7 minute read

Hosea Williams as a Founding Father of A Better America

By: Rolundus R. Rice

The Rev. Hosea Williams is an anomalous figure who is both known and unknown in the historiography of the Black freedom struggle. I was perplexed when I approached the prospect of writing my dissertation on Williams as a Ph.D. student at Auburn University to my adviser. Dr. David Carter. Carter and I plowed through hundreds of books in the historiography of the civil rights movement to confirm our initial observations about the lack of ink that scholars had devoted to the fiery and bombastic agitator from Attapulgus, Georgia. Historians had relegated Hosea Williams to a few paragraphs or to a footnote to the pages of what had been otherwise solid treatments that examined civil rights agitation in the United States post the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954. Some of the most celebrated historians of the period have chosen to give only scant and fragmentary attention to Williams’ contributions to civil rights before and beyond his fifteen-career with the local Savannah affiliate and national Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) from 1963-1979, and no author, prior to this writing, had attempted a scholarly biographical treatment of his life.

A few scholars and some of Williams’s contemporaries recognized the old warhorse’s contributions to the Black freedom struggle. According to David Garrow, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, “in the 1964-1965 timeframe, Hosea was as valuable as anyone in SCLC to Dr. King because of his courage and willingness to lead dangerous demonstrations…People may remember Andy Young and John Lewis, but…Hosea was just as important to the movement.” John Lewis, a founder of SNCC who participated in the Freedom Rides and marched shoulder-to-shoulder with Williams on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday,” called the fiery activist an authentic hero. ‘’Hosea Williams must be looked upon as one of the founding fathers of the new America,’’ he said. ‘’Through his actions, he helped liberate all of us.’’ Joseph Lowery, a founder of the SCLC and Williams’ former boss who fired him as Executive Director of the SCLC in 1979, portrayed the old warhorse of the movement as fearless. ‘’Hosea wasn’t afraid of Goliath,’’ he said. ‘’In fact, I was thinking about it, and I don’t think there anything he was scared of.’’ He said Williams tackled ‘’the Goliaths of greed and indifference’’ that created a permanent underclass. Williams has been portrayed as courageous, fearless, and integral to the modern Civil Rights Movement. However, few scholars stopped shy of recognized that Williams was actively

engaged in civil and voting rights activism prior to meeting King and his subsequent fulltime employment with the SCLC. None have lionized him in the same way as some of the aforementioned iconic activists despite the evidence that supports the argument presented here that Williams justly deserves to be recognized as a first-ballot Founding Father of a newer, better America. Lewis, Lowery and Vivian, towering timbers who fell during the last three years, were all awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by Barack Obama—the first President of the United States of African descent whose initial ballot for the nation’s highest office was cast on a bridge named for a Confederate general on a cool day in March, 1965. It is time for Williams to posthumously receive the nation’s highest civilian honor.

The rich documentary trail of evidence that spans more than forty years of Williams’s activism supports the claim above. He was one of the principal leaders of the campaign that led to the desegregation of public accommodations in Savannah, Georgia, prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Dubbed as “Atlanta’s eternal marcher” in a column in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Williams, at age 61, was still galvanizing marchers, approximately 20,000, in Forsyth County, Georgia, in 1987. Both sustained protests altered both Deep South cities. A deeper exploration of hundreds of additional civil rights campaigns remain beyond the scope of this article. However, the Hosea-led march that pushed President Lyndon B. Johnson to proclaim before a join session of Congress eight days after the melee on the Edmund Pettus Bridge merits quotation: “At times, history and fate meet at a single time in a single place to shape a turning point in man’s unending search for freedom. So it was at Lexington and Concord. So it was a century ago at Appomattox. So it was last week in Selma, Alabama.” Presidential utterances are consequential. Johnson had strategically compared, and rightfully so, “Bloody Sunday,” to battles that ignited the American Revolutionary War, and the binding together of the northern and southern states that had been torn asunder over the issue of slavery. The principal actors in both sagas, George Washington and Ulysses S. Grant, later ascended to the presidency and were eventually immortalized by monuments and currency. Williams has a 3.3 mile street named in his honor in the district he represented as a member of the Georgia’s General Assembly from 1974-1983. Selma, a seminal campaign of the movement, canonized one American, and cannibalized another.

The events surrounding the organizing and planning of the initial march to Montgomery from Selma in 1965 have never been shrouded in mystery or the subject of serious debate among scholars and participants in “Bloody Sunday.” SCLC president, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., issued a firm directive to Williams to not proceed with the protest on the morning of March 7. “Call the march off today, Hosea,” said King. Williams refused. “No. Doc, I can’t support you,” Williams, the insubordinate, but loyal lieutenant said to a stunned King. King deploys Andrew Young to Alabama via airplane to postpone the march until the following day. From the safety of retrospect, any observer could understand the practical reasons why King did not believe that Williams’s plan to lead several hundred nonviolent marchers on a 54-mile trek from Montgomery to Selma without the necessary provisions was ill-conceived. Williams, SCLC director of voter registration and political education, did not relent. He continually pulled from his arsenal of agitation to motivate protesters to join the march.

“I just really went wild in that pulpit…people were jumping all upside the wall,” recalled Williams. The documented chronology of the events has not changed in nearly fifty-six years. Marchers were beaten by Alabama State Troopers. The video and photographic footage was seared into the minds and memories of those who watched these images during ABC’s interruption of “Judgment at Nuremberg” later that evening. The public sentiment toward equal access to the ballot seem to have changed because of the march that resulted from one’ man’s defiance of another sainted civil rights leader. The Voting Rights Act of 1965, a measure that outlawed a range of ingenious legal tactics that prohibited Black citizens from participating in the political process, was signed into law only five months after the Selmato-Montgomery March.

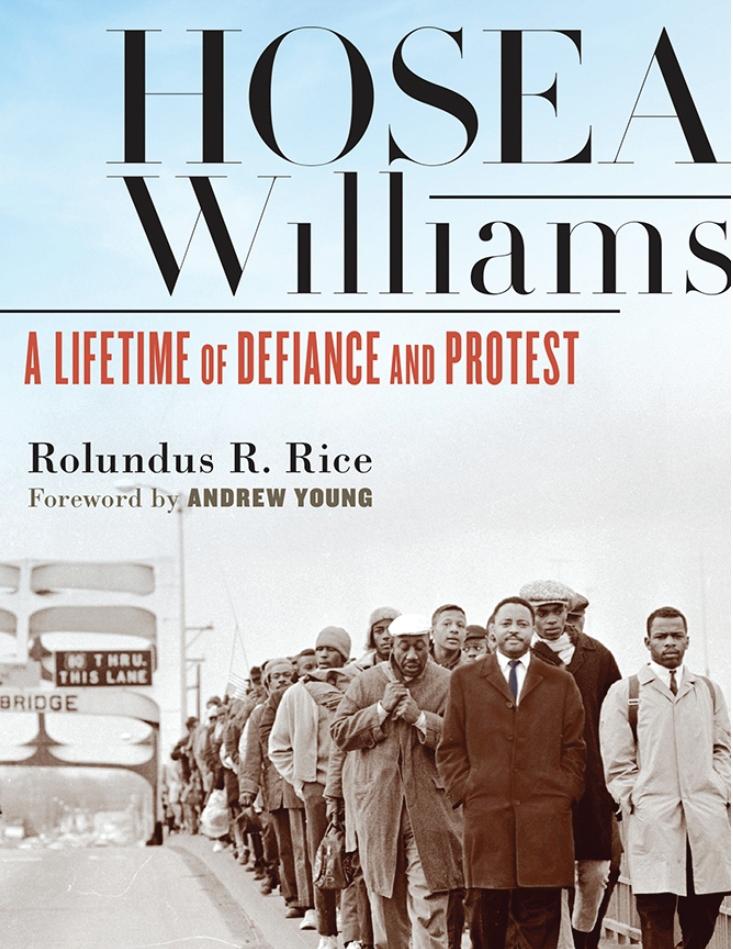

My recent book, Hosea Williams: A Lifetime of Defiance and Protest, published by the University of South Carolina Press can be purchased in all major bookstores. The manuscript covers the Selma campaign and is separated into ten chapters that chronicle Williams’s complicated life from the year he was born to blind parents in 1926, until his passing in 2000 at age 74. My thesis is straightforward and matter-of-fact: Hosea Williams was of central importance to the most successful nonviolent revolution for freedom and equality in world history. He was bombastic, belligerent, barrel-chested and baritone – all of which he used in his arsenal of agitation. Williams was also imperfect. His decisions behind the wheel of his Cadillacs befuddled observers and somehow unjustly recast him into a caricature. He was also diagnosed with sleep apnea and suffered from chronic pain due to the beatings he endured at the hands of gangs of white civilian mobs and law enforcement. He does not deserve a proverbial pass for his misdeeds. However, his hall of fame stat sheet, which includes more than 130 arrests; three civil rights acts that he influenced as an activist and strategist; documented protests at age 72 as a cancer patient and more than one million free meals doled out to Atlanta’s forlorn and forgotten, merit maximum feasible leniency when judging his legacy. One is left to wonder how Hosea Williams might have been portrayed if he had a chauffeur.

T H E I N T E R N A T I O N A L B R O T H E R H O O D O F T E A M S T E R S

On the Occasion of Black History Month

JAMES P. HOFFA General President

KEN HALL General Secretary-Treasurer Rolundus Rice is Ph.D Provost & Vice President for Academic Affairs at Rust College