2 minute read

MYSTERY OF THE FLOWER BEETLES

In late summer’s heat, wildlife can be hard to spot. Yet while passing through an arid landscape, you may observe Schlinger Chair and Curator of Entomology

Matthew L. Gimmel, Ph.D., and his wife, Scientific Imaging Specialist Lucie Gimmel. Matt beats bushes and collects falling beetles in a pan; Lucie—whose background is in botany—documents the plants. The Gimmels are after flower beetles in the subfamily Dasytinae (daz-ee-TEEN-ee). This symbiotically scientific couple do much of their fieldwork in July and August, when particular adult dasytines (DAZ-ee-tines) are active.

Advertisement

Studied over a century ago in a piecemeal fashion, the dasytines have been neglected—until now. Despite the adult beetles’ great abundance, scientists don’t know much about dasytines’ early lives. The appearance and whereabouts of their larvae are generally unknown. Dr. Gimmel and collaborators are trying to make sense of this diverse group of small, subtle insects. With Adriean Mayor, Ph.D., of University of Tennessee, Gimmel plans to sort out who’s who and pave the way for further study.

The coauthors are loading up their publications with details gleaned from research and collecting, including data about plants. “That’s a special twist that we enjoy adding to this work,” says Gimmel, who has benefited from plant associations recorded by others. Dasytines are often found on shrubby perennials like California Buckwheat. “The annuals they are attracted to tend to be ones they can hide in,” Gimmel explains: late-blooming plants with flowers that provide tiny beetles with a safe, moistureconserving cubicle.

In a recent publication, Gimmel and Mayor sorted out a tangle of related dasytines. They transferred two beetles into a new genus, determined that seven previously-named species are actually a single one, restored the status of a species named in 1895, and described two new species. The third in a series, this paper was just a step in an expansive program of dasytine publications they have long planned.

“This paper is coming full circle,” says Gimmel. Soon after he came to Santa Barbara in 2015, he and Mayor collected a flower beetle with unusually long black hairs. At that time, the two were just getting drawn into dasytine mysteries. The specimens that started off Gimmel’s collecting career in California are now finally described as Microasydates santabarbara.

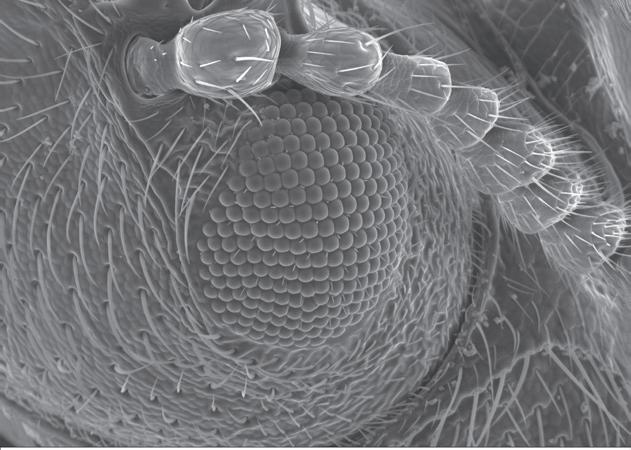

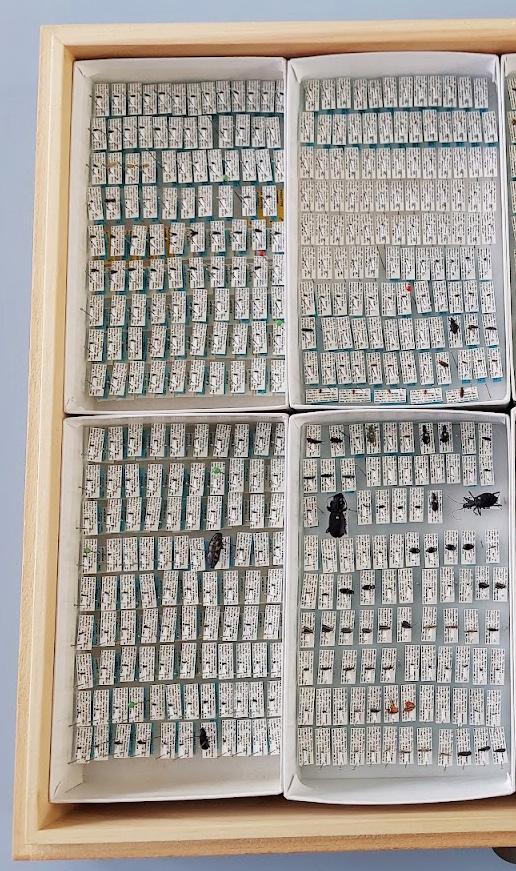

Late-summer collecting is key to the process of bringing order to chaos. When it comes to insects, fresh specimens are better for dissection to spot the physical distinctions between species. Experts like Gimmel and Mayor are attuned to differences in the shapes and configuration of wing covers, reproductive organs, and setae (SEE-tee, insect fur). Their obsession is growing our collections, as thousands of these beetles are painstakingly mounted, labeled, and made digitally searchable. It’s fitting that Dasytinae should be an area of strength here; California is a dasytine hotspot, home to about 200 of roughly 300 species known in North America.

Further reading: Gimmel and Mayor, “Revision of Microasydates, New Nearctic Genus of Soft-Winged Flower Beetles” in The Coleopterists Bulletin 76(4), December 2022.