22 minute read

Frank A Pettis

Reedsburg’s Civil War Drummer Boy

William C. Schuette

©2016,2021

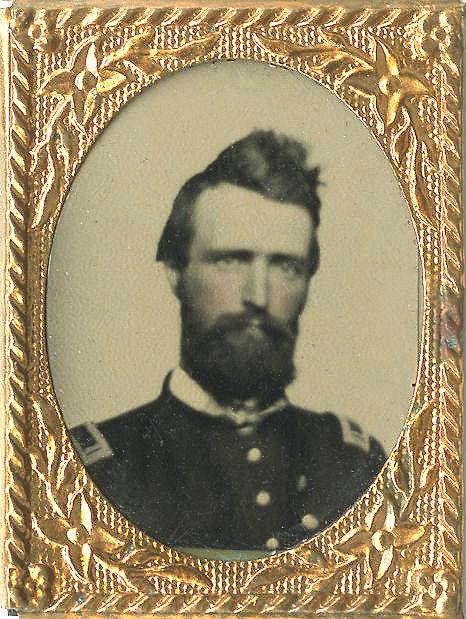

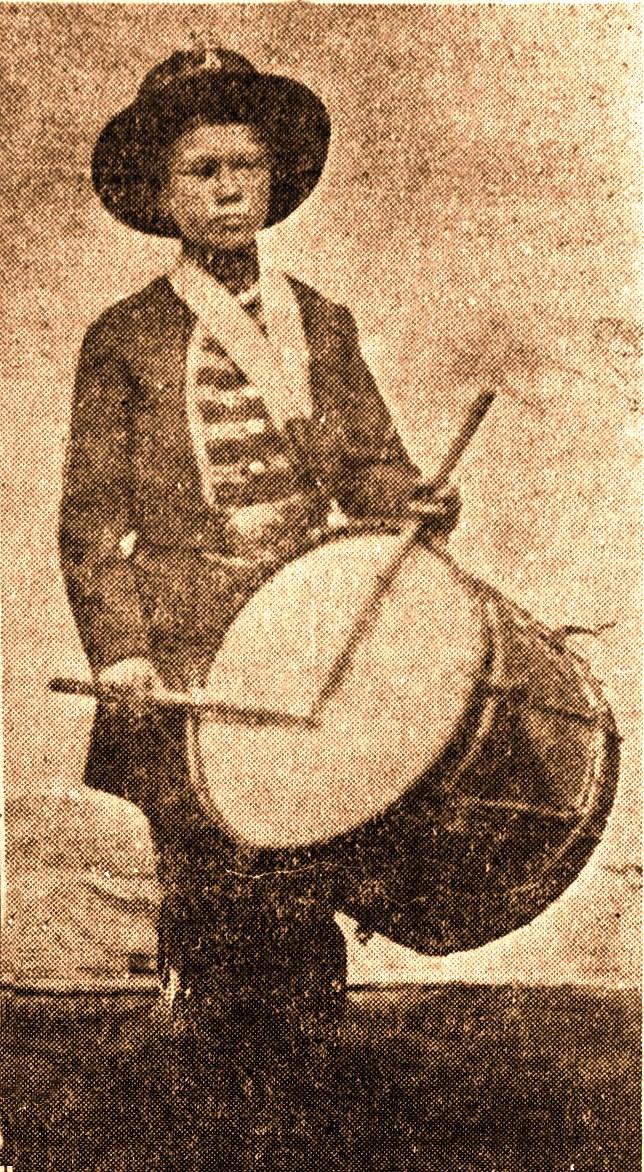

FrankA. Pettis

Age 11 or 12

This is the story of an eleven year old Reedsburg boy, who in 1862, enlisted in the Union Army as a drummer. Along with his father, Amos, and his teacher, A.P. Ellenwood, they volunteered to help fight the rebels during the American Civil War. Many thought the war would be over in a few months…..It wasn’t.

Frank Pettis* was born in Cranesville, Erie Co., Pa. January 22, 1850. When he was about three years old, he moved to Reedsburg, Sauk County, Wisconsin, with his parents, Amos Pettis, and Cordila, nee Cole. At the time Reedsburg was just a small village located along the Baraboo River.

Upon entering school, Frank was taught by Alexander P. Ellenwood, also an early settler in the village.

Ellenwood came to Reedsburg in 1858, and taught school there for one year. In 1859, he became principal of the Reedsburg Union School until 1861. It was noted that Ellenwood, “Being of a patriotic disposition, loving his country and his flag, he felt it to be his duty to give his services and life if need be, for them.” He enlisted in the 19th Regiment, Company A, Wisconsin Infantry as a lieutenant at the beginning of the Civil War, and rose to the rank of Captain. When he left for the war, several of his stu- dents went with him.

*The family name was spelled several different ways: Pettyes, Pettys, and Pettis. These spellings are used interchangeably in this biography, usually depending upon how it was recorded in the historic records.

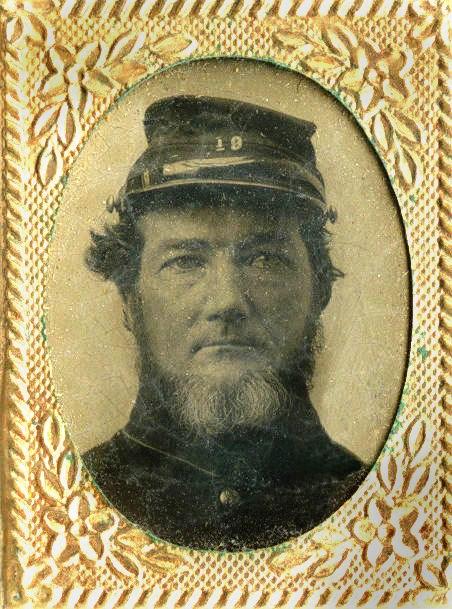

Amos Pettis (or Pettyes)

was born May 4, 1816, in New York state, to Israel Pettyes and his wife. Amos was married twice: first to Cordelia A. Cole (1821-1862) and then in 1865, to Margaret A. Devy Pomeroy Miller (1827-1905). Amos and Cordelia were the parents of Louisa Pettyes (1843-?), Electa P.(Pettyes) Worden (18441930), Frank A. Pettis (18501918), and Fred E. Pettyes.

Amos Pettis

When Amos married Margaret in 1865, the widow of Dr. Ekanah Phelps Miller who died in Iowa, she brought to the family her three children, Elizabeth Miller (1857-?), James Miller (1859-?), and Fred Miller (1866-?). Their marriage took place in Columbia Co., WI.

When the Civil War broke out, Amos joined the 19th Regiment, Company A, Wisconsin Infantry on January 6, 1862, as a fifer.

Each company had its own fifer and drummer. It was their duty to signal the troops what to do and when to do it: to march, halt, charge, retreat, fire, etc. They also regulated the camp duty, with a call to dinner, to rise in the morning and call reveille in the evening. They also played during parades, funerals, and for the entertainment of the troops.

Pettis was present for every battle his unit was engaged in, from Suffolk, VA, and New Bern, NC, to the sieges of Richmond and Petersburg.

Amos returned safely from the war in 1865, and became a tailor in Reedsburg.

Amos died July 4, 1880, and is buried in Douglas Cemetery, Marquette County, Wisconsin.

The Call to Arms

The Civil War, The War of the Rebellion, or the War Between the States, began in 1861, and was ostensibly, a fight to free the slaves of southern plantation owners. It divided the union, as well as families, and caused the death of more than 620,000 Americans.

The Call to Arms was raised by Abraham Lincoln, and northern states responded with the enlistment of young men, and old.

Men on horseback rode through Reedsburg shouting, “The War has begun. Troops have attacked Ft. Sumter.” That fateful date was April 12, 1861. At once in the livery stables, barber shops, and across line fences, farmers and shop keepers could talk of nothing else. None of them Irish, German, English, Canadian, Scotch had ever known slavery in their upbringings. The idea that “Slavery is wrong,” had been taught them by their parents. “People should not be owned and worked like oxen and horses.”

All that summer while farmers were shocking oats, cutting hay, and weeding potatoes, the talk continued. Townspeople gathered on street corners discussing the war. “Let's get into this war and free those slaves. It won't take long, maybe a couple of months.”

An article in the 1880 History of Sauk County noted, “The responses to the call were immediate and of the most encouraging character…..No state in the Union was more prompt in sending forward volunteers than was Wisconsin, and no part of Wisconsin responded with greater vigor than did Sauk County.”

Recruiting stations were set up in all the major cities in the county, and men were sent from town to town, looking for volunteers. Again, the 1880 History of Sauk County recounts their travel to Reedsburg: “Arriving at Reedsburg, the Sauk County Rifleman (for such was the name by which these first recruits were known) stopped at the Alba House, where a grand reception awaited them.” Speeches were made by prominent citizens, and ten recruits were enrolled. “The boys returned to their homes to await the call of the Governor, to whom their services had previously been offered.”

That call soon arrived, and the men were ready. These first recruits came primarily from the towns of Reedsburg, Baraboo, Winfield, Woodland and Westfield, and became part of the Nineteenth Regiment, as Company A.

Co. A was organized in Reedsburg in the fall of 1861, with R.M. Strong as captain, Henry A. Tator and Alexander P. Ellenwood as first and second lieutenants, respectively. The company was assigned to the 19th Regiment, then organizing at Racine, and spent the winter there. The men suffered a great deal from the cold, the barracks being far from comfortable. In April, 1862, the regiment went to Camp Randall, Madison, and guarded confederate prisoners until June. Then it was ordered to Virginia, where large forces were gathering for the mighty struggle for Richmond. It is doubtful whether any man in the regiment dreamed at this time that its flag would be the first union flag to float over Richmond, and that that would not occur until almost two years later. The regiment soon reached Norfolk, Virginia, in which city and vicinity it was destined to remain until April, 1863, doing picket guard and provost duty. This duty was performed in a manner that won the praise of the commanding officers, although it was little to the liking of the men. The 19th did more provost duty than any other Wisconsin regiment during the war.

An advance outpost or guard for a large force was called a picket. It was a scattered line of soldiers well in advance of the main army’s encampment, but within support distance. It was considered to be one of the most hazardous duties that an infantry could be assigned, as they were the first to be attacked by the enemy, and more likely to be killed, wounded or captured.

Provosts are military police whose duties are policing solely within the armed forces of a country. It was their mission to administer lawand-order during the Civil War. The provost-marshal, appointed for every military department, partook of the character both of a chief of police and of a magistrate. The Provost obtained guards from the enlisted ranks of primarily infantry and cavalry units as a temporary duty for an as required time period.

The following extract from “Wisconsin In The War,” tells something of the service the regiment was called upon to perform and is interesting, as well in conveying an idea as to what service in the army sometimes called for:

On the 14th of April, 1863, the [Wisconsin] Nineteenth received orders to march without tents to Suffolk to reinforce that place, as an attack was expected from Longstreet’s corps. They marched at ten o’clock in the evening, reached Suffolk at midnight, went two miles farther, through a heavy rain and intense darkness, to the camp of the 21st Connecticut, where about half of the men obtained shelter among the friendly soldiers of that regiment, and the other half suffered exposure to the cold and drenching rain until morning. They had six hundred men for duty. At five in the evening they were ordered to Jericho Creek, where they pitched their tents, which had now been brought forward. At midnight they were ordered under arms, and four companies were directed to march. It was very dark, the roads were bad, and it rained in torrents. The party proceeded seven miles, floundering through the mud as best they could, wading swollen creeks, where one man came near drowning, and immediately entered on picket duty when they reached their destination. One night they spent in the rifle pits on the Nansemood River. Another night one hundred and sixty men, in nine hours, built a corduroy road three hundred yards over a deep marsh, and a rough bridge over a creek ten yards in width, carrying the timber and rails for them on their shoulders from half to threefourths of a mile. At one time half their number, while exposed to a cold rain, had neither rest nor refreshment for thirty-six hours. One night they pitched tents in obedience to orders, and in an hour, by order, struck tents and prepared to march; then, in obedience to new orders, pitched tents again two companies being posted as pickets and at ten o’clock the same night set out on a six miles’ march through deep mud; that accomplished, rested two hours, chiefly in the mud, and then at three o’clock in the morning went into line of battle. That done, they stacked arms, and at daylight engaged in building an earthwork, named “Fort Wisconsin,” here they labored until noon of the next day. Soon after one hundred and fifty men were reported sick; surgeons had resigned; no field officer was with the regiment except Col. Sanders; three line officers were detached from service and four others were sick.

Soon after, this the regiment was sent to Newbern, N.C., and there engaged in outpost duty and participated in a number of minor but sharp fights.

In 1864, the regiment returned to Virginia and engaged in the bloody conflicts before Petersburg and Richmond. At the battle of Fair Oaks, near Richmond, October 27, 1864, a portion of the regiment went into the fight with eight officers and 190 men, and but 44 escaped death, injury or capture.

The flag of the 19th was the first to float over Richmond, when the city fell. Early in the morning of April 3rd , the regiment started hurriedly for Richmond. The men did not know the meaning of the movement. It was simply a question of marching as fast as their legs could carry them. They passed deserted rebel entrenchments and literally ran four or five miles into the city. The flag was run up over the city hall and the regiment was soon hard at work restoring order in the panic stricken and burning city.

Co. A bore an honorable part in the services rendered by the regiment. Captain Strong became colonel of the regiment and H.A. Tator became captain. Failing health compelled him to resign and he was succeeded by A.P. Ellenwood, the Reedsburg schoolmaster who took a number of his pupils to war, including drummer, Frank Pettis.

Young Frank Pettis Heeds the Call

During the Civil War, drummers and buglers were allowed to enlist in the army without meeting the 18-year-old minimum age requirement for a combat soldier. Some estimates noted that 100,000 boys younger than 15 enlisted in the Union Army as musicians. Some 300 were even younger than 13.

It was the duty of the musicians to signal the soldiers when to eat, when to sleep and when to awaken. They also set the pace during marches. During a battle, using their instruments they sounded out to let the soldiers know when to shoot and when to retreat. In the heat of battle, officers shouting orders could not be heard over the din, so the musicians’ louder bugles and drums were used as signal devices.

These young musicians were also required to help remove the wounded from the battlefield, and act as runners or curriers between outposts. They could be required to assist a surgeon in a field hospital holding down a soldier who was having a limb amputated, and then disposing of the severed member.

They were not, however, allowed to carry guns. Instead, they were issued a thin sword, which they wore proudly around their waist. There were occasions, however, when they might be required to pick up a rifle to save their own life, or that of a fellow soldier.

One such youth from Reedsburg, Frank Pettis, was eleven years old when he enlisted in the Union Armyas a drummer boy, on January 7, 1862. His father, Amos, played the fife and had enlisted about the same time.

Several months later, on February 22, 1862, at the age of 12, Frank began his military service with his teacher, Captain A. P. Ellinwood, and his father, in Wisconsin’s 19th Infantry, Company A.

Pettis was present at every battle the 19th unit fought from Suffolk, VA, and New Bern, NC, to the sieges of Petersburg and Richmond, where the colors of his regiment were the first to fly from the Confederate capital building in Richmond, VA. There is an abundance of information on the unit’s sojourn at New Bern, NC, so I shall concentrate the balance of this story on that location.

Soldering In North Carolina

By Private Thomas Kirwan Massachusetts 17th Regiment, Company K

Late summer of 1862…This excerpt contains a description of what the New Bern, Evan’s Mill encampment would have looked like when Frank Pettis’ unit was stationed there later in 1864.

About a mile further on, after passing through a narrow belt of woods, we came out upon Evan’s plantation. On our right was a field of some eighty acres, about half of which was covered with a young growth of apple trees. On the left was a field of about twenty acres, at the further end of which was the plantation house, with its Negro huts, surrounded with the inevitable grove of elegant shade trees. Just opposite the front gate of the mansion, the road turned sharp to the right, and on looking ahead, we beheld a blockhouse, nearly completed, in the rear of which was the encampment, and our future abode. Upon reaching the block-house, the road took a turn to the left, down a short, steep hill, skirting the bank of a stream, which it crossed on a rude plank bridge, still turning toward the left.

After crossing the bridge, a grist mill lay on the right, and about 69 yards on the left, on the dam of a magnificent pond of water stood a large saw mill, which ran two sets of saws when in operation. It was then idle, the dam having broke away. The road, after crossing the flume of the grist mill led on to the Negro village--quite a collection of comfortable houses built on each side of the cross road, which led to Pollocksville. Just before coming on to the Pollocksville road, in a field to the right was a large cotton gin and press. At the intersection of these roads was our outpost in the day time, the guard being drawn in to the mills at night.

On entering the front gate, I was struck with the size and beauty of an immense beech tree, whose wide extending branches covered a circle of over 190 feet in diameter and in Yankee fashion, I immediately computed that if cut down it would make over five cords of firewood. It must have proved a cool and inviting shade for the planter and his family in the summer time.

Approaching its huge trunk, I observed that the Yankee jackknife had been at work and covered it with the representative names of men from nearly every United States regiment that had ever been in the department. Besides the huge beech there were numerous other trees elm, cedar, cheney and the beautiful flowering althea.

The house was an ordinary two story one, containing about 7 rooms, set on brick blocks about three feet from the ground, and serving as a cool place of resort for the pigs, fowl, and youthful, curly-headed Negroes, during the heat of the day. This, together with the plantation attached of some 10,000 acres, seven or eight hundred of which were cleared, together with the mills…

At the back of the mansion house were two Negro huts, where those who were domestics were lodged. The body of the Negroes were lodged as mentioned about a mile away.

Adjoining the Negro-huts attached to the mansion were the various outhouses and stables, behind which the land sloped to waters of the tortuous stream which emptied into the mill-pond further down. To my view Evan’s Mills at first appeared a lonely place; but a further acquaintance with it materially altered my opinion. Were it not that the restraints which discipline imposes upon the soldier, living in this place would be quite agreeable.

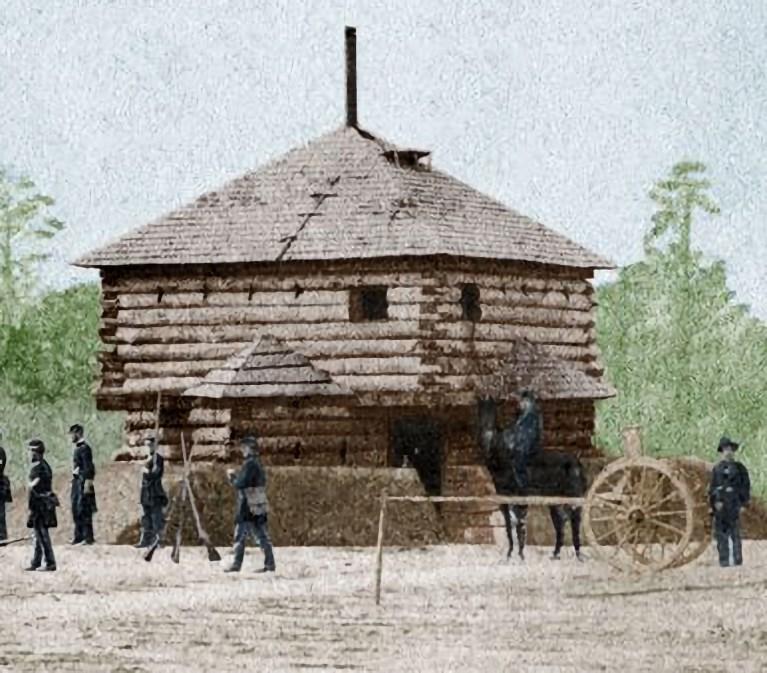

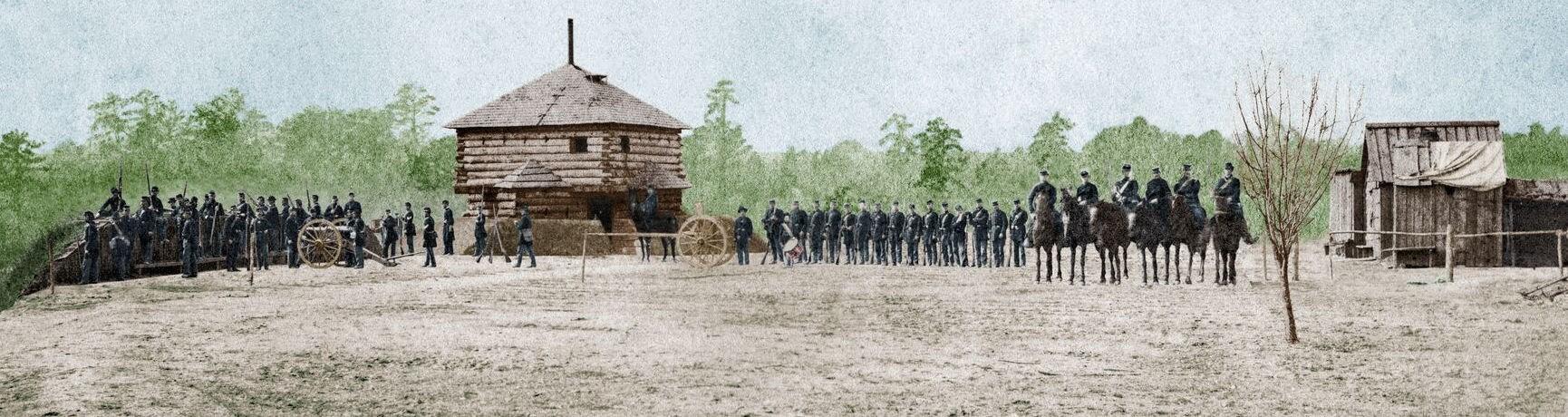

In 2016, the Sauk County Historical Society received an e-mail from a gentleman in New Bern, North Carolina, Steve Dembickie, who had seen a photo on our Society’s web site which matched one that he had in his collection. It depicted a blockhouse, which, during the Civil War, existed near where his home is located today. This blockhouse was a temporary location for Wisconsin’s Company A, 19th Infantry encampment during the war, the company in which Frank Pettis was serving. The photo shows soldiers lined up, possibly for an inspection, and right in the center, is a little drummer boy! [Click here for image]. None of the soldiers were identified, but it seems logi-cal that the boy would have been Frank.

Frank Pettis, Drummer

Additional information on the 19th Wisconsin Infantry, was found in Merton Krug’s 1929, History of Reedsburg and the Upper Baraboo Valley. Krug wrote that, “At the confluence of the Neuse and Trent rivers near New Bern, on Brice Creek a location that the rebels considered an important outpost and which they had strongly fortified had been “wrested from their hands by the bravery of the Union troops.

“It was here that Wisconsin’s 19th Regiment was assigned to provide picket duty at Evan’s Mill on Brice Creek. It was a swampy area with only one accessible route. “At that place was a saw and flourmill and a large plantation which had belonged to General Evans of the rebel army,” wrote Krug. Officers were quartered in the mansion, with the soldiers residing in a barracks built for the purpose. A photo in the Reedsburg Old Settlers’ collection, depicts a man on the porch, with a boy seated on his lap. Upon closer inspection, the boy is wearing a uniform exactly like the one in a tintype of young Frank Pettis! Since Frank’s uniform is unique, it has to be him. See photo below.

“At the time of the attack upon Newburn (sic) on February 1, 1864, Company A was also attacked by a brigade of rebel cavalry and a battery of artillery. They sent to New Bern for reinforcements and received three companies of cavalry and a twelve pound howitzer with men to man it.” noted Krug. They were able to hold out for three days.

Wisconsin 19th, Company A, Headquarters at New Bern, NC, 1864. Frank Pettis is seated on the lap of another soldier, Lewis H. Cahoon, on the far left on the porch in the above photo. An enlargement of that area is shown on the left. Also see photo on page 40.

Orders were then received from headquarters at New Bern, for the 19th to fall back to that city. The rebels had found a way around the swamp and were about to recapture the place where Pettis and his unit were camped. This forewarning saved the regiment from ultimate capture. Shortly thereafter, the rebels abandoned the location and the 19th regained the position. They rebuilt what the rebels had burned, and remained there until April, 1864.

Union Battle Reports

These reports were made on the days that Evans Mills was being attacked when the Wisconsin 19th, Co. A was garrisoned there. Brigadier General, I. N. Palmer, Commanding General of the New Bern District, sent the following reports.

New Berne, February 2, 1864 5:15 p.m.

MAJOR: I am justified informing by telegraph that the post of Newport is attached, and I think it will fall. The rebels have the railroad now between Newport and Morehead City. The post at Evins’ Mill is also surrounded, and our little forces at these points will no doubt be defeated, as the opposing numbers are much the largest……….

New Berne, N.C., February 3, 1864 8 p.m.

MAJOR: M y last communication to you concerning the state of affairs at this place was addressed to you yesterday at 5 p.m. At that hour the communication with Morehead City by telegraph was interrupted, and the telegraph operator at Newport reported the rebels on the railroad at that place. I was in communication with the stations Croatan and Havelock until 10 p.m. yesterday, at which time I ordered the commands at those points to this place, as the post at Evans’ Mill was about to be attacked; and, if carried, the commands at the stations mentioned would have been jeopardized. The commands came safely. At midnight the rebel force under the immediate command of General Pickett, commenced to retire toward Kinston……..

The Civil War Blockhouse

The blockhouse was built of hewn logs and usually consisted of two stories. [Click here for image]. Some of the troops would have their barracks there in the blockhouse, while others would be in their tents or out buildings. It would be supported by one heavy gun mounted at an elevated point, so as to allow the small garrison to keep a large force at bay. There would also be a redoubt (trenches) dug around the perimeter of the blockhouse. Units would communicate back and forth during battles using couriers to forward communiques, and they also were using the telegraph quite a bit as well as the signal corps (flags).

Evans Mills [North Carolina]

1863: Gustavus B. Williams to Bernette (Hill) Williams

These letters were written by Sgt. Gustavus B. Williams of Co. K, 51st Massachusetts Infantry a 9-months enlistment organization.

The sergeants and privates have quarters in board huts accommodating from two to a dozen or more each, and the block house — a strong log building of two stories with port holes for cannon and perforations for musketry.

Our mail will be promptly brought us. We have a mule and cart and the Captain has a horse, one of which will go almost daily to the city about eight miles distant. This was an immense plantation with two hundred (I judge) negroes upon it. A creek flowing near us carries a sawmill and a grist mill. A plantation sergeant has charge of the whole and last year raised considerable produce. The mills are kept running now and the Government have agents manufacturing tar a mile below here. Tar is worth at the North, I have heard, about $40 per barrel. A great many contrabands I don’t know how many — are employed here so you see we have in our care much that is valuable. Game and fish abound. Eggs at 25 cts a dozen can be bought and milk at 10 cts so we need not starve. I had milk in my tea last night a great treat, and if my box with butter and cheese comes as I expect by next steamer, I shall live well.

The ground is elevated and the place must be healthy at least till hot weather comes. The spring comes on very slowly though oats are up already looking quite good. There was a hard frost last night and winter clothing is very comfortable yet.

In the creek and swamps we are told are [Water] Moccasins, Copperheads, Rattlesnakes, alligators, wood ticks, and what besides of danger, we don’t know nor wish to know. Our huts have an abundance of rats. We do know but we can guard against them only keep the Rebs away.

Lieut. Coleman was at Newbern when the pictures were taken. I shall buy the two described…the photographs were taken March 28. I shall…send them when they are finished. The samples are now before me hence I describe them so that you will know what they mean if you get them. The ground slopes abruptly from the block-house towards the angle of the river which is bridged. The bridge is commanded by the six pounder cannon. The stream…in front of the spectator flows through swamps apparently impassable. The enemy must approach by the road…they would stop on the distant plains and shell us out rather than attack with cavalry or infantry by the flank being up on two bridges, one already mentioned the other just beyond across the mill trench…both under our guns…

The following description of the events at New Bern is taken from the “History of Reedsburg and the Upper Baraboo Valley” by Merton Edwin Krug, 1929.

NEWBURN, N. C.

At this place they [Wisconsin 19th, Co. A] landed on the eleventh. This is one of the finest towns in the state, containing about five thousand inhabitants and situated at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent rivers. The rebels considered it an important position and had strongly fortified it early in the war. It was wrested from their hands by the bravery of the Union troops under Generals Burnside and Commodore Goldsborough in February, 1862.

Upon the arrival of the regiment in Newburn, Company A was assigned to outpost and picket duty at Evans’ Mill on Brice Creek, eight miles south of the city. At that place was a saw and flourmill and a large plantation which had belonged to General Evans of the rebel army. The officers were quartered in the Evans mansion, and the soldiers in barracks erected for the purpose. From west and south there was but one place of access, on account of intervening swamps, and that was across the milldam, and, this enabled the company to hold the position against superior numbers of the enemy.

At the time of the attack upon Newburn on the first of February, 1864, Company A was also attacked by a brigade of cavalry and a battery of artillery. They sent to Newburn for reinforcements and received three companies of cavalry and a twelve pound howitzer with men to man it. With this assistance they held the rebels in check three days. Captain Tator who was in command of the outpost and who was an efficient officer, sent out cavalry scouts several times a day to watch the enemy and ascertain their position and what they were doing. At one time they found them building a bridge, evidently for the purpose of bringing over their artillery for an attack; but a severe shelling from the howitzer stopped the enterprise. It is probable that the manifest boldness and daring of the Union troops led the enemy to the conclusion that the force at the outpost was superior to what it was in fact.

On the morning of February 3rd, Captain Tator received orders from General Palmer, commanding at Newburn, to fall back to the city, soon after which, the rebels, guided by a Sesesh [Secessionist] planter named Wood residing in the neighborhood marched around the swamp on the south and coming in on the rear, took possession of the place. Company A was thus fortunately saved from being taken prisoner.

Upon their evacuation of the place, they burned the barracks and other property which they could not take. The rebels destroyed other property, and undertook to burn the Evans mansion but the fire was extinguished before much damage was done.

The confederates soon abandoned the position and Company A was reinstated. In rebuilding their barrack they tore down some buildings formerly used as slave cabins. In one of them was found an old rebel payroll, on which the name of Wood as a recruiting officer appeared, whereupon Lieutenant Ellinwood and a small detail of men went out to his plantation and brought him in as prisoner. He was sent to Newburn and thence delivered to the tender mercies of General Butler, commandant at Fortress Monroe, who ordered him into confinement at the ripraps.

In the latter part of April, 1864, the regiment was ordered to Yorktown, where a week was spent in reorganizing the army. Company A was placed under the command of Captain Tator.

The Wisconsin 19th, Company A, went on to fight many other battles with bravery and fortitude.

When Frank Pettis’ enlistment was up after 3 years as a drummer boy, he could have called it quits and returned home. However, at the age of 14 he reenlisted as a regular soldier and stayed the course of the war. His father, Amos, after having served his three years, was mustered out on February 22, 1865. Frank and his teacher, Ellenwood, returned home safely after the war, and were mustered out on August 9, 1865.

The 19th Co. A Wisconsin suffered 2 officers and 41 enlisted men killed in action or who later died of their wounds, plus another 3 officers and 115 enlisted men who died of disease, for a total of 161 fatalities.

The 19th Regiment, Co. A of which was raised in this county, arrived at Madison yesterday, to be mustered out. A reception was given it jointly with the 33rd Regiment, which arrived there at the same time. The 19th, it will be remembered, claims the honor of being the first regiment that unfurled the flag of the Union in the rebel capital upon its evacuation by Lee. February, 1865

Regimental History of the Wisconsin 19th Infantry

Nineteenth Infantry. Cols., Horace T. Sanders, Samuel K. Vaughn; Lieut. -Co1s., Charles ‘Whipple, Rollin M. Strong, Majors, Alvin E. Bovay, Amos O. Rawley. This regiment was organized in the winter of 1861-62, at Camp Utley, Racine, and was ordered to Camp Randall on April 20 to guard Confederate prisoners sent from Fort Donelson. It was mustered in April 30, 1862, left the state June 2, and was on garrison duty at Norfolk, Va., until April 14, 1863. It was then on picket and guard duty at various points for about two weeks, when it was assigned to duty at West Point and Yorktown until the middle of August, and at Newport News until Oct. 8. It was then divided by companies for outpost and picket duty at points near New Berne, N. C, and was in several small engagements with the enemy. It was ordered to Yorktown, April 28, 1864, and on May 12 the right wing, acting as a skirmish line, covered the 3d brigade. It accompanied the general advance upon Fort Darling, carried the first line of the enemy's works, and occupied the road in the rear of Fort Jackson, where the next day the regiment was united. It was compelled to fall back by the furious assault of a heavy force, but it did so in good order. It took part in the operations about Petersburg, doing siege and picket duty in the trenches. In August the veterans were sent home on furlough but returned in October, and participated in the engagement at Fair Oaks, a force of less than 200 men being engaged and suffering a loss of 136 wounded and captured. They were joined by the non-veterans and the regiment was kept on picket duty in front of Richmond until April 3, 1865, when it entered the city and planted the regimental colors upon the city hall. It was on provost duty at Richmond, Fredericksburg and Warrenton until Aug. 4, and was mustered out at Richmond Aug. 9, 1865. Its original strength was 973. Gain by recruits, 187; substitutes, 54; veteran reenlistments, 270; total, 1,484. Loss by death, 136; desertion, 46; transfer, 152; discharge, 345; mustered out, 805.

From “The Union Army”, by Federal Publishing Company, 1908, Volume 4.