5 minute read

A gift for the future

SWI FOUNDER CATHERINE BLAIR’S FAMILY SUPPORT THE HERITAGE PROJECT

When Scottish Women’s Rural Institutes (SWRI) was founded in 1917, it was the brainchild of a formidable woman and ardent suffragette, Catherine Blair.

Now, more than a century on, Catherine’s family has been inspired by the SWI’s plans to protect its heritage and has donated a precious family heirloom to the organisation.

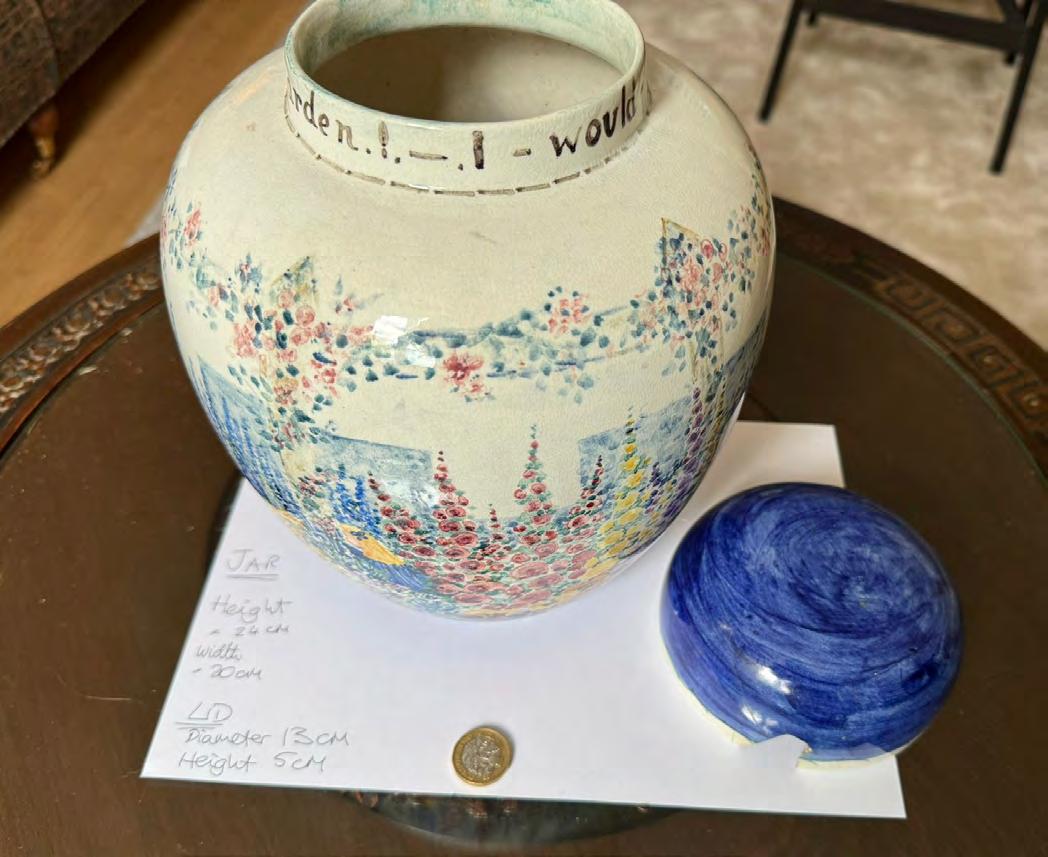

Catherine’s great-granddaughters, Mairead, Catriona, and Morag have gifted a ginger jar hand painted by Catherine. It depicts her two daughters dancing in the garden and will become a centrepiece for the Visitor Learning Centre currently being planned on The Crichton Estate in Dumfries. This will help tell the story of this innovative and formidable woman.

A busy farmer’s wife, Catherine was a champion of women’s rights and throughout her life she was a strong voice for rural women in particular.

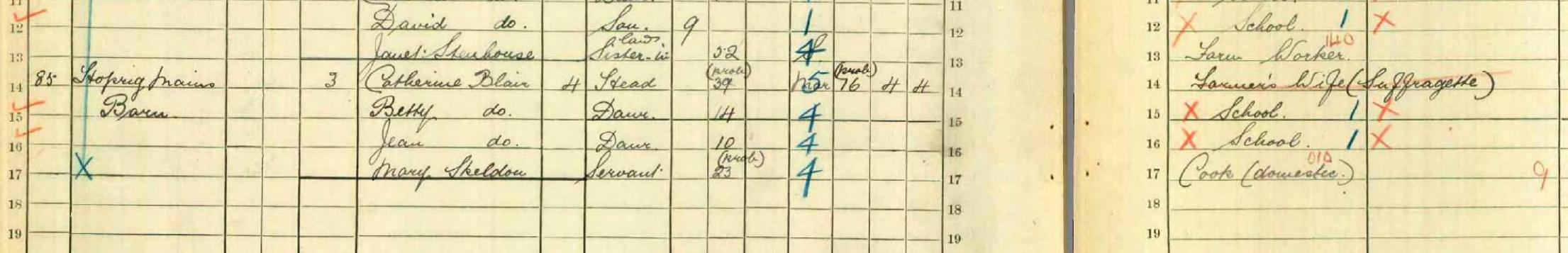

As the campaign for women’s right to vote was in full swing, Catherine moved into the barn with her two daughters and a maid. This was just before the 1911 census, and meant she would be counted as a head of house in her own right.

Before the First World War her home at Hoprig Mains, East Lothian, became a safe haven for suffragettes. Initially, women who passed the farm on the long walk down to London were given tea. However, by 1913, Catherine was sheltering suffragettes in her barn.

Catherine was a woman of means, but also a champion of the ordinary Cottar woman. It was a dairy maid’s passing comment that she had no one to talk to which spurred her on to help isolated women in rural communities.

When she heard of the new Women’s Institutes being established in Canada and England she was inspired to launch the first Scottish Women’s Rural Institute in Longniddry.

Catherine saw the benefits that such craft skills could have on women's independence. The idea was that it would enable rural women to meet up with others to ease loneliness and learn new skills such as painting or embroidery which could help them earn them an income of their own.

Catherine’s actions led to the biggest women’s movement in Scotland with more than 50,000 members around the country.

In 1919, shortly after the first Rural was formed, Catherine gave a pottery painting demonstration which led to members of the Rural decorating blank pots, known as biscuit ware. However, as time went on, Catherine established the Mak’Merry studio in a garden outbuilding on her farm. Catherine called herself the Heid Painter and was assisted was Betty Wight, a daughter of the grieve at Hoprig Mains.

Mak’Merry Pottery was then established in 1920 as a trading arm of the SWRI. Using pottery as vehicle for artistic expression, Catherine gave lonely and isolated country women an opportunity to socialise, make money of their own and be less reliant on their husbands sharing money.

Initially, members invested small sums of money and produced food items for sale –but they soon moved into producing fine crafts, one of which was pottery decoration.

The Mak’Merry studio became a commercial business. Pots were bought in from areas such as Bo’ness and Kirkcaldy and decorated. By 1932 its success was such that ‘Mak’Merry’ pottery was registered as a trade mark. Much of the decoration was inspired by the local area with fruit and flowers a common theme. However, inspiration was also drawn from the designs being developed at the Bough studio in Edinburgh. Mak’Merry pieces were frequently highly coloured using blue, yellow, red, green and turquoise.

Popular at home, Mak’Merry also developed an overseas market in the likes of Canada, Egypt, and the USA.

During the years, pottery painting classes were organised in various Rural Institutes. Items were sold at the Highland Shows and bought by Queen Mary and the late Queen Mother.

Top: The 1911 census shows Catherine Blair’s occupation as a suffragette. Above: The ginger jar will take pride of place in the Visitor Learning Centre

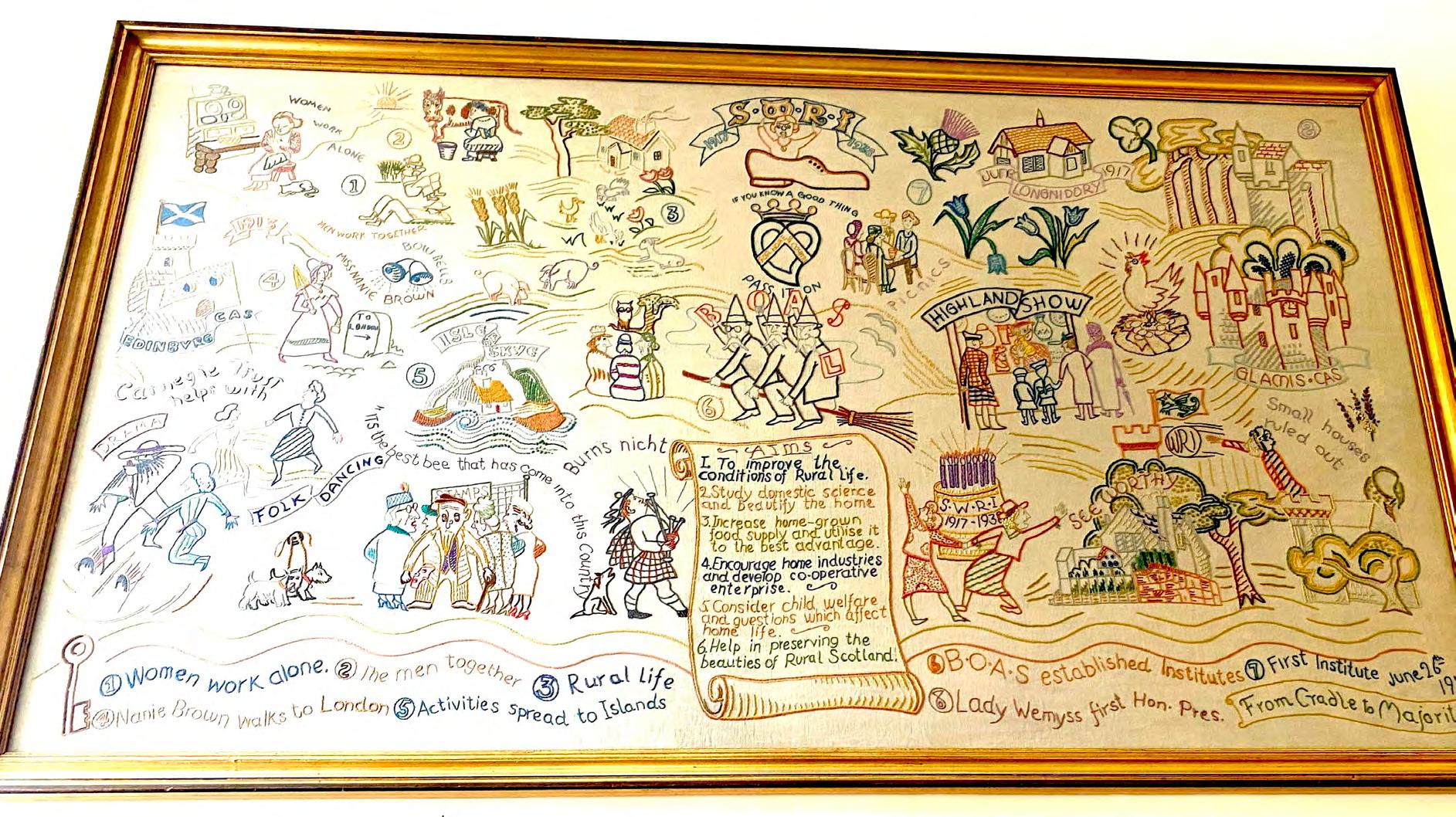

Adapting suffragette slogans and adding her own telling phrases, Catherine produced items with slogans such as ’Deeds Not Words’, ’For Home and Country’ and SWI’s motto: ’If you know a good thing pass it on’, most items are now in museum collections. However, few displays tell of the enormous social history they hold. They symbolise a tumultuous period of change in rural Scotland.

Because of Catherine Blair’s vision, women went on to take up governance roles, become an army of helpers throughout World War II, and work with government departments to upskill women in matters such as hygiene in the home, growing food and providing for others. All while bettering their own lives.

Find out more about the SWI Heritage Project at www.theswi.org.uk/heritage

A huge embroidered panel which tells the story of the origins of the SWI is a key part of the SWI collection. It features the organisation’s aims and the mantra ‘from cradle to majority’ across its 1.5m wide canvas.