1 minute read

Shedding light on bat behaviour

Energy Saving Schemes Such As Partial Night Lighting Can Pose A Risk To Some Wildlife

BY: RIA GRIFFITHS

Advertisement

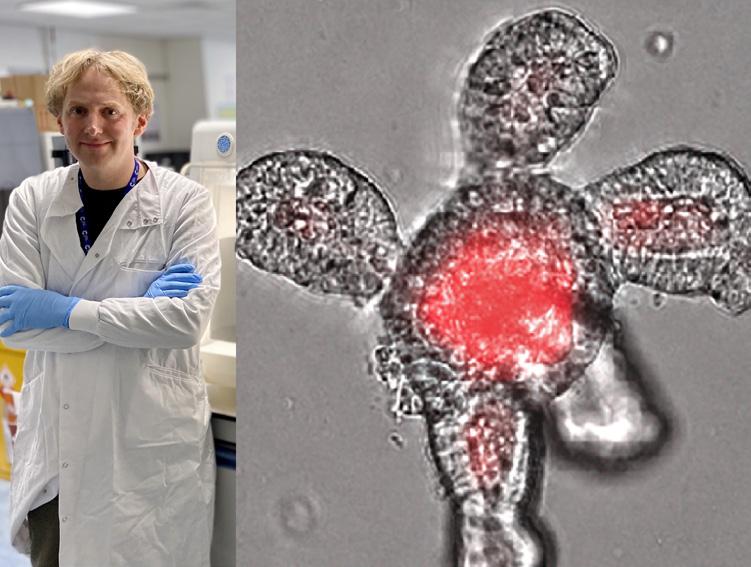

The biodiversity crisis caused by artificial light cannot be solved with the flick of a switch. In fact efforts by local authorities to save carbon and cost through lighting reduction schemes can actually pose a risk to nocturnal wildlife. Research into waterways which are only partially lit shows a reduction in feeding and activity levels in certain species of bat. As bats are a strong bioindicator of the health of an ecosystem, these insights can tell us how conversation measures, such as reduced lighting, impact the immediate environment. PhD student Jack Hooker has worked as ecological consultant specialising in bat mitigation and is familiar with the challenges of human-wildlife conflicts. He is currently researching the impact on bats when habitats are temporary disrupted due to human activity and how well mitigation measures work. With public health measures in place for COVID-19, Jack had to adapt his research. He began a smaller, connected project to examine light reduction schemes on waterways and their impact on bat behaviour. Focusing on eight unconnected waterways, lighting experiments were conducted over a period of four nights. With one night in complete darkness, the other nights were lit for varying periods of time: 2 hours, 4 hours or the full night. Expecting that bat activity would drastically reduce with the introduction of any lighting, Jack was surprised when they continued to fly through, “The bats obviously had predefined routes or roosts in proximity to the study area and they were trying to either forage in that area or get to another area to forage.” Whilst the bats were still there, feeding rates either dropped off or were pushed back in accordance with the lighting times, with bats missing the peak time for insects. This project highlights the complexity that comes from a need to simultaneously tackle climate change, protect biodiversity and minimise disruption to human activity. In this instance whilst reduced lighting may help climate change, the impact on the local bat population was less favourable. When it comes to these often competing challenges, Jack’s objective is to provide an evidence base to enable organisations to make sound decisions about the ways to alleviate the impact of human activity. “There’s always going to be a need for lighting, so is there a way where it produces minimal disruption to humans, but increases the benefits to nocturnal wildlife?”

According to Jack there are things we can do individually to help alleviate the impact on bats from artificial light, as well as support in their well-being more generally. Turning off large lights in our gardens, putting up bat boxes and planting night-flowering flora can all make a SM