10 minute read

CHARACTER OF THE VOIDS

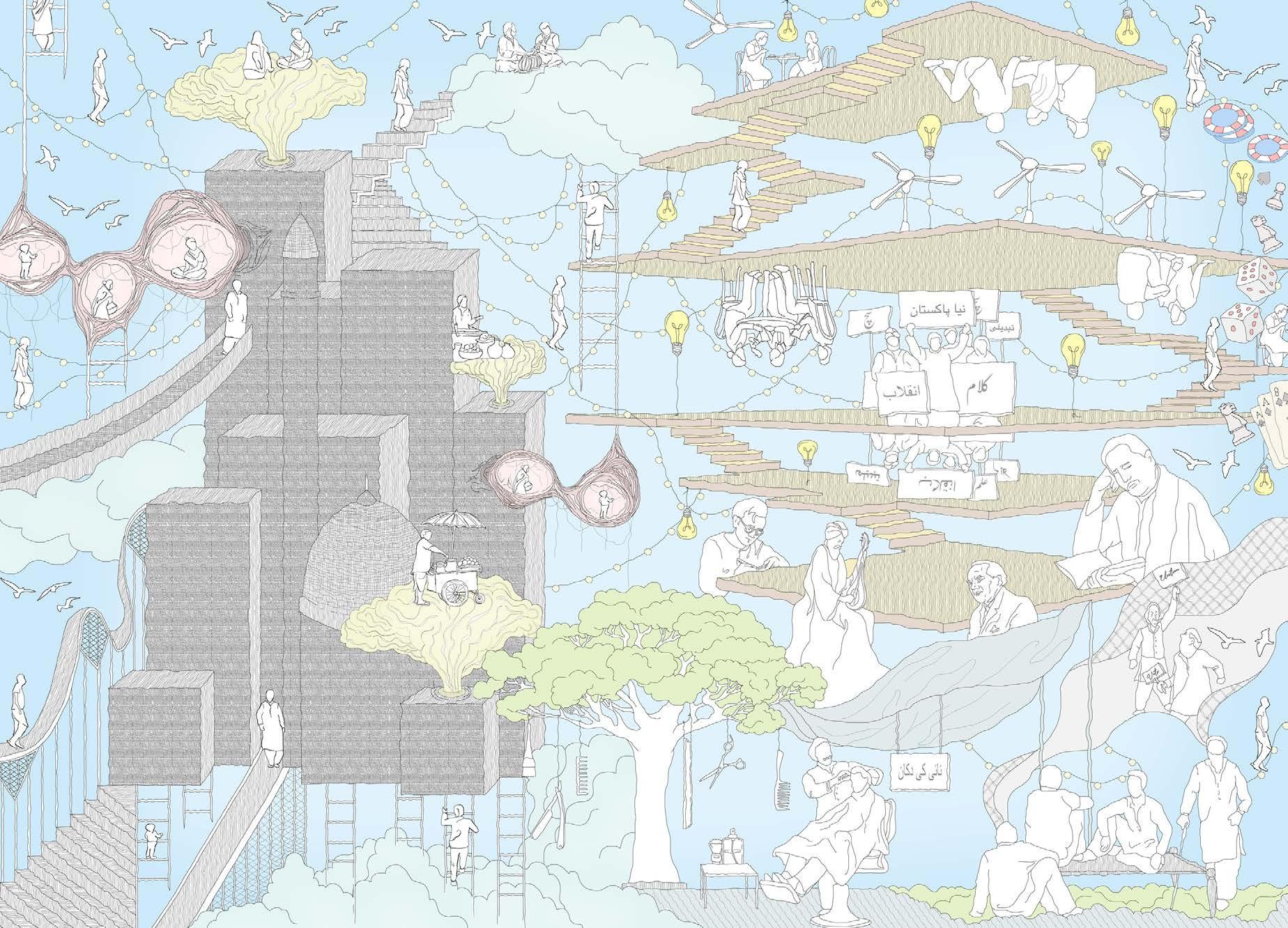

A throng of birds soaring over the Walled City do not view the streets amidst the built structure as organized, straight lines.

Advertisement

The character of these voids lies in its topsy-turvy form. Within these nooks and corners, the encroachments by residents and shop owners occur. Encroachments around which people gather and connect.

ATROCIOUS ENCROACHMENTS

Encroachments are defined as intrusive advancements beyond usual or acceptable limits (Merriam-Webster n.d.). They are viewed as barbarities, violating the public spaces, and sluggishly spreading their clammy tentacles over the built spaces and voids alike.

The large corporations and clever businessmen, illegally collaborating with the government authorities, are encroaching heavily upon public spaces in the Walled City like rapidly spun spider webs. Meanwhile, the small shops extending a few racks of chips, and the residents placing a charpoy along the street, are frowned upon as an infringement of the public right.

EXTENSIONS; NOT ENCROACHMENTS

In most parts of the world, this act of taking over public spaces is an illegal encroachment. In the context, however, it is an extension of homes, shops, and restaurants. It is a part of the heritage of the Walled City. These extensions, sprouting out of buildings, are the steps upon which the diverse actors of the Walled City connect, where the hawkers rest, the shop-owners of small familyrun businesses share their meals, and the community builds.

The laws and policies dictating the scale, intent, and sensitivity of these ‘encroachments’ can erase the negative connotation of illegality and greed from the rich legacy of extending your homes, shops, and hearts.

THE FRUIT SHOP, ROLLING DICE, CARROM BOARD, AND CRICKET

Ahmed sprays the variety of mangoes with water to keep them gleaming in hues of yellow and gold, attracting customers and encouraging the sale. His fruit is always fresh and juicy. He knows most of his customers personally and wouldn’t want low-quality products consumed by his friends. Ahmed loves what he does –running a small family-run fruit shop, right under his house. His wife slings down warm food in a bucket at 2 pm. Lunchtime is a little late for Lahoris, and every meal is prolonged with lingering conversations. Ahmed places a charpoy, outside his congested shop, extending his space. His neighbors, friends, and other shopowners join him on the extension with their lunch boxes to share their meals, wholehearted chatter, and tête-à-têtes.

As the time to close the shops begins, these extensions outside the shops are flocked by the shop-owners, ready to smoke hookahs and partake in their favorite communal activity of playing board games and cards.

Friendly gambling, otherwise heavily frowned upon in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, over flicking carrom boards, games of ludo turned upside down over lost matches, flashing cards and rolling dice commence. Meanwhile, Khalid and Muhammad play cricket, dreaming of one day making the International Cricket Team.

An array of social activities adorns the streets, within what some claim are illegal encroachments. I, however, refer to them as extensions.

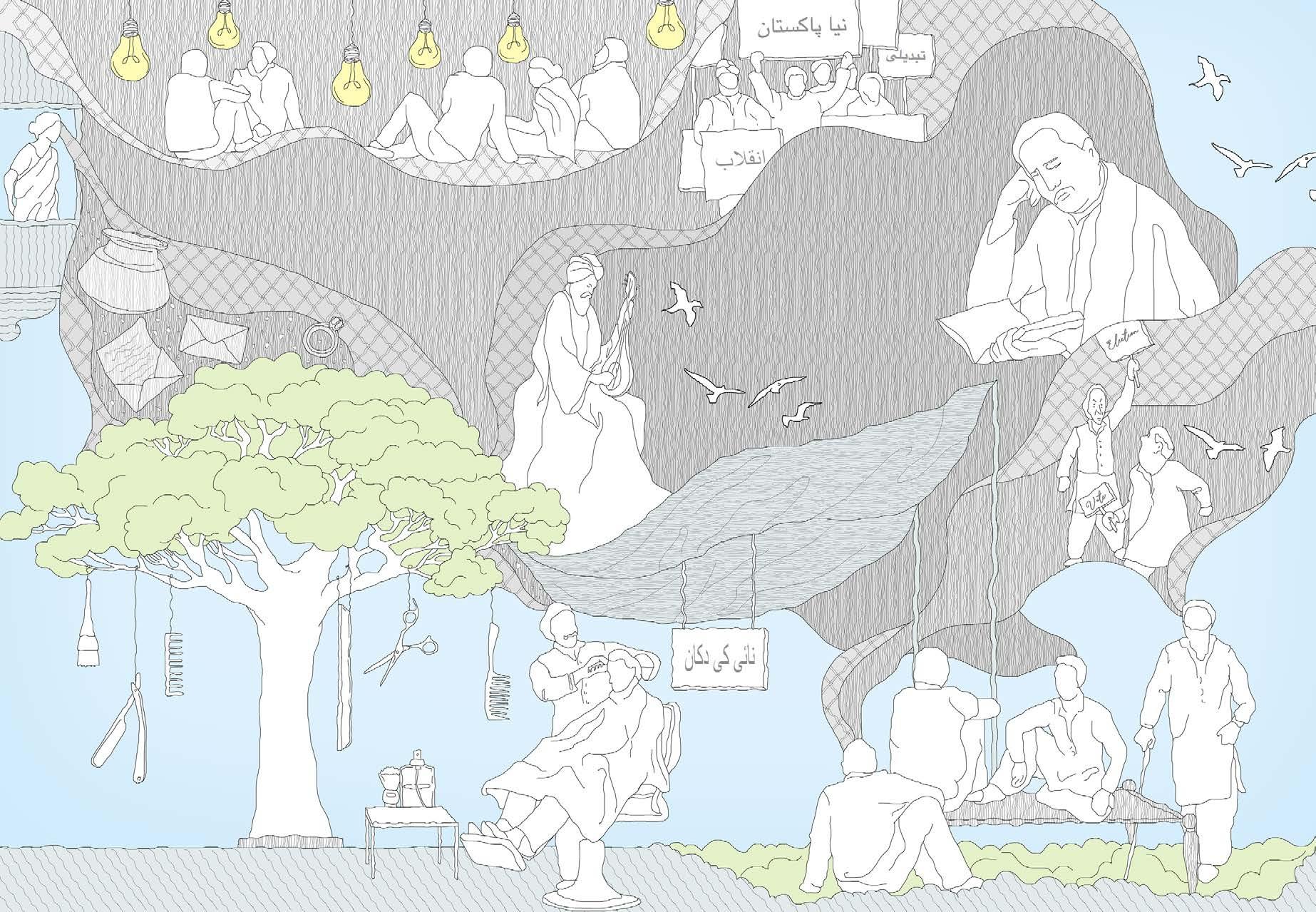

NAAYI KI DUKAAN (THE BARBER SHOP)

Another ‘encroachment’ that blossoms under a tree, is the much-favored Naayi Ki Dukaan, (the barber shop). A barber plays many diverse roles in the Walled City. He cuts hair, grooms beards and collaborates with the sly match-making ladies of the Inner City to unite people in arranged matrimony. He delivers wedding invitation cards, cooks meals for large gatherings, provides juicy gossip, and for some reason, performs circumcisions!

It is also in his shop that people often gather after a rough day at work and take out their stress by criticizing the system and partaking in political banter – chatter that develops into discussing philosophies. One man shares a stanza he cherishes from the poetry of Allama Iqbal, while the other elaborates upon the mysticism of the Sufi Saint, Bulleh Shah. A young woman shares with her encouraging audience, a prose she composed.

Some people scatter around discussing why women do not gather often enough in the Naayi Ki Dukaan. Maybe they should be made to feel more comfortable in these male-dominated spaces. Perhaps, the young boy residing along the corner of the street, doing his master’s degree in Urdu Literature, should write a book about it. Should they conduct a peaceful protest to create awareness about this pressing social issue?

The barbershop is not just a skilled hair-stylist in the Walled City of Lahore – he is an integral pillar of the community, and what his semi-open kiosk represents in the context reminds me of the Pak Tea House.

SWEET TEA, SPICY BIRYANI, AND REVOLUTIONARY IDEAS.

At a few minutes’ walk away from my undergrad university, gracefully concealed behind creeping ivy, rested my safe haven - the Pak Tea House. Along the periphery of the Walled City and amidst the chaotic Neela Gumbad and the Anarkali Bazaar, the Pak Tea House is a heterotopia – a sanctuary to rest, contemplate, create, discuss, share revolutionary ideas and think freely. Pak Tea House is a tea-café known for its left-leaning South Asian intelligentsia. It is recognized as the birthplace of the influential literary movement and the Progressive Writers’ Association.

Traditionally frequented by the country’s notably artistic, cultural, and literary personalities, it was founded by a Sikh family in 1940. Pak Tea House quickly acquired its current name after it was leased to one of the locals in Lahore, following the partition of India in 1947. The place was visited, often, by the likes of Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Ibn-e-Insha, Ahmed Faraz, Saadat Hasan Manto, and Intezar Hussain.

Pak Tea House is commonly described as the house of writers and thinkers, who serve the nation selflessly. The once-revolutionary space has maintained a reputation as a forum for people of diverse backgrounds to voice their opinions in an apolitical atmosphere and is treasured by the progressive individuals of Lahore (Khalid 2017).

IMAGINE COLLABORATION

Often, I see subtle glimpses of the essence of the Pak Tea House in the peaceful encroachments forming unfitting patterns across the rickety streets of the Walled City. The social interactions, bickering bargains, tattling tales, hollering hawkers, singing buskers, blossoming romances, and settling disputes, organically develop into political discussions, philosophical viewpoints, contemplative thoughts and revolutionary ideas. These encroachments are the heart of the communal culture of the Walled City. They are the medium connecting people, allowing the diverse set of characters in our story to co-exist and grow – while co-sharing meals, ideas, art, experiences, and ideologies. Amidst the labyrinth of dense alleyways, the cauldron of activities, and within the constricted open spaces of the Walled City, I imagine collaboration.

REFERENCES

AKCSP. 2018. MCRP. Lahore: AKCSP, WCLA. Ali, Reza H. 1990. „ Urban Conservation in Pakistan: A Case Study of the Walled City of Lahore.“ In Architectural and Urban Conservation in the Islamic World, von Karen R. Longeteig, eds. Abu H. Imamuddin. Geneva: The Aga Khan Trust for Culture. Annemarie S. Dosen, Michael J. Ostwald. kein Datum. „Prospect and Refuge Theory:

Constructing a Critical Definition for Architecture and Design.“ The International Journal of Design in Society (Common Ground Research Networks) 6 (1): 9-24. Appadurai, A. 2002. „A Conceptual Platform.“ In UNESCO Universal Decleration on Cultural Diversity, von K. Stenou (ed.), 9-16. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. Arnstein, Sherry R. 1969. „A Ladder of Citizen Participation.“ Journal of the American Planning Association 35 (4): 216-224.

Assi, E. 2008. „The Relevance Of Urban Conservation Charters in the World Heritage Cities in the Arab States.“ City & Time 4 (1): 5. 57. Boo, Elizabeth. 1990. Ecotourism: The Potentials and Pitfalls. Washington, D.C.: World Wildlife Fund. Coates, Gary J. 2015. Deep Beauty; Toward a Sustainable and Life-Enhancing Architecture of Place. Kansas State University.

Curzon of Kedleston, George Nathaniel Curzon, Marquess, 1859-1925. 1900. Speeches by Lord Curzon of Kedleston. Bd. 1. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Govt. Print. Ezdi, Rabia. 2007. The Dynamics of Land-Use in the Lahore Inner City: A Case of Mochi Gate . Thesis, Rotterdam: Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies. Glover, William J. 2008. Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Harvey, David, und Jim Perry. 2015. The Future of Heritage as Climates Change: Loss, Adaptation and Creativity. Lonon and New York: Routledge. Hasan, Arif. 2002. „Urban Change: Scale and Underlying Causes. The Case of Pakistan.“ Haywood, K.M. 1988. „Responsible and responsive tourism planning in the community.“

Tourism Management 9 (2): 105–108.

Hosey, Lance. 2012. The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design. Island Press.

Jacobs, Jane. 1958. „Downtown is for People.“ Fortune.

Jamal, T.B. and Getz, D. 1999. „Community roundtables for tourism-related conflicts: The dialectics of consensus and process structures.“ Journal of Sustainable Tourism 7 (3–4): 290–

313.

kein Datum. Merriam-Webster. Zugriff am 2020. https://www.merriam-webster.com/ dictionary/encroach.

Khalid, Haroon. 2017. Zugriff am 2020. https://scroll.in/article/853907/over-cups-of-teaand-conversation-at-pak-tea-house-lahore-emerged-as-the-countrys-cultural-capital.

Koch, Ebba. 2010. „The Mughal Emperor as Solomon, Majnun, and Orpheus, or the Album

as a Think Tank for Allegory.“ Muqarnas Volume XXVII: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World 27: 277-311. Lynch, P.A. 2005. „Reflections On The Home Setting In Hospitality.“ Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 12 (1): 37-49.

McIntosh, Jane. 2008. The Ancient Indus Valley. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. Merriman, Nick. 1991. Beyond the Glass Case: The Past, the Heritage and the Public, Second Edition. Leicester University Press.

Mishra, Shuchi. 2016. „Understanding the Change in Character of Courtyards.“ https:// shuchimishra.wordpress.com/2016/01/09/understanding-the-change-in-character-of

courtyards/.

Murphy, P.E. 1985. Tourism: A community approach. New York and London: Methuen. Nevile, Pran. 1993. Lahore: A Sentimental Journey. New Delhi: Allied Publishers.

Parvez, Amjad. 2017. „Old-city Lahore: Popular Culture, Arts and Crafts.“ Bāzyāft-31 (Urdu Department, Punjab University) 21-33.

Paul Jenkins, Joanne Milner and Tim Sharpe. 2009. „A Brief Historical Review of Community Technical Aid and Community Architecture.“ In Architecture, Participation and Society., von Paul Jenkins und Leslie Forsyth. Routledge.

Rab, Samia. 1998. „Rehabilitatin Historic City Centers: A Critique of an Important Modernist Assumption Underlying the 1950’s Master Plan and the 1980’s Lahore Urban Development

and Transportation Study in Pakistan.“ 1998 Acsa International Conference. Washington, D.C.

Reynolds, John S. 2002. Courtyards: Aesthetic, Social, and Thermal Delight . New York, NY: John Wiley. Roquet, Vincent, Luciano Bornholdt, Karen Sirker, und Jelena Lukic. 2017. Urban Land Acquisition and Involuntary Resettlement: Linking Innovation and Local Benefits. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Ruskin, John. 1849. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. Smith, Elder & Co. Sidhwa, Bapsi. 2012. The Pakistani Bride. New York: Milkweed Editions. Smith, Laurajane. 2006. The Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge. Sohail, Jannat. 2020. Conservation-Led Marginalization: Making Heritage in the Walled City of Lahore. Thesis, Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts.

Thapar, Bindia. 2004. Introduction to Indian Architecture. Periplus Editions (HK) Limited.

UNESCO. 2001. 2. November. Zugriff am 2020. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ ID=13179&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Urry, John. 1990. The tourist gaze: Leisure and travel in contemporary societies. London: Sage

Publications.

Wilkinson, Sara J., und Tim Dixon. 2016. Green Roof Retrofit: Building Urban Resilience. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. Zulfiqar, Zain. 2018. „Tracing the Origin of Jharokha Window used In Indian Subcontinent.“ Journal of Islamic Architecture 5 (2): 70.

THE END