3 minute read

Going beyond pop art

Wayne Thiebaud was often lumped in with Warhol and Lichtenstein, but his deceptively smart work asked you to look closer

BY PHILIP KENNICOTT

Advertisement

His paintings were instantly recognizable, and no serious museum of contemporary art was complete without at least one hanging on its walls Wayne Thiebaud, who died on Christmas Day at 101, painted sweets, clowns and bow ties and somehow managed to capture the essence of his era in work that was deceptively smart, wry and engaging.

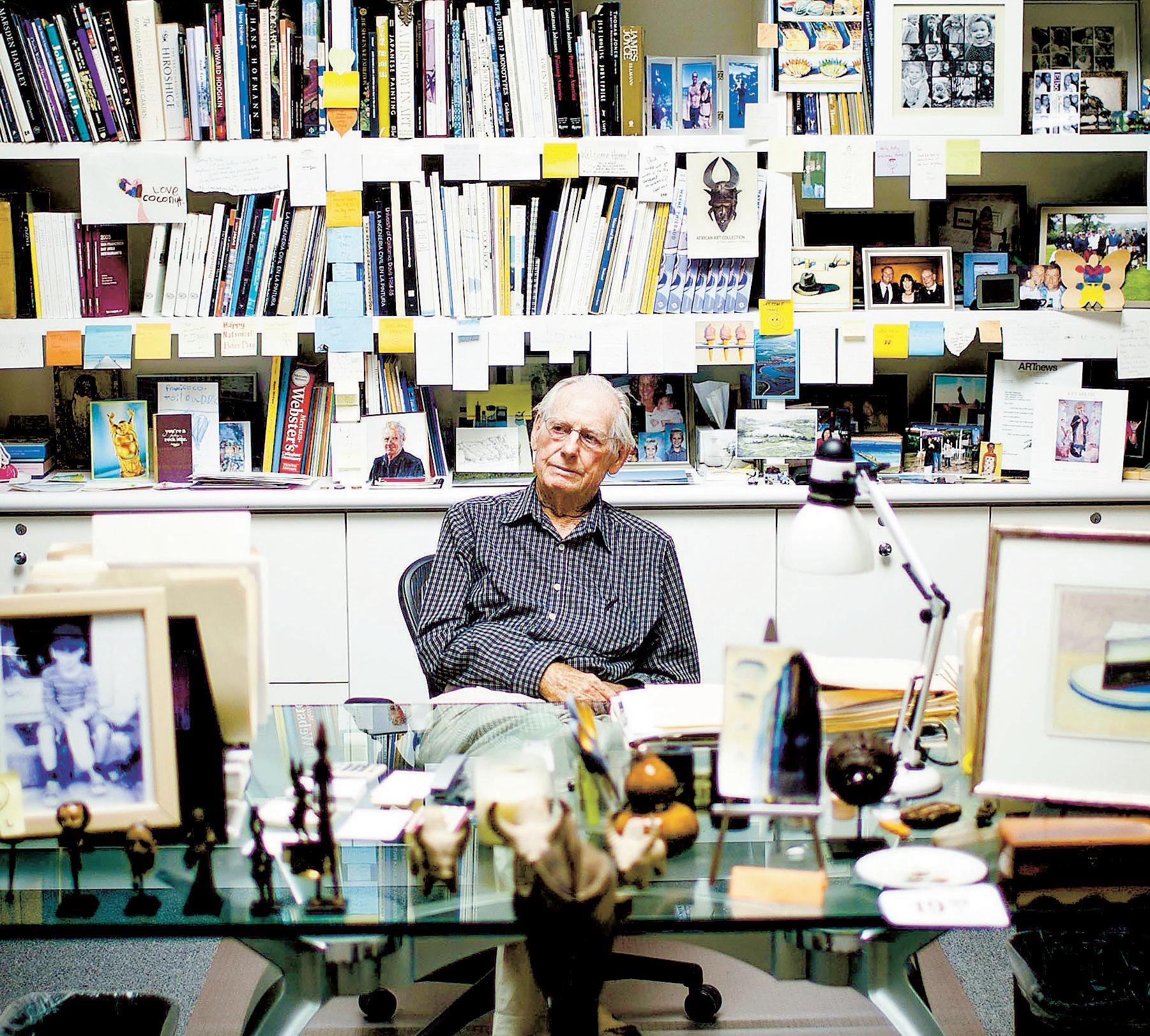

Thiebaud remained productive into the last years of his life. He was still doing interviews slightly more than a year ago, when an exhibition to honor his 100th birthday opened at the Crocker Museum in Sacramento. He was still painting, still observing the world, still making work that seemed to glow the way the skin does after a day in the sun, as if from a surfeit of light.

He was already making art in high school and spent a summer as an animation apprentice at the Walt Disney studios He was a masterful draftsman, and his early experience with commercial art helped govern his eye, and his hand. Even as he pushed familiar objects to the point of abstraction, isolating them from the world and arranging them with geometric lucidity, he was meticulous about shadows, reflected light and texture Art museums always seem to favor his lunch-counter images, the pies and cakes. Thus, the institutions that collected his art made those works his signature pieces. But he was also an accomplished and powerful portraitist, and his landscapes, made in dialogue with those of his fellow California painter Richard Diebenkorn, are among his finest achievements.

Museums often feed our inclination to not look at things. We enter a gallery, register the familiar icons, situate them in our mental map of the art world and move on.

There’s a Warhol, there’s a Lichtenstein, there’s a Thiebaud. His work was routinely grouped with that of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and thus he must have been a pop artist. But his art resisted the inclination not to look with marvelous energy And as you were drawn in by its power, waylaid into actually seeing it, the more it seemed a world apart from pop art.

The tone was different, not quite so satirical or arch He gravitated to consumerist images, things that were familiar enough that they left room for the painter to translate them into something else. Yet the paintings never gave the viewer permission to condescend to the subject matter. There was, no doubt, a critique of American consumerism somewhere in them, but that wasn’t the thrust of what they were meant to do. There was always an admixture of delight, which tempered any inclination to be sniffish about the Americana that Thiebaud painted.

When asked about the work that came to define him, he stres- sed instead his desire for maximal freedom as a painter Painting was apassion, a calling perhaps even an obsession. Even if he gravitated back to familiar objects, in a distinctive palette of pastel colors and rich blue shadows, it was the dialogue with art that mattered.

“For me, making a good painting, or a special painting, is probably one of the great achievements of mankind,” he said a year ago November “It is on the level with scientific research, so my feeling is, once you enter that community of painting which is a sort of secret society dependent on art history you want to compete, you want to contend, however small, or however inadequate.”

Among his imagery were eyeglasses which, along with mirrors and frames and other devices that foreground our ocular relation to the world, focus on the idea of looking And not just looking, but the flawed imperfect, subjective nature of looking. We need art because we are not particularly good at looking at the world. We see things all the time, yet when some truth finally registers in the mind, we say, “I see,” as if our eyes were closed before this epiphany

In a 1992 painting, “Untitled (Row of Glasses),” Thiebaud arranged eyeglasses on a thickly painted white plane as if someone had frosted a table with cream cheese and then pressed the spectacles into the goop. The angle of vision and the recession of the perspective skews the ones in the farthest row so much that they would be unrecognizable if the ones in the foreground weren’t so expertly rendered. We can for a moment, see ourselves seeing, taking in the image in a glance, while also registering how we tend to see from one thing to another, unconsciously connecting things, fabricating a vision of the world from chains of otherwise meaningless data. There may also be a sleight of hand with time: Are the glasses nearest us the oldest, while the ones in distance are more of our moment? Is the past easier to read than the present?

It’s curious to see so many eyeglasses in one place. Perhaps we are meant to think of a shop where glasses are sold. Or perhaps someone with a slightly obsessional relationship to things has kept all of his or her glasses over the years and arranged them like pictures from a family album on the table. Perhaps the artist is saying something else. He has through his painting, made these objects obsolete. As people look at his art, they take their glasses off, and leave them behind, as some people do with crutches, splints and bandages after visiting a healing shrine.

We have touched that secret society that Thiebaud aspired to and can say: I see.

Kennicott is the art and architecture critic for The Washington Post.