4 minute read

Pleasanton Unified School District tells a story.

by SchoolCEO

When Pleasanton Unified School District in California went out for their 2022 bond, the stakes were high. Their last bond—which had come to a vote in March 2020—had failed in the wake of a mounting global pandemic. In fact, over the previous 25 years, the district had only passed one bond.

When votes started coming in on Election Day, it looked like Pleasanton USD was set to continue its streak of failures. But over the next two weeks, as mail-in ballots were counted, the district pulled up from behind and clinched a victory.

Advertisement

“We had a stomachache for a couple of weeks,” says Superintendent Dr. David Haglund, “but I was confident it would end up passing—and it did.” Looking at the voting bloc, only 27% of voters had a child in the district, meaning Pleasanton USD’s success was truly a community effort. So how did they get so many people on board? They told a good story.

Good stories are honest.

Schools are cornerstones of their communities, and as a school leader, it’s natural to want your stakeholders to take pride in their local district. It can be hard to admit when things aren’t exactly going perfectly—but sometimes it’s necessary. “The community here isn’t used to being told they’re not as good as the community down the road,” Haglund explains. “They’re used to thinking of themselves as the better place.” But in reality, Pleasanton USD’s facilities badly needed renovation. “The theater’s back corner was sinking. The basement was flooding,” Haglund tells us. “One of the high school gyms was 50 years old, and the other was 100 years old. They didn’t have heating or air conditioning.”

So the district told the truth about their needs. Not only did Haglund and his team give tours of the campuses, but they also held town hall meetings inside the schools and did virtual walking tours for people who couldn’t visit in person. “I think once people actually started touring the facilities and realizing what was really there, some folks were kind of embarrassed,” he says. “We showed them the rotting beams on the roofs, the cracks in the bricks, the ugly parts. That’s not easy to do, but if you don’t do it, you’ll never convince people of the need.”

Good stories build into a broader legacy.

Throughout the campaign, Haglund and his team found themselves coming back to the idea of building a legacy. “We constructed a lot of our narrative around that idea,” Haglund says. For example, Bill Butler, one of two parents who spearheaded the local advocacy group, is a former basketball coach. For him, leaving a legacy meant improving that 100-year-old gym. “When it’s 37 degrees outside, it’s 38 degrees in the gym,” explains Haglund. “They have jackets on trying to practice basketball, and that made Bill embarrassed. That wasn’t the image of the community that he wanted to raise his kids in. He knew he couldn’t just sit back. That’s the story he tells.”

Haglund goes on to describe other members of the community who have stories similar to Butler’s, who couldn’t help but want to make a difference for future generations of students. “I don’t know that anybody said: Hey, let’s talk about our legacy ,” Haglund explains. “It just rose out of conversations with people in the community and stuck. It was just a natural part of the storytelling.”

Good stories appeal to a wide audience.

Since fewer than 30% of Pleasanton USD’s voters had children in the district, their bond campaign had to appeal to everyone—even voters who didn’t feel they had much to gain from a new high school auditorium. “One of the pieces of the narrative that I had to create for the community was that these are not just school facilities,” Haglund tells us. “Every single one of these buildings is accessible to the community when school’s not in session. Plus, good school facilities create better property values, which create great resale values.” The reality is that better school facilities benefit everyone.

Convincing the community of that fact also meant combatting a growing “us versus them” mentality. Parents and families of older students and alumni weren’t immediately seeing the state of the district as their responsibility. There were also members of the community looking for someone to blame. “They were thinking: We did our part. Now, it’s their turn to take care of the schools ,” says Haglund. “So the line I came up with is: None of this is my fault, but it’s all my responsibility .” By inviting the whole community to take collective ownership over the district’s shared legacy, Haglund and his team made sure voters would turn up on Election Day— whether they had students in the district or not.

Make sure your story is heard.

Haglund and his team did everything they could to share their message. The district and the advocacy campaign worked together to give presentations throughout the community. “I’d give my talk about need,” Haglund says. “Then, I’d leave the building, and the advocacy campaign chairs would pump everyone up and explain how to volunteer.”

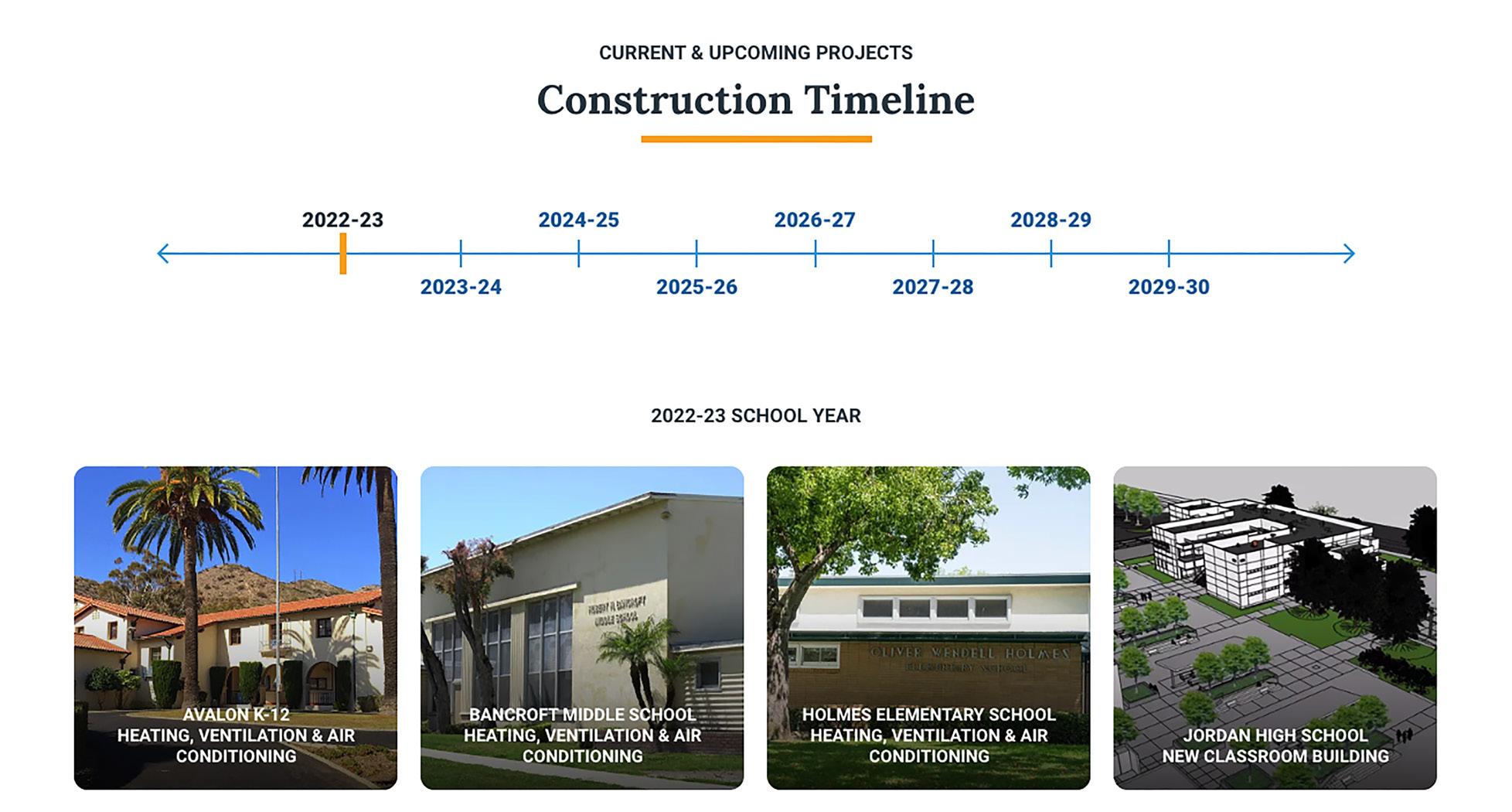

The campaign leaders also recruited folks to write letters to the editor about voting “Yes”—which often prompted the newspapers and magazines to contact the district for more info. Pleasanton USD also hired architects to generate mockups of the proposed projects to help their community visualize their potential future. “In a book, the pictures are part of the story,” Haglund explains. “In some cases, they’re even more important than the narrative.”

As Haglund says, “Storytelling isn’t just about bonds; it’s about the work in general.” It’s this key insight that helped the Pleasanton team garner community support for the 2022 bond. But it wasn’t easy. Passing a bond is hard work, and, according to Haglund, “if you’re going to take on a project that’s hard, then you have to tell a story that will motivate people.”