around after the pandemic “There’s something to be said for the Zoom parent conference or grade-level parent cofee,” says Knox, “or If gratitude and joy were silver linings of the pandemic, so, too, were other discoveries that came throughout the year.

the admissions event that’s virtual, rather than in person. Attendance is simply better, and easier for families; guests can tune in from wherever they are.” Gustavo Carrera agrees, “We learned that technology can provide a very robust experience, both for students and for families.”

If there is one silver lining from the year that stands out for Carrera, it is what he’s learned about nimbleness. “We did not over-plan, which served us well, because during the pandemic we had to change our plans several times and, for example, remain fexible in the face of unexpected quarantines. This allowed us to give more freedom to our teachers to solve problems in their own way, and it allowed us to honor the student experience—beyond simple content delivery.” As an example, Carrera explains how teachers were empowered to make one-on-one connections with students, despite the limitations of the cohort system and the yearlong requirement for social distancing. “What you saw was teachers meeting

individually with students in the hallways, where open doors to the outside meant that fresh air was continually fowing. We could have over-managed these situations by limiting the use of the hallways, but I believe that would have created less of a sense of safety and less of a sense of empowerment.”

Clair Ward identifes another silver lining of the year. “I think we actually provided more inclusive access to the school because of the more frequent virtual communications we made available—people had more access to the partnership between home and school, even alumni and the families of alumni that desperately want to maintain their connection to Shore. The pandemic provided that opportunity and taught us how important that connection is, and how our larger Shore community is just waiting to be asked, waiting to be connected. That’s something we want to hold on to.”

Beyond silver linings, Ward sees the pandemic as a test for Shore, “a test to see if we as a community could be fexible, strategic, focused, and caring. And I believe we have proved ourselves—we all know some things about Shore that we didn’t know before, about our capacity and our adaptability. In other words, if we can be successful in a 15-month chapter like this one, then when it comes to executing our strategic plan, or looking at ways to make Shore more sustainable, more inclusive, the pandemic has proven to us that we have what it takes to be successful in those realms, too.”

Ward continues, “So to me, the story of this year isn’t so much COVID-19 as it is how COVID-19 provided an extreme proving ground for the behaviors we need to be successful as an organization and as a community—the behaviors of innovation, courage, nimbleness, and fexibility. The data demonstrate that we were successful in all the important ways. We had no in-school transmission of the virus—a testament to all of our protocols and weekly testing. Academically, because of the way we built our schedules, the children ended up right where they should have been by the end of the year—there was virtually no impact on learning, and that’s backed up by our standardized academic test results.”

“The year was successful because it provided a vibrant school experience, against all odds,” elaborates Gustavo Carrera. “Academically, emotionally, students were challenged, and they thrived. I have an enormous amount of respect for my colleagues, but more than that, I’m really in awe as to what they pulled of.”

Employees—and beyond them, the families—are the “good bones” that the pandemic revealed, according to Clair Ward. “With the caring, the nimbleness, and the bravery that came to the forefront during the year, we’ve received a real injection of confdence in what we are capable of. Armed with what we’ve learned from the pandemic, I believe we’re now prepared to make incredible strategic progress in the years to come.” “The year was successful because it provided a vibrant school experience, against all odds. Academically, emotionally, students were challenged, and they thrived. I have an enormous amount of respect for my colleagues, but more than that, I’m really in awe as to what they pulled of.”

— Gustavo Carrera