5 minute read

DOUBTS CREEP IN AS A DETECTIVE SPRINGS HIS TRAP.

BY JOHN WILKENS

Kevin Brown didn’t do well under pressure. Bullied as a child, anxious and depressed for much of his adult life, the 61-year-old retired police criminalist had suffered consequences at work and at home for failing to stand up for himself

Advertisement

Now unbeknownst to him he was in the crosshairs of two veteran San Diego detectives investigating the brutal murder of a 14-year-old girl at Torrey Pines State Beach in 1984

Recent DNA tests had identified Brown’s sperm cells on vaginal swabs collected during the autopsy of Claire Hough. The cold-case detectives, Michael Lambert and Lori Adams, had spent a year quietly looking into Brown’s background and that of another man, Ronald Tatro, whose DNA had also shown up in the evidence Tatro was literally a dead end, though drowned in a river in Tennessee in 2011 So the detectives focused on Brown.

On Jan. 9, 2014 they arrived unannounced at his Chula Vista home and asked for his help on some old murders of prostitutes. This was a ruse to get inside and get him talking.

Brown had spent 20 years working in the San Diego police lab leaving in 2002, 10 years before the DNA hit. His career there was cut short by poor performances during courtroom testimony One of his bosses said defense attorneys would “beat him up pretty good” during crossexaminations, get him to back away from his findings.

The detectives spent a couple of hours asking about Tatro Brown said he didn’t know him and then steered the interview to Hough. They showed Brown her photo and he said “Oh, I remember her.”

“Did you ever meet her?” Lambert asked.

“No, not personally,” Brown said. “I just remember the picture looks familiar.”

Police interrogations are like ladders: Rung by rung, detectives try to move a suspect uphill in the direction of confessing. They know that a suspect saying “I did it” can be powerful evidence. But confessions are also problematic; false ones are a leading cause of wrongful convictions.

Here, by admitting some familiarity with Hough, Brown had taken the first step up the ladder Her murder was big news when it happened, and it had been revisited in the media numerous times over the years, so Brown wasn’t the only person in San Diego who would have recognized her picture. But the detectives weren’t going to leave it at that

They asked Brown whether he was the criminalist who analyzed the Hough evidence in 1984 they already knew he wasn’t and he said he couldn’t remember all victims in the cases he worked.

There was some discussion about how the lab was set up back then, before DNA tests came along and could identify suspects from the tiniest bits of blood, saliva and other bodily fluids.

Then Lambert dropped a bombshell “The issue that we have with this case,” he told Brown, “is that in some of the evidence your DNA showed up.”

“Who?” Brown asked.

“Yours,” Lambert said. Brown said contamination must have happened: “I had my hands in a lot of things there.”

Detectives knew that Brown’s DNA was from sperm cells, but they didn’t tell him that, letting him wonder out loud if maybe he had touched her clothing or breathed over it while a criminalist nearby examined the evidence. He said they didn’t always wear masks or gloves.

Eventually he asked, “Do you know how it got where my evidence is?”

“Yes,” Lambert said “Your evidence was on vaginal swabs.”

“What?” Brown said.

“And it was sperm,” Lambert said. “It wasn’t touch DNA it wasn’t saliva.” The detectives sharpened their approach. “We know that you were there,” Adams said. “How else would your semen get inside her?”

“There’s only one way, Kevin, Lambert said.

“I know, Brown said. “I’m not that dumb.”

This would have been a moment for Brown to point out that criminalists commonly brought their own semen into the lab, deposited on pieces of cloth so it could be used to test the efficacy of sperm-detecting chemicals. But he didn’t.

Instead, he wondered out loud if someone planted his semen, although he couldn’t explain how that was done, or who would want to do it. Detectives told him contamination of any kind had been ruled out.

“Did you have sex with her?”

Lambert asked.

“I don’t even remember if I did,” Brown said, adding a few minutes later “I don’t know how I don’t remember I don’t remember every person I may have been sexually intimate with, but I do know that I’d never, ever kill anybody.”

The detectives brought up Tatro again, and offered possible scenarios. “Maybe,” Lambert said, “you

U.S. DISTRICT COURT

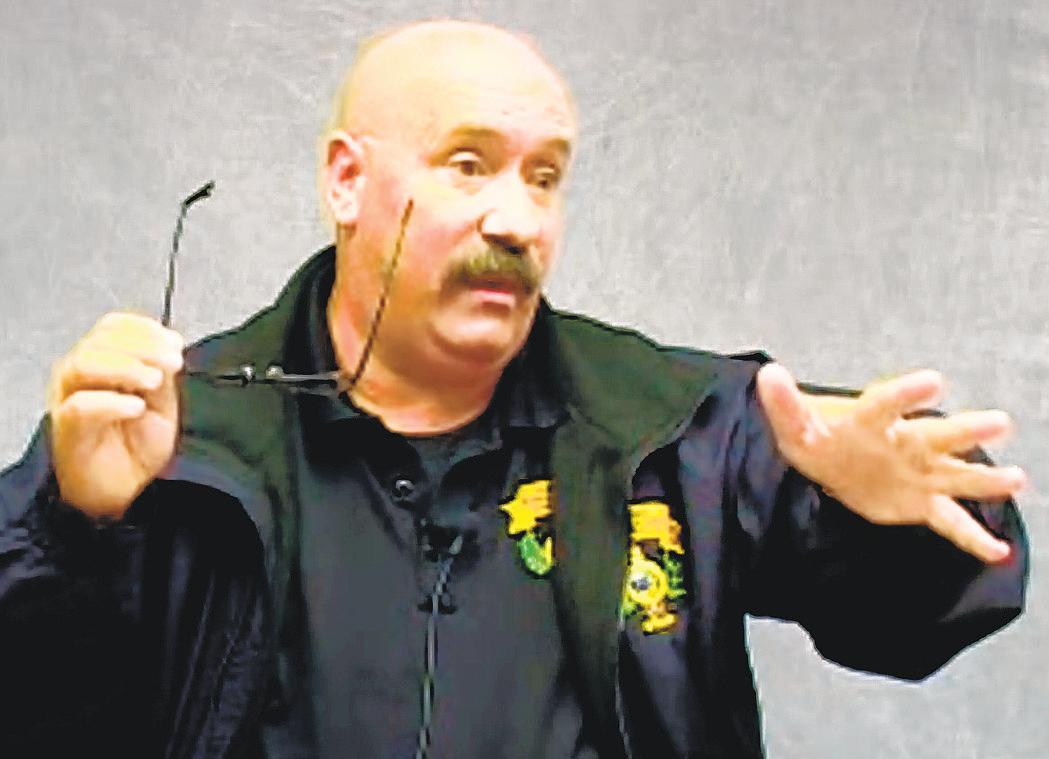

Michael Lambert, seen here during a videotaped deposition, was the lead investigator on the Claire Hough cold-case murder.

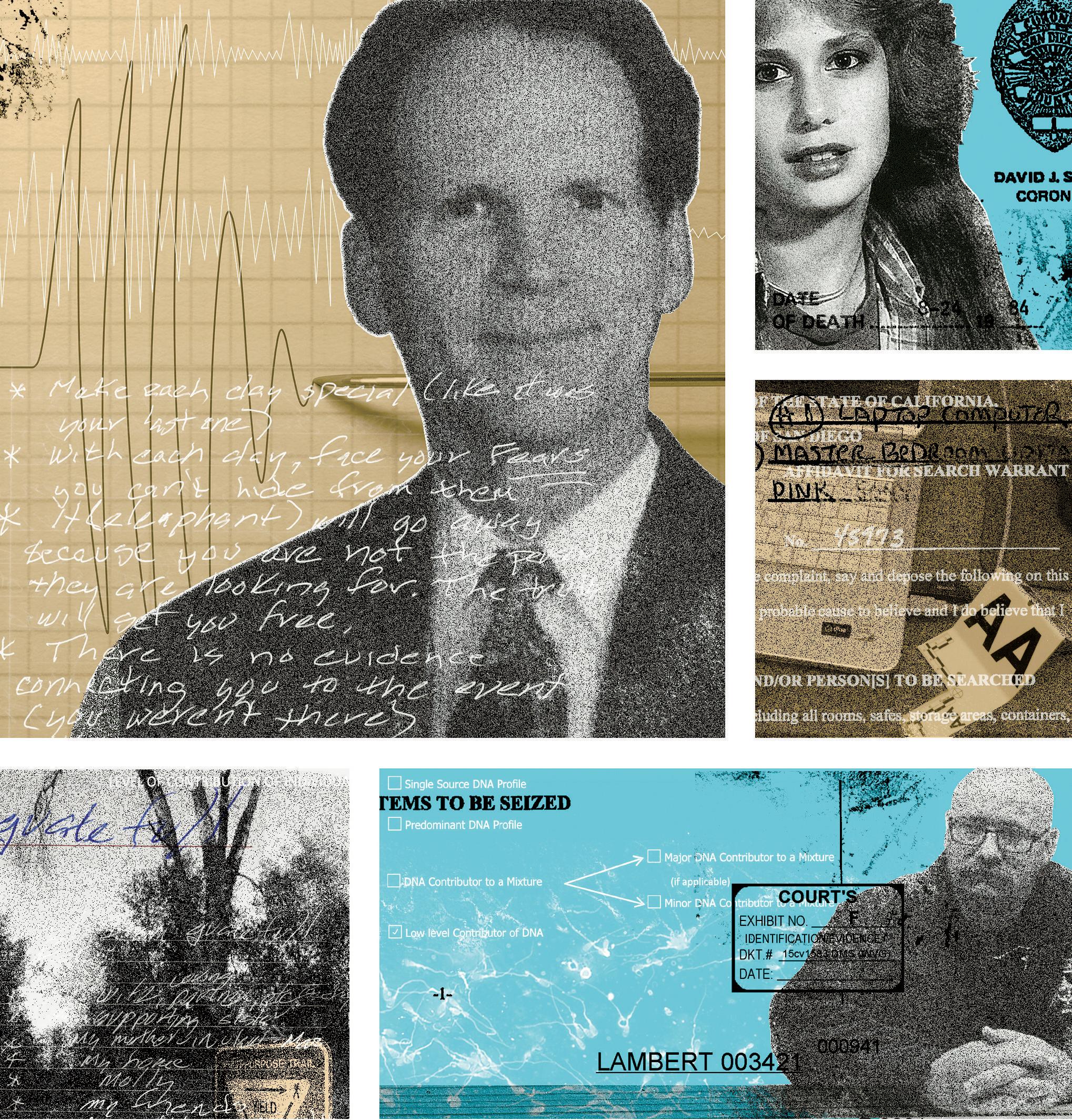

TOP, clockwise from upper right:

Murder victim Claire Hough and a portion of the autopsy report.

A laptop photographed by San Diego Police during a search of the Brown home with parts of a handwritten inventory list and the search warrant.

Detective Lambert with portions of a search warrant and an SDPD Forensics Quality Incident report.

Cuyamaca Rancho State Park with writing from Kevin Brown’s journal.

Kevin Brown with his journal and a depiction of a lie detector test.

Brown: “I don’t know what to say It wasn’t me. I don’t know how my sperm got in her and I didn’t do that.”

Afew minutes later his mother-in-law walked in. She lived in the house and had overheard something “This sounds serious, she said.

“Yeah,” Brown said “Would you get John? Call John.”

John is John Blakely Brown’s brother-in-law. He lived in the house, too. He’s a defense attorney

The interrogation was over

But the detectives weren’t finished. They handed Brown a search warrant they had obtained a few days earlier More than a dozen officers came in and began removing things and taking photographs. They were there for several hours.

The warrant authorized them to take computers, cellphones, diaries photos, newspaper clippings videos items that detectives thought might show Brown and Tatro had been in communication over the years since the murder or that Brown had been following media accounts of the Hough case, or that he had an interest in sadomasochism

When they were done, they carted away 14 boxes, a suitcase and four trash bags thousands of objects, many with little obvious connection to the case. They took cookbooks, a Bible, a copy of the Declaration of Independence, asigned photo of former President George H.W. Bush.

It would be up to the detectives to sort through it. But first they went to Mater Dei Catholic High School, where Brown’s wife, Rebecca, taught. They explained what was going on and asked her to drive home so her car could be searched, too.

Standing in the school parking lot, Adams would later recall, she heard Rebecca Brown mutter this: “Boy, I sure know how to pick ‘em.”

Later that day Kevin Brown left a message for the detectives. He wanted to talk some more. This was unusual.

“I don’t think I ever had a suspect ask me back before,” Adams said, “especially into their house.

When they met the next morning, Brown said he’d been thinking, “trying to piece in my memory what might have happened in my life, and the name Claire kept popping up.”

He remembered an episode with a friend named Mike, “a hustler who liked to go out and meet women Brown couldn’t pinpoint when it happened, but he thought it might have been around the time Hough was murdered, almost 30 years earlier “Mike met these two girls,” Brown said, “and I believe one of